150 years ago Georgia conducted a five day election to determine if a state constitutional convention should be held, and, if so, who would be sent as delegates. Evidently many white conservatives didn’t vote. Here’s an early report from Savannah, which was the scene of a riot about a month earlier. From The New-York Times October 30, 1867:

… SAVANNAH, Tuesday, Oct. 29.

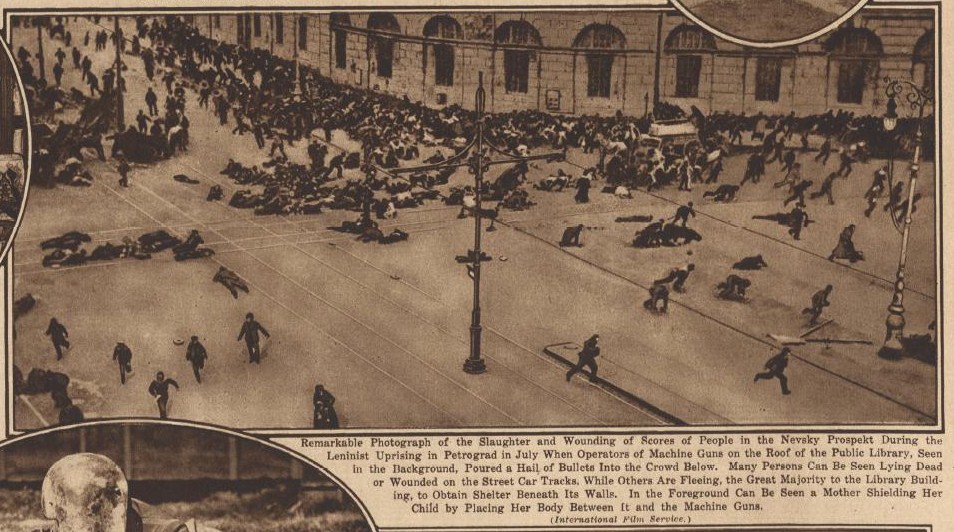

The election to-day passed off quietly. Many negroes from the country and some from South Carolina voted. The city vote was 602, and that of the county 440. About 250 votes were rejected, all of which, with the exception of three or four, were negroes. All the votes were for the Convention and the Radical ticket. Only one white vote was cast out of 174 city voters and 80 county voters. Many of the names given by the negroes could not be found upon the registry books. The Boston mulatto Bradley ticket is ahead.

Not a single arrest was made, and Savannah sustained its reputation as a peaceable city. The cooperation of the civil and military authorities was of the kindliest nature. …

And the military authority played an important part. In fact, General John Pope, commander of the Third Military District, added two days to the election period. From The New-York Times November 1, 1867:

… THE ELECTION IN GEORGIA.

With regard to the extension of time for the election in Georgia by Gen. POPE, it should be stated that there has been but one polling place in each county, except in the incorporated cities. As some of the counties are very large, and the voting by registration a novel and slow proceeding for the blacks, the additional time has been found necessary. …

The five-day tally showed that voters had approved the constitutional convention; overall conservative turnout was low. From The New-York Times November 4, 1867:

GEORGIA.

The Convention Election – Further Returns.

AUGUSTA, Ga., Sunday, Nov. 3.

From the election returns received at headquarters it is estimated that 105,000 votes were cast on the question of a Convention, out of 186,000 registered. The official count only can show the majority in favor of a Convention. Opposition candidates were nominated only in the northern part of the State, where the whites are largely in the majority. In the other portions of the State the Conservatives took no part in the contest, and the candidates favoring the Convention were elected by a large majority.

Here’s a summary from The Reconstruction of Georgia by Edwin C. Woolley (1901):

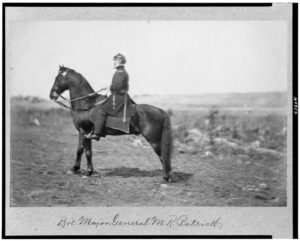

THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF POPE AND MEADE

In the Third Military District, of which Georgia was a part, the Reconstruction Acts were administered from April 1, 1867, to January 6, 1868, by General Pope, and from January 6 to July 30, 1868, by General Meade. The present chapter will describe, first, the manner in which these men conducted the political rebuilding of Georgia, and second, the manner in which they governed during this process.

