In a review of a Northern periodical the Richmond Daily Dispatch of December 23, 1865 said visiting yankees ought to be wary of trusting too much in their tour guides:

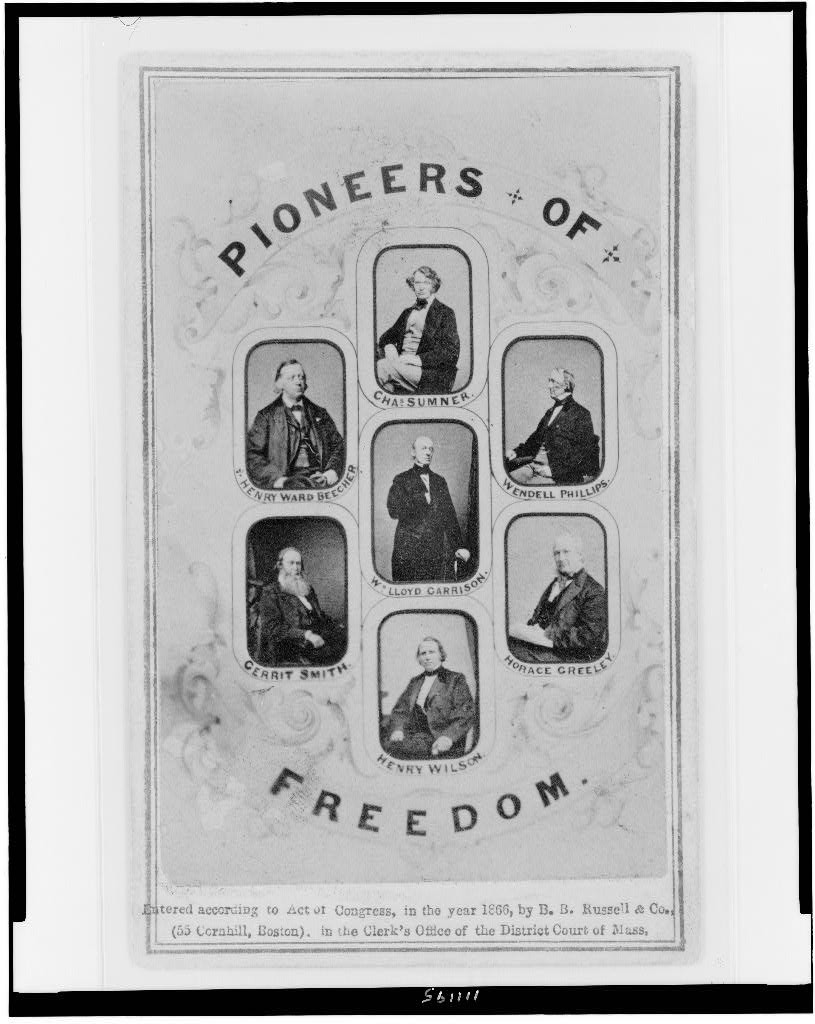

Periodicals.

–The January number of the Atlantic Monthly is upon our table. This is one of the most pretentious, as it is the ablest, of the Northern monthlies. It is the representative of Boston literary taste and talent. Typographically, it is the very neatest, and is from the publishing house of Ticknor & Fields. Of course it partakes of the anti-Southern sentiment, which predominates in the American Athens, and can hardly do justice to the South in any matter relating to National politics. In other respects it is entertaining even here, and maintains a most respectable position in the world of Literature.

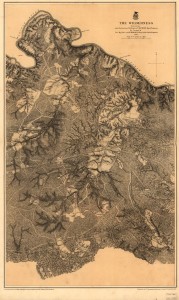

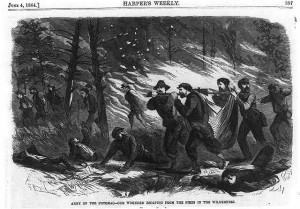

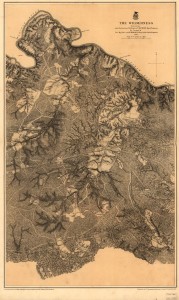

The Wilderness

The present number of the Atlantic offers an inviting bill of fare. One of its articles is a sketch of the battle-field of the Wilderness. The writer was aided in his survey of it by one Elijah, whose poor horse and buggy transported the two from Fredericksburg to the field. The traveler makes an entertaining sketch of the journey. In his statement about the scene of battle, he puts great faith in the stories of his guide, who had been recommended to him as one familiar with the locality. And this reminds us of a story — a true one–which should warn sensation-seekers in battle-fields not to believe every thing that guides tell them. This story is as follows:

