A Democrat-leaning publication in upstate New York was skeptical about claims of a Union victory at the Battle of Franklin. From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in December 1864:

The Battle at Franklin.

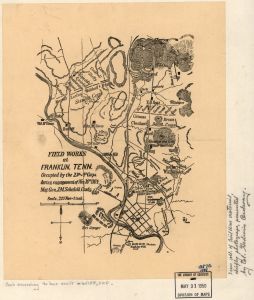

The battle of Franklin, Tenn., on the 30th ult., between the Federal forces under Thomas, and the Confederates under the Hood, resulted as we predicted last week, in the virtual defeat of our army. It was a battle forced by the Confederates, and the falling back of our forces to Nashville, a distance of twenty miles, during the night and before hostilities had fairly ceased, bears us out in this assertion. The Confederates followed up their success, and are now besieging Nashville. The first report placed their loss at six thousand, and ours at only six hundred. A second report brings the rebel loss down to two thousand, and owns a loss on our side of fifteen hundred. If the truth could be known we venture to say that one side suffered quite as much as the other.

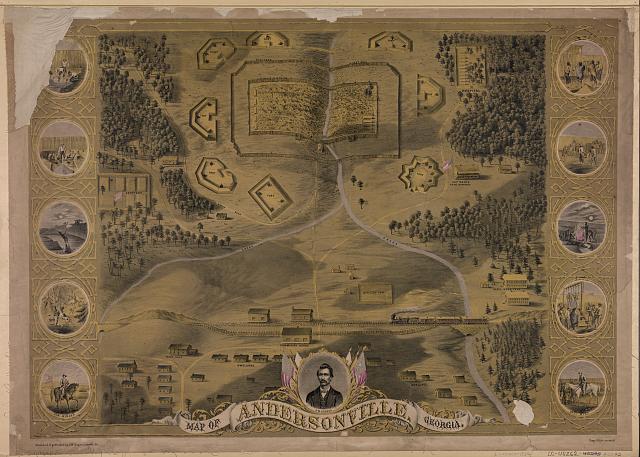

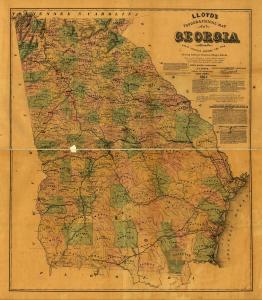

Since Gen. Hood’s army crossed the Tennessee river, our forces have gradually retreated. The enemy has driven us from Decatur, Huntsville, Shelbyville and Pulaski. At Columbia, Hood attacked and defeated our army, and then Thomas retreated across the Duck river and made a stand at Franklin, a strongly fortified town. Here he was again attacked with great impetuosity by Hood, and here he again retreated. This, in brief, is the result of the campaign in Tennessee. Does anyone believe if the rebels were as “disastrously” defeated as reported, they would now be laying siege to Nashville?

That’s virtually the same question a Southern newspaper asked. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch December 5, 1864:

Monday morning…December 6 [5], 1864.

From the Yankee accounts of their victory at Franklin over Hood, it must have been the strangest victory on record, except that gained by Banks over Dick Taylor last spring. It seems that Hood attacked Schofield works at 4 o’clock, nearly sunset, was at first victorious, carried the lines of the Yankees, and was then outflanked and beaten so badly that but for night coming on he would have been annihilated. In the little time that elapsed between 4 o’clock and dark, on the 1st of December, he lost six thousand men, killed and wounded, and one thousand prisoners! All this is truly wonderful! But the courtesy and urbanity of Schofield and Thomas are more marvellous than anything else.–After having defeated Hood so terribly, their politeness did not allow them to stay on the field and witness his humiliation the next day. So, in the night, they fell back to within four miles of Nashville, where they say they hold a splendid position. There they assert that the crowning battle is to be fought, and that Thomas is very confident. They had apologized before for falling back to Franklin. They said they did so because it was such an admirable position. Now they have abandoned it, after having gained a splendid victory!

These lies are too gross for belief. Our opinion is, that Thomas has been badly beaten, and has fallen back because he cannot help it.

The numbers lost at Franklin was adjusted in another article from a Seneca County, New York newspaper in December 1864:

OUR LOSS AT THE BATTLE OF FRANKLIN. – Our loss in the battle of Franklin turns out to have been much larger than at first reported. It was over two thousand in killed wounded and missing. We lost nearly as many prisoners as we took – that is, about a thousand. This loss occurred when our lines were broken, early in the battle.

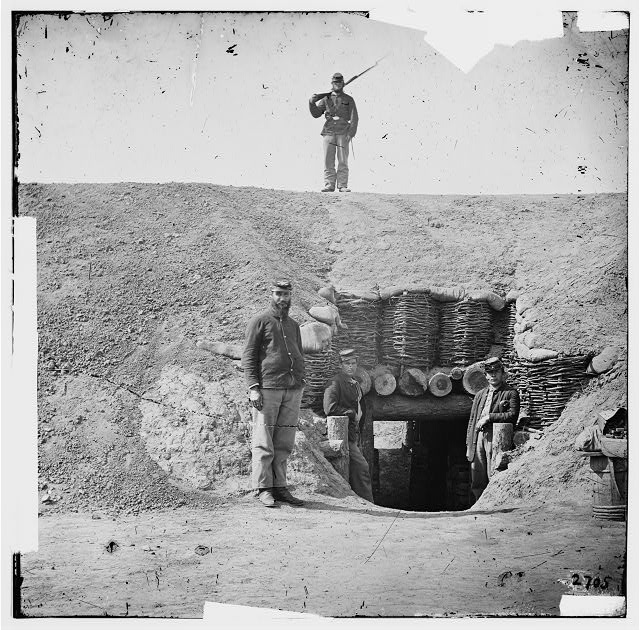

![[Atlanta, Ga. Gen. William T. Sherman on horseback at Federal Fort No. 7]; by Geore N. Barnard,1864; LOC:](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/03379r-252x300.jpg)