On February 1, 1864 President Lincoln ordered a draft of 500,000 men. Democrat papers in upstate New York examined the president’s words to try to figure out how many previous enrollees might be credited toward the new call. I’m about a week late on at least one of the following two articles.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in February 1864:

The Call for 500,000 Men.

The call of the President for 500,000 more men has taken the country by surprise. It was generally believed that the country was furnishing the administration all the men it required under the call of October last. But it seems not; and the following order was issued on Monday last:

WASHINGTON, Feb 1. – Ordered, That a draft of five hundred thousand (500,000) men, to serve for three years or during the war, be made on the tenth (10th) day of March next, for the military service of the United States, crediting and deducting therefrom so many as may have been enlisted or drafted into the service prior to the first (1st) day of March, and not before credited.

(Signed) ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

The Administration journals construe the meaning of the above somewhat differently. Some assert that it includes the 300,000 called for in October last, while others insist that its language will not admit of such construction, and that is an order for 500,000 additional men. The Administration may possibly vouchsafe an explanation in due time, in order to quiet the agitated public mind. In the meantime it is expected that everybody will rush to arms to aid on the work of war, desolation and plunder, and if need be to lend a helping hand to perpetuate the reign of the present corrupt and profligate dynasty.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in February 1864:

The War Calls.

There is some difference of opinion as to the aggregate of the calls for troops, but the fact of the calls is correctly set down as follows, year and date being given:

April 16, 1861 …………………………. 75,000

May 4, 1861 ……………………………. 64,748

From July to December, 1861 … 500,000

July 1, 1862 ………………………….. 300,000

Draft summer of 1863 ……………. 300,000

February 1, 1864 ………………….. 500,000

Total ………………………………….. 2,039,748

This is the aggregate of the calls for men in the army alone, while the naval service foots up as follows, as shown by the recent report of the Secretary of the Navy:

Vessels in service and building … 588

Total tonnage …………………. 498,000

No. of guns ………………………… 4,443

No. of seaman July 1st ……… 34,000

It seems almost incredulous that so many men have been called into the service since the outbreak of this most unnatural strife. The demands of the Administration so far have been promptly met, but the time is rapidly coming when the patience of the country will have become exhausted. It cannot be that this people will much longer quietly submit to the terrible sacrifices that the Administration continually demands. The end is surely coming!

I’d say The New-York Times, which actually published the president’s February 1st order on February 1st, was basically a pro-Administration journal. It construed the president’s words to mean an enlargement of the last draft. Later on it hinted at one of conscription’s main purposes – to encourage volunteers[]. From The New-York Times February 2, 1864:

The New Draft a Wise Measure.

The public mind has been flattering itself that the fighting period was nearly over, and was little prepared for the President’s enlargement of the last draft from three hundred thousand to five hundred thousand. At first look the new burden is not an agreeable one; yet every man who desires a speedy termination of the war, ought to welcome it. It is the one great requisite for that end.

The great mistake from the beginning of this war has been the failure to put adequate forces into the field. There is no reason why three or even five such armies as the Army of the Potomac should not have been operating against the enemy at the close of the first year of the war. A million and a half of men could have been drawn from the country with less effort than has since been expended in keeping up the number of effective soldiers to a third of that figure. Properly equipped and disciplined, and simultaneously hurled, forward upon the “Confederacy” from different directions, they would have crushed it within six months, almost to a dead certainty. It would not have been within the power of the rebel leaders — whatever their civil energy or their military skill — to withstand such a combination of great movements. But this grand levy was not made. The consequence is that the minor levies have had to be and will have to be repeated to such an extent that the final aggregate will amount at least to the million and a half before the war closes, while the destruction of life and the accumulation of debt will be double what they otherwise would have been.

We don’t say this as complaining of the Government. To understand after experience is easy for all. To understand before experience is sometimes impossible even for the wisest. The mistake was universal — indulged not a whit less by the people than by the Government. It sprang from an inadequate comprehension of the spirit and resources of the rebellion. Nobody believed that the Southern people could be brought up to such desperate resistance, or that the rebel chiefs could find the means, even if they found the men, to maintain the war on so mighty a scale. …

But, even as it is, a great effort must be put forth to supply the Government with the number it demands. All loyal men must firmly nerve themselves to meet the call. They must make the best use of the present month to supply the quotas, as far as possible, by promoting volunteering; and, when the draft comes, they must sustain the Government in enforcing it with most thorough rigor. Faction will again do its utmost to make trouble. It must be kept under by public opinion in its sternest exercise. The Enrollment Law has been, or will be amended, so as as to remove all its old inequalities and defects, and in all essential respects will be as just and efficient as any human legislation on the subject can be. Congress is discharging its whole duty in perfecting it. The President is discharging his whole duty in applying it. It remains for the people to discharge their whole duty by sustaining it. Congress may devise ever so effective machinery; the Executive may put it on the track ever so promptly and squarely; and yet, without the motive power of the popular will, it can accomplish nothing.

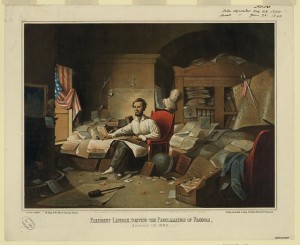

![[Lincoln & Douglas in a presidential footrace]. No. 1, 1860 ( Buffalo, N.Y. : Published by J. Sage & Sons, 1860; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-15777)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/3a17091r-300x245.jpg)