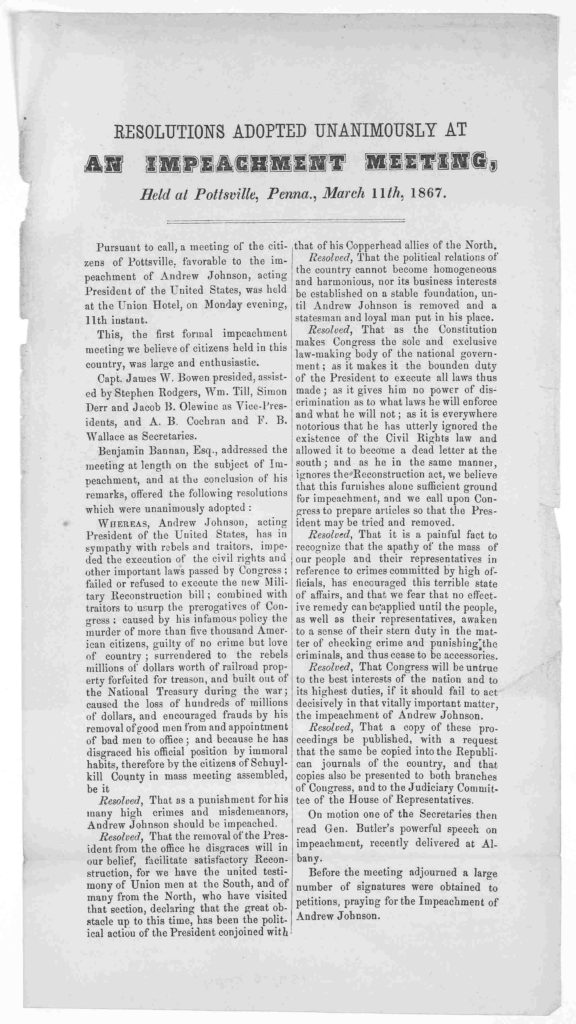

Are you kidding? I’m kind of sitting here dumbfounded, double-checking the calendar, but it doesn’t seem to be April 1st yet. I mean, we paid how many U.S. (1867) dollars for what? A whole bunch of remote ice, they say.

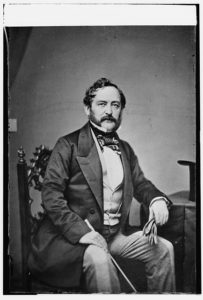

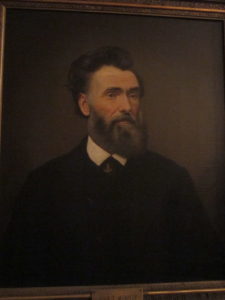

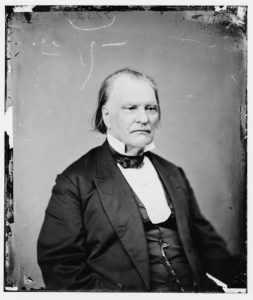

Over the decades I’ve been aware of Seward’s Folly. On March 30, 1867 Secretary of State William H. Seward and Russian ambassador Eduard de Stoeckl signed the treaty that sold Russian America (Alaska) to the United States for $7.2 million. Not all reaction was negative. An early editorial was mostly positive and praised the acquisition for it’s possibilities as the United States was in sort of commercial pivot to Asian markets. Strains of Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine might also have been it. Russian America boxed in part of British America.

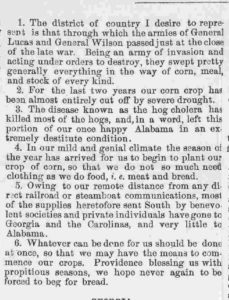

From The New-York Times March 31, 1867:

A Large Territorial Acquisition.

It is announced that, by treaty with Russia, our Government has acquired possession of the large Arctic domain known as Russian America.

There are from four to five hundred thousand square miles in this new Territory – fully enough to make nearly a dozen States as large as New-York. Be the bargain what it may, it is big enough.

