No man is fit to be an American statesman who is afraid of American ideas. Liberty is the boon of every man, and it carries with it civil rights and citizenship….

We must accept our own ideas. I believe in liberty and universal citizenship, and would give it to all, were they ten millions in number. …

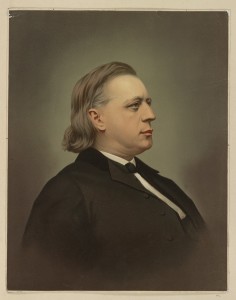

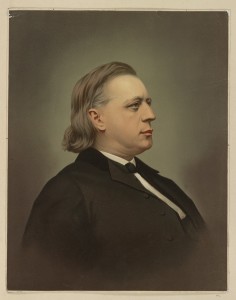

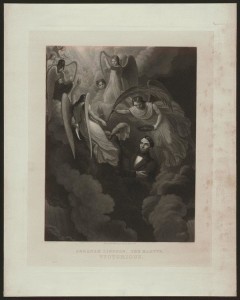

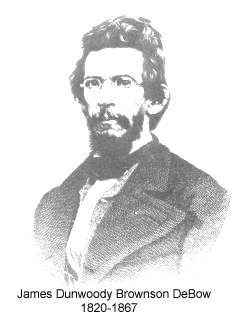

Preacher Beecher

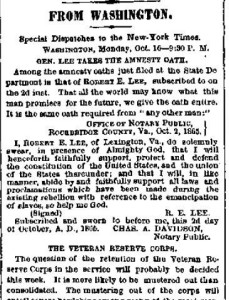

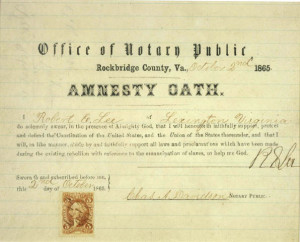

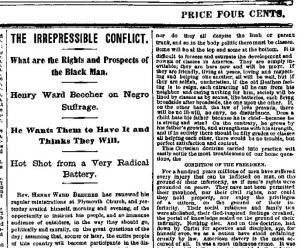

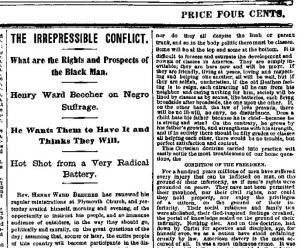

From The New-York Times September 25, 1865:

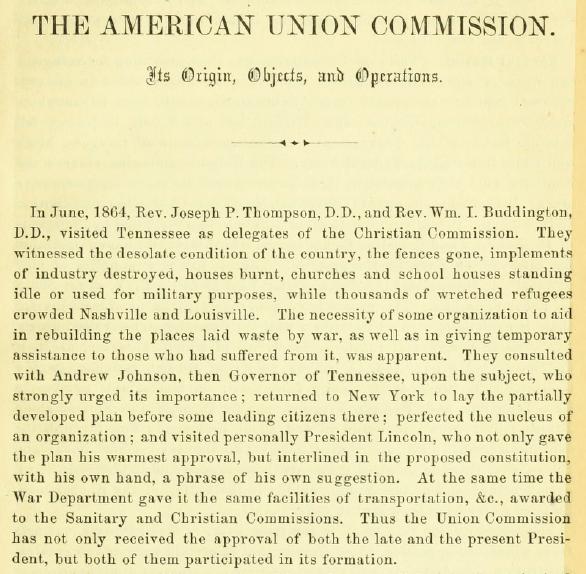

THE IRREPRESSIBLE CONFLICT.; What are the Rights and Prospects of the Black Man. Henry Ward Beecher on Negro Suffrage. He Wants Them to Have It and Thinks They Will. Hot Shot from a Very Radical Battery. …

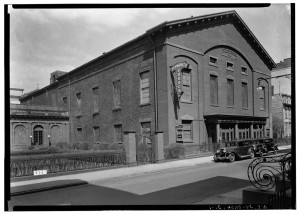

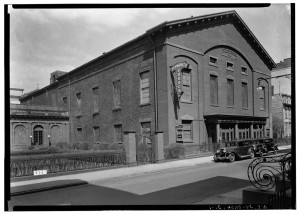

Rev. HENRY WARD BEECHER has renewed his regular ministrations at Plymouth Church, and yesterday availed himself, morning and evening, of the opportunity to instruct his people, and an immense audience of outsiders, in the way they should go, politically and morally, on the great questions of the day; assuming that, sooner or later, the entire people of this country will become participants in the discussion of negro suffrage. Mr. BEECHER, in the morning, preached a powerful sermon, drawn from the story of Christ washing his disciples’ feet, thereby inculcating the doctrine that the superior should, by virtue of his superiority, serve the inferior; that the Lord and Master should become the minister or servant, and that thenceforth the law of love, which insists upon the extension of aid and service from the strong to the weak, should be enforced. This example, set by the founder of the Christian religion, is before all his followers, and what was done by him has become the duty of every man.