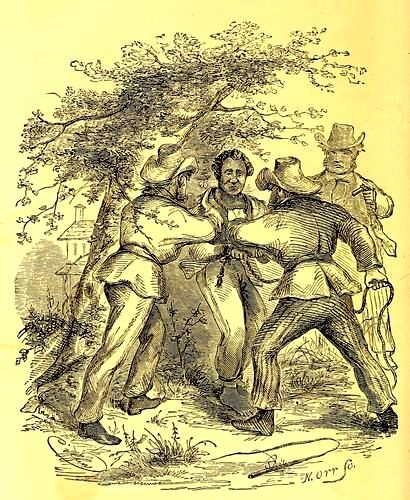

A Confederate General recently met an Irishman who had served gallantly under him in the war. He was seated on the box of a hack, wielding the whip over a pair of horses that had not been over-fed. Hailing him, and interchanging expressions of mutual satisfaction at meeting, the General inquired: “And how are you getting along, Pat?”

“Finely, General,” said he. “I took to this business immediately [ after ] the evacuation, and I have made twenty dollars a day by visiting the battle-fields. You know, General, I know nothing about them, yet I take travelers to them, and talk as if I know’d everything. I took a party of Bostonians the other day to the Sivin Pines, and showed the hottest part of the fight. I saw a pile of bones in the midst of it that belonged to some animal or other, and pointing to them, said: “There lay the bones of the vilest rebel Gineral that fell in the fight. You think, Gineral, they didn’t believe it, and each of them put a piece of the bones in his carpet-bag to take home wid him?”

Well, to sensation-hunters and writers it matters very little whether they get the truth or not. The fiction is better than fact, if the fiction is the more startling of the two. So we commend Pat to all of this class — he will be sure to give them capital for a thrilling narrative. …

Much of the Atlantic article is a description of the journey from Fredericksburg to the Wilderness battlefield. Even the Yankee author knew he had to take his guide’s information with a grain of salt. Elijah got McLaws confused with Magruder. (page 41). As the duo neared the Wilderness the author reflected on General Grant’s approach to the battles against General Lee’s army in the spring of 1864:

… The Battle of Bull Run in 1861, Pope’s campaign, and Burnside’s defeat at Fredericksburg in 1862, and, lastly, Hooker’s unsuccessful attempt at Chancellorsville in the spring of 1863, had shown how hard a road to Richmond this was to travel. Repeatedly, as we tried it and failed, the hopes of the Confederacy rose exultant; the heart of the North sank as often, heavy with despair. McClellan’s Peninsular route had resulted still more fatally. We all remember the anguish and anxiety of those days. But the heart of the North shook off its despair, listened to no timid counsels; it was growing fierce and obdurate. We no longer received the news of defeat with cries of dismay, with teeth close-set, a smile upon the quivering lips, and a burning fire within. Had the Rebels triumphed again? Then so much the worse for them! Had we been once more repulsed with slaughter from their strong line of defences? Was the precious blood poured out before them all in vain? At last it should not be in vain! Though it should cost a new thirty years’ war and a generation of lives, the red work we had begun must be completed; ultimate failure was impossible, ultimate triumph certain.

![[Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in military uniform] / M.B. Brady & Co. National Photographic Portrait Galleries, No. 352 Pennsylvania Av., Washington, D.C. & New York. (1865; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2013648326/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/35588v-187x300.jpg)

no hesitating, no higgling

We were approaching the scene of Grant’s first great blow aimed at the gates of the Rebel capital. On the field of Chancellorsville you already tread the borders of the field of the Wilderness,—if that can be called a field which is a mere interminable forest, slashed here and there with roads.

