![Ruins on Carey Street, Richmond, Va., April, 1865 ( photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34918)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/34918r-300x236.jpg)

after “Pandemonium broken loose” (Ruins on Carey Street, Richmond, Va., April, 1865 (Library of Congress))

Another Monday morning in Richmond. Another pugnacious editorial from the

Daily Dispatch? No, as the paper explained eight months later, it went temporarily out of business

150 years ago today as Richmond burned and the Union army entered the city. From the

Richmond Daily Dispatch December 9, 1865:

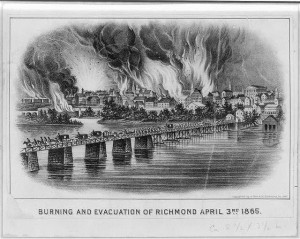

… In this struggle the Dispatch took its part. It was honest and earnest; and does not mean to retreat, or, in the every day parlance, to crawfish from its position. It sympathised with the Confederacy, did all it could to cheer the hearts of the people in the struggle, and continued with it, and, we may say, fell with it in the calamitous fire of the 3d of April. Its voice was heard up to that hour. While the carrier conveyed its communications to the public in one part of the city, its types and presses were melting in the fires of another. …

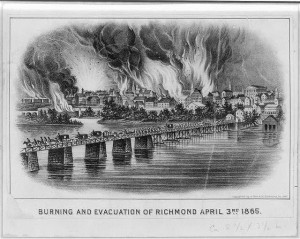

After exploding his ironclads about 3 AM on April 3rd, Raphael Semmes had to get his sailors ashore and free of Richmond in order to join up with the Confederate army. His memoirs were published four years after the fact – about a Civil War’s length of time. He and his men made a train and got out of the Richmond area and traveled to Danville. From the Manchester side of the James, he observed the conflagration in Richmond, the panic of some of its citizens, and the Union army (made up of black and white savages) entering the city. From Memoirs of Service Afloat, During the War Between the States (1869) (pages 812-816) by Raphael Semmes:

There are several bridges spanning the James between Drury’s Bluff and the city, and at one of these we were detained an hour, the draw being down to permit the passage of some of the troops from the north side of the river, who had lighted the bonfires of which I have spoken. Owing to this delay, the sun—a glorious, unclouded sun, as if to mock our misfortunes—was now rising over Richmond. Some windows, which fronted to the east, were all aglow with his rays, mimicking the real fires that were already breaking out in various parts of the city. In the lower part of the city, the School-ship Patrick Henry was burning, and some of the houses near the Navy Yard were on fire. But higher up was the principal scene of the conflagration. Entire blocks were on fire here, and a dense canopy of smoke, rising high in the still morning air, was covering the city as with a pall. The rear-guard of our army had just crossed, as I landed my fleet at Manchester, and the bridges were burning in their rear. The Tredegar Iron Works were on fire, and continual explosions of loaded shell stored there were taking place. In short, the scene cannot be described by mere words, but the reader may conceive a tolerable idea of it, if he will imagine himself to be looking on Pandemonium broken loose.

![Ruins near arsenal and Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Va., April, 1865 (photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34936)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/34936r-300x225.jpg)

“Ruins near arsenal and Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Va., April, 1865” (Library of Congress)

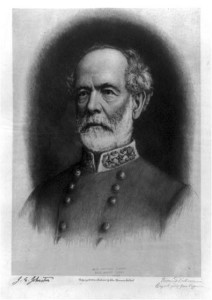

“Burning and Evacuation of Richmond, April 3, 1865” (Library of Congress)

Yes; here were my “forces,” but where, the d—l, was General Lee, and how was I to join him? If I had had the Secretary of the Navy, on foot, by the side of me, I rather think this latter question would have puzzled him.

But there was no time to be lost,—I must do something. The first thing, of course, after landing my men, was to burn my wooden gunboats. This was done. They were fired, and shoved off from the landing, and permitted to float down the stream. I then “put my column in motion,” and we “marched” a distance of several squares, blinded by the dust kicked up by those vagabonds on horseback, before mentioned. When we came in sight of the railroad depot, I halted, and inquired of some of the fugitives who were rushing by, about the trains. “The trains!” said they, in astonishment at my question; “the last train left at daylight this morning—it was filled with the civil officers of the Government.” Notwithstanding this answer, I moved my command up to the station and workshops, to satisfy myself by a personal inspection. It was well that I did so, as it saved my command from the capture that impended over it. I found it quite true, that the “last train” had departed; and, also, that all the railroad-men had either run off in the train, or hidden themselves out of view. There was no one in charge of anything, and no one who knew anything. But there was some material lying around me; and, with this, I resolved to set up railroading on my own account. Having a dozen and more steam-engineers along with me, from my late fleet, I was perfectly independent of the assistance of the alarmed railroad-men, who had taken to flight.