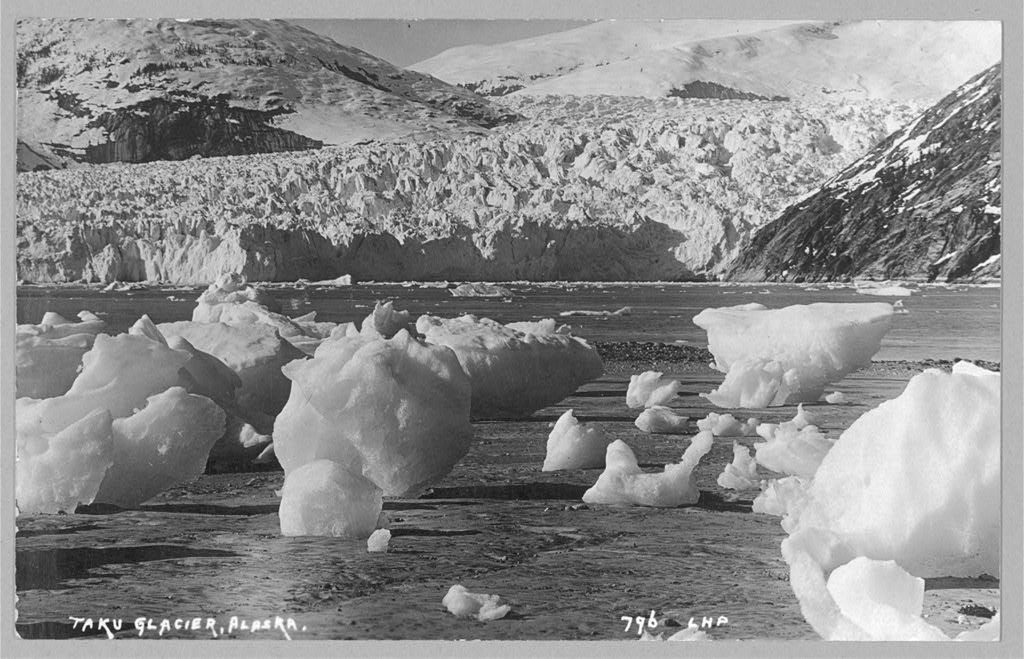

It’s value, however, is not likely to be measured by any theory of territorial expansion. The Russian ports on the coast, or rather in the islands bordering thereon, have had a small and diminishing fur trade for many years, and possibly this is susceptible of development under a new government and by means of American enterprise. But that at the best is a small matter. The great commercial advantages which would accrue to us from possessing a number of good harbors along a coast extending from latitude 55 to the Frozen Ocean hardly need to be pointed.

The Whale trade of the North Pacific would receive an impetus and encouragement it has never had before. Wherever our fast-growing commerce with Northeastern Asia extends the advantages of these Northern ports would be beneficially felt. The lines of commercial intercourse between our Western ports and China, Japan, &c., that we are now opening up, could hardly fail to profit by the additional feeders from a new quarter which this expansion of our political authority and commercial enterprise would necessarily supply. But the prime gain – if it is a gain at all for a leading Power to extend its sway beyond a certain limit – would have to be sought in the increased influence which our Government would acquire in all that affects individual States on this Continent, and the relations of the whole, alike with Asiatic and European powers. If it desirable to gain an influence thus paramount, there could be no more practical way of setting about it than by getting hold of a vast coast-line like this of Russian America, which incloses [sic] with an impassable wall a section of British territory running down from 50° to less than 55°, and gives us (beside the islands) an additional coast of over 1,000 miles on the Pacific. The advantages of this acquisition may not be without something of a counterbalancing kind. Increased power and dominion bring increased responsibilities. When we hear all about the terms of the treaty, and have weighed the question coolly and calmly, we shall no better how to value the purchase, and how to felicitate ourselves over having made it. Meanwhile we do not exactly see how it should have come to pass, as an evening paper has it, that in the precincts of the British Embassy at Washington the British lion should have been heard, yesterday, howling with anguish. Sir FREDERICK BRUCE is supposed to be a man of some common sense; and if all the preliminaries of the treaty spoken of are fair and square, no Government – least of all that of Great Britain – need feel greatly demoralized over the transaction.

