![Group of Negros on their way to the cotton field, St. Helena Is. [i.e. Island], S.C. (Photograph shows freedmen on the Marion Chaplin Plantation on St. Helena Island, South Carolina.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015646735/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1s03948v-1024x520.jpg)

“Group of Negros on their way to the cotton field, St. Helena Is. [i.e. Island], S.C.” – Library of Congress

It was pitiful enough to find so much idleness, but it was more pitiful to observe that it was likely to continue indefinitely. The war will not have borne proper fruit, if our peace does not speedily bring respect for labor, as well as respect for man.

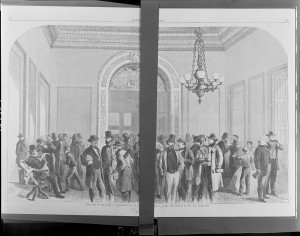

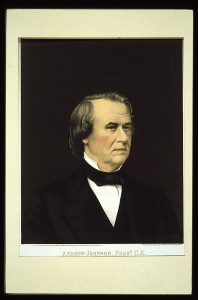

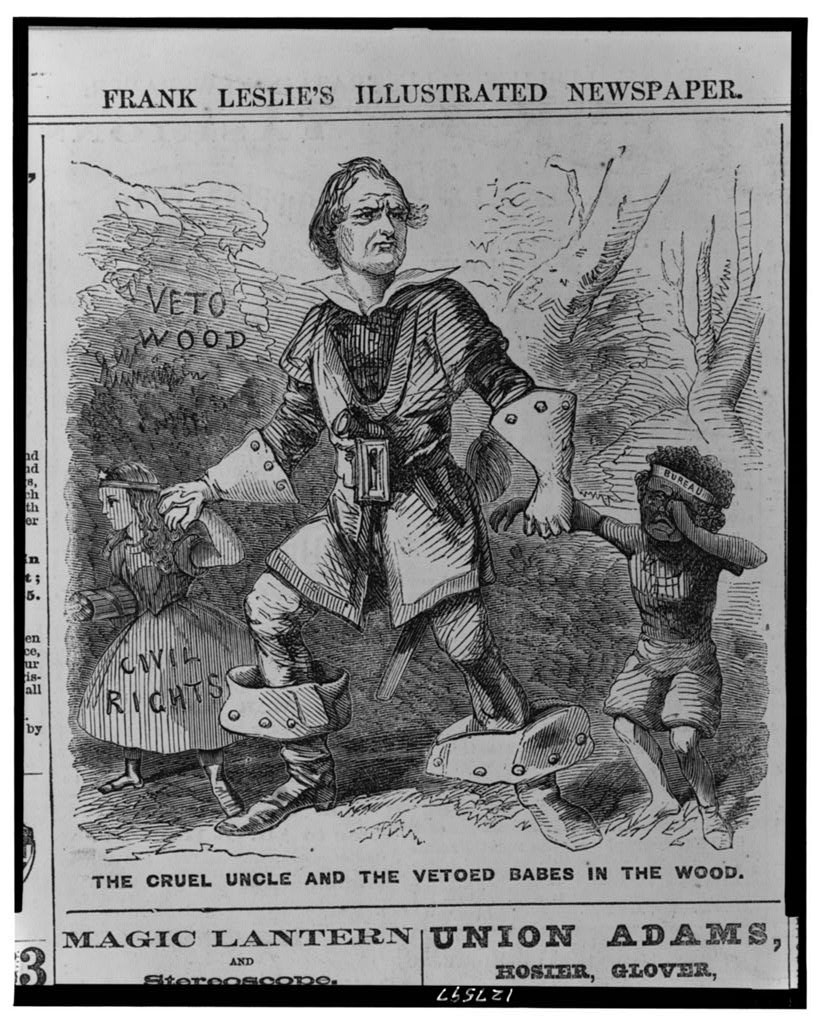

One of President Andrew Johnson’s objections to the Freedmen Bureau extension bill was that the Bureau would allow freedmen to rely on outside help for their survival: “The idea on which the slaves were assisted to freedom was that, on becoming free, they would be a self-sustaining population. Any legislation that shall imply that they are not expected to attain a self-sustaining condition must have a tendency injurious alike to their character and their prospects.” In the fall of 1865 a correspondent from Massachusetts spent three months in three Southern states. He found plenty of idle freedmen. but he tried to understand why this was and discovered that it wasn’t just the blacks – whites were just as likely to shirk work. The following is about the last third of the long report.

![City of Atlanta, Ga., no. 1 / Photo from nature by G. N. Barnard. ([1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008679857/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/18960v-300x233.jpg)

“Illustration showing the destroyed Atlanta roundhouse, with steam engines and train cars in place but with collapsed stone walls.” – Library of Congress

From The Atlantic Monthly, VOL. XVII.—FEBRUARY, 1866—NO. C.:

THREE MONTHS AMONG THE RECONSTRUCTIONISTS.