“In the evening the house was packed at an early hour.”

In the evening the house was packed at an early hour. The aisles and several spaces near the pulpit were occupied, and it would have been difficult for Mr. WELD or any of his numerous assistants to find a seat for another listener. The Speaker of the House of Representatives, Hon. SCHUYLER COLFAX, sat in the pastor’s pew, and many white chokered gentlemen sat at the feet of the Brooklyn Gamaliel.

After the customary introductory services, Mr. BEECHER took his text from the 6th verse of the 11th chapter of Matthew, and proceeded substantially as follows:

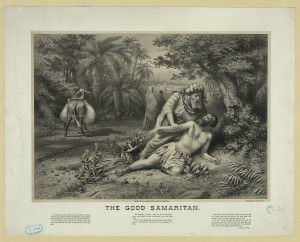

He first analyzed the passage and considered the circumstances under which it was brought forth. In a running commentary of pith and suggestive application, he described the cheerful condition of individual bitterness and national hostility in which lived the Jews and the Samaritans, and showed the moral courage requisite for a man to dare to narrate in the City of Jerusalem a parable of which the central figure and hero was a poor, despised Samaritan.

Inquiring next what was meant by “preaching good tidings to the poor,” Mr. BEECHER argued that since the world began it had been the custom to be kind to the poor, to do good to people in distress, but it was regarded rather as a virtue in those who did so, and Christ came to teach a new and antagonistic doctrine. He preached a doctrine that regarded every member of the human race a child of God — the universal Father; he regarded them as members one of another, as of one family, as brothers and sisters. It taught that relative exaltations, real and fancied superiorities of one over another, so far from freeing us from obligations to the weak or giving us liberty to take advantage of their inferiority, was God’s solemn obligation to do more for them. Christ taught the Law of Power to be that the Superior was in the Divine Kingdom of Love, the natural helper, nurse and servant of the inferior. This of course has not been accepted by the world by whom whole races are overslaughed and whole people stamped to the earth by the haughty foot of power.

offensive

The most offensive part of Christ’s life, said Mr. BEECHER, and that which procured his crucifixion, was the potential teaching of these Christian democratic ideas. We know how the Jews hated and despised the Samaritans, and how, in turn, the Samaritans hated and despised the Jews. It was not left for the Christians of our date to initiate a system of hatred — it was fully as effective then as now. The Jews hated Christ because of his ministration to the poor — not that they would object to helping the poor, but they objected to his way, to the mode by which he taught a philosophy which would overturn hierarchies and compel them to most unwelcome duties. The Jews did not like the idea of everybody else sharing with them the good. They could not bear that the Gentiles should follow Him, and soon their most demoniac element was stirred up, which so worked and fumed until the day of His death. They could not bear to hear preached the doctrine that taught of a common origin and a common destiny, of brotherhood, of duties between classes and peoples, and they hated Him who troubled them.

The history of the nations before the time of Christ finds its parallel in the history of nations since.

Then, to be a stranger was to be a criminal, and a shipwrecked man upon a foreign shore was killed, if not eaten, as a matter of course. Each nation thinks itself by some reason superior to all others. The English despise the French, and the French disdain the English; the Germans think that wisdom will die with them, and in despising the rest of mankind, are met by a reciprocal feeling throughout the world; the British look down upon us Americans, end we rather don’t regard the British with a marked degree of affection. This hatred exists, and men cherish it with jealous and cruel vigilance. Christianity and culture have modified its manifestations somewhat, but the spirit is there yet, and there never was a time when this Christian doctrine of the moral obligation of power was more needed than the present. This conviction of superiority is the source of hatred, contempt, and neglect, or culpable and negligent indifference on the part of the strong and great. The history of nations, and their present attitude, prove this. There are cases of parental love, and of friendship too, where the true doctrine prevails; indeed, the nursery is the exception to the rule, but where else does the law of love prevail, to any great degree?

Particularly is this doctrine needed now, because the whole world is thrown open and brought into contiguity. Great Britain is as near to us to-day as Boston was in the time of the Revolution. We need all men, and they need us. We need the isles of the sea, the Chinese and the Indian, and when our intercourse with them takes effect, this law of love, this doctrine of moral obligation comes into play, and we who neglect or disobey it, do so in the very face of the Almighty himself. We, like all nations, are disposed to do right with our equals; and this again evinces the meanness of men when in power. Had China and Mexico been strong and vigorous nations, would Great Britain have warred about her opium, or we for the sake of Texas?

