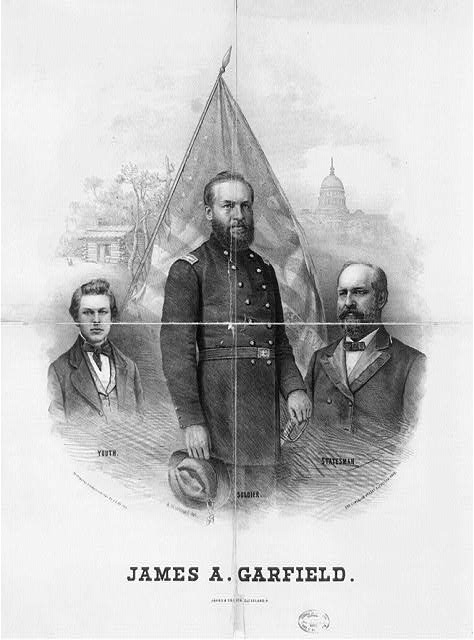

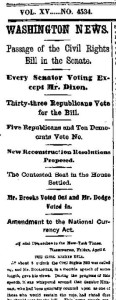

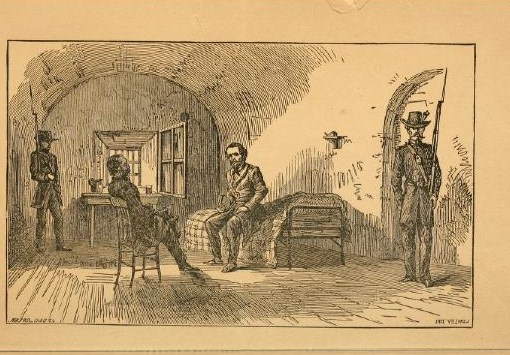

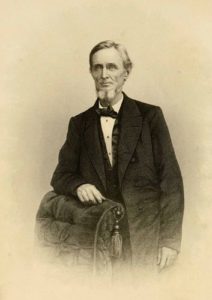

After former Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured by Union troops on May 10, 1865 near Irwinville, Georgia, he was imprisoned at Fort Monroe for two years from May 22, 1865. Initially Mr. Davis was confined to a casemate at Fort Monroe and investigated as a possible co-conspirator in the assassination of President Lincoln. He was ill during the first several months of his confinement. Eventually Mr. Davis was moved to a bigger room in the fort, his health gradually improved, and his wife moved in. “In May 1866, his wife, Varina Howell Davis, took up permanent residence at Fort Monroe.” (Encyclopedia Virginia). It was reported by The New-York Times that 150 years ago today (see cutting to right) Mrs. Davis visited President Johnson to request that the Fort Monroe authorities take better care of her husband. The president informed her that her husband was already allowed freedom of movement within the fort and the attending surgeon would be consulted for questions of proper care.

After it became clear that Jefferson Davis was not implicated in the Lincoln assassination, he was still charged with treason. The May 19, 1866 issue The New-York Times reported that either the House or Senate Judiciary Committee found there was insufficient evidence to support the charge that “JEFF. DAVIS is guilty of complicity in the assassination of Mr. LINCOLN.” The May 15, 1866 issue of the Times headlined that the treason trial was scheduled for June.

Here’s a bit about the imprisonment from Frank H. Alfriend’s sympathetic The Life of Jefferson Davis (1868; from page 640):

Next came the atrocious proclamation charging Mr. Davis with complicity in the assassination of President Lincoln. It is safe to say that incidents hitherto prominent by their infamy, will be forgotten by history, in comparison with the dastardly criminal intent which instigated that document. Circumstances warrant the belief that not one of the conspirators against the life and honor of Mr. Davis, believed either then or now, that the charge had one atom of truth. Had the charge been honestly made, it would have been disavowed, when its falsity became apparent. But this would not have subserved the end of the conspirators, and the poison was permitted to circulate and rankle, long after the calumny had been exploded during the investigations of the military commission, in the cases of Mrs. Surratt and Captain Wirz. At length justice was vindicated by the publication of the confidential correspondence between Holt and Conover, which disclosed the unparalleled subornation and perjury upon which the conspirators relied. Well has it been said that the world will yet wonder “how it was that a people, passing for civilized and Christian, should have consigned Jefferson Davis to a cell, while they tolerated Edwin M. Stanton as a Cabinet Minister.”

We have no desire to dwell upon the details of Mr. Davis’ long and cruel imprisonment. The story is one over which the South has wept tears of agony, at whose recital the civilized world revolted, and which, in years to come, will mantle with shame the cheek of every American citizen who values the good name of his country. In a time of profound peace, when the last vestige of resistance to Federal authority had disappeared in the South, Mr. Davis, wrecked in fortune and in health, in violation of every fundamental principle of American liberty, of justice and humanity, was detained for two years, without trial, in close confinement, and, during a large portion of this period, treated with all the rigor of a sentenced convict.

But if indeed Mr. Davis was thus to be prejudged as the “traitor” and “conspirator” which the Stantons, and Holts, and Forneys declared him to be, why should he be selected from the millions of his advisers and followers, voluntary participants in his assumed “treason,” as the single victim of cruelty, outrage, and indignity? What is there in his antecedents inconsistent with the character of a patriotic statesman devoted to the promotion of union, fraternity, harmony, and faithful allegiance to the Constitution and laws of his country? We have endeavored faithfully to trace his distinguished career as a statesman and soldier, and at no stage of his life is there to be found, either in his conduct or declared opinions, the evidence of infidelity to the Union as its character and objects were revealed to his understanding. Nor is there to be found in his personal character any support of that moral turpitude which a thousand oracles of falsehood have declared to have peculiarly characterized his commission of “treason.”

No tongue and pen were more eloquent than his in describing the grandeur, glory, and blessings of the Union, and in invoking for its perpetuation the aspirations and prayers of his fellow-citizens. In the midst of passion and tumult, in 1861, he was conspicuous by his zeal for compromise, and for a pacific solution of difficulties. No Southern Senator abandoned his seat with so pathetic and regretful an announcement of the necessity which compelled the step. …

Jefferson Davis remained imprisoned until May 1867. On March 4, 1868 “The U.S. government files in federal court its final indictment against former Confederate president Jefferson Davis on charges of treason. The trial is further delayed because of the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.” On February 15, 1869 “U.S. Attorney enters “nolle prosequi” into the record for United States v. Jefferson Davis, thus ending the case.” (Encyclopedia Virginia)

![[2 views] (1) Banking-House, Denver City, Colorado - miners bringing in gold dust [interior]; (2) The Overland Coach Office, Denver City, Colorado [street scene] (Harper's Weekly, January 27, 1866 p.27; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2006675494/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/3b01677r-213x300.jpg)

![Daisies gathered for Decoration Day, May 30, 1899] (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2001703674/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/3a07937v-1024x823.jpg)

![Mourning badge of colored satin with portrait of Lincoln]. Assassinated at Washington 14 April 1865. I have said nothing but what I am willing to live by. And if it be the pleasure of almighty god to die by. A. Lincoln (LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000482/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/ALmourning-badge-76x300.jpg)