Here’s another one paragraph letter from H.B. Compson, a young Cavalry officer, describing “one of the greatest raids of the war”, in which Compson and others lost their horses as they covered a ‘retrograde movement’ and had to make their way on foot through rebel territory to get back to the Union lines.

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in 1864:

Letter from the 8th N.Y. Cavalry.

CAMP 8th N.Y. Cavalry,

NEAR LIGHT HOUSE POINT, VA.,

July 8th, 1864.

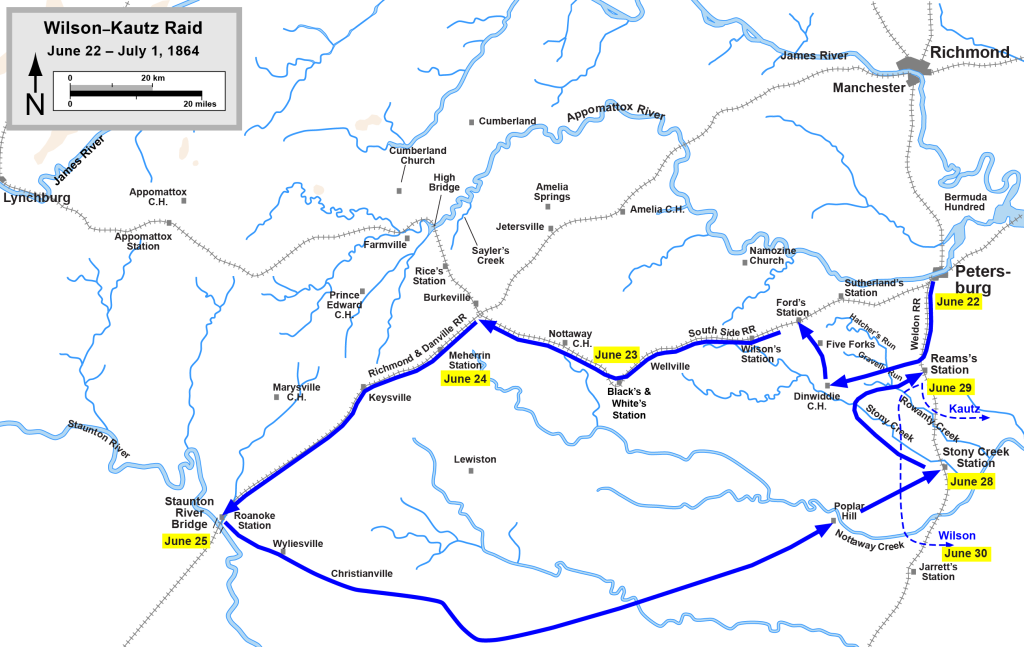

We have just returned from another great raid made by the 3d Division commanded by Gen. Wilson. I can safely say that it is one of the greatest raids of the war. We have accomplished more in the destruction of property to the Confederate States than has been done by any raiding party since the breaking out of the present war. I will now mention a few important places that we passed through, and by referring to a war map you can at once determine our course. On the morning of the 22d of June, we took up our line of march from Prince George Court House, crossing the Norfolk and Petersburg R.R., thence to Petersburg and Weldon R.R. crossing it at Reames’ Station. Here we met a small force of the enemy who after firing a few shots fled. We burned the Station and destroyed the track for several miles, cut the telegraph wires, and then proceeded to the Lynchburg and Petersburg R.R., struck it at Fords Station, captured and destroyed two train [sic] of cars and burned the Station. Our attention was then turned to the road, which we completely destroyed to Black and White Station, a distance of about twenty miles. Here we met a Division of the enemy’s Cavalry, and a desperate fight ensued, which lasted several hours; holding our ground and sustaining a loss of eight killed, twenty-four wounded and seven missing. From this point we marched to the Richmond and Dansville R.R./ striking it at Manerin [Meherrin] Station. One Brigade proceeded to Berksville Junction, destroyed it after accomplishing its objective. – The whole command proceeded down the railroad, completely destroying everything as far as the Staunton river, where we again met the enemy. Having accomplished our object, we commenced the retrograde movement to gain our lines. We heard the enemy’s Cavalry and Infantry were waiting for our return. On the evening of the 28th of June, we arrived at Strong Creek Station where we found the enemy as we had heard posted in force. We at once engaged them but found them to [sic] strongly posted to be driven by our worn out and jaded men, as their forces out numbered us five to one. The fight continued all night, and not receiving reinforcements as expected from the main army we were obliged to withdraw and proceed to some other point. In doing so our Brigade was ordered to hold the enemy in check until the Division had crossed a stream in our rear. The enemy taking advantage of the movement, at once threw forward their whole force and completely surrounded us. We turned about, charged to the rear to gain our horses. Some succeeded in doing so, others were killed or wounded, and those who straggled, as a general thing, were taken prisoners. Major Moore and myself, with one hundred men, were not able to gain our horses. Seeing that we were entirely cut off from the command we took to the woods, closely followed by the enemy who made several charges upon us, but were repulsed each time. After an hour we succeeded in getting away from them. By looking upon the map we found that we were some fifty miles from our lines, the way we would have to march to gain them. Tired and worn out, without rations, and had been two days with only one cup of coffee, this to us looked very discouraging to march that distance in the enemy’s country and not be discovered or captured. But we asked ourselves which would be profitable, falling in the hands of the enemy or stand a fatiguing march of three or four days until we could gain our lines. We chose the latter. On we started, marching a north-westerly course keeping in the woods, when suddenly we came upon a rebel camp. They discovering us, charged on our small band and captured thirty-five men and five officers. The rest of us succeeded in getting away. We hid in the woods until dark then took up the line of march, the next morning procuring a negro for a guide. He brought us safely to the Nottaway river. This we were obliged to ford as the enemy were guarding the bridges. We were compelled to throw away most of our clothing to enable us to get away. Water in this section was very scarce and we were obliged to drink from stagnant pools by the wayside. Weary and footsore we gained our lines. From here we were carried in wagons to join our regiment near Light House Point, Va., where we are lying at present resting ourselves and our jaded horses. The loss of the regiment is 129 killed, wounded and missing. William Long and Nelson Evans were among the missing. The loss of my company was 13. At present we are resting on the banks of the James river, in full view of all the shipping. From our point of view can be seen flags representing the greatest nations of the earth. We shall move in a few days.

