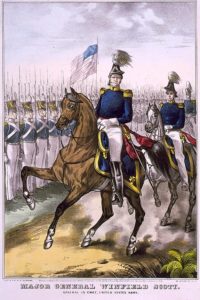

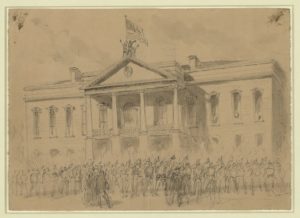

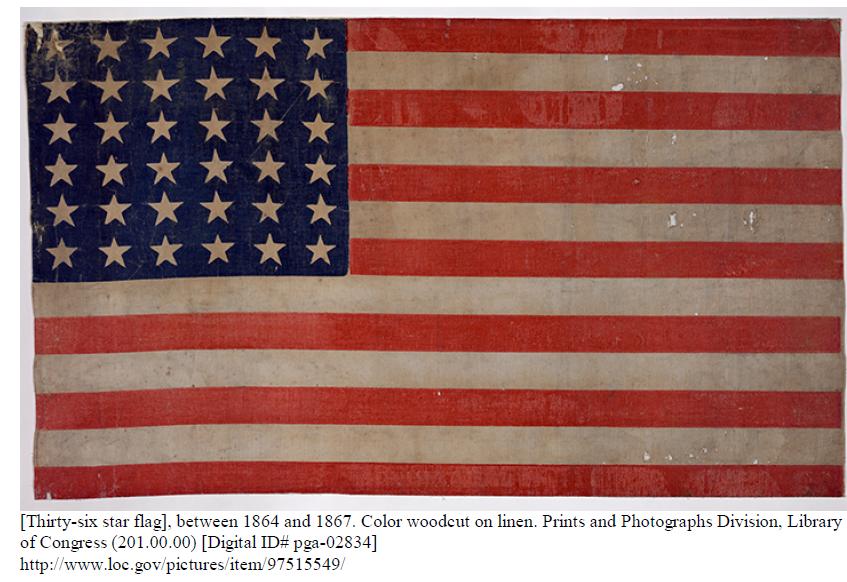

“Battle of Ridgeway, C.W.”

150 years ago today an army of Fenians, Irish-Americans who wanted Great Britain to let Ireland become an independent republic, attacked Canadian forces at the Battle of Ridgeway. “The Fenian insurgents [were] led by Brigadier General John O’Neill, a former Union cavalry commander who had specialized in anti-guerrilla warfare in Ohio.” Although the Fenians won the battle, they scampered back across the Niagara River when they realized large British and Canadian reinforcements were on the way, which “convinced many of the Fenians to return in haste to the United States – some on logs, on rafts, or by swimming. O’Neill and 850 Fenians surrendered their arms to waiting U.S. authorities.”

From Ridgeway: An Historical Romance of the Fenian Invasion of Canada by Scian Dubh (I have no idea how authentic the following report is)

AUTHENTIC REPORT OF THE INVASION OF CANADA, AND THE BATTLE OF RIDGEWAY,

By the Army of the Irish Republic, under General O’NEILL, June, 1866.

About midnight, on the 31st May, the men commenced moving from Buffalo to Lower Black Rock, about three miles down the river, and at 3:30 A.M., on the 1st of June, all of the men, with the arms and ammunition, were on board four canal boats, and towed across the Niagara River, to a point on the Canadian side called Waterloo, and at 4 o’clock A.M., the Irish flag was planted on British soil, by Colonel Starr, who had command of the first two boats.

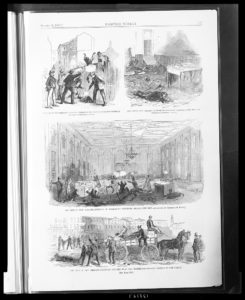

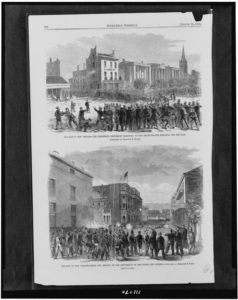

NY Times June 3, 1866

On landing, O’Neill immediately ordered the telegraph wires leading from the town to be cut down; and sent a party to destroy the railroad bridge leading to Port Colborne.