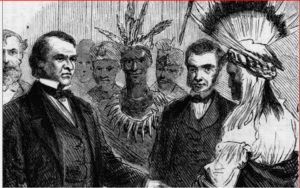

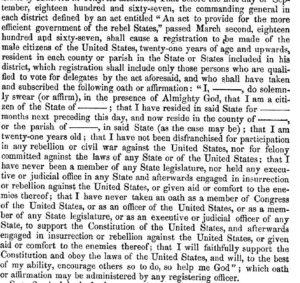

Harper’s Weekly did immediately pan the purchase. In it’s April 13, 1867 issue (page 226) saw a political motivation and said that size does not necessarily matter:

“King Andy and his man Billy lay in a great stock of Russian ice in order to cool down the Congressional majority”

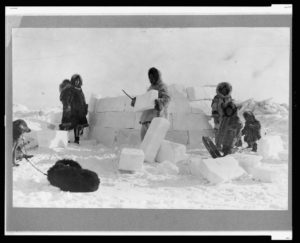

A more inopportune moment than this for the territorial expansion of the United States could not have been found; and it would hardly have been suggested except by an Administration conscious that it has forfeited the approval of the country and casting about to devise some appeal to that vulgar sense of national honor which mistakes size for splendor. The sale of Russian America to the United States for seven millions of dollars would be undoubtedly a good thing for Russia; but that it would be equally desirable for us is not evident. It is a territory covering some four hundred thousand square miles, and is inhabited by sixty or a hundred thousand people, half of whom are Esquimaux; and it would be practically a remote colony, with a foreign population. The advantages to us are the control of the fisheries and the fur trade; but the continuity of our coast line would be interrupted by that of the British possessions, a territory which Great Britain would not care to relinquish, but which would necessarily expose the friendly relations of this country and England to disturbance.

The paper went on to say that the United States should further assimilate its current territory and populations before continuing on its “‘manifest destiny” to rule the continent”.

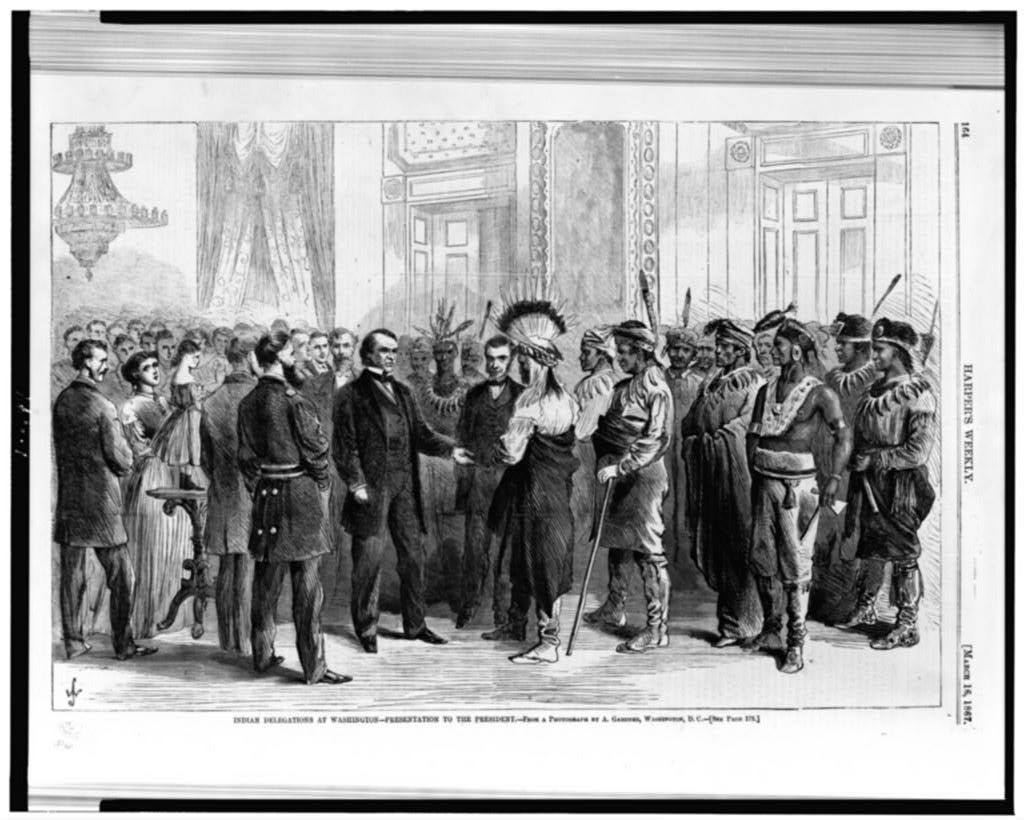

In an editorial in its April 27, 1867 issue entitled “THE NEW NATIONAL ICE-HOUSE” (page 248) Harper’s criticized the rapid and hush-hush way the treat was approved in the Senate without giving the people a chance to learn the details:

