Above the entrance to the ferry way appears the inscription: “WASHINGTON, the Father; LINCOLN, the Savior of his country.”

150 years ago today the remains of President Lincoln and his son Willie were conveyed from Philadelphia to New York City. The embalmer dusted off Mr. Lincoln’s face before the funeral train left Philadelphia.

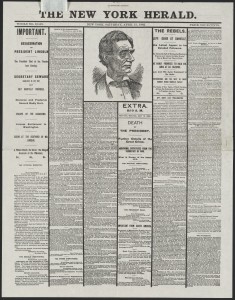

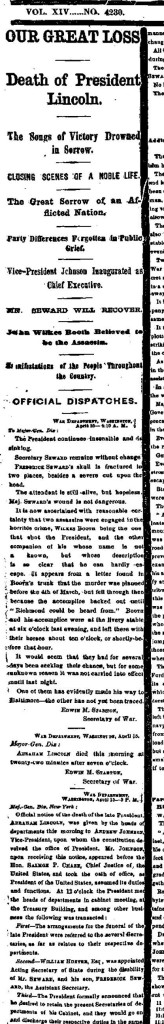

From The New-York Times April 25, 1865:

THE FUNERAL CORTEGE.; FROM PHILADELPHIA TO NEW-YORK.

PHILADELPHIA, Monday, April 24.

The funeral party started from the Continental Hotel at 2 o’clock this morning, and halted before the State House until the coffin was conveyed to the hearse.

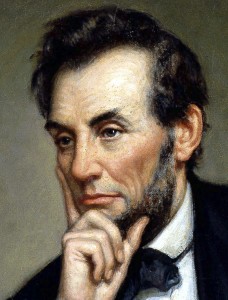

The transparency which adorned the front of the building, namely, the portrait of the late President, with a dark border representing a coffin, afforded a relief to the surrounding gloom of the morning — the words, “Rest in Peace” still blazing from the gas-jets.

The Invincibles, a city organization, with torches, composed a part of the procession, and the City Guard acted as the escort. A band of music played dirges on the march.

The procession reached Kensington Station at 4 o’clock. Thousands of men, women and children were still in the streets, and not a few half-dressed residents in that neighborhood, who, apparently, had just hurried from their beds, ran forward to join the already large crowd in waiting at the depot. The funeral party with difficulty pressed their way to the cars. …

At a few minutes after 4 o’clock the train started. A locomotive preceded it by ten minutes. The en]g]ine is trimmed with the national flag draped with mourning, and there is a telegraph and two signal men accompanying it to guard against accidents.

The train consisted of nine elegant cars, provided by the Camden and Amboy Railroad, all tastefully trimmed.

The funeral car last night was additionally decorated, heavy silver fringe being placed at the end of the black coverings of the several panels, and the festoon being fastened with stars and tassels of similar material. First Lieut. JAMES A. DURKEE, Lieut. MURPHY and Sergeants C. ROWHART, S. CARPENTER, A.C. CROMWELL and J. MCINTOSH, spent the entire of last night in thus improving the exterior of the car, and clothing the interior with additional drapery. The materials were contributed by citizens of Philadelphia. … [occupants of the several cars in the train]

The Guard of Honor occupied the next car, and after this was that containing the remains of the late President and his little son WILLIE.

The last car was occupied by Rear Admiral Davis, Major-Generals Dix and Hunter, Brig. Gen. Townsend, Assistant Adjutant General of the United States Army. (Adjt-Gen. Thomas is detained at home by sickness.) Brevet Brig.-Gen. Barnard, Gens. Caldwell, Eaton, Ramsey, Maj. Field of the Marine Corps, Capt. Taylor and Capt. Penrose, and other army and navy officers.

PHILADELPHIA, Monday, April 24.