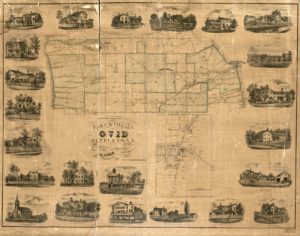

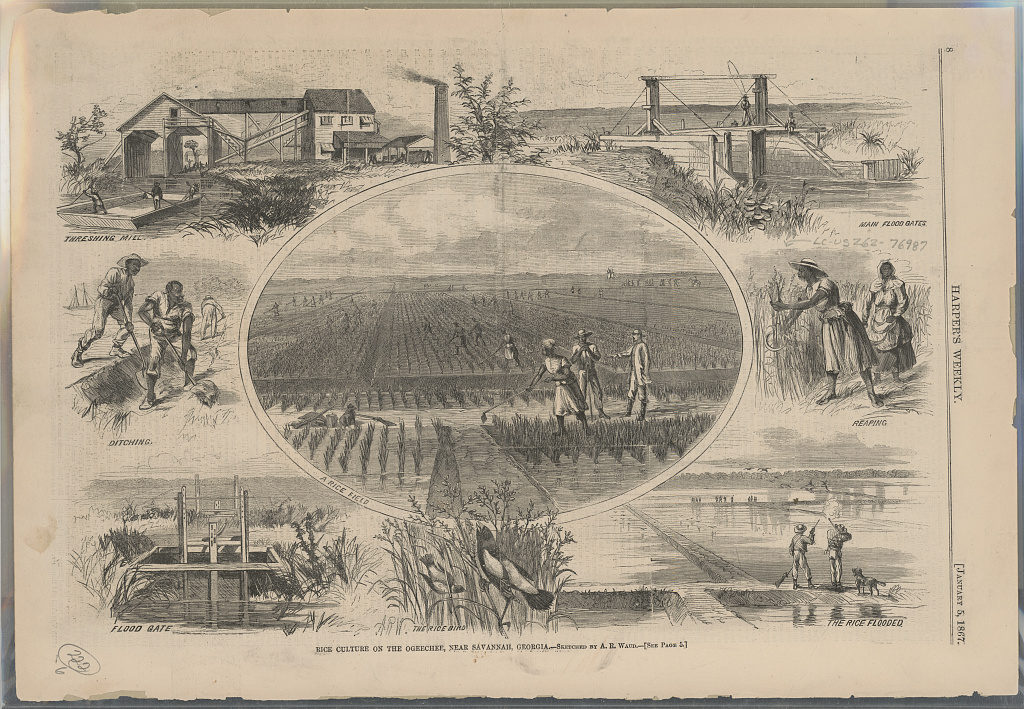

On April 8 Pope issued his first orders regarding the registration of voters. The three officers commanding respectively in the sub-districts of Georgia, Florida and Alabama were directed to divide the territory under them into registration districts, and for each of these to appoint a board of registry consisting as far as possible of civilians. On May 2 the scheme of districts for Georgia was published. The state was divided into forty-four districts of three counties each, and three districts of a city each. For each district the names of two white registrars were announced, and each of these pairs was ordered to complete the board by selecting a negro colleague. The compensation of registrars was to be from fifteen cents to forty cents for every name registered, varying according to the density or sparseness of the population. It was made the duty of registrars to explain to those unused to the enjoyment of suffrage the nature of this function. After the lists were complete they were to be published for ten days.

The unsettled condition of the negro population suggested to Pope the possibility that many negroes would lose their right to vote by change of residence. He therefore ordered on August 15 that persons removing from the district where they were registered should be furnished by the board of registry with a certificate of registration, which should entitle them to vote anywhere in the state.

The election for deciding whether a constitutional convention should be held, and for choosing delegates in case the affirmative vote prevailed, was ordered to begin on October 29 and to continue three days. Registrars were ordered to revise their lists during the fortnight preceding the election, to erase names wrongly registered, and to add the names of persons entitled to be registered. The boards of registry were to act as judges of election, but registrars who were candidates for election were forbidden to serve in the districts where they sought election.

The election was to occupy the last three days of October. On October 30 Pope extended the time to the night of November 2, in order to give the negroes ample opportunity to vote, which in their inexperience they might otherwise fail to do.

After the election the following figures were announced:

Number of registered voters in Georgia 188,647

Of these the negroes numbered 93,457

” the white men 95,214

Number of votes polled 106,410

” ” for a convention 102,283

” ” against a convention 4,127

The delegates elected were ordered to meet in convention on December 9th. …

In his book on Reconstruction Eric Foner reviews the southern state constitutional conventions as a group and writes that “Since most opponents of Reconstruction had abstained from voting, the total of just over 1,000 delegates included few Democrats or Conservatives, and a high rate of absenteeism further reduced their influence.” The delegates represented “the first large group of elected Southern Republicans”. Blacks made up about a quarter of delegates overall; carpetbaggers a sixth; most delegates were southern white scalawags.[1]

According to a 1947 thesis by Paul Laurence Sanford (pages 14-15), blacks made up 32 of 170 delegates to Georgia’s constitutional convention. A.A. Bradley was indeed one of the delegates. You can read more about Aaron Alpeoria Bradley in an article by Keri Leigh Merritt at the African American Intellectual History Society

- [1]Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerennial, 2014. Updated Edition. Print. pages 316-318.↩