I spent the months of September, October, and November, 1865, in the States of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. I travelled over more than half the stage and railway routes therein, visited a considerable number of towns and cities in each State, attended the so-called reconstruction conventions at Raleigh, Columbia, and Milledgeville, and had much conversation with many individuals of nearly all classes.

I.

I was generally treated with civility, and occasionally with courteous cordiality. I judge, from the stories told me by various persons, that my reception was, on the whole, something better than that accorded to the majority of Northern men travelling in that section. Yet at one town in South Carolina, when I sought accommodations for two or three days at a boarding-house, I was asked by the woman in charge, “Are you a Yankee or a Southerner?” and when I answered, “Oh, a Yankee, of course,” she responded, “No Yankee stops in this house!” and turned her back upon me and walked off. …

[the end of section III.]

The really bad feature of the situation with respect to the relations of these States to the General Government is, that there is not only very little loyalty in their people, but a great deal of stubborn antagonism, and some deliberate defiance. Further war in the field I do not deem among the possibilities. Be the leaders never so bloodthirsty, the common people have had enough of fighting. The bastard Unionism of North Carolina, the haughty and self-complacent State pride of South Carolina, the arrogant dogmatism and insolent assumption of Georgia,—how shall we build nationality on such foundations? That is the true plan of reconstruction which makes haste very slowly. It does not comport with the character of our Government to exact pledges of any State which are not exacted of all. The one sole needful condition is, that each State establish a republican form of government, whereby all civil rights at least shall be assured in their fullest extent to every citizen. The Union is no Union, unless there is equality of privileges among the States. When Georgia and the Carolinas establish this republican form of government, they will have brought themselves into harmony with the national will, and may justly demand readmission to their former political relations in the Union. Each State has some citizens, who, wiser than the great majority, comprehend the meaning of Southern defeat with praiseworthy insight. Seeing only individuals of this small class, a traveller might honestly conclude that the States were ready for self-government. Let not the nation commit the terrible mistake of acting on this conclusion. These men are the little leaven in the gross body politic of Southern communities. It is no time for passion or bitterness, and it does not become our manhood to do anything for revenge. Let us have peace and kindly feeling; yet, that our peace may be no sham or shallow affair, it is painfully essential that we keep these States awhile within national control, in order to aid the few wise and just men therein who are fighting the great fight with stubborn prejudice and hidebound custom. Any plan of reconstruction is wrong which accepts forced submission as genuine loyalty, or even as cheerful acquiescence in the national desire and purpose.

IV

Before the war, we heard continually of the love of the master for his slave, and the love of the slave for his master. There was also much talk to the effect that the negro lived in the midst of pleasant surroundings, and had no desire to change his situation. It was asserted that he delighted in a state of dependence, and throve on the universal favor of the whites. Some of this language we conjectured might be extravagant; but to the single fact that there was universal good-will between the two classes every Southern white person bore evidence. So, too, in my late visit to Georgia and the Carolinas, they generally seemed anxious to convince me that the blacks had behaved well during the war,—had kept at their old tasks, had labored cheerfully and faithfully, had shown no disposition to lawlessness, and had rarely been guilty of acts of violence, even in sections where there were many women and children, and but few white men.

Yet I found everywhere now the most direct antagonism between the two classes. The whites charge generally that the negro is idle, and at the bottom of all local disturbances, and credit him with most of the vices and very few of the virtues of humanity. The negroes charge that the whites are revengeful, and intend to cheat the laboring class at every opportunity, and credit them with neither good purposes nor kindly hearts. This present and positive hostility of each class to the other is a fact that will sorely perplex any Northern man travelling in either of these States. One would say, that, if there had formerly been such pleasant relations between them, there ought now to be mutual sympathy and forbearance, instead of mutual distrust and antagonism. One would say, too, that self-interest, the common interest of capital and labor, ought to keep them in harmony; while the fact is, that this very interest appears to put them in an attitude of partial defiance toward each other. I believe the most charitable traveller must come to the conclusion, that the professed love of the whites for the blacks was mostly a monstrous sham or a downright false pretence. For myself, I judge that it was nothing less than an arrant humbug.

