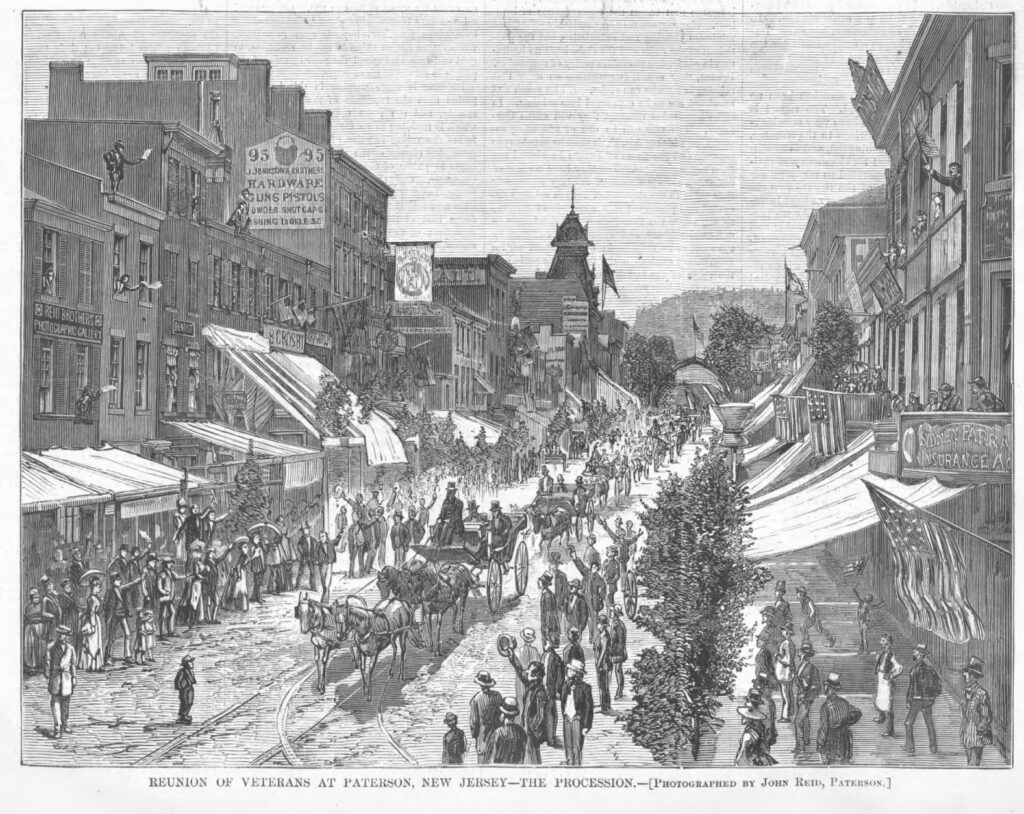

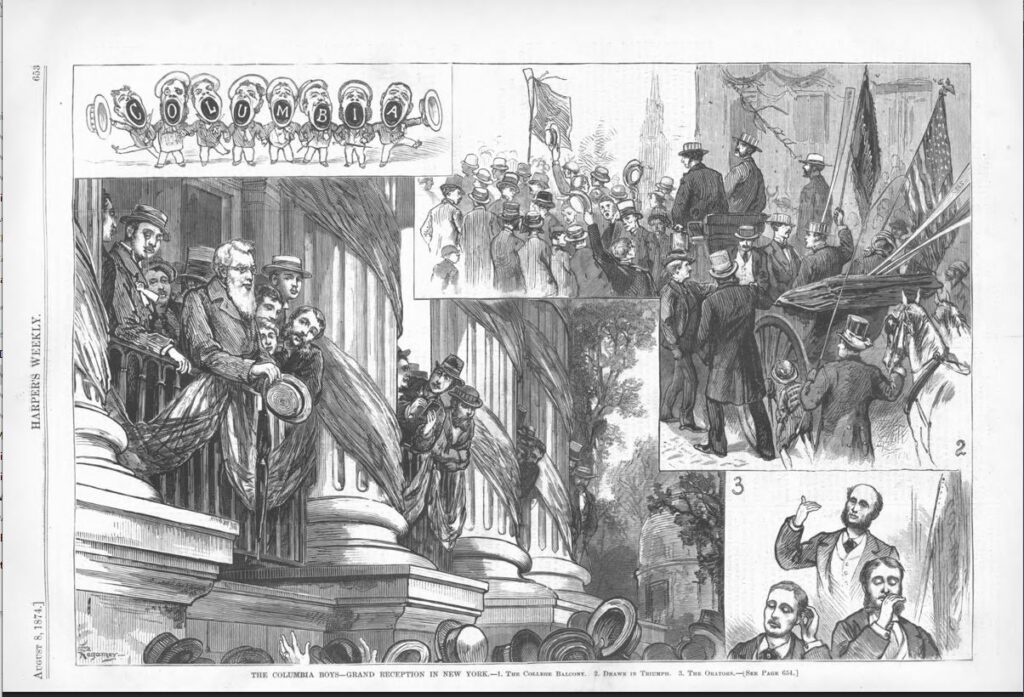

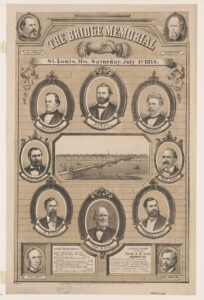

memorable bridge day

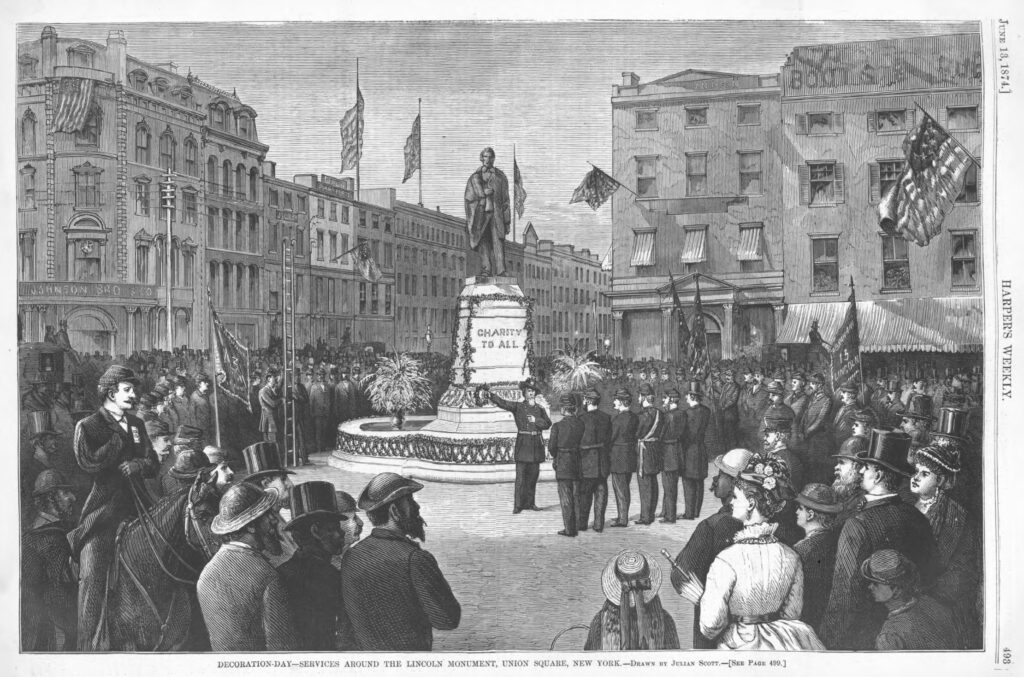

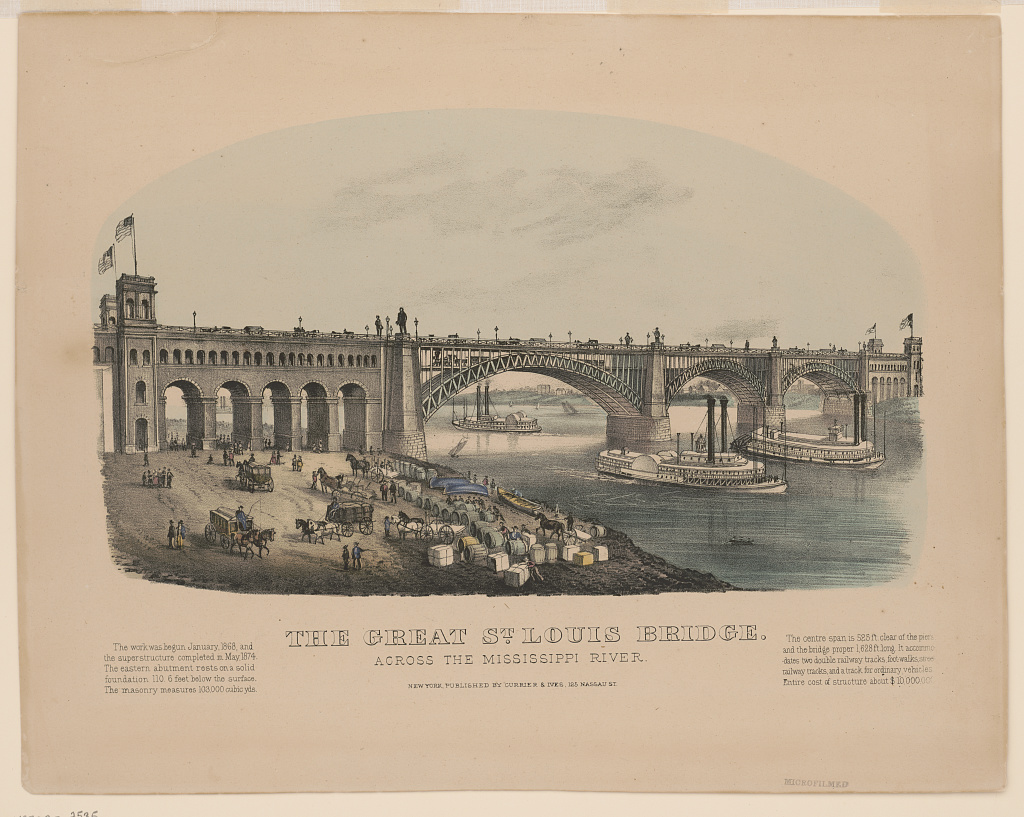

July 4, 1874 was a big day in the St. Louis area. People celebrated the official opening of a new bridge that connected Missouri and Illinois. The Eads Bridge was the first bridge to span the Mississippi River after its confluence with the Missouri River and “pioneered the large-scale use of steel as a structural material, leading the shift from wrought-iron as the default material for large structures.” During the the huge gala on the Fourth, the bridge’s designer and builder, James Buchanan Eads, was one of the passengers on a train that crossed the bridge from the Illinois side. On