Passing straight along the plank road, we came to a large farm-house, which had been gutted by soldiers, and but recently reoccupied. It was still in a scarcely habitable condition. However, we managed to obtain, what we stood greatly in need of, a cup of cold water. I observed that it tasted strongly of iron.

“The reason of that is, we took twelve camp-kettles out of the well,” said the man of the house, “and nobody knows how many more there are down there.”

into the wilderness (Locust Grove in center)

The place is known as Locust Grove. In the edge of the forest, but a little farther on, is the Wilderness Church,—a square framed building, which showed marks of such usage as every uninhabited house receives at the hands of a wild soldiery. Red Mars has little respect for the temples of the Prince of Peace.

“Many a time have I been to meet’n’ in that shell, and sot on hard benches, and heard long sermons!” said Elijah. “But I reckon it’ll be a long while befo’e them doo’s are darkened by a congregation ag’in. Thar a’n’t the population through hyer thar used to be. Oncet we’d have met a hundred wagons on this road go’n’ to market; but I count we ha’n’t met mo’e ‘n a dozen to-day.”

“Wilderness Church ” (Library of Congress)

Not far beyond the church we approached two tall guide-posts erected where the road forks. The one on the right pointed the way to the “Wilderness National Cemetery, No. 1, 4 miles,” by the Orange Court-House turnpike. The other indicated the “Wilderness National Cemetery, No. 2,” by the plank road.

“All this has been done since I was this way,” said Elijah.

We kept the plank road,—or rather the clay road beside it, which stretched before us dim in the hollows, and red as brick on the hillsides. We passed some old fields, and entered the great Wilderness,—a high and dry country, thickly overgrown with dwarfish timber, chiefly scrub oaks, pines, and cedars. Poles lashed to trees for tent-supports indicated where our regiments had encamped; and soon we came upon abundant evidences of a great battle. Heavy breastworks thrown up on Brock’s cross-road, planks from the plank road piled up and lashed against trees in the woods, to form a shelter for our pickets, knapsacks, haversacks, pieces of clothing, fragments of harness, tin plates, canteens, some pierced with balls, fragments of shells, with here and there a round-shot, or a shell unexploded, straps, buckles, cartridge-boxes, socks, old shoes, rotting letters, desolate tracts of perforated and broken trees,—all these signs, and others sadder still, remained to tell their silent story of the great fight of the Wilderness.

A cloud passed over the sun: all the scene became sombre, and hushed with a strange brooding stillness, broken only by the noise of twigs crackling under my feet, and distant growls of thunder. A shadow fell upon my heart also, as from the wing of the Death-Angel, as I wandered through the woods, meditating upon what I saw. Where were the feet that wore those empty shoes? Where was he whose proud waist was buckled in that belt? Some soldier’s heart was made happy by that poor, soiled, tattered, illegible letter, which rain and mildew have not spared; some mother’s, sister’s, wife’s, or sweetheart’s hand, doubtless, penned it; it is the broken end of a thread which unwinds a whole life-history, could we but follow it rightly. Where is that soldier now? Did he fall in the fight, and does his home know him no more? Has the poor wife or stricken mother wailed long for the answer to that letter, which never came, and will never come? And this cap, cut in two by a shot, and stiff with a strange incrustation,—a small cap, a mere boy’s, it seems,—where now the fair head and wavy hair that wore it? O mother and sisters at home, do you still mourn for your drummer-boy? Has the story reached you,—how he went into the fight to carry off his wounded comrades, and so lost his life for their sakes?—for so I imagine the tale which will never be told.

And what more appalling spectacle is this? In the cover of thick woods, the unburied remains of two soldiers,—two skeletons side by side, two skulls almost touching each other, like the cheeks of sleepers! I came upon them unawares as I picked my way among the scrub oaks. I knew that scores of such sights could be seen here a few weeks before; but the United States Government had sent to have its unburied dead collected together in the two national cemeteries of the Wilderness; and I had hoped the work was faithfully done.