Colonel Starr, in command of the Kentucky and Indiana troops, proceeded through the town of Fort Erie to the old Fort, some three miles distant up the river, and occupied it for a short time, hoisting the Irish flag.

O’Neill then waited on the Reeve of Fort Erie, and requested him to see some of the citizens of the place, and have them furnish rations for the men, at the same time assuring him that no depredations on the citizens would be permitted, as he had come to drive out British authority from the soil, and not for the purpose of pillaging the citizens. The request for provisions was cheerfully complied with.

About 10 o’clock A.M., he moved into camp on Newbiggin’s Farm, situated on Frenchman’s Creek, four miles down the river from Fort Erie, where he remained till 10 o’clock P.M.

During the afternoon, Capt. Donohue, of the 18th, while out in command of a foraging party, on the road leading to Chippewa, came up with the enemy’s scouts, who fled at his approach.

Later in the afternoon, Col. Hoy was sent with one hundred men in the same road. He also came up with some scouts about six miles from camp. Here he was ordered to halt.

an independent-minded lass

By this time—8 o’clock P.M.—information was received that a large force of the enemy, said to be five thousand strong, with artillery, were advancing in two columns; one from the direction of Chippewa, and the other from Port Colborne; also, that troops from Port Colborne were to make an attack from the lake side.

Here truth compels me to make an admission that I would fain have kept from the public. Some of the men who crossed over with us the night before, managed to leave the command during the day, and recross to Buffalo, while others remained in houses around Fort Erie. This I record to their lasting disgrace.

On account of this shameful desertion, and the fact that arms had been sent out for eight hundred men, O’Neill had to destroy three hundred stand, to prevent them falling into the bands of the enemy. At this time he could not depend on more than five hundred men, about one-tenth of the reputed number of the enemy, which he knew were surrounding him. Rather a critical position, but he had been sent to accomplish a certain object, and he was determined to accomplish it.

At 10 o’clock P.M., he broke camp, and marched towards Chippewa, and at midnight changed direction, and moved on the Limestone Ridge road, leading toward Ridgeway; halting a few hours on the way to rest the men;—this for the purpose of meeting the column advancing from Port Colborne. His object was to get between the two columns, and, if possible, defeat one of them before the other could come to its assistance.

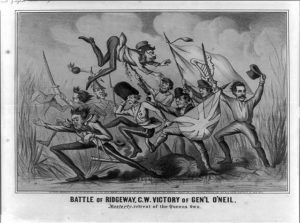

fleeing Canadians

At about 7 o’clock A.M., 2d of June, when within three miles of Ridgeway, Col. Owen Starr in command of the advanced guard, came up with the advance of the enemy, mounted, and drove them some distance, till he got within sight of their skirmish line, which extended on both sides of the road about half a mile. By this time, O’Neill could hear the whistle of the railroad cars which brought the enemy from Port Colborne. He immediately advanced his skirmishers, and formed line of battle behind temporary breastworks made of rails, on a road leading to Fort Erie, and running parallel with the enemy’s line. The skirmishing was kept up over half an hour, when, perceiving the enemy flanking him on both aides, and not being able to draw out their centre, which was partially protected by thick timber, befell back a few hundred yards, and formed a new line. The enemy seeing he had only a few men—about four hundred—and supposing that he had commenced a retreat, advanced rapidly in pursuit. When they got close enough, he gave them a volley, and then charged them, driving them nearly three miles, through the town of Ridgeway. In their hasty retreat they threw away knapsacks, guns, and everything that was likely to retard their speed, and left some ten or twelve killed and twenty-five or thirty wounded, with twelve prisoners, in his hands. Amongst the killed was Lieut. McEachern, and amongst the wounded Lieut. Ruth, both of the “Queen’s Own.” The pursuit was given up about a mile beyond Ridgeway.

fleeing Fenians (NY Times June 4, 1866)

Although he had met and defeated the enemy, yet his position was still a very critical one. The reputed strength of the enemy engaged in the fight was fourteen hundred, composed of the “Queen’s Own,” the 13th Hamilton Battalion, and other troops. A regiment which had left Fort Colburne was said to be on the road to reinforce them. He also knew that the column from Chippewa would hear of the fight, and in all probability move up in his rear.