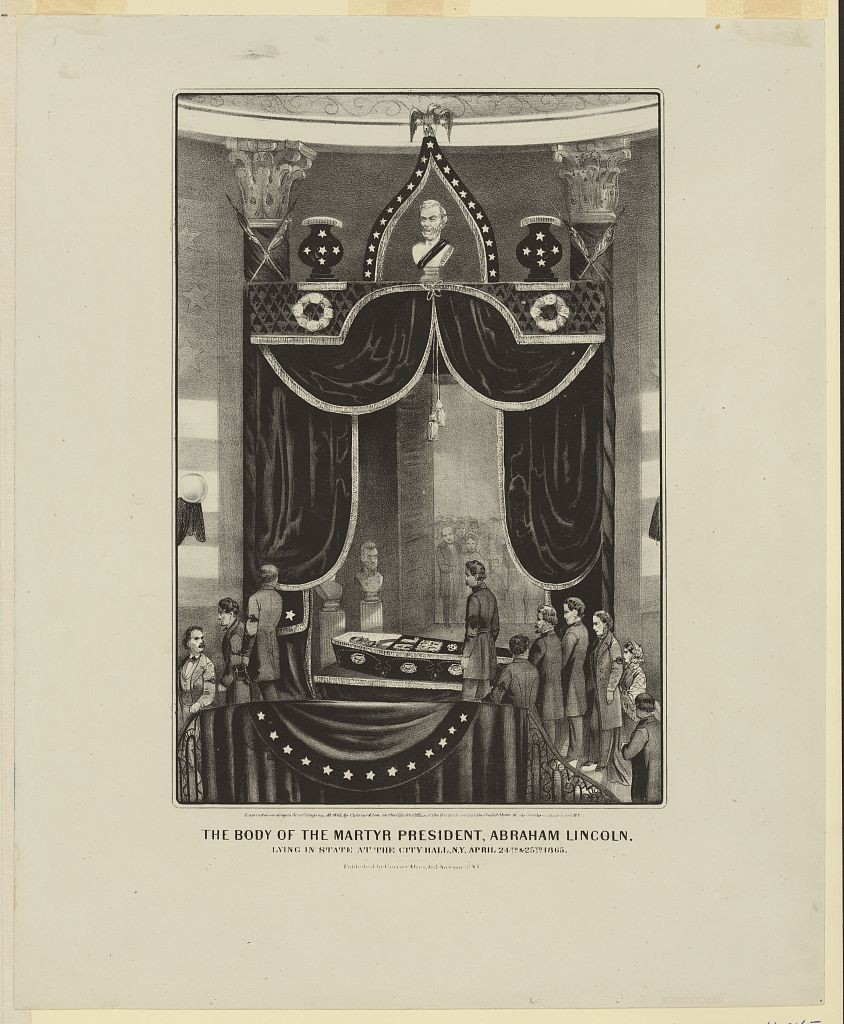

The body of President LINCOLN remained in state till 1 o’clock this morning, when the entrances were closed, all the throng having had an opportunity of viewing the remains.

Dr. BROWN, the embalmer, removed the dust that had settled on the face, and preparations were made for the departure of the body. At 3 o’clock the body was placed in the hearse, and the line of march taken for the Trenton Railroad Depot. …

The Delaware River, which separates the State of Pennsylvania from that of New-Jersey, was crossed at 5 1/2 o’clock; and as the trains passed through Trenton, the bells of the city were tolled. Immense throngs of spectators had here gathered. Every hilltop and the line of the road, and other advantageous points, were largely occupied. The train proceeded onward until it reached the station, where it stopped for thirty minutes. The population here had assembled in much larger numbers, for this was the more attractive point.

The station was elaborately festooned, and the national banner draped with crape was a prominent feature. There was a detachment of the Reserved Veteran and Invalid Corps drawn up in line on the platform, giving the customary funeral honors. Music was performed by an instrumental band, minute guns were fired, the bells continuing to toll.

A number of persons rushed from various directions toward the car containing the body of the President, but the masses generally retained their standing positions, evidently showing they were satisfied to restrain their impatience for a few minutes until the car should pass before them.

Absorbed in the general interest of the scene, it did not occur to the male part of the throng that a general lifting of the hat would have been a silent but becoming mark of respect to the dead. Everywhere, however, the emblems of mourning were prominent, showing that the people of Trenton, like all other true patriots, were not unmindful of the great loss which has befallen the nation in the violent death of a beloved and honored President. …

[New-Brunswick, Ranway, Elizabeth, Newark, Jersey City] …

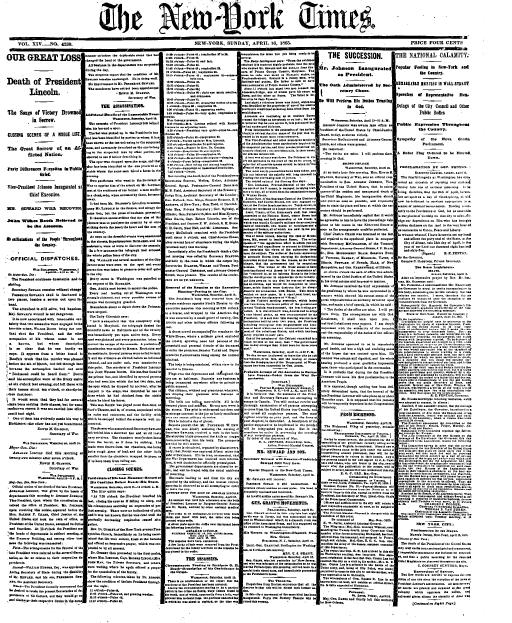

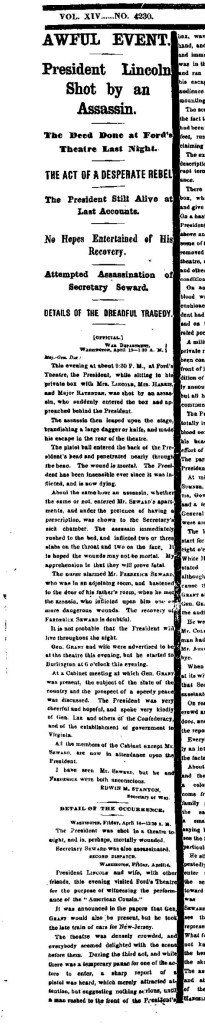

From The New-York Times April 25, 1865:

THE REMAINS IN NEW-YORK.

