“bounteous, obliging disposition,”

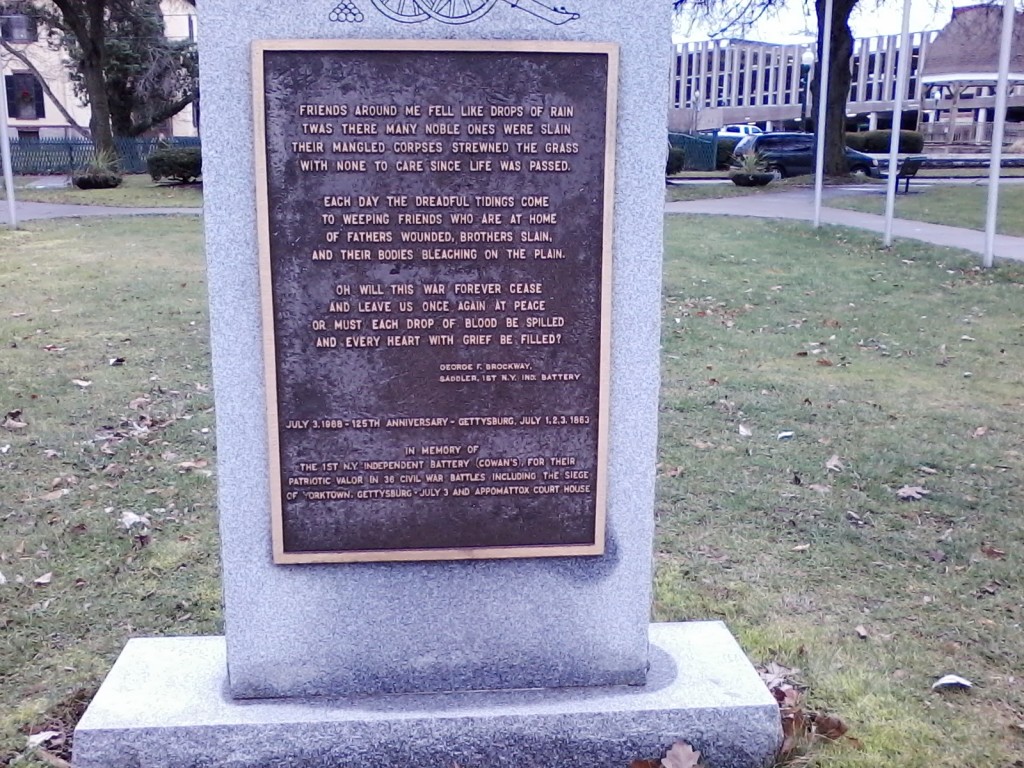

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch December 23, 1865:

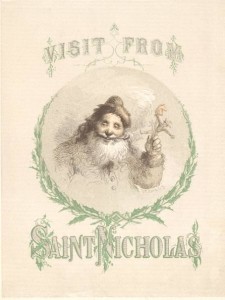

The great problem of Christmas, with all who are not afflicted by the general malady of chronic impecuniousness, is what to buy for a Christmas present. The patron saint, Kriss Kringle, St. Nicholas, or by whatever other name that most charming and amiable of all the saints is known, must find Christmas the most perplexing of all the festivals. We mean no disrespect to the other saints who figure on the church calendar when we bestow upon this one special commendation. But Kriss Kringle or St. Nicholas is the only one of them whose acquaintance we ever made, or who ever visits the earth in a tangible shape. Certainly, if the other canonized persons resemble him in a bounteous, obliging disposition, we should be very glad to be on intimate terms with them all.

“an immensity of stockings to be hung “

There are an immensity of stockings to be hung up Sunday night [December 24, 1865], an illimitable forest of Christmas trees to be planted, and innumerable millions of little children whose hearts are beating wildly at this moment with conjectures of Kriss Kringle’s designs with reference to those stockings and trees. We are not more astonished at the sublime unselfishness and inexhaustible resources of Kriss, than his extraordinary ability to surmount the great difficulty of Christmas– what to buy. Somehow or other, he generally does work out that perplexing problem, and generally to the satisfaction of all concerned. What a deal of time he must spend in studying the shop windows and inspecting the bewildering variety of their attractions! Sometimes, when his funds are low, the good saint must be a sad as well as a puzzled saint, yet he never appears to us more amiable than just then.–To see him trudging along, and trying to make some little children happy, but without the means to do it as he would wish, is a sight that must enlist the sympathy of all his brother saints, and, no doubt, will induce them all, one of these days, to open their purse-strings, and make it even with those little children, who seem to be somewhat neglected now.

After all, the best [ Chritmas ] [sic] gift is the love and affection that prompt the outward tokens and impart value to them, if they are ever so cheap and commonplace. But it ought not to be forgotten by those who have the means to give, that there are many habitations in this city in which no stockings can be hung up, no Christmas tress planted, and whose inmates would be only too happy to obtain the bare means of life. There can be no difficulty in solving the question–what Christmas gift to bestow upon them.

The historical Saint Nicholas lived from March 15, 270 – December 6, 343 in modern day Turkey. He is appropriately a patron saint of children, as well as several other groups of people.

