Is there not a better future for these men also? The time will come when we shall at least cease to hate them.

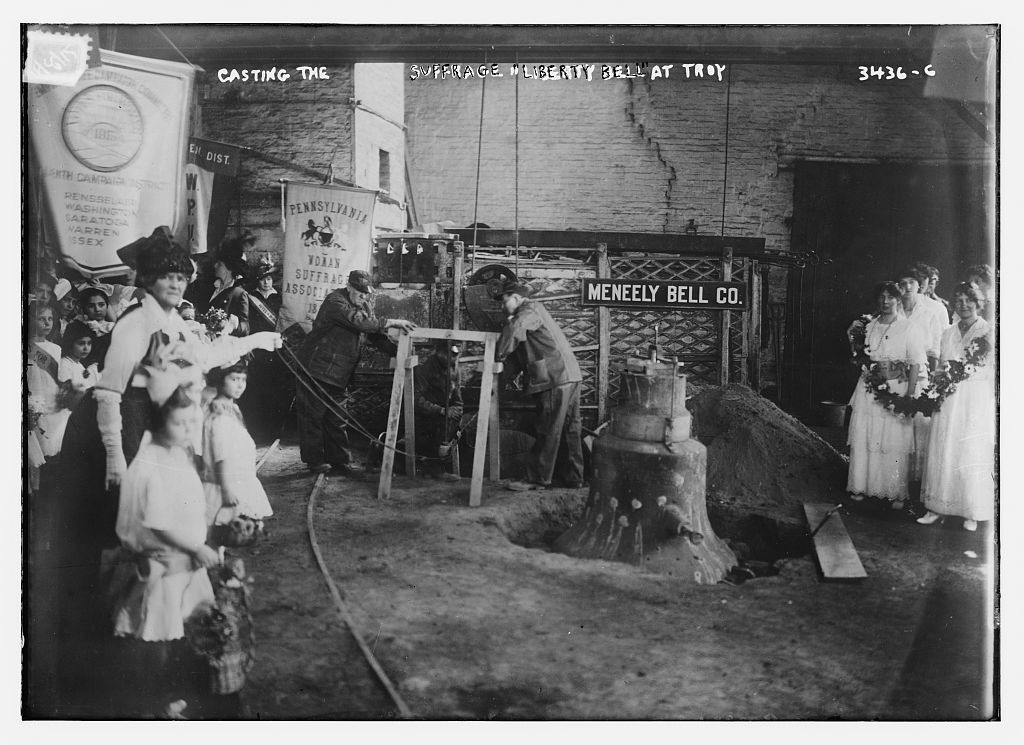

In the summer of 1865 a correspondent visited Gettysburg two years after the great battle. His very long report was published 150 years ago this month. Here are some excerpts focusing mostly on John Lawrence Burns, the War of 1812 veteran who became known as “The hero of Gettysburg” for his actions on July 1, 1863.

From The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVI.—NOVEMBER, 1865.—NO. XCVII.

THE FIELD OF GETTYSBURG.

In the month of August, 1865, I set out to visit some of the scenes of the great conflict through which the country has lately passed. …

From Harrisburg, I went, by the way of York and Hanover, to Gettysburg. Having hastily secured a room at a hotel in the Square, (the citizens call it the “Di’mond,”) I inquired the way to the battle-ground.

“You are on it now,” said the landlord, with proud satisfaction,—for it is not every man that lives, much less keeps a tavern, on the field of a world-famous fight. “I tell you the truth,” said he; and, in proof of his words, (as if the fact were too wonderful to be believed without proof,) he showed me a Rebel shell imbedded in the brick wall of a house close by. (N. B. The battle-field was put into the bill.)