“They was No’th-Carolinians; that’s why they didn’t bury ’em,” said Elijah, after a careful examination of the buttons fallen from the rotted clothing.

The ground where they lay had been fought over repeatedly, and the dead of both sides had fallen there. The buttons may, therefore, have told a true story: North-Carolinians they may have been: yet I could not believe that the true reason why they had not been decently interred. It must have been that these bodies, and others we found afterwards, were overlooked by the party sent to construct the cemeteries. It was shameful negligence, to say the least.

The cemetery was near by,—a little clearing in the woods by the roadside, thirty yards square, surrounded by a picket-fence, and comprising seventy trenches, each containing the remains of I know not how many dead. Each trench was marked with a headboard, inscribed with the invariable words,—

“Unknown United States soldiers, killed May, 1864.”

Elijah, to whom I read the Inscription, said, pertinently, that the words, United States soldiers indicated plainly that it had not been the intention to bury Rebels there. No doubt: but these might at least have been buried in the woods where they fell.

As a grim sarcasm on this neglect, somebody had flung three human skulls, picked up in the woods, over the paling, into the cemetery, where they lay blanching among the graves.

Close by the southeast corner of the fence were three or four Rebel graves, with old headboards. Elijah called my attention to them, and wished me to read what the headboards said. The main fact indicated was, that those buried there were North-Carolinians. Elijah considered this somehow corroborative of his theory derived from the buttons. The graves were shallow, and the settling of the earth over the bodies had left the feet of one of the poor fellows sticking out.

The shadows which darkened the woods, and the ominous thunder-growls, culminated in a shower. Elijah crawled under his wagon; I sought the shelter of a tree: the horse champed his fodder, and we ate our luncheon. How quietly upon the leaves, how softly upon the graves of the cemetery, fell the perpendicular rain! The clouds parted, and a burst of sunlight smote the Wilderness; the rain still poured, but every drop was illumined, and I seemed standing in a shower of silver meteors.

The rain over and luncheon finished, I looked about for some solace to my palate after the dry sandwiches, moistened only by the drippings from the tree,—seeking a dessert in the Wilderness. Summer grapes hung their just ripened clusters from the vine-laden saplings, and the chincapin bushes were starred with opening burrs. I followed a woodland path, embowered with the glistening boughs, and plucked, and ate, and mused. The ground was level, and singularly free from the accumulations of twigs, branches, and old leaves, with which forests usually abound. I noticed, however, many charred sticks and half-burnt roots and logs. Then the terrible recollection overtook me: these were the woods that were on fire during the battle. I called Elijah.

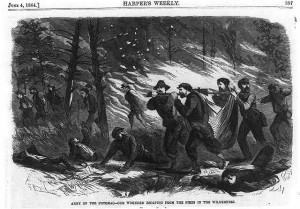

“Army of the Potomac – Our wounded escaping from the fires in the Wilderness ” Library of Congress”

“Yes, all this was a flame of fire while the fight was go’n’ on. It was full of dead and wounded men. Cook and Stevens, farmers over hyer, men I know, heard the screams of the poor fellahs burnin’ up, and come and dragged many a one out of the fire, and laid ’em in the road.”

The woods were full of Rebel graves, with here and there a heap of half-covered bones, where several of the dead had been hurriedly buried together.

I had seen enough. We returned to the cemetery. Elijah hitched up his horse, and we drove back along the plank road, cheered by a rainbow which spanned the Wilderness and moved its bright arch onward over Chancellorsville towards Fredericksburg, brightening and fading, and brightening still again, like the hope which gladdened the nation’s eye after Grant’s victory.

Hal Jespersen’s map of the battle is licensed by Creative Commons

![[Abraham Lincoln] (1890; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2009630138/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/19588v-620x1024.jpg)

![[Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in military uniform] / M.B. Brady & Co. National Photographic Portrait Galleries, No. 352 Pennsylvania Av., Washington, D.C. & New York. (1865; LOC: http://www.loc.gov/item/2013648326/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/35588v-187x300.jpg)