Thus situated, and not knowing what was going on elsewhere, he decided that his best policy was to return to Fort Erie, and ascertain if crossings had been made at other points, and if so, he was willing to sacrifice himself and his noble little command, for the sake of leaving the way open, as he felt satisfied that a large proportion of the enemy’s forces had been concentrated against him.

He collected a few of his own wounded, and put them in wagons, and for want of transportation had to leave six others in charge of the citizens, who promised to look after them and bury the dead of both sides. He then divided his command, and sent one half, under Col. Starr, down the railroad, to destroy it and burn the bridges, and with the other half took the pike road leading to Fort Erie. Col. Starr got to the old Fort about the same time that he himself did to the village of Fort Erie, 4 o’clock P.M. He (Starr) left the men there under the command of Lieut. Col. Spaulding, and joined O’Neill in a skirmish with a company of the Welland Battery, which had arrived there from Port Colborne in the morning, and which picked up a few of the men who had straggled from the command the day before. They had these men prisoners on board the steamer “Robb.” The skirmish lasted about fifteen minutes, the enemy firing from the houses. Three or four were killed, and some eight or ten wounded, on each side.

It was here that Lieut. Col. Bailey was wounded, while gallantly leading the advance on this side of the town. Here forty-five of the enemy were taken prisoners, among them Capt. King, who was wounded, (leg since amputated,) Lieut. McDonald, Royal Navy, and Commander of the steamer “Robb,” and Lieut. Nemo, Royal Artillery. O’Neill then collected his men, and posted Lieut. Col. Grace, with one hundred men, on the outskirts of the town, guarding the road leading to Chippewa, while with the remainder of the command he proceeded to the old Fort.