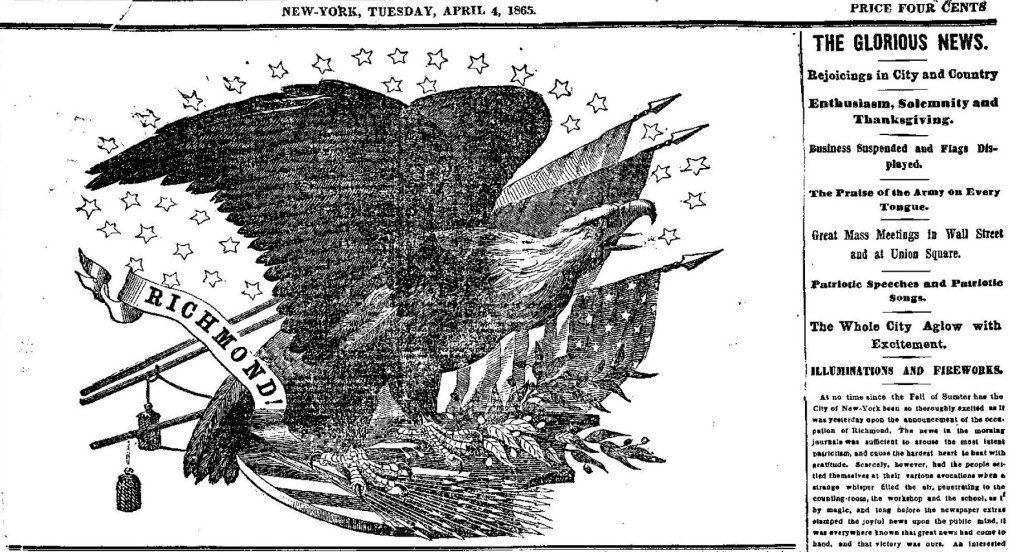

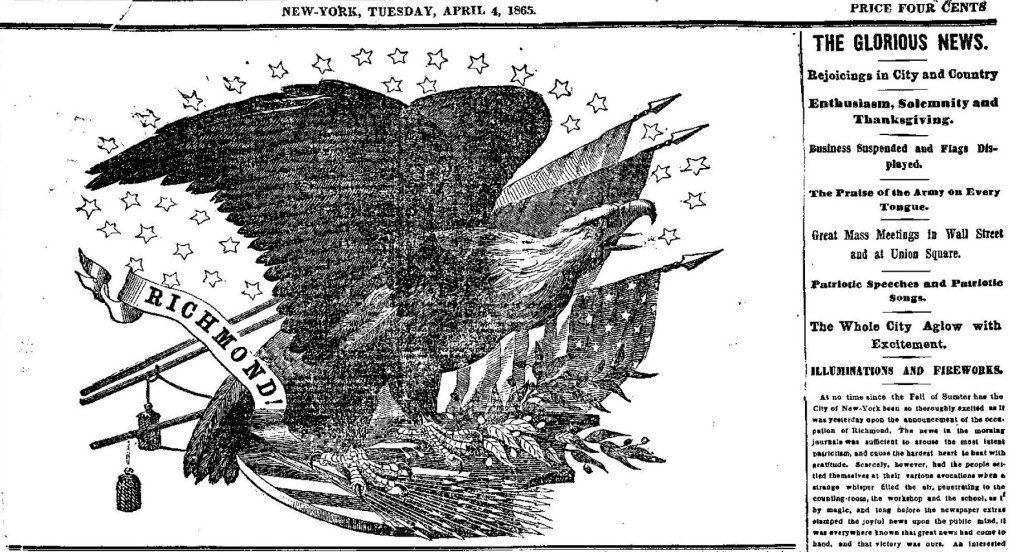

NY Times 4-4-1865

A pitiable scene presented itself, upon our arrival at the station. Great numbers had flocked thither, in the hope of escape; frightened men, despairing women, and crying children. Military patients had hobbled thither from the hospitals; civil employees of the Government, who had missed the “last train,” by being a little too late, had come to remedy their negligence; and a great number of other citizens, who were anxious to get out of the presence of the hated Yankee, had rushed to the station, they scarcely knew why. These people had crowded into, and on the top of, a few straggling passenger-cars, that lay uncoupled along the track, in seeming expectation that some one was to come, in due time, and take them off. There was a small engine lying also on the track, but there was no fire in its furnace, no fuel with which to make a fire, and no one to manage it. Such was the condition of affairs when I “deployed” my “forces” upon the open square, and “grounded arms,”—the butts of my rifles not ringing on the ground quite as harmoniously as I could have desired. Soldiering was new to Jack; however, he would do better by-and-by.

