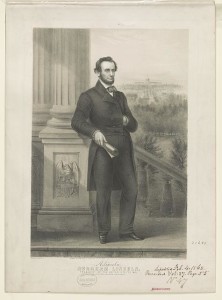

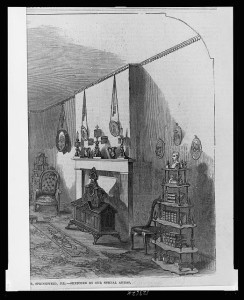

can’t go home again? Lincolns’ parlor in Springfield (Frank Leslie’s 1861)

150 years ago today a “mass meeting of unconditional Union men” was held in Springfield, Illinois. President Lincoln had been invited to speak at his pre-presidency hometown but couldn’t leave Washington “because Rosecrans had finally begun his long-awaited campaign to maneuver the Confederates out of Chattanooga[]” Instead he sent a letter for his friend, James C. Conkling, to read at the meeting. One of the big issues the letter addressed was the difference of opinion between pro-Unionists on the issue of emancipation. Even in upstate New York some soldiers admitted they would give their all to save the Union but not to free slaves. Here’s a bit of Mr. Lincoln’s response:

But, to be plain: You are dissatisfied with me about the negro. Quite likely there is a difference of opinion between you and myself upon that subject. I certainly wish that all men could be free, while you, I suppose, do not. Yet, I have neither adopted nor proposed any measure which is not consistent with even your view, provided you are for the Union. I suggested compensated emancipation; to which you replied you wished not to be taxed to buy negroes. But I had not asked you to be taxed to buy negroes, except in such way as to save you from greater taxation to save the Union exclusively by other means.

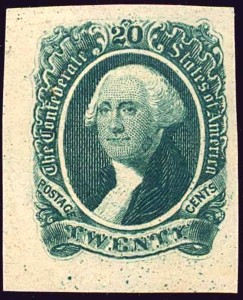

You dislike the Emancipation Proclamation, and perhaps would have it retracted. You say it is unconstitutional. I think differently. I think the Constitution invests its commander-in-chief with the law of war in time of war. The most that can be said, if so much, is, that slaves are property. Is there, has there ever been, any question that by the law of war, property, both of enemies and friends, may be taken when needed? And is it not needed whenever it helps us and hurts the enemy? Armies, the world over, destroy enemies’ property when they cannot use it, and even destroy their own to keep it from the enemy. Civilized belligerents do all in their power to help themselves or hurt the enemy, except a few things regarded as barbarous or cruel. Among the exceptions are the massacre of vanquished foes and non-combatants, male and female.

The letter was “[r]eceived ‘with the greatest enthusiasm’ by the 50,000 to 75,000 cheering Unionists who attended the Springfield rally …” A Democrat newspaper labeled it the first speech in the president’s re-election campaign. Republicans loved it, and it was re-read to a mass rally in New York City.[]

The New-York Times of September 7, 1863 praised the president, his principles, and his communication skills – and likened Mr. Lincoln to George Washington:

The Right Man in the Right Place.

The President’s letter to the Springfield Convention receives the unqualified admiration of loyal men throughout the breadth of the land. Various as have been their sentiments on some of its topics, it is yet their universal testimony that nothing could have been more true or more apt. Its bard sense, its sharp outlines, its noble temper, defy malice. Even the Copperhead gnaws upon it as vainly as did the viper upon the file.

Men talk about a courtly felicity of speech, and term it a rare accomplishment. So indeed it is. Nothing but high culture and the most patient practice confers it. Here is a felicity of speech far surpassing it, yet decidedly uncourtly. The most consummate rhetorician never used language more pat to the purpose; and still there is not a word in the letter not familiar to the plainest plowman. But what is still better than even felicity of expression, is felicity of thought. Not only the President’s language is the aptest expression of his ideas, but there is a similar fitness of his ideas to the occasion. He has a singular faculty of discovering the real relations of things, and shaping his thoughts strictly upon them, without external bias. In his own independent, and perhaps we might say very peculiar, way, he invariably gets at the needed truth of the time. When he writes, it is always said that “he hits the nail upon the head,” and so he does; but the beauty of it is that the nail which he hits is sure to be the very nail of all others which needs driving. …

Lord BROUGHAM remarked of WASHINGTON that “the human fancy could not have created a combination of qualities more perfectly fitted for the scenes in which it was his lot to bear a part.” This same consummate fitness for the times may be recognized in the man at the head of the affairs of the country in this second great crisis of its existence. Rather we should say is recognized; for it is certain that, in spite of all the hard trials and the hard words to which he has been exposed, ABRAHAM LINCOLN is to-day the most popular man in the Republic. All the denunciations and all the arts of demagogues are perfectly powerless to wean the people from their faith in him. There is a general conviction that he is just the man for the occasion. And it is a conviction that is constantly growing clearer and deeper. The more experience the country has of President LINCOLN, the more he obtains its confidence.

It would be hard to think of two men more unlike in some of their characteristics than the first President and our present one. Yet, in general cast of mind and heart, the latter probably more nearly resembles WASHINGTON than any of his predecessors. Without anything like brilliancy of genius, without any very great breadth of information, or literary accomplishment, or inventive power, he still has that perfect balance of thoroughly sound faculties which gives an almost infallibly sure judgment. This, combined with great calmness of temper, great firmness of purpose, supreme moral principle, and intense patriotism, makes up just that character which fits him, as the same qualities fitted WASHINGTON, for a wise and safe administration of affairs in the season of great peril.

It is almost fearful to contemplate what might have been the consequences had we an Executive of different mould. We have had Presidents of a headstrong temper, who, when hard pressed, would listen to no counsel, but rush on self-willed; others of a feebleness of spirit that made them the mere playthings of circumstances, or the passive tools of other men’s arts. We have had Presidents who would have found it almost impossible, in any exigency, to rise above a party level; others who, though they might detach themselves from party, would do so only to seek the swift popular current that should bear them on to a second term. Had we a man now at the head of affairs belonging to any of these classes, the national ruin would be almost inevitable. There could have been hardly a hope of escaping wreck, in this dreadful storm, under such pilotage. The very knowledge that we had so unreliable a hand at the helm would have almost paralyzed effort. There would have been no such collected energy as we have seen, no such steady confidence in the great popular heart. All would have been uncertainty, dissension and confusion. We have had many reasons to be thankful to heaven for its orderings in aid of our rightly acquitting ourselves toward this wicked rebellion; but for no one thing have we so great cause for gratitude as for the possession of a ruler who is so peculiarly adapted to the needs of the time as clear-headed, dispassionate, discreet, steadfast, honest ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

![Co. H, 10th Veteran Reserve Corps, Washington, D.C. April, 1865 (photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: C-DIG-ppmsca-34765)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/34765r-300x198.jpg)

![Band of 10th Veteran Reserve Corps, Washington, D.C., April, 1865 ( photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34764)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/34764r-300x211.jpg)

![Lincoln quick step (Phila. : T[homas] Sinclair's Lith., 1860.; LOC: LC-USZ62-89291)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/3b35669r-228x300.jpg)