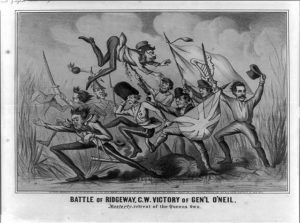

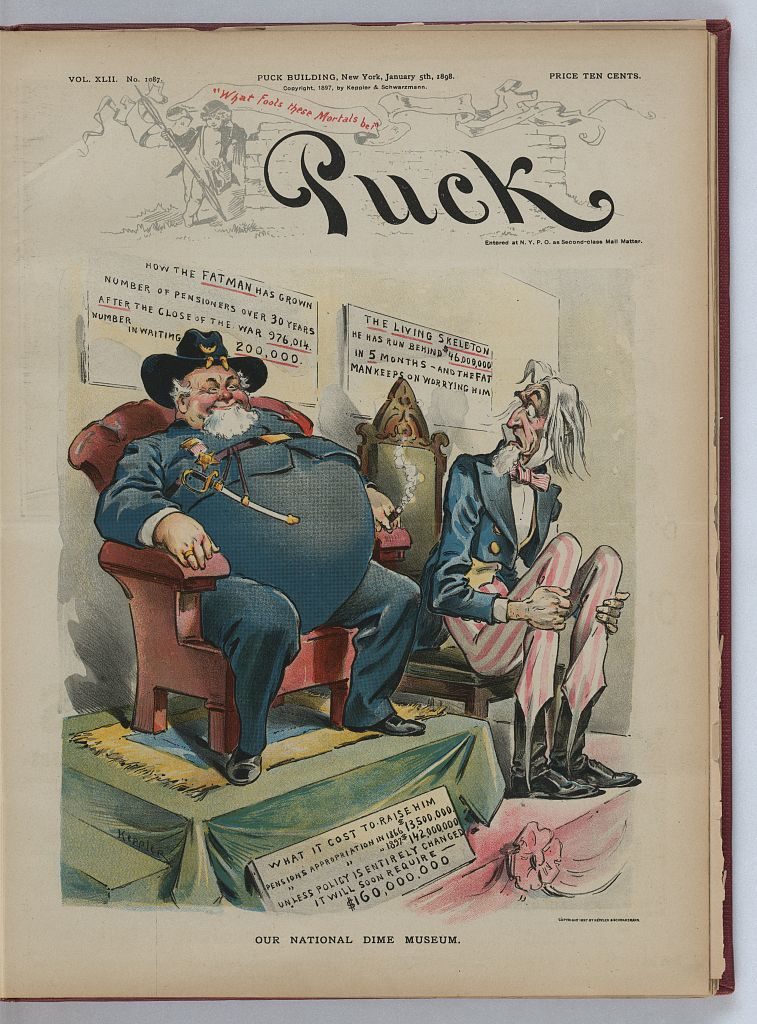

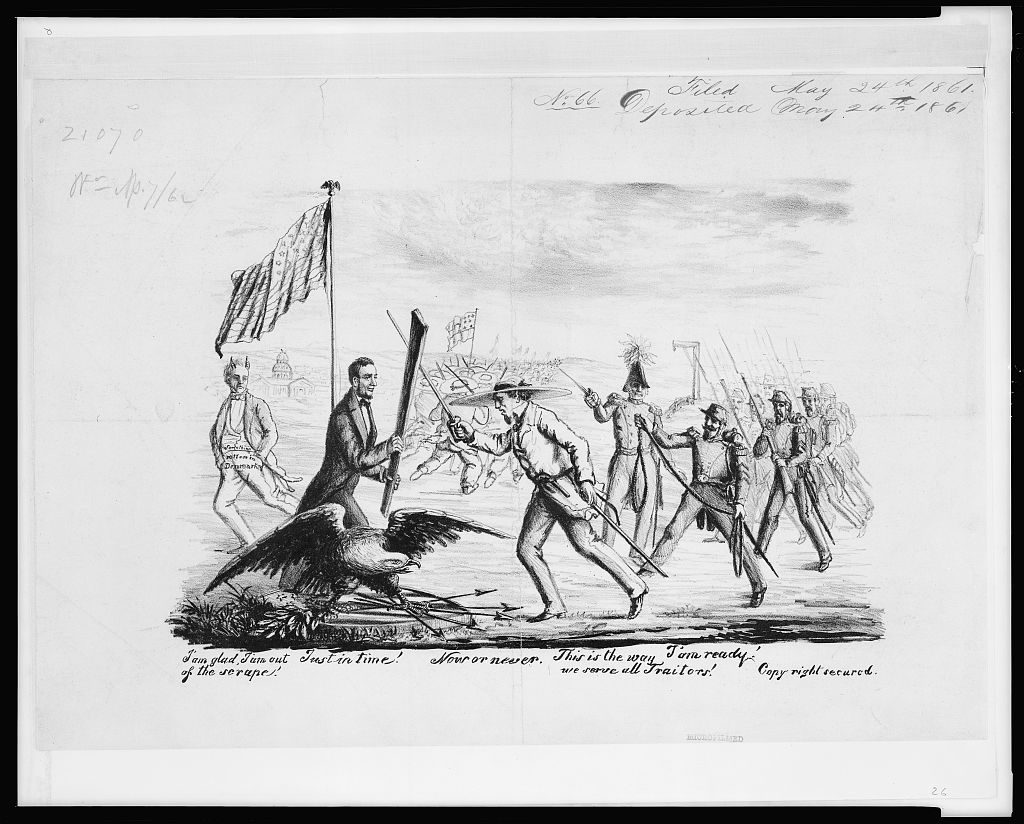

General Meade vs. Fenians

About six o’clock A.M., he sent word to Capt. Hynes and his friends at Buffalo that the enemy could surround him before morning with five thousand men, fully provided with artillery, and that his little command, which had by this time considerably decreased, could not hold out long, but that if a movement was going on elsewhere, he was perfectly willing to make the Old Fort a slaughter pen, which he knew it would be the next day if he remained. FOR HE WOULD NEVER HAVE SURRENDERED.