My first move was to turn all these wretched people I have described out of the cars. Many plaintive appeals were made to me by the displaced individuals, but my reply to them all was, that it was better for an unarmed citizen to fall into the hands of the enemy, than a soldier with arms in his hands. The cars were then drawn together and coupled, and my own people placed in them. We next took the engine in hand. A body of my marine “sappers and miners” were set at work to pull down a picket fence, in front of one of the dwellings, and chop it into firewood. An engineer and firemen were detailed for the locomotive, and in a very few minutes, we had the steam hissing from its boiler. I now permitted as many of the frightened citizens as could find places to clamber upon the cars. All being in readiness, with the triumphant air of a man who had overcome a great difficulty, and who felt as if he might snap his fingers at the Yankees once more, I gave the order to “go ahead.” But this was easier said than done. The little locomotive started at a snail’s pace, and drew us creepingly along, until we reached a slightly ascending grade, which occurs almost immediately after leaving the station. Here it came to a dead halt. The firemen stirred their fires, the engineer turned on all his steam, the engine panted and struggled and screamed, but all to no purpose. We were effectually stalled. Our little iron horse was incompetent to do the work which had been required of it. Here was a predicament!

“Richmond, Va. Grounds of the ruined Arsenal with scattered shot and shell” (Library of Congress) [and some savage occupiers]

service no longer afloat

It was thus, after I had, in fact, been abandoned by the Government and the army, that I saved my command from capture. I make no charges—utter no complaints. Perhaps neither the Government, nor the army was to blame. The great disaster fell upon them both so suddenly, that, perhaps, neither could do any better; but the naked fact is, that the fleet was abandoned to shift for itself, there being, as before remarked, not only no transportation provided for carrying a pound of provisions, or a cooking-utensil, but not even a horse for its Admiral to mount. As a matter of course, great disorder prevailed, in all the villages, and at all the way-stations, by which we passed. We had a continual accession of passengers, until not another man could be packed upon the train. So great was the demoralization, that we picked up “unattached” generals and colonels on the road, in considerable numbers. The most amusing part of our journey, however, was an attempt made by some of the railroad officials to take charge of our train, after we had gotten some distance from Richmond. Conductors and engineers now came forward, and insisted upon regulating our affairs for us. We declined the good offices of these gentlemen, and navigated to suit ourselves. The president, or superintendent of the road, I forget which, even had the assurance to complain, afterward, to President Davis, at Danville, of my usurping his authority! Simple civilian! discreet railroad officer! to scamper off in the manner related, and then to complain of my usurping his authority! My railroad cruise ended the next day—April 4th—about midnight, when we reached the city of Danville, and blew off our steam, encamping in the cars for the remainder of the night. Our escape had been narrow, in more respects than one. After turning Lee’s flank, at the Five Forks, the enemy made a dash at the Southside Railroad; Sheridan with his cavalry tearing up the rails at the Burksville Junction, just one hour and a half after we had passed it.

On to Richmond – at last (New York Times 4- 4 -1865

At least it is getting pretty near the end. The Dispatch has been a huge source of material for this blog over the past four years.

![Union soldiers and band marching through a city street on their way to join the Civil War (Hartford, Ct. : Calhoun Show Print., [between 1880 and 1900]; LOC: LC-USZC4-1446)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/3b52950r.jpg)

![[Richmond, Va. Crippled locomotive, Richmond & Petersburg Railroad depot] (1865; LOC: LC-DIG-cwpb-02704)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/02704r.jpg)

![Ruins on Carey Street, Richmond, Va., April, 1865 ( photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34918)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/34918r-300x236.jpg)

![Ruins near arsenal and Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Va., April, 1865 (photographed 1865, [printed between 1880 and 1889]; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca-34936)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/34936r-300x225.jpg)