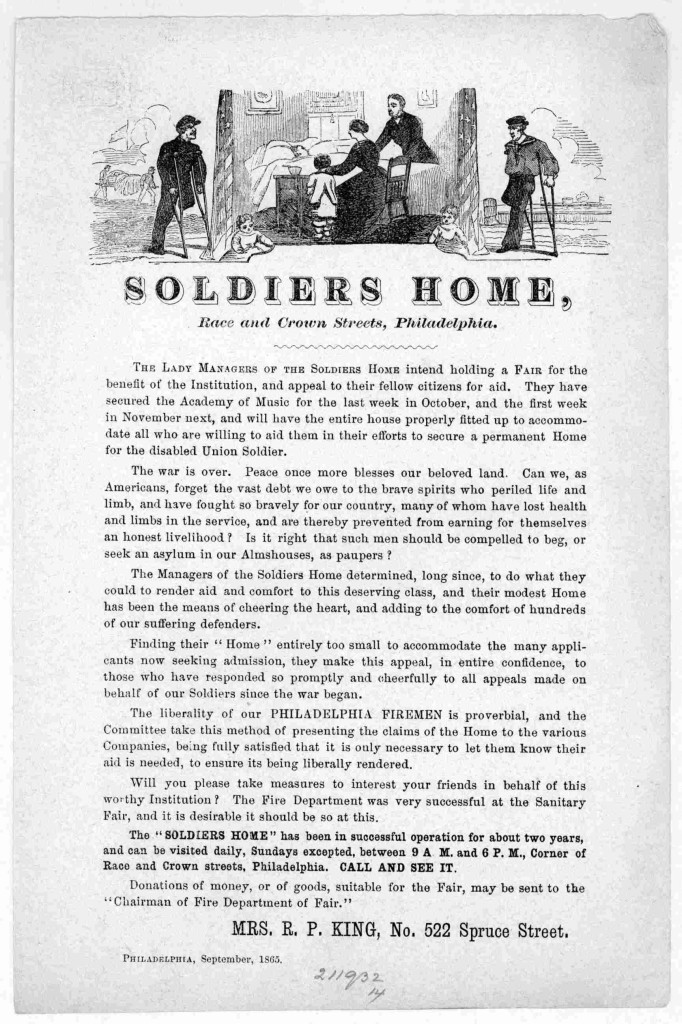

In our own land and time, facts and questions are pressed upon us that demand Christian settlement — settlement on this ground and doctrine. We cannot escape the responsibility. Being strong and powerful, we must nurse, and help, and educate, and foster those who are weak, and poor and ignorant. For my own part, I cannot see how we shall escape the most

TERRIBLE CONFLICT OF CLASSES

by and by, unless we are educated into this doctrine of duty on the part of the superior to the inferior. We are told by zealous and fanatical individuals that all men are equal. We know better. They are not equal. A common brotherhood teaches no such absurdity. A theory of universal physical likeness is no more absurd than this. Now, as in all time, the strong go to the top, the weak to the bottom; its natural and right, and can’t be helped. All branches are not at the top of the tree, but the top does not despise the lower, nor do they all despise the limb or parent trunk, and so in the body politic there must be classes. Some will be at the top and some at the bottom. It is difficult to foresee and estimate the development and POWER of classes in America. They are simply inevitable; they are here now and with be more. If they are friendly, living at peace, loving and respecting and helping one another, all will be well, but if they are selfish, unchristian, if the old Heathen feeling is to reign, each extracting all he can from his neighbor and caring nothing for him, society will be lined by classes as by seams, like batteries, each firing broadside after broadside, the one upon the other. If, on the other hand, the law of love prevails, there will be no ill-will, no envy, no disturbance. Does a child hate his father because he is chief — because he is strong and wise? On the contrary, he grows by his father’s growth, and strengthens with his strength, and if in society there should be fifty grades or classes all helping each other, there would be no trouble, but perfect satisfaction and content.

This Christian doctrine carried into practice will easily settle the most troublesome of our home questions, the

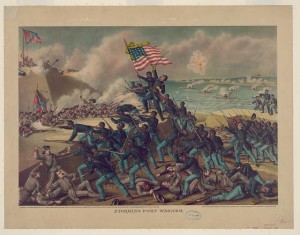

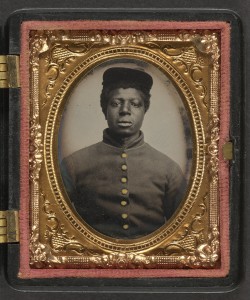

CONDITION OF THE FREEDMEN.

