It was supposed to be a very good Good Friday, at least for the Union. In a celebratory ceremony 150 years ago today Robert Anderson raised the old Union flag from April 1861 over Fort Sumter, which was once again in Federal hands. However, a Democratic paper in upstate New York objected to leading abolitionists attending the event on the Government’s dime. Why should the people who caused the war and denigrated the Union be allowed to lead the celebration of the North’s successes? The editorial closed by looking forward to eventual vengeance against the abolitionists.

“Charleston, South Carolina. Flag-raising ceremony at Fort Sumter. Arrival of Gen. Robert Anderson and guests” (Library of Congress)

From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in April 1865:

The authorities at Washington have resolved to commemorate this day (April 14th.,) by re-elevating over the walls of Fort Sumter the flag which four years ago was surrendered to the power of the boasted Southern Confederacy. To this end government vessels were fitted up and all the leading abolition agitators of the North invited to be present, at government expense, and assist on the occasion. The raising of the “old flag” over Sumter is well enough, perhaps, but to invite George Thompson, William Lloyd Garrison and Henry Ward Beecher, to be prominent actors of the occasion, is an insult to the pride and patriotism of the American people. George Thompson is the English abolitionist, who first helped to awaken here the sectional animosity which finally led to civil war. And he, in company with Lloyd Garrison and Ward Beecher and other noted abolitionist [sic] – men who, with the New York Tribune, denominated the American banner “hate’s polluted rag” are chosen by the authorities to share the exclusive privilege, at government expense, of re-elevating the “old flag” over the ruins of conquered Charleston. These very men, who openly proclaimed that flag a “flaunting lie,” and who called upon every man to trail it in the dust, are the ones selected to shout hosannas over Union victories, which better men did so much, and which they did nothing whatever with their right arms to secure! But so it is, and the people must wait for the disappearance of the “Southern Confederacy” from the scene, before they turn upon the Beechers and the Garrisons, their vengeance for all the horrors and sufferings of the past four years.

A Confederate sympathizer from Maryland didn’t wait that long to put a bullet-hole in the head of Abraham Lincoln. The President was successfully coercing the rebel states back into the Union. If Mr. Lincoln was not the most publicly rabid of abolitionists, he had certainly become, during the course of the war, the Emancipator-in-Chief.

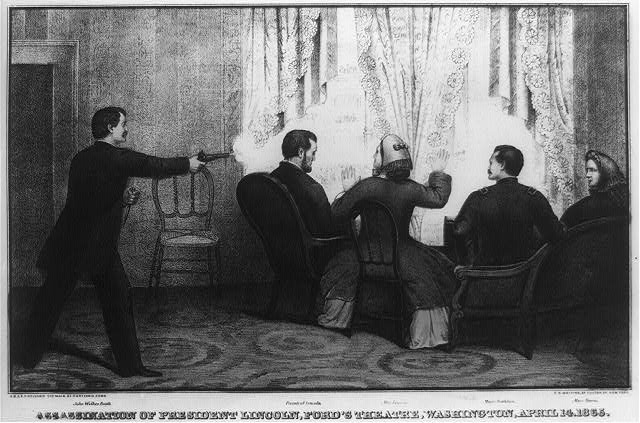

During the evening of April 14, 1865 President and Mrs. Lincoln made their way Ford’s Theatre to enjoy a play. Once in the presidential box the President held Mary’s hand:

Pleased by the attention he had shown her on their carriage ride that afternoon, and now by this further expression of affection, Mary Lincoln reverted to her old role of Kentucky belle. “What will Miss Harris think of my hanging onto you so?” she whispered, leaning toward him. Lincoln’s eyes fixed on the stage, reflected the glow of the footlights. “Why, she will think nothing about it,” he said, and he kept his grip on her and.