Gettysburg is the capital of Adams County: a town of about three thousand souls,—or fifteen hundred, according to John Burns, who assured me that half the population were Copperheads, and that they had no souls. It is pleasantly situated on the swells of a fine undulating country, drained by the headwaters of the Monocacy. It has no special natural advantages,—owing its existence, probably, to the mere fact that several important roads found it convenient to meet at this point, to which accident also is due its historical renown. The circumstance which made it a burg made it likewise a battle-field.

the “old hero of Gettysburg”

About the town itself there is nothing very interesting. It consists chiefly of two-story houses of wood and brick, in dull rows, with thresholds but little elevated above the street. Rarely a front yard or blooming garden-plot relieves the dreary monotony. Occasionally there is a three-story house, comfortable, no doubt and sufficiently expensive, about which the one thing remarkable is the total absence of taste in its construction. In this respect Gettysburg is but a fair sample of a large class of American towns, the builders of which seem never once to have been conscious that there exists such a thing as beauty.

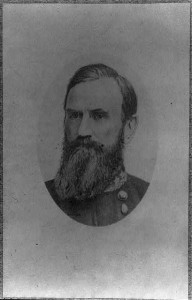

John Burns, known as “the hero of Gettysburg,” was almost the first person whose acquaintance I made. He was sitting under the thick shade of an English elm in front of the tavern. The landlord introduced him as “the old man who took his gun and went into the first day’s fight.” He rose to his feet and received me with sturdy politeness,—his evident delight in the celebrity he enjoys twinkling through the veil of a naturally modest demeanor.

“John will go with you and show you the different parts of the battle-ground,” said the landlord. “Will you, John?”

“Oh, yes, I’ll go,” said John, quite readily; and we set out at once.

A mile south of the town is Cemetery Hill, the head and front of an important ridge, running two miles farther south to Round Top,—the ridge held by General Meade’s army during the great battles. The Rebels attacked on three sides,—on the west, on the north, and on the east; breaking their forces in vain upon this tremendous wedge, of which Cemetery Hill may be considered the point. A portion of Ewell’s Corps had passed through the town several days before, and neglected to secure that very commanding position. Was it mere accident, or something more, which thus gave the key to the country into our hands, and led the invaders, alarmed by Meade’s vigorous pursuit, to fall back and fight the decisive battle here?

With the old “hero” at my side pointing out the various points of interest, I ascended Cemetery Hill. The view from the top is beautiful and striking. On the north and east is spread a finely variegated farm country; on the west, with woods and valleys and sunny slopes between, rise the summits of the Blue Ridge. …

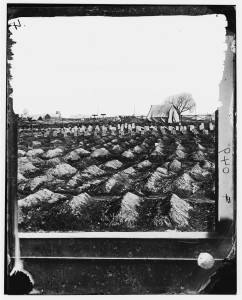

“It don’t look here as it did after the battle,” said John Burns. “Sad work was made with the tombstones. The ground was all covered with dead horses, and broken wagons, and pieces of shells, and battered muskets, and everything of that kind, not to speak of the heaps of dead.” But now the tombstones have been replaced, the neat iron fences have been mostly repaired, and scarcely a vestige of the fight remains. Only the burial-places of the slain are there. Thirty-five hundred and sixty slaughtered Union soldiers lie on the field of Gettysburg. This number does not include those whose bodies have been claimed by friends and removed.

The new cemetery, devoted to the patriot slain, and dedicated with fitting ceremonies on the 19th of November, 1863, adjoins the old one. …

I looked into one of the trenches in which workmen were laying foundations for the headstones, and saw the ends of the coffins protruding. It was silent and dark down there. Side by side the soldiers slept, as side by side they fought. I chose out one coffin from among the rest, and thought of him whose dust it contained,—your brother and mine, although we never knew him. I thought of him as a child, tenderly reared—for this. I thought of his home, his heart-life:—

“Had he a father?

Had he a mother?

Had he a sister?

Had he a brother?

Or was there a nearer one

Still, and a dearer one

Yet, than all other?”