For a hundred years millions of men have suffered every injury that can be inflicted on man, on the ground of their inferiority, as if men’s rights were grounded on power. They have not been permitted their manhood, nor their civil rights, nor could they hold property, nor enjoy the privileges of a citizen, on the ground of their inferiority. Their social relations and family ti[e]s were abolished, their God-inspired feelings crushed, the portal of knowledge sealed on the ground of their infirmity. Nothing else. And on this doctrine, laid down by Christ for apostles and disciples, aye, for himself even, we as a nation have stood ordaining cruelty by law. American slavery is the most accursed of all. It was a most infamous crime. It was taught, not that the superior must help the inferior, but that the inferior must serve the superior. It was taught in the pulpit and administered like doses of ip ecac in the newspapers. It excited no surprise. You rather liked it. You were the stranger, and you persecuted them, and there w[???] [were?] not wanting sober Doctors of Divinity, who, putting on spectacles made by the Divine, diligently searched the Scriptures to see if the New Testament had anything to say against slavery. Of course, they found nothing, and because it was ascertained that Father Abraham, who bought his wife and sold his children, kept a few slaves, it was considered all right for Americans to do the same thing.

Since the emancipation of these poor people, the question of

THEIR PERMANENT CONDITION

comes up for settlement, and it must be settled on right grounds, on Christian grounds, or it wont stay settled. They encounter of course prejudice and distrust on the part of their late masters, but how is it with people outside of the circle of their former owners? Some of you say “God in his wisdom has made it my duty to care for these people, but if in his wisdom he could only put ’em away somewhere, anywhere, only take ’em away, what a relief it would be.” Quite likely; but he won’t take them away, and they are not going away. They are here, and something must be done with them. These grumblers forget that Christ came upon earth to suffer and toil and be humiliated for them; they see no duty in this opportunity; they find nothing but task and toil and trouble.

Having, however, for public good, emancipated four millions of slaves, we cannot let them alone, unless, first we build around them the laws and civil rights. The power that has severed the former relations must provide others. Who will take care of them? The

MASTERS, THE BLACKS OR WE?

The people have effectually settled that proposition, and have determined that the masters shall not longer have anything to do with them. I hold that the North can take care of them, but the so doing would be a violation of the fundamental law of society, which says that every man must take care of himself. Take an army of one million men, to feed and care for them is a work of the greatest magnitude, and yet we have a nation of thirty millions of people, each of whom, takes care of himself very easily. The

GOVERNMENT CAN’T SUPPORT

“Every man who is under the law has a right to assist in framing it”

RIGHT TO VOTE.

Grant that he is not prepared for it. When will he be? How will he become so? Let him try it, as a boy tries his skates; he may tumble once or twice. What if he does, he will learn by the effort. I would give the privilege to everybody, to the Irishman, and to all foreigners who come here to live; although I believe that in a majority of cases the negro would vote more intelligently and conscientiously than they. Its safe to give the privilege to everybody, and then to teach them.

(Mr. BEECHER then entered upon a long and slightly conversational explanation of his views upon the woman question, giving at length and with some humor his opinion as to the right of the fair sex at the ballot-box. It had no connection with the subject under discussion, and our unlimited space precludes its reproduction here.)

No man is fit to be an American statesman who is afraid of American ideas. Liberty is the boon of every man, and it carries with it civil rights and citizenship. In the older countries this idea progresses rapidly. In England the revolution is at hand; in France but one head is between it and reformation, not revolution — the sceptre is no longer the gilded stick in the hand of the monarch, but the little white ballot in the hand of the voter.

We must accept our own ideas. I believe in liberty and universal citizenship, and would give it to all, were they ten millions in number. I protest that this great question must not be kept for settlement, nor left in the hands of parties to be bargained and scrambled over in the race for power, nor to the selfish spirit of commerce, nor to the convenience of those who owned the slaves, nor to the necessary prejudice and the turbulent hatred of the ignorant among us who are blind to the fact that the whole question of their own right and elevation stands on the same ground.