Many of the men had not a mouthful to eat since Friday morning, and none of them had eaten anything since the night before, and all after marching forty miles and fighting two battles, though the last could only properly be called a skirmish. They were completely worn out with hunger and fatigue.

On receiving information that no crossing had been effected elsewhere, he sent word to have transportation furnished immediately; and about ten o’clock P.M. Capt. Hynes came from Buffalo and informed him that arrangements had been made to recross the river.

Previous to this time some of the officers and men, realizing the danger of their position, availed themselves of small boats and recrossed the river, but the greater portion remained until the transportation arrived, which was about 12 o’clock on the night of June 2, and about 2 o’clock A.M. on the morning of the 3d, all except a few wounded men were safely on board a large scow attached to a tug boat which hauled into American waters. Here they were hailed by the tug Harrison, belonging to the U.S. steamer Michigan, having on board one 12-pounder pivot gun, which fired across their bows and threatened to sink them unless they hauled to and surrendered. With this request they complied; not because they feared the 12-pounder, or the still more powerful guns of the Michigan, which lay close by, but because they respected the authority of the United States, in defence of which many of them had fought and bled during the late war. They would have as readily surrendered to an infant bearing the authority of the Union, as to Acting Master Morris of the tug Harrison, who is himself an Englishman. The number thus surrendered was three hundred and seventeen men, including officers.

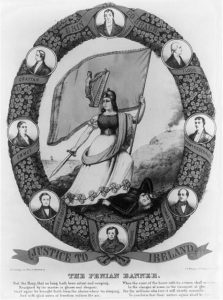

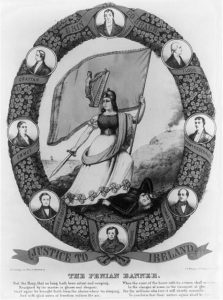

The Fenian banner

The officers were taken on board the Michigan, and were well treated by Capt Bryson and the gentlemanly officers of his ship, while the men were kept on the open scow, which was very filthy, without any accommodation whatever, and barely large enough for them to turn round in. Part of the time the rain poured down on them in torrents. I am not certain who is to blame for this cruel treatment; but whoever the guilty parties are they should be loathed and despised by all men. The men were kept on board the scow for four days and then discharged on their own recognizances to appear at Canandaigna [probably Canandaigua] on the 19th of June, to answer to the charge of having violated the Neutrality Laws. The officers were admitted to bail. The report generally circulated, and, I might say, generally believed, that the pickets were left behind, and that they were captured by the enemy, is entirely false. Every man who remained with the command, excepting a few wounded, had the same chance of escaping that O’Neill himself had.

To the extraordinary exertions of our friends of Buffalo, F.B. Gallagher, Wm. Burk, Hugh Mooney, James Whelan, Capt. James Doyle, John Conners, Edward Frawley, James J. Crawley, M.T. Lynch, James Cronin, and Michael Donahue, the command were indebted for being able to escape from the Canadian side. Col. H.R. Stagg and Capt. McConvey, of Buffalo, were also very assiduous in doing everything in their power. Col. Stagg had started from Buffalo with about two hundred and fifty men, to reinforce O’Neill, but the number was too small to be of any use, and he was ordered to return. Much praise is due to Drs. Trowbridge and Blanchard, of Buffalo, and Surgeon Donnelly, of Pittsburg, for their untiring attendance to the wounded.

All who were with the command acted their parts so nobly that I feel a little delicacy in making special mention of any, and shall not do so except in two instances: One is Michael Cochrane, Color Sergeant of the Indianapolis Company, whose gallantry and daring were conspicuous throughout the fight at Ridgeway. He was seriously wounded, and fell into the hands of the enemy. The other is Major John C. Canty, who lived at Fort Erie. He risked everything he possessed on earth, and acted his part gallantly in the field.

In the fight at Ridgeway, and the skirmish at Fort Erie, as near as can be ascertained, the Fenian loss was eight killed and fifteen wounded. Among the killed was Lieut. E.R. Lonergan, a brave young officer, of Buffalo. Of the enemy, thirty were killed and one hundred wounded.