Yours in haste,

H.B. COMPSON,

Comd’g. Co. D, 8th N.Y. Cav.

The Wilson–Kautz Raid:

had the intended effect of disrupting Confederate rail communications for several weeks, the raiding force lost much of its artillery, all of its supply train, and almost a third of the original force, mostly to Confederate capture.

Here’s a recap of the 8th’s experience during the raid from Colonel William L. Markell:

The Eighth went to Petersburg, and did picket duty in the vicinity of Prince George Court House until the date of General Wilson’s raid. Accompanying the raid the regiment lost heavily,— on June 22d, cutting their way through the Rebel right at Reams’ Station, on the 23d, at Black and Whites, to near Nottoway Court House, where the brigade being cut off from the main command had an afternoon and all night’s battle, sustaining a loss of 90 men. On the 24th, it succeeded in joining the command at Meherrin Station, on the Dansville Railroad; on the 25th, to Roanoke Creek; and at night, to Staunton River; 27th, to Meherrin River; 28th, to Stony Creek Station, on the Weldon Railroad, in rear of the Rebel lines,, where all the afternoon and night they were trying to cut their way through, but were again headed off by the enemy and forced to make their way back south nearly to the North Carolina line. After enduring untold hardships, they at last found their way into the Union lines, the regiment losing nearly one-third of its number.

You can read more about the raid and the 22nd New York Cavalry’s role in it here.

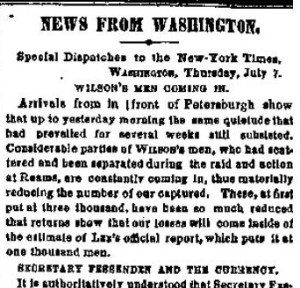

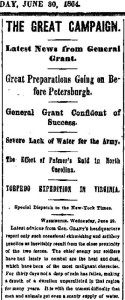

As indicated by The New-York Times report at the left the scattered raiders were still making it back to Union lines as of July 7th.

Hal Jespersen’s map is licensed by Creative Commons

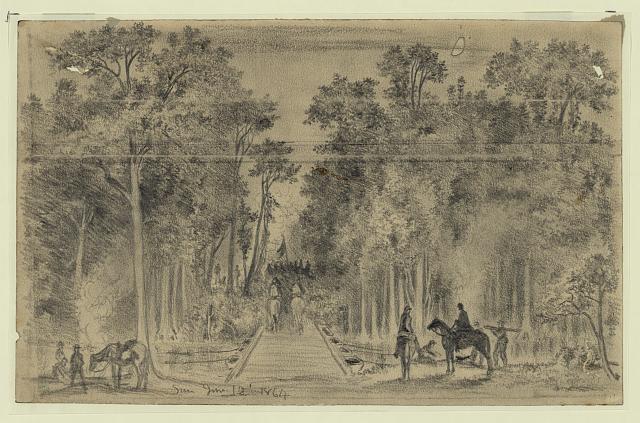

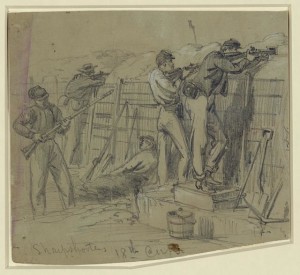

Alfred R. Waud’s drawing was published in the July 30, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly at Son of the South