the Missouri side a procession of 100,000 people met the train. There was a magnificent fireworks display in the evening. Here’s the beginning of a very long article about the bridge and the celebration from the July 5, 1874 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune:

ST. LOUIS BRIDGE.

Formal Inauguration of the Great

Structure Yesterday.

The Bridge a Marvel of Modern

Engineering.

A Hundred Thousand People In the

Grand Procession.

The Great Bridge Illuminated with

Fireworks at Night.

The River Crowded with Steamer-Loads

of Spectators.

History of the Enterprise—Do-

Description of the Work.

THE INAUGURATION.

Special Dispatch to The Chicago Tribune.

St. Louis, July 4.— Throughout a hundred years of lazy indifference and substantial prosperity, St. Louis has known no such gala day as this has been. Never before was there such universal enthusiasm and such a spontaneous outpouring of the people to do honor to any passing event, or to publicly rejoice over real or imaginary glory. Although the confidence of the St. Louis people in the ultimate success of the bridge enterprise has remained unshaken ever since the work was inaugurated, still no great public enthusiasm manifested itself until the completion of the first arch, since which time no topic of conversation has been so general as that of the bridge project, and as the work continued steadily to go on, and the huge superstructure gradually assumed a symmetrical form, and began to exhibit indications of tho ultimate grandeur of this groat triumph of modern engineering skill, local pride was increased proportionately, and kept on growing.