Act I ended; Act II began. Down in Charleston the banqueters raised their glasses in response to Anderson’s toast, and here at Ford’s, in an equally festive mood, the audience enjoyed Our American Cousin with only occasional sidelong glances at the State box to see whether Grant had arrived. … Act II ended; Act III began. Lincoln, having at last released his wife’s hand and settled back in the horsehair rocker, seemed to be enjoying what was happening down below. … [lines in the play]

Then it came, a half-muffled explosion, somewhere between a boom and a thump, loud but by no means so loud as it sounded in the theater, then a boil and bulge of bluish smoke in the presidential box …[1]

Apparently the first part of the following article is lost to the ages. From a Seneca County, New York newspaper in 1865:

The blood oozed from the wound at the back of his head. The surgeons exhausted every effort of medical skills, but all hope was gone. The parting of his family with the dying President is too sad for description.

By midnight, the Cabinet, with Messrs. Sumner, Colfax and Farnsworth, Judge Curtis, Gov. Oglesby, Gen. Meigs, Col. Hay and a few personal friends, with Surgeon-General Barnes and his immediate assistants, were around his bedside.

The President and Mrs. Lincoln did not start for the theatre until fifteen minutes after eight o’clock. Speaker Colfax was at the White House at the time, and the President stated to him that he was going, although Mrs. Lincoln had not been well, because the papers had announced that General Grant and they were to be present, and, as Gen. Grant had gone North, he did not wish the audience to be disappointed.

He went with apparent reluctance and urged Mr. Colfax to go with him; but that gentleman had made other arrangements, and with Mr. Ashman [Ashmun?], of Massachusetts, bid him good bye.

When the excitement at the theatre was at its wildest height, reports were circulated that Secretary Seward had also been assassinated.

On reaching this gentleman’s residence a crowd and a military guard were found at the door, and on entering it was ascertained that the report was based on truth.

Everybody there was so excited that scarcely an intelligible word could be gathered, but the facts are substantially as follows:

At about 10 o’clock a man rang the bell, and the call having been answered by the colored servant, he said he had come from Dr. Verdi, Secretary Seward’s family physician, with a prescription, at the same time holding in his hand a small piece of folded paper, and saying in answer to a refusal that he must see the Secretary, as he was entrusted with particular directions concerning the medicine.

He still insisted on going up, although repeatedly informed that no one could enter the chamber. The man pushed the servant aside, and walked heavily towards the Secretary’s room, and was then met by Mr. Frederick Seward, of whom he demanded to see the Secretary, making the same representation which he did to the servant. What further passed in the colloquy is not known, but the man struck him on the head with a “billy,” severely injuring the skull and felling him almost senseless. The assassin then rushed into the chamber and attacked Major Seward, Paymaster of the United States army and Mr. Hansell, a messenger of the State Department and two male nurses, disabling them all, he then rushed upon the secretary, who was lying in bed in the same room, and inflicted three stabs in the neck, but severing, it is thought and hoped, no arteries, though he bled profusely.

The assassin then rushed down stairs, mounted his horse at the door, and rode off before an alarm could be sounded, and in the same manner as the assassin of the President.

It is believe [sic] that the injuries of the Secretary are not fatal, nor those of either of the others, although the Secretary and the Assistant Secretary are very seriously injured.

Secretary Stanton and Wells, and other prominent officers of the Government, called at Secretary Seward’s house to inquire into his condition, and there heard of the assassination of the President.

They then proceeded to the house where he was lying, exhibiting of course intense anxiety and solicitude. An immense crowd was gathered in front of the President’s house and a strong guard was also stationed there, many persons evidently he would be brought to his home.

The entire city tonight presents a scene of wild excitement, accompanied by violent expressions indignation, and the profoundest sorrow – many shed tears. The military authorities have despatched mounted patrols in every direction in order if possible to arrest the assassins.The whole Metropolitan police are likewise vigilant for the same purpose.

The attack, both at the theatre and at Secretary Seward’s house, took place at about the same hour – 10 o’clock – tus showing a preconcerted plan to assassinate these genmen [sic].

- [1]Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative. Vol. 3. Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1986. Print. page 979-980.↩