If this war ever ends, I’m going to miss the rhetoric in the Richmond Dispatch. I’m certain … I’m pretty sure sometime in the last three years I’ve read an editorial that maintained Northern Democrats were bigger threats to the South than Black Republicans. The occasion for this editorial, however, was the approaching Democrat convention that would nominate a U.S. presidential candidate and a pronouncement from a Democrat relic, who comes across as a bit of a Rip Van Winkle who after four years woke up to the fact that South really was seceding. This editorial claimed that if Democrat officers and men didn’t volunteer for the Union army, the Northern war effort didn’t stand a chance; Peace Democrats were a bigger threat than Abolition Republicans because they thought that with sweet words everything could be restored to the status quo ante, while ignoring the mayhem the federal military caused throughout the South. The Confederacy would rather fight Abraham Lincoln, who is useful as a combination George III and Pharaoh, whose policies are so destructive that the South will never submit.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch January 25, 1864:

The Northern Democracy again.

On the 4th of July, the anniversary of the Declaration of their Independence by the Rebels of ’76, the National Democratic Convention of the United States meets at Chicago, to nominate a candidate for the Presidency. A Congressional Democratic caucus, which lately assembled at Washington, has adopted resolutions disapproving of Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation, and also declaring in favor of such a policy to wards the people of the insurgent States, as is best calculated to bring the war to a close and restore said States to the Union, under the Constitution, with all their constitutional rights unimpaired. It is also announced that the greatest harmony prevails between Democrats and Conservatives.

‘Methuselah’ thinks South might actually want to break free

This intelligence is not without interest in the Southern Confederacy. Amos Kendall, who lately presided over a conservative meeting in Philadelphia, gravely announced that a suspicion had recently sprung up in his mind that the Confederates really intended to dissolve the Union! We frankly confess that an idea of the same sort has more than once occurred to us since the first blood was shed at Bethel. We have not been able to dismiss the apprehension that permanent alienation of feeling might spring up from the constant bickering of Yankees and Confederates for the last three years. Perhaps it is owing to a despondent temperament, or a natural propensity to looking on the dark side; but, so it is, we have some times found that the constant recurrence of such unfraternal broils as those at Manassas, on the Peninsula, in Northern Virginia, it Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and every other Southern State, might lead ultimately to a separation and dispersion of the whole happy American family. We have at times fancied that we heard the rattle of musketry, the roar of cannon, the groans of the wounded, the sorrowful sighing of captives; that we have seen the pale faces of dead men, the tearful eyes of widows, and whole districts of country, once the garden spots of the earth, changed into a howling wilderness.–We have even dreamed of millions of men being in arms, of a despot at Washington filling dungeons with prisoners; of Southern soldiers tortured and hung; of great battle fields, where twenty or thirty thousand fallen warriors slept their last sleep on earth. All this must have been a dream, engendered by the excited state of the public mind for the last three years, and the crimination and recriminations which have passed between estranged and unnatural brethren. A like effect seems to have been produced upon the venerable Kendall, (now we should think about the age of Methuselah,) and the apparition has been so much like daylight life that he begins, like ourselves, to fear that he is awake, and that all this is not an oppressive nightmare, but a horrid reality.

The National Democrats of the United States have not yet arrived at the sombre and intelligent apprehensions of the melancholy Kendall. They appear to indulge sanguine hopes of the probability of averting that dismal catastrophe, the dissolution of the Union, by such a policy towards the insurgent States as will bring them back in love and confidence to the dear old family hearthstone. They evidently look upon the visions which more or less have visited all men’s minds, of blood, slaughter, desolation, groans, and wailing, as mere phantasmagoria, illusions of the eye and ear — possibly, even forerunners of coming insanity, which may, however, be averted by a judicious course of treatment. They therefore propose a certain “policy,” a “policy”–lovely word, suggestive of everything honest, candid, and above-board — which will soothe and harmonize all conflicting elements and dismiss from the body politic forever those distempered dreams which are now haunting its imagination. They will open the eyes of the wretched sleepers, and enable them to wake up and thank God that all this has been a dream. The mothers, wives, and sisters whose faces are wet with bitter tears, will wake to find their loved ones once more in their warm embrace; the aged father will grasp once more to his heart the manly son who was his pride and hope, and whom in a dream of agony he had seen mangled and dead upon a furious battle field; the captain who had fancied himself in a dismal cell, pining away his life in a hopeless captivity, will wake to breathe once more upon his native sod the free air of heaven. The dry bones of the vision will stand up an exceeding great army, rising from their multitudinous graves as it the last trumpet had sounded, and bearing aloft the celestial banner of the Stars and Stripes. Davis and Lincoln will rush into each other’s loving arms, the inevitable negro will once more return to his appropriate sphere, and — the Democracy will divide the spoils.