The funeral train conveying the remains of President LINCOLN, left Newark at 9:07 yesterday morning, in charge of Mr. COULTER, the senior conductor of the road, the same officer who was conductor of the train in which Mr. LINCOLN went on to Washington.

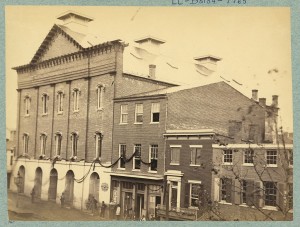

While the cars were passing onward toward Jersey City, the people of that place were gathering at windows and roofs, filling the streets, and occupying all possible points of view around the great station-house at the ferry way.

THE SCENE WITHIN THE STATION-HOUSE

was very quiet, but very impressive. The train was due about 10 o’clock. Much before 9 the balcony that runs round the interior of the station-house began to be occupied by ladies and their escorts. Along the front of the balcony, around the whole vast interior, hung one single broad band of black cloth, relieved with white stripes crossed diagonally. At the eastern end was a large national five draped and festooned in mourning, with the impressive motto, “Be still, and know that I am God,” and at the opposite extremity, the station clock was heavily draped in black and stopped at the hour of the President’s death, with the motto, “A nation’s heart is struck,” and the date of the deed.

ARRIVAL.

A guard of two hundred regulars from the Second and Sixth United States Infantry, under Capt. LIVINGSTON and Maj. MCLAUGHLIN, is posted in and around the station. As the hour for the arrival of the funeral train approaches, the squad within the station-house, standing at ease, with stacked arms, is suddenly ordered into line. They form and march, the words of command sounding out clearly in the great empty, quiet, vaulted room; and a line of sentinels is posted at short distances along the midmost of the five tracks that run lengthwise through the house. The galleries are slowly filling up; the spacious floor of the great room is almost empty. A low murmur of conversation comes from the balcony; the noise and bustle of the ferry passengers sounds loudly from without, and every minute or two the brazen clash of an engine-bell breaks suddenly in from the tracks outside of the western gates; the long line of sentinels, with ba[y]onets fixed, moves waveringly hither and thither; the rest of the squad stand at ease, with arms stacked; the representatives of the press are conversing together in a group; all the faces are grave; there is a hush in the whole feeling of the place, enhanced by the vast empty space of the station-house, so silently awaiting the entrance of the corpse of the dead ruler of the land.

Mr. Secretary of State DEPEW, and Mr. Police Commissioner ACTON, quietly enter the building; a little afterward, the delegations from the municipalities of Jersey City, Hoboken, and Bergen, file in; then the Saengerbund, or united German Singing Societies of Hoboken, come and take their place. Brig. Gen. HATFIELD, commanding the Hudson brigade of New-Jersey State troops, Brig.-Gen. HUNT, commanding the troops in the harbor and defences of New-York, and a few other officers, enter, Beyond the gates, glimpses can be seen of silent crowds piled like drifts of light snow on roofs, cars, and other elevated places.

The train is approaching. The line of sentinels is extended, quite cutting off the area within which the cars are to enter. Mr. WOODRUFF, the polite Superintendent of the railroad, is just in season to secure the reporters their professional immunities from military command.

Almost unheard, the nine cars of the funeral train, all draped with black, glide steadily in through the western gates of the station. Now the guards present arms; a battery of the Hudson County Artillery, at a little distance, fires minute guns; and the Saengerbund chants, in a great volume of strong and manly voices, with much feeling and good execution, an impressive Grabesruhe, or Requiem.

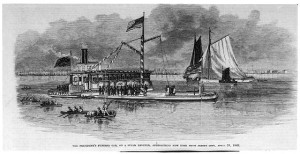

THE TRANSIT.