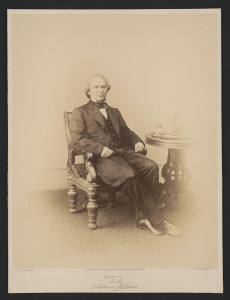

“‘Zion’ school for colored children, Charleston, South Carolina / from a sketch by A.R. Waud.” – Library of Congress

The negro is no model of virtue or manliness. He loves idleness, he has little conception of right and wrong, and he is improvident to the last degree of childishness. He is a creature,—as some of our own people will do well to keep carefully in mind,—he is a creature just forcibly released from slavery. The havoc of war has filled his heart with confused longings, and his ears with confused sounds of rights and privileges: it must be the nation’s duty, for it cannot be left wholly to his late master, to help him to a clear understanding of these rights and privileges, and also to lay upon him a knowledge of his responsibilities. He is anxious to learn, and is very tractable in respect to minor matters; but we shall need almost infinite patience with him, for he comes very slowly to moral comprehensions.

Going into the States where I went,—and perhaps the fact is true also of the other Southern States,—going into Georgia and the Carolinas, and not keeping in mind the facts of yesterday, any man would almost be justified in concluding that the end and purpose in respect to this poor negro was his extermination. It is proclaimed everywhere that he will not work, that he cannot take care of himself, that he is a nuisance to society, that he lives by stealing, and that he is sure to die in a few months; and, truth to tell, the great body of the people, though one must not say intentionally, are doing all they well can to make these assertions true. If it is not said that any considerable number wantonly abuse and outrage him, it must be said that they manifest a barbarous indifference to his fate, which just as surely drives him on to destruction as open cruelty would.

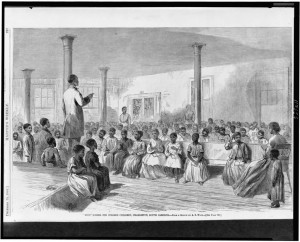

“Cotton team in North Carolina” – Library of Congress

There are some men and a few women—and perhaps the number of these is greater than we of the North generally suppose—who really desire that the negro should now have his full rights as a human being. With the same proportion of this class of persons in a community of Northern constitution, it might be justly concluded that the whole community would soon join or acquiesce in the effort to secure for him at least a fair share of those rights. Unfortunately, however, in these Southern communities the opinion of such persons cannot have such weight as it would in ours. The spirit of caste, of which I have already spoken, is an element figuring largely against them in any contest involving principle,—an element of whose practical workings we here know very little. The walls between individuals and classes are so high and broad, that the men and women who recognize the negro’s rights and privileges as a freeman are almost as far from the masses as we of the North are. Moreover, that any opinion savors of the “Yankee”—in other words, is new to the South—is a fact that even prevents its consideration by the great body of the people. Their inherent antagonism to everything from the North—an antagonism fostered and cunningly cultivated for half a century by the politicians in the interest of Slavery—is something that no traveller can photograph, that no Northern man can understand, till he sees it with his own eyes, hears it with his own ears, and feels it by his own consciousness. That the full freedom of the negroes would be acknowledged at once is something we had no warrant for expecting. The old masters grant them nothing, except at the requirement of the nation,—as a military and political necessity; and any plan of reconstruction is wrong which proposes at once or in the immediate future to substitute free-will for this necessity.

Three fourths of the people assume that the negro will not labor, except on compulsion; and the whole struggle between the whites on the one hand and the blacks on the other hand is a struggle for and against compulsion. The negro insists, very blindly perhaps, that he shall be free to come and go as he pleases; the white insists that he shall come and go only at the pleasure of his employer. The whites seem wholly unable to comprehend that freedom for the negro means the same thing as freedom for them. They readily enough admit that the Government has made him free, but appear to believe that they still have the right to exercise over him the old control. It is partly their misfortune, and not wholly their fault, that they cannot understand the national intent, as expressed in the Emancipation Proclamation and the Constitutional Amendment. I did not anywhere find a man who could see that laws should be applicable to all persons alike; and hence even the best men hold that each State must have a negro code. They acknowledge the overthrow of the special servitude of man to man, but seek through these codes to establish the general servitude of man to the commonwealth. I had much talk with intelligent gentlemen in various sections, and particularly with such as I met during the conventions at Columbia and Milledgeville, upon this subject, and found such a state of feeling as warrants little hope that the present generation of negroes will see the day in which their race shall be amenable only to such laws as apply to the whites.