It would seem that the Secretary of State and the United States Senate might have consulted the people of the country in the usual way before enlarging the national domain by an arctic territory and the population by some scores of thousands of Esquimaux and nondescripts. It is surely a subject in which the people are all interested and upon which they have a right to be heard, and the manner in which this Russian treaty has been hurried through the Senate before there was fair opportunity for its intelligent discussion by the country is simply discreditable. The project was first revealed to the country on Sunday, March 31, and on Tuesday, April 9, the treaty was ratified. It can not be said to have been heartily approved any where except, as is reported, in California. …

It went on to say that the Louisiana purchase wasn’t like Alaska because the United States couldn’t let the mouth of the Mississippi be controlled by a foreign power; it thought that because of Secretary of State Seward’s ploy “the United States are about to enter upon a colonial system”. It worried about giving Russia over $7 million in gold when the country was heavily indebted, especially for an area which “under ordinary human conditions, will never be largely peopled except by savages”. The editorial thought that Mr. Seward was trying to refurbish his public image that was damaged when he “engineered” President Johnson’s disastrous 1866 “Swing Around the Circle”.

____________________________

Negotiations had been going on for awhile. Walter Stahr writes that Mr. Seward was at his D.C. home playing whist during the evening of March 29, 1867. About 10 P.M. Baron de Stoeckl came calling to announce that he had received “telegraphic permission” to sign the treaty and wanted to meet the next day to complete the work. The secretary of state didn’t want to wait: “Let us sign the treaty tonight.” The Russian was surprised because the state department was closed and both men’s aides were scattered around town. Seward told Stoeckl to show up at the state department before midnight and they could get to work. Mr. Seward got Senator Charles Sumner, the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, involved. Everyone got together at the State Department and hammered out a deal. The Americans refused Russian requests for changes, but sweetened the pot by about $200,000. The treaty was signed about 4 A.M. on the 30th.[1]

The House of Representatives approved the money for the acquisition in July, 1868, and the Russians finally got paid in August, 1868 (see check).

Even though Harper’s wasn’t a big fan of Andrew Johnson, it did stand up for him in the article before its April 13th Alaska editorial. It denounced General Benjamin F. Butler for insinuating that President Johnson was an accomplice in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Are “nondescripts” something like “deplorables”?

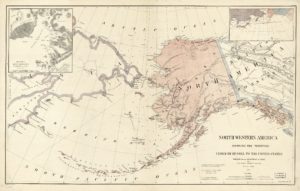

From the Library of Congress: Eduard de Stoeckl; 1867 map; cartoon originally published in the April 20, 1867 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper; igloo construction; Taku Glacier. From Wikipedia: Michael A. Haase’s photo of the Seward bust in Seward, Alaska.

- [1]Stahr, Walter Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. 2012. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2013. Print. pages 485-486.↩

![Maj. Genl. Philip H. Sheridan: U.S. Army (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, [between 1856 and 1907]; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/2002709994/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/3b50680r-212x300.jpg)

![Mardi Gras celebration in New Orleans, Tuesday, March 6 - Procession of the "Mistick Krewe of Comus" [Epicurean floats] ( Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, vol. 24, no. 601 (1867 Apr. 6), p. 41. )](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/3b10164u-1024x674.jpg)

![The new military commanders in the [in]surrectionary states ( Illus. in: Harper's weekly, v. 11, no. 536 (1867 April 6), pp. 216-217; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/00652830/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/3c27611v-300x242.jpg)

![Johnson's Georgetown and the city of Washington : the capital of the United States of America. (New York : A.J. Johnson, [1867] ; LOC: https://www.loc.gov/item/88693495/)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/dc1867-1024x805.jpg)