From In God’s Garden Stories of the Saints for Little Children by Amy Steedman:

SAINT NICHOLAS

latter day Saint Nicholas

Of all the saints that little children love is there any to compare with Santa Claus? The very sound of his name has magic in it, and calls up visions of well-filled stockings, with the presents we particularly want peeping over the top, or hanging out at the side, too big to go into the largest sock. Besides, there is something so mysterious and exciting about Santa Claus, for no one seems to have ever seen him. But we picture him to ourselves as an old man with a white beard, whose favourite way of coming into our rooms is down the chimney, bringing gifts for the good children and punishments for the bad.

Yet this Santa Claus, in whose name the presents come to us at Christmas time, is a very real saint, and we can learn a great deal about him, only we must remember that his true name is Saint Nicholas. Perhaps the little children, who used to talk of him long ago, found Saint Nicholas too difficult to say, and so called him their dear Santa Claus. But we learn, as we grow older, that Nicholas is his true name, and that he is a real person who lived long years ago, far away in the East.

The father and mother of Nicholas were noble and very rich, but what they wanted most of all was to have a son. They were Christians, so they prayed to God for many years that he would give them their heart’s desire; and when at last Nicholas was born, they were the happiest people in the world.

They thought there was no one like their boy; and indeed he was wiser and better than most children, and never gave them a moment’s trouble. But alas, while he was still a child, a terrible plague swept over the country, and his father and mother died, leaving him quite alone.

Saint Nicholas as icon

All the great riches which his father had possessed were left to Nicholas, and among other things he inherited three bars of gold. These golden bars were his greatest treasure, and he thought more of them than all the other riches he possessed.

Now in the town where Nicholas lived there dwelt a nobleman with three daughters. They had once been very rich, but great misfortunes had overtaken the father, and now they were all so poor they had scarcely enough to live upon.

At last a day came when there was not even bread enough to eat, and the daughters said to their father:

‘Let us go out into the streets and beg, or do anything to get a little money, that we may not starve.’

But the father answered:

‘Not to-night. I cannot bear to think of it. Wait at least until to-morrow. Something may happen to save my daughters from such disgrace.’

Now, just as they were talking together, Nicholas happened to be passing, and as the window was open he heard all that the poor father said. It seemed terrible to think that a noble family should be so poor and actually in want of bread, and Nicholas tried to plan how it would be possible to help them. He knew they would be much too proud to take money from him, so he had to think of some other way. Then he remembered his golden bars, and that very night he took one of them and went secretly to the nobleman’s house, hoping to give the treasure without letting the father or daughters know who brought it.

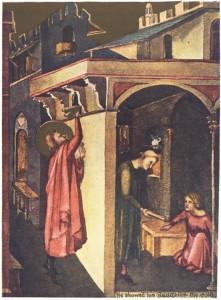

To his joy Nicholas discovered that a little window had been left open, and by standing on tiptoe he could just reach it. So he lifted the golden bar and slipped it through the window, never waiting to hear what became of it, in case any one should see him. (And now do you see the reason why the visits of Santa Claus are so mysterious?)

Inside the house the poor father sat sorrowfully watching, while his children slept. He wondered if there was any hope for them anywhere, and he prayed earnestly that heaven would send help. Suddenly something fell at his feet, and to his amazement and joy, he found it was a bar of pure gold.

‘My child,’ he cried, as he showed his eldest daughter the shining gold, ‘God has heard my prayer and has sent this from heaven. Now we shall have enough and to spare. Call your sisters that we may rejoice together, and I will go instantly and change this treasure.’

in lieu of a chimney … and flying reindeer

The precious golden bar was soon sold to a money-changer, who gave so much for it that the family were able to live in comfort and have all that they needed. And not only was there enough to live upon, but so much was over that the father gave his eldest daughter a large dowry, and very soon she was happily married.

When Nicholas saw how much happiness his golden bar had brought to the poor nobleman, he determined that the second daughter should have a dowry too. So he went as before and found the little window again open, and was able to throw in the second golden bar as he had done the first. This time the father was dreaming happily, and did not find the treasure until he awoke in the morning. Soon afterwards the second daughter had her dowry and was married too.

The father now began to think that, after all, it was not usual for golden bars to fall from heaven, and he wondered if by any chance human hands had placed them in his room. The more he thought of it the stranger it seemed, and he made up his mind to keep watch every night, in case another golden bar should be sent as a portion for his youngest daughter.

And so when Nicholas went the third time and dropped the last bar through the little window, the father came quickly out, and before Nicholas had time to hide, caught him by his cloak.

‘O Nicholas,’ he cried, ‘is it thou who hast helped us in our need? Why didst thou hide thyself?’ And then he fell on his knees and began to kiss the hands that had helped him so graciously.

But Nicholas bade him stand up and give thanks to God instead; warning him to tell no one the story of the golden bars.

This was only one of the many kind acts Nicholas loved to do, and it was no wonder that he was beloved by all who knew him. …

flying reindeer

Clement Clarke Moore’s story sure had taken over the public imagination since its initial anonymous publication in 1823. The image of saint Nicholas as icon is licensed by Creative Commons

Merry Christmas to all!

![Portrait of Ulysses S. Grant (by Alexander Gardner, ca. 1865]; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2004674419/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/3a04853r-224x300.jpg)

![Constitutional Convention, Topeka, Kansas Territory [Topeka] ( Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, vol. 1, no, 1 (1855 Dec. 15), p. 16. ; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/99614006/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/3a10426r-300x222.jpg)

![[Richmond, Va. Ruined buildings in the burned district] (1865; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000656/PP/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/02657v-300x293.jpg)