You can get a ton of information about the battle, including maps and Peter Vronsky’s book here. The New-York Times headlined the Fenian raid from June 2- June 10 and had a lot of fun with the Fenians and the “F” alliteration. HistoryNet provides a good summary.

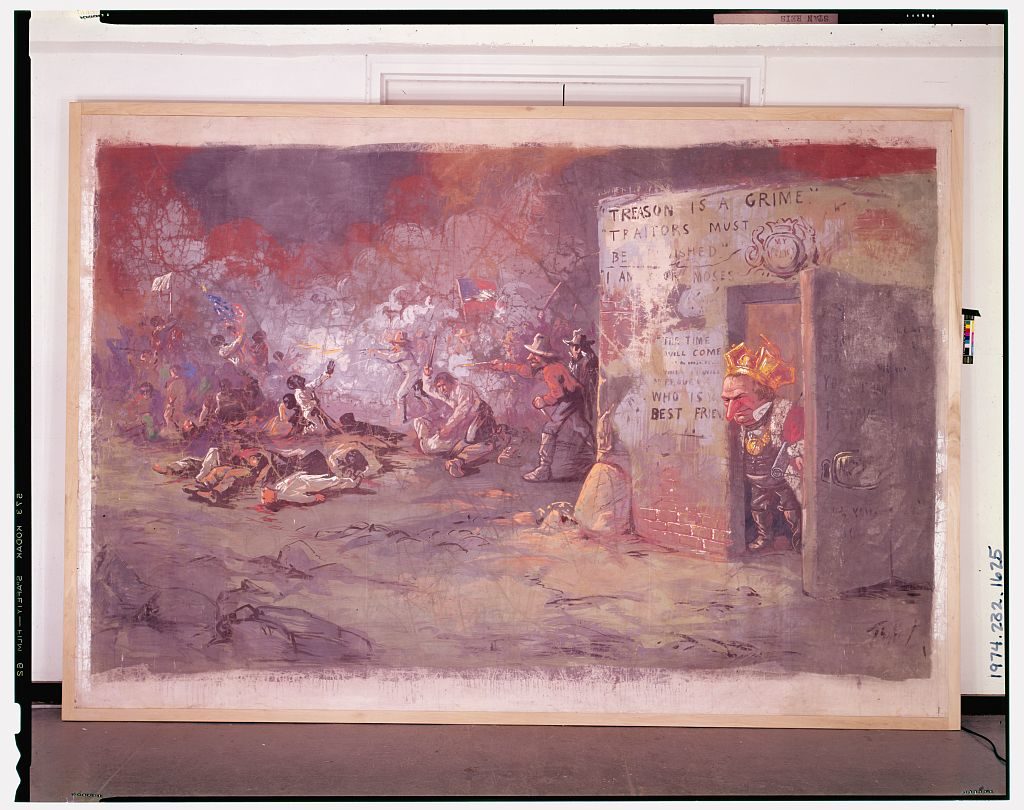

From the Library of Congress: Red Green (the Wikipedia link up top mentions that the Canadian units involved wore either British red or a dark-green; the Fenians wore old Civil War uniforms with green facings or civilian clothes with green scarves); lass; flight; banner. Óðinn’s photo of the Peace Bridge is licensed by Creative Commons

nowadays: Peace Bridge between Fort Erie and Buffalo from Canadian side

![Group of veteran soldiers, National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, near Fort Monroe, Va., Capt. P.T. Woodfin, Governor (Philadelphia, Pa. : E.H. Hart, Copying, Landscape and Stereoscopic Photographer, 911 Arch Street, [between 1870 and 1880]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015649047/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/1s04503v-254x300.jpg)

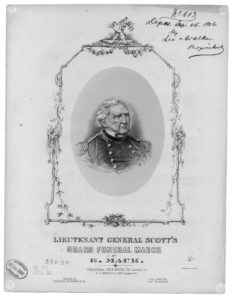

![Major Genl. Winfield Scott / Wood pinxt. ; Edwin sc. ([Philadelphia] : Publish'd by M. Thomas, 1814 Oct. 25.; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2012645312/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/3a26480r-194x300.jpg)