I could not know: in this world, none will ever know. He sleeps with the undistinguishable multitude, and his headstone is lettered, “Unknown.” …

Guided by the sturdy old man, I proceeded first to Culp’s Hill, following a line of breastworks into the woods. Here are seen some of the soldiers’ devices hastily adopted for defence. A rude embankment of stakes and logs and stones, covered with earth, forms the principal work; aside from which you meet with little private breastworks, as it were, consisting of rocks heaped up by the trunk of a tree, or beside a larger rock, or across a cleft in the rocks, where some sharpshooter stood and exercised his skill at his ease. …

Yet here remain more astonishing evidences of fierce fighting than anywhere else about Gettysburg. The trees in certain localities are all seamed, disfigured, and literally dying or dead from their wounds. The marks of balls in some of the trunks are countless. Here are limbs, and yonder are whole tree-tops, cut off by shells. Many of these trees have been hacked for lead, and chips containing bullets have been carried away for relics.

Past the foot of the hill runs Rock Creek, a muddy, sluggish stream, “great for eels,” said John Burns. Big boulders and blocks of stone lie scattered along its bed. Its low shores are covered with thin grass, shaded by the forest-trees. Plenty of Rebel knapsacks and haversacks lie rotting upon the ground; and there are Rebel graves in the woods near by. By these I was inclined to pause longer than John Burns thought it worth the while. I felt a pity for these unhappy men which he could not understand. To him they were dead Rebels, and nothing more; and he spoke with great disgust of an effort which had been made by certain “Copperheads” of the town to have all the buried Rebels, now scattered about in the woods and fields, gathered together in a cemetery near that dedicated to our own dead.

“Yet consider, my friend,” I said, “though they were altogether in the wrong, and their cause was infernal, these, too, were brave men; and under different circumstances, with no better hearts than they had, they might have been lying in honored graves up yonder, instead of being buried in heaps, like dead cattle, down here.”

Is there not a better future for these men also? The time will come when we shall at least cease to hate them.

The cicada was singing, insects were humming in the air, crows were cawing in the tree-tops, the sunshine slept on the boughs or nestled in the beds of brown leaves on the ground,—all so pleasant and so pensive, I could have passed the day there. But John reminded me that night was approaching, and we returned to Gettysburg. …

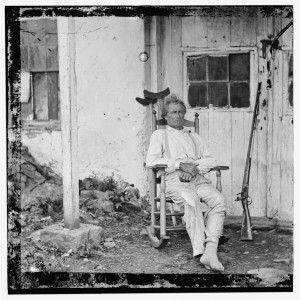

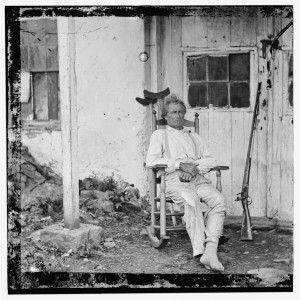

John L. Burns cottage

The next morning, according to agreement, I went to call on the old hero. I found him living in the upper part of a little whitewashed two-story house, on the corner of two streets, west of the town. A flight of wooden steps outside took me to his door. He was there to welcome me. John Burns is a stoutish, slightly bent, hale old man, with a light blue eye, a long, aggressive nose, a firm-set mouth, expressive of determination of character, and a choleric temperament. His hair, originally dark brown, is considerably bleached with age; and his beard, once sandy, covers his face (shaved once or twice a week) with a fine crop of silver stubble. A short, massy kind of man; about five feet four or five inches in height, I should judge. He was never measured but once in his life. That was when he enlisted in the War of 1812. He was then nineteen years old, and stood five feet in his shoes. “But I’ve growed a heap since,” said the old hero.

He introduced me to his wife, a slow, somewhat melancholy old lady, in ill health. “She has been poorly now for a good many years.” They have no children.

At my request he told me his story. He is of Scotch parentage; and who knows but he may be akin to the ploughman-poet whose “arrowy songs still sing in our morning air”? He was born and bred in Burlington, New Jersey. A shoemaker by trade, he became a soldier by choice, and fought the British in what used to be the “last war.” I am afraid he contracted bad habits in the army. For some years after the war he led a wandering and dissipated life. Forty years ago he chanced to find himself in Gettysburg, where he married and settled down. But his unfortunate habits still adhered to him, and he was long looked upon as a man of little worth. At last, however, when there seemed to be no hope of his ever being anything but a despised old man, he took a sudden resolution to reform. The fact that he kept that resolution, and still keeps it so strictly that it is impossible to prevail upon him to taste a drop of intoxicating liquor, attests a truly heroic will. He was afterwards a constable in Gettysburg, in which capacity he served some six years.