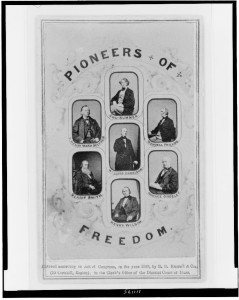

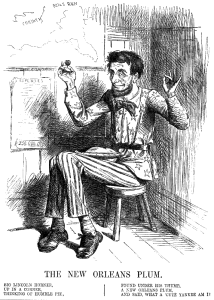

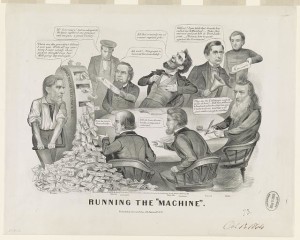

“disturbers of the community and Radicals”(1866, Library of Congress)

No question is settled until it is settled right. We are called disturbers of the community and Radicals. So is the sap in trees; so is spring which heralds the glorious summer. It has pleased God to give us victory on the field of battle. Our late foes are again commingling pleasantly with us, and their leaders, seeing the folly of their course ask pardon and advise a return to peaceful avocations — what more could we ask? Presenting to the world this grand spectacle of might in war, of fraternity in peace, having no turbulent desires for military despotism brooding in the breasts of the thirteen hundred thousand soldiers who but a few weeks since bore our arms, what more fit, what more glorious crown can be given to the column, than the leading up to the status of citizenship the four millions emancipated black men, whose superiors we are, and whose servants in love, in Christ’s example, we should be?

Go then down among the poor and lost, seek them, find them, clothe them with all elements of citizienship, show them the light which you carry, establish and ordain them in liberty, and God shall give you a blessing that neither your children, nor your children’s children shall outlive to the remotest generation.

At the conclusion of the sermon, of which the foregoing is the briefest skeleton, the c[o]ngregation sang a hymn, and were dismissed, with the pastoral benediction.

You can read a racially-motivated opposition to the ideas of Henry Ward Beecher at the Library of Congress. The Black Republican and Office-Holders Journal, apparently published in New York in September 1865, featured “Loyal Nominations” on its front page – “For Mare of New York: Fred Duglas. For Sheriff: Henry Ward Beecher.”

NY Times 9-25-1865

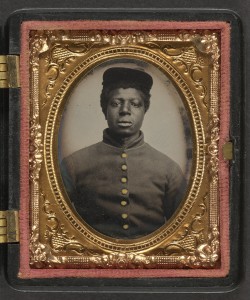

This article did sort of remind me of the pope’s current visit to the USA. The all-caps subtitles didn’t show up in the NY Times’ online archives; I got them from the front page (the above clipping is an example). Images from the Library of Congress: Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, Plymouth Church, Good Samaritan, black soldier, abolitionists

![[Framed photographs of General Ambrose Everett Burnside and Abraham Lincoln with a manuscript signed note in Lincoln's hand.] (M Brady, December 22, 1862 ; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/scsm001051/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/aeb-al-254x300.jpg)

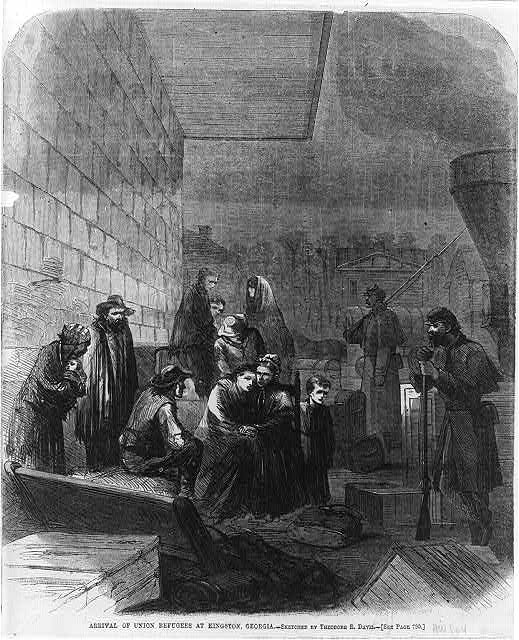

![[Atlanta, Ga. Boxcars with refugees at railroad depot] (1864; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000879/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/03471v-252x300.jpg)

![[Charleston, South Carolina (vicinity).] Steamers at wharf (LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003005353/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/03211v-257x300.jpg)

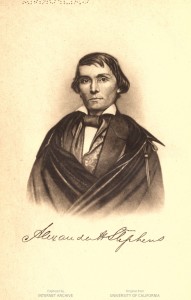

![[Alexander Hamilton Stephens, half-length studio portrait, sitting] / John Goldin & Co. photographers. (between 1860 and 1870); LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2009634258/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/23894v-183x300.jpg)

![[Andrew Johnson, half-length portrait, facing left] / A. Bogardus & Co., 872 B'way, cor. 18th St., N.Y. (New York : A. Bogardus & Co., [between 1865 and 1880]) (LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2004678590/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/3a32470r-183x300.jpg)

![[John Brown, 1800-1859, bust portrait, facing right in memorial frame] (1897; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2005690015/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/3a53020r-235x300.jpg)