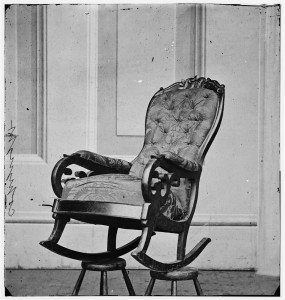

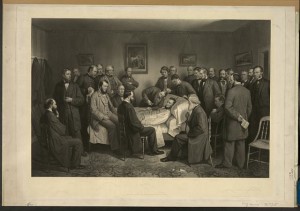

The last car of the train, the gorgeous and highly finished one built for President LINCOLN’s use while he was alive, is detached. That immediately in front of it, its sombre, almost black, paneling contrasting strongly with the strong crimson of the other, was finished expressly for its present sad purpose. The civic and military delegation who have escorted the body of the dead from Washington, gather to the door of this funeral car. All heads are uncovered, and the coffin is reverently borne forth by soldiers of the Veteran Reserves, and carried to the hearse. As it leaves the station-house the deep voices of the Germans are silent, and the various delegations, forming into line, march slowly from the building by its western exit, pass down Exchange-place towards the ferry-boat; the Washington escort first, the Mayor and Common Council of New-York next, and the military and other civic bodies following.

Above the entrance to the ferry way appears the inscription: “WASHINGTON, the Father; LINCOLN, the Savior of his country.” A strong line of guards keeps clear a broad and ample space for the procession. Outside their line a great and dense but serious and silent crowd is gathered. All are quickly on board the boat, and moving at once out of the slip, she crosses without delay or accident to the foot of Desbrosses-street.

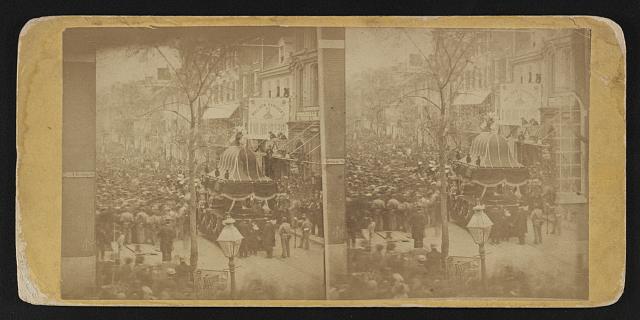

![Down Broadway, from below Wall St. ( New York : E. & H.T. Anthony & Co. [April 24, 1865]; LOC: C-DIG-stereo-1s04310)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/1s04310r-300x153.jpg)

“not one building without its signs of mourning” (Down Broadway, from below Wall St., 4-24-1865, Library of Congress)

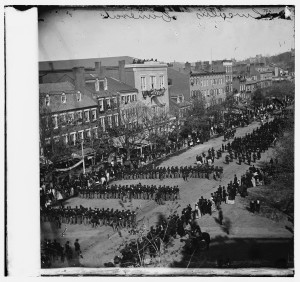

THE PROCESSION TO THE CITY HALL.

The Seventh Regiment and the police maintained a perfectly clear area throughout the whole space of Desbrosses-street, from end to end. As the boat entered the slip the singers again took their places near the hearse. The procession took order as it passed from the boat. The Seventh Regiment, already formed, took the right of the line, the hearse moving within a hollow square formed by its ranks. Next moved three lines of coaches, conveying the Washington escort, and the line was closed by the civic deputations.

Along the whole distance from the ferry the excellent police arrangements of the day maintained clear roadways. But the sidewalks, windows, roofs, posts, trees, all imaginable points for advantageous view, were crowded to their utmost capacity, and there was, it is believed, not one building without its signs of mourning.

Passing through this immense, almost soundless, but intensely interested and deeply sympathetic crowd by Desbrosses-street to Canal, by Canal to Broadway, down Broadway to the Astor House, up Park-row to the eastern side of the Park at Printing House-square, the procession moved slowly into the open space before the City Hall, and the gray lines of the Seventh Regiment marked the margin of the broad area already kept clear by the police. Within inner lines of soldiers, while the great audience in reverent silence uncovered their heads, the hearse halted before the main entrance of the City Hall.

![The procession approaching Union Square ([publisher not identified] [April 24, 1865]; LOC: LC-DIG-stereo-1s04309)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/1s04309r.jpg)

![Post office department. The nation mourns his loss. He still lives in the hearts of the people. [mourning badge]. (LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000551/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Post-Office-Mourns-157x300.jpg)

![Liberty and Union forever. Song, on the death of president Abraham Lincoln. By Silas S. Steele. [J. Magee, 316 Chesnut St., Phila.] [c. 1865] (LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/amss002302/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Liberty-and-Union-song-193x300.jpg)

![Andrew Johnson taking the oath of office in the small parlor of the Kirkwood House [Hotel], Washington, [April 15, 1865] (Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 21, 1866 Jan. 6, p. 245.)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/3a12553r-300x237.jpg)

![[Derringer gun John Wilkes Booth used to assassinate Abraham Lincoln.] Artifact in the museum collection, National Park Service, Ford's Theatre National Historic Site, Washington, D.C. (LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2010630695/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/04711v-300x189.jpg)