On the morning of the first day’s fight he sent his wife away, telling her that he would take care of the house. The firing was near by, over Seminary Ridge. Soon a wounded soldier came into the town and stopped at an old house on the opposite corner. Burns saw the poor fellow lay down his musket, and the inspiration to go into the battle seems then first to have seized him. He went over and demanded the gun.

“What are you going to do with it?” asked the soldier.

“I’m going to shoot some of the damned Rebels!” replied John.

He is not a swearing man, and the strong adjective is to be taken in a strictly literal, not a profane, sense.

Having obtained the gun, he pushed out on the Chambersburg Pike, and was soon in the thick of the skirmish.

“I wore a high-crowned hat, and a long-tailed blue; and I was seventy years old.”

The sight of so old a man, in such costume, rushing fearlessly forward to get a shot in the very front of the battle, of course attracted attention. He fought with the Seventh Wisconsin Regiment, the Colonel of which ordered him back, and questioned him, and finally, seeing the old man’s patriotic determination, gave him a good rifle in place of the musket he had brought with him.

“Are you a good shot?”

“Tolerable good,” said John, who is an old fox-hunter.

“Do you see that Rebel riding yonder?”

“I do.”

“Can you fetch him?”

“I can try.”

The old man took deliberate aim and fired. He does not say he killed the Rebel, but simply that his shot was cheered by the Wisconsin boys, and that afterwards the horse the Rebel rode was seen galloping with an empty saddle. “That’s all I know about it.”

McPherson’s woods – where John L. Burns fought on July 1, 1863

He fought until our forces were driven back in the afternoon. He had already received two slight wounds, and a third one through the arm, to which he paid little attention: “only the blood running down my hand bothered me a heap.” Then, as he was slowly falling back with the rest, he received a final shot through the leg. “Down I went, and the whole Rebel army ran over me.” Helpless, nearly bleeding to death from his wounds, he lay upon the field all night. “About sun-up, next morning, I crawled to a neighbor’s house, and found it full of wounded Rebels.” The neighbor afterwards took him to his own house, which had also been turned into a Rebel hospital. A Rebel surgeon dressed his wounds; and he says he received decent treatment at the hands of the enemy, until a Copperhead woman living opposite “told on him.”

“That’s the old man who said he was going out to shoot some of the damned Rebels!”

Some officers came and questioned him, endeavoring to convict him of “bushwhacking”; but the old man gave them little satisfaction. This was on Friday, the third day of the battle; and he was alone with his wife in the upper part of the house. The Rebels left, and soon after two shots were fired. One bullet entered the window, passed over Burns’s head, and struck the wall behind the lounge on which he was lying. The other shot fell lower, passing through a door. Burns is certain that the design was to assassinate him. That the shots were fired by the Rebels there can be no doubt; and as they were fired from their own side, towards the town, of which they held possession at the time, John’s theory was plainly the true one. The hole in the window, and the bullet-marks in the door and wall remain.

Burns went with me over the ground where the first day’s fight took place. He showed me the scene of his hot day’s work,—pointed out two trees, behind which he and one of the Wisconsin boys stood and “picked off every Rebel[Pg 622] that showed his head,” and the spot where he fell and lay all night under the stars and dew.

This act of daring on the part of so aged a citizen, and his subsequent sufferings from wounds, naturally called out a great deal of sympathy, and caused him to be looked upon as a hero. But a hero, like a prophet, has not all honor in his own country. There’s a wide-spread, violent prejudice against Burns among that class of the townspeople termed “Copperheads.” The young men, especially, who did not take their guns and go into the fight as this old man did, but who ran, when running was possible, in the opposite direction, dislike Burns. Some aver that he did not have a gun in his hand that day, and that he was wounded by accident, happening to get between the two lines. Others admit the fact of his carrying a gun into the fight, but tell you, with a sardonic smile, that his “motives were questionable.” Some, who are eager enough to make money on his picture, sold against his will, and without profit to him, will tell you in confidence, after you have purchased it, that “Burns is a perfect humbug.”