the devil the South knows

To dismiss these blissful visions, and come to sober, waking truth, we must say in all sincerity that we regard the Northern Democracy and their “policy” as the worst form of Northern hostility which has been manifested in the war. But for them we should not be where we now are. But for the military chieftains and soldiers of Northern Democracy, who once professed to be the bitter enemies of coercion in every shape and form, the war could not have lasted two months. The Black Republicans proper, unaided by the Democratic element, would have been struck with paralysis before Lincoln had been three months in his seat. At the same time, however, that this “politic” party has given the war its chief impetus in leaders and men, it has professed a policy of peace upon honorable terms, which was far more formidable in its arts than the combined arms of all parties at the North.–There was at one period of the war more danger from its seductive tongue than the brawling and bitter months of Lincoln and his Cabinet. Even now, we would much rather have Lincoln for the President of the United States than the candidate of the Conservative Democracy. Lincoln seems to have been raised up, as was George the Third, to render a restoration of Colonies to their tyrants impossible. If he had pursued the wise and conciliatory measures which the Northern Democracy profess to advocate, “the rebellion” would have been peacefully smothered in its cradle. But his heart has been hardened, like Pharaoh’s; he has gone from bad to worse; he has so trampled upon all law, disregarded all right, and outraged all humanity, that the whole Confederacy has become consolidated in the resolute determination to submit to every form of human suffering rather than return to the detestable embrace of a Government which he has rendered to their minds an embodiment of the Powers of Darkness. So long as he is President, so long as we see the Devil in his proper shape and form, we have nothing to fear; we have only to resist the fiend, and he will flee from us. It is only when the Prince of the infernal regions takes the shape of an angel of light that the faithful are in danger. We must be excused therefore, from wishing success to the Northern Democracy. Let the North stick to its representative man, and not change front in the hour of battle.

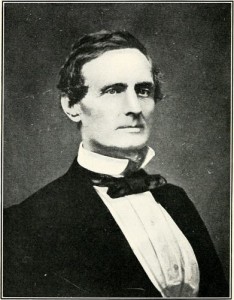

Amos Kendall (1789-1869) was an influential journalist and Democrat. After Andrew Jackson was elected in 1828:

In 1829, Kendall was appointed fourth auditor of the United States Department of the Treasury. The following year, Jackson supporters won control of the Washington Globe newspaper in Washington, D.C. The newspaper became the house organ of the Jackson administration, and Kendall brought Jackson’s nephew, Francis Preston Blair, to Washington to be the paper’s editor-in-chief. Along with Duff Green, Isaac Hill, and William Berkeley Lewis, Kendall was a member of Jackson’s Kitchen Cabinet. Over time, Kendall came to dominate the Kitchen Cabinet. He had more influence over Jackson than any other Cabinet official or Kitchen Cabinet member. Kendall took many of Jackson’s ideas about government and national policy and refashioned them into highly polished, erudite official government statements and newspaper articles. These were then published in the Globe and other newspapers, enhancing Jackson’s reputation as an intellectual. Kendall also drafted most of Jackson’s five annual messages to Congress, and his statement vetoing the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States in 1836. [well footnoted at Wikipedia]

Mr. Kendall served at 8th U.S. Postmaster General from 1835-1840. Depending on your definition of friend, he showed himself a friend of the South: “Despite having no legal basis for his action, he also allowed postal officials in the Deep South to refuse to deliver abolitionist literature.”

![Confederate artillery near Charleston, S.C. in 1861 [i.e. 1863] (by George Smith Cook, photographed 1863, printed between 1880 and 1889; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-35428)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/35428r.jpg)

![[Unidentified soldier in Confederate uniform with bouquet of flowers] (between 1861 and 1865; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-33309)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/33309r-254x300.jpg)

![[Private Richard F. Bernard of Co. A, 13th Virginia Infantry Regiment, in uniform] (between 1861 and 1864; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34336)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/34336r-267x300.jpg)