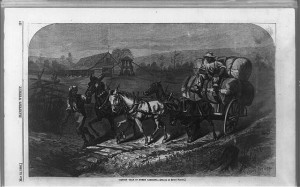

“Plowing in South Carolina / from a sketch by Jas. E. Taylor.” – Library of Congress

I think the freedmen divide themselves into four classes: one fourth recognizing; very clearly, the necessity of work, and going about it with cheerful diligence and wise forethought; one fourth comprehending that there must be labor, but needing considerable encouragement to follow it steadily; one fourth preferring idleness, but not specially averse to doing some job-work about the towns and cities; and one fourth avoiding labor as much as possible, and living by voluntary charity, persistent begging, or systematic pilfering. It is true, that thousands of the aggregate body of this people appear to have hoped, and perhaps believed, that freedom meant idleness; true, too, that thousands are drifting about the country or loafing about the centres of population in a state of vagabondage. Yet of the hundreds with whom I talked, I found less than a score who seemed beyond hope of reformation. It is a cruel slander to say that the race will not work, except on compulsion. I made much inquiry, wherever I went, of great numbers of planters and other employers, and found but very few cases in which it appeared that they had refused to labor reasonably well, when fairly treated and justly paid. Grudgingly admitted to any of the natural rights of man, despised alike by Unionists and Secessionists, wantonly outraged by many and meanly cheated by more of the old planters, receiving a hundred cuffs for one helping hand and a thousand curses for one kindly word,—they bear themselves toward their former masters very much as white men and women would under the same circumstances. True, by such deportment they unquestionably harm themselves; but consider of how little value life is from their stand-point. They grope in the darkness of this transition period, and rarely find any sure stay for the weary arm and the fainting heart. Their souls are filled with a great, but vague longing for freedom; they battle blindly with fate and circumstance for the unseen and uncomprehended, and seem to find every man’s hand raised against them. What wonder that they fill the land with restlessness!

![City of Atlanta, Ga., no. 2 / Photo from nature by G. N. Barnard. ([1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008679858/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/18961v-300x233.jpg)

“Illustration showing a street corner in Atlanta with a destroyed bank building, intact neighboring buildings and shops, and covered wagons.” – Library of Congress

However unfavorable this exhibit of the negroes in respect to labor may appear, it is quite as good as can be made for the whites. I everywhere found a condition of affairs in this regard that astounded me. Idleness, not occupation, seemed the normal state. It is the boast of men and women alike, that they have never done an hour’s work. The public mind is thoroughly debauched, and the general conscience is lifeless as the grave. I met hundreds of hale and vigorous young men who unblushingly owned to me that they had not earned a penny since the war closed. Nine tenths of the people must be taught that labor is even not debasing. It was pitiful enough to find so much idleness, but it was more pitiful to observe that it was likely to continue indefinitely. The war will not have borne proper fruit, if our peace does not speedily bring respect for labor, as well as respect for man. When we have secured one of these things, we shall have gone far toward securing the other; and when we have secured both, then indeed shall we have noble cause for glorying in our country,—true warrant for exulting that our flag floats over no slave.

Meantime, while we patiently and helpfully wait for the day in which

“All men’s good shall

Be each man’s rule, and Universal Peace

Lie like a shaft of light across the land,”

there are at least five things for the nation to do; make haste slowly in the work of reconstruction; temper justice with mercy, but see to it that justice is not overborne; keep military control of these lately rebellious States, till they guaranty a republican form of government; scrutinize carefully the personal fitness of the men chosen therefrom as representatives in the Congress of the United States; and sustain therein some agency that shall stand between the whites and the blacks, and aid each class in coming to a proper understanding of its privileges and responsibilities.

![Freedom on the plantation ([Charleston, S.C.?] : [publisher not identified], [between 1863 and 1866]; LOC: v)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1s03989v-1024x532.jpg)

“Freedom on the plantation” – Library of Congress

![Capt. B.D. Foulois and Lieut. J.E. [or J.C.?] Carberry picked up by Mexican along road [in wagon] after their aeroplane had fallen 1500 feet - Mexican-U.S. Campaign after Villa, 1916 (c1916 April 27; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2002699808/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/3b24490r.jpg)

![Untitled. [I've Had About Enough of This] (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/306154)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/canvas.png)

![[Two unidentified soldiers in Union private's uniforms sitting next to table with cannon ball on top; one soldier has an amputated leg and holds crutches] (between 1861 and 1865; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2012648229/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/33443v-300x241.jpg)

![Group of Negros on their way to the cotton field, St. Helena Is. [i.e. Island], S.C. (Photograph shows freedmen on the Marion Chaplin Plantation on St. Helena Island, South Carolina.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015646735/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1s03948v-1024x520.jpg)

![City of Atlanta, Ga., no. 1 / Photo from nature by G. N. Barnard. ([1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008679857/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/18960v-300x233.jpg)

![City of Atlanta, Ga., no. 2 / Photo from nature by G. N. Barnard. ([1866]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008679858/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/18961v-300x233.jpg)

![Freedom on the plantation ([Charleston, S.C.?] : [publisher not identified], [between 1863 and 1866]; LOC: v)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1s03989v-1024x532.jpg)

![[Horace] Greeley statue, Tribune Office (between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2005019292/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/19303v-703x1024.jpg)