After studying the old man’s character, conversing both with his friends and enemies, and sifting evidence, during four days spent in Gettysburg, I formed my conclusions. Of his going into the fight, and fighting, there is no doubt whatever. Of his bravery, amounting even to rashness, there can be no reasonable question. He is a patriot of the most zealous sort; a hot, impulsive man, who meant what he said, when he started with the gun to go and shoot some of the Rebels qualified with the strong adjective. A thoroughly honest man, too, I think; although some of his remarks are to be taken with considerable allowance. His temper causes him to form immoderate opinions and to make strong statements. “He always goes beyant,” said my landlord, a firm friend of his, speaking of this tendency to overstep the bounds of calm judgment.

“He always goes beyant”

Burns is a sagacious observer of men and things, and makes occasionally such shrewd remarks as this:—

“Whenever you see the marks of shells and bullets on a house all covered up, and painted and plastered over, that’s the house of a Rebel sympathizer; but when you see them all preserved and kept in sight, as something to be proud of, that’s the house of a true Union man.”

Well, whatever is said or thought of the old hero, he is what he is, and has satisfaction in that, and not in other people’s opinions; for so it must finally be with all. Character is the one thing valuable. Reputation, which is a mere shadow of the man, what his character is reputed to be, is, in the long run, of infinitely less importance.

I am happy to add that the old man has been awarded a pension. …

_________________________________________________

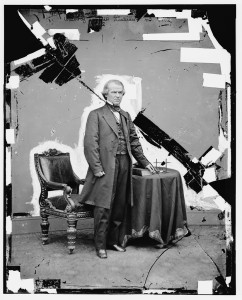

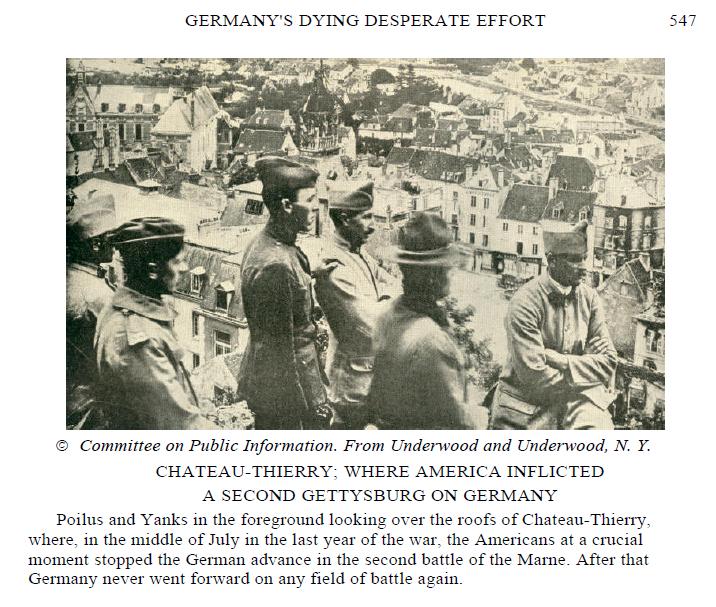

From the Library of Congress: rocking chair; Burns’ home; woods; statue. The Chateau-Thierry photo can be found on page 547 of the pdf version at Project Gutenberg.

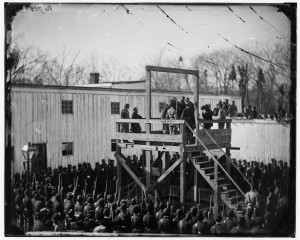

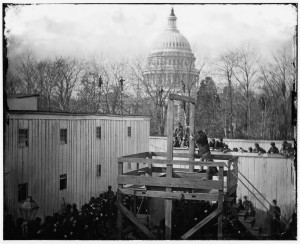

![[Washington, D.C. Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold] (by Alexander Gardner; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003001031/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/04194v-300x244.jpg)