work in progress

THE CULMINATION

occurred today. For weeks past preparations have been making on a most elaborate scale for a formal opening of the bridge, and an appropriate celebration on the great national holiday. The peculiar adaptability of the bridge for the exhibition of the fireworks seems naturally to have suggested the advisability of an entertainment of this character, and arrangements were accordingly effected some weeks ago for a grand scenic display of pyrotechnics on the evening of the 4th. Soon after the adoption of this enterprise, was conceived the idea of a

A GREAT PROCESSION,

comprised of representatives of each and all of the diversified industrial interests of tho city, together with a full turn out of the various military organizations, societies, clubs, and the fire department; in a word, to have represented everything calculated to make the pageant more imposing or to do honor to the occasion. This suggestion was seized on with avidity by the public, and the various members of the Merchants’ Exchange, as also numerous private citizens of energy and liberality, which have for some days been industriously engaged in perfecting a plan of organization for the procession and the general details of the celebration. But not in St. Louis alone was this great interest felt in the bridge. For several days past the railroads and steamers have been bringing crowds of our country cousins and friends from other cities. It is thought that

FULLY 30,000 STRANGERS

are in the city to-night.

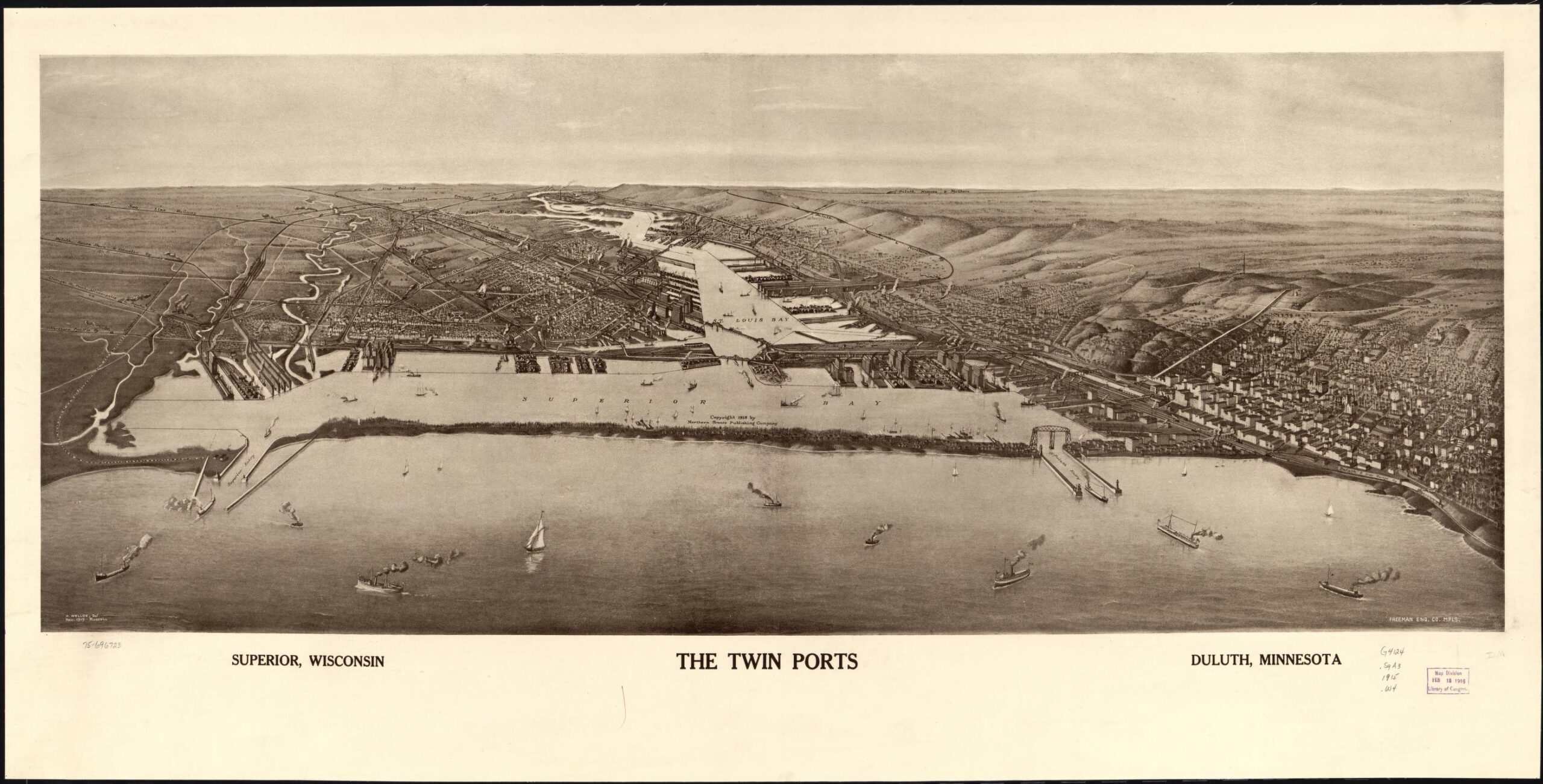

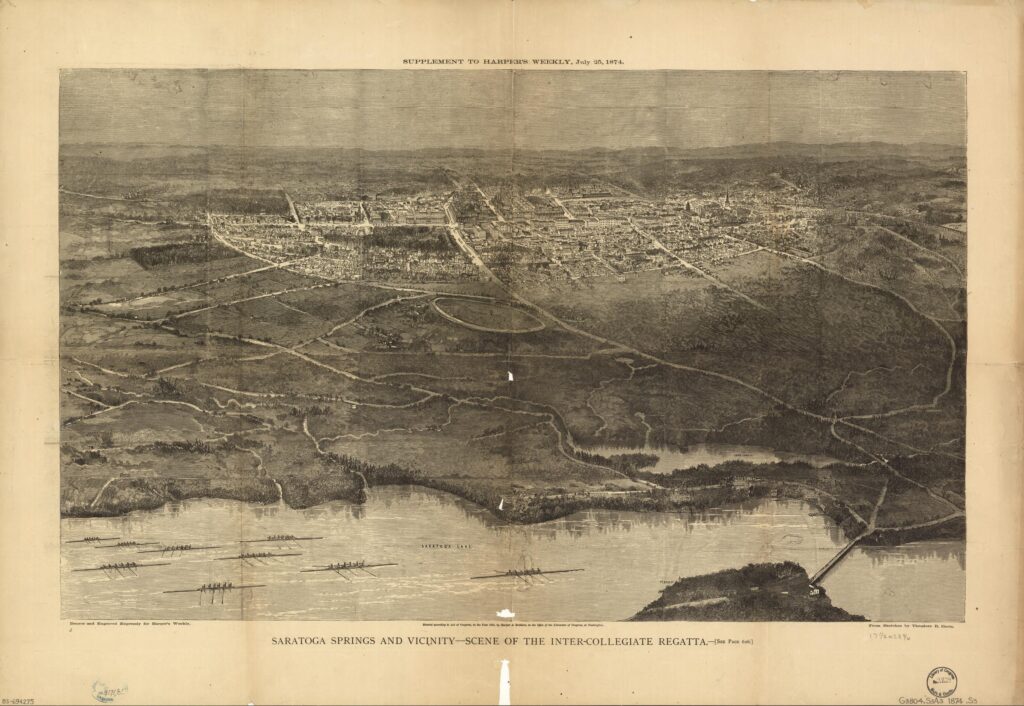

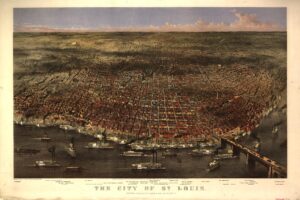

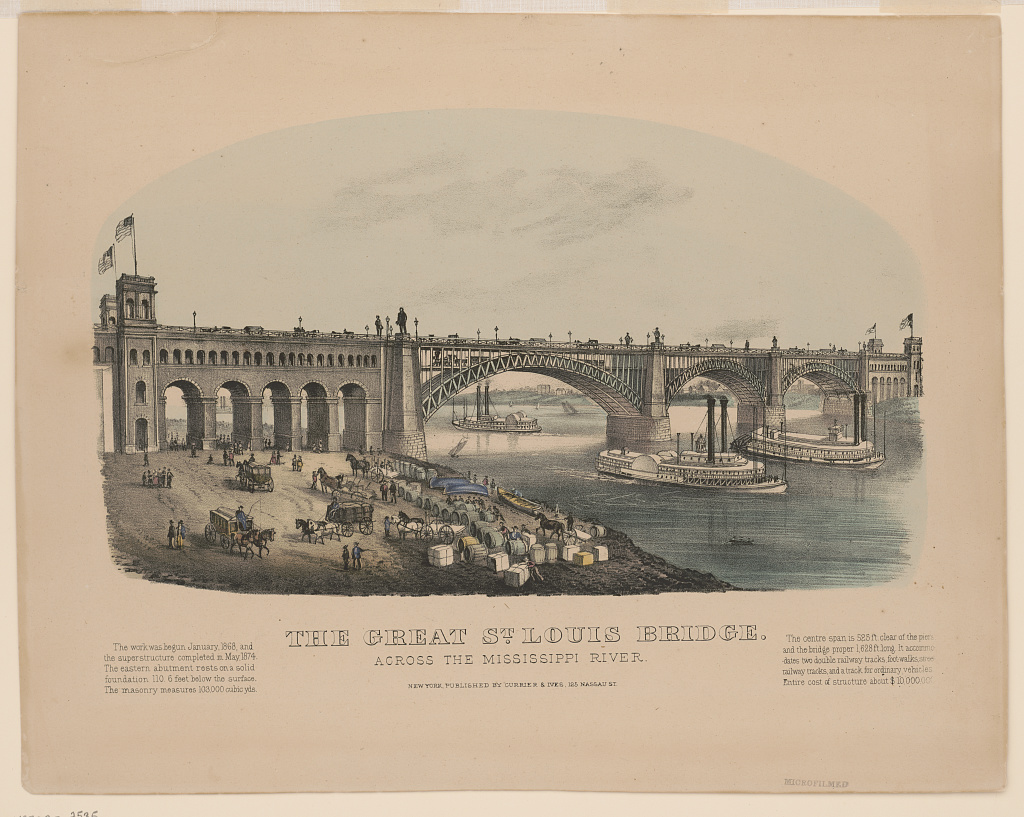

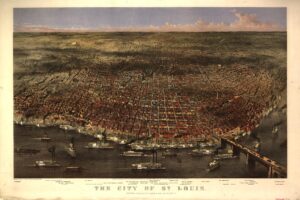

bird’s eye view of new bridge

The sun rose this morning to shed its light upon a perfect sea of bunting. Fourth street, Fifth street, and Washington avenue, and the principal thoroughfares, presented a truly magnificent scene, being hung with garlands, flags, mottoes, and inscriptions arranged in most attractive shape. The crowd began to assemble upon the streets at a very early hour, and at 9 o’clock it is no exaggeration to state that

THREE HUNDRED THOUSAND PEOPLE

were rushing and surging up and down the streets, pushing their way into the track of the procession, and being driven back by the police, only with truly American perversity to seek another locality and being driven back by the police, only with the American perversity to seek another locality in which to elude the vigilance of the officers and get under the hoofs of the horses or the wheels of the carts.

Tho procession formed on Washington avenue, and at 0 o’clock moved toward the bridge, led by the Marshals and a United States military company. Nearly every branch of industry, every commercial interest, seemed to have an appropriate representation. It were idle to attempt enumeration. Also all the leading societies,

clubs, and local organizations were represented.

MOTTOES, BANNERS, AND DECORATIONS INNUMERABLE

were displayed to an excited and enthusiastic throng who, from the streets, the windows, and the [t]ops of tho loftiest houses, cheered the pageant as it steadily illed [filed?]past. At the west approach of the bridge the head of the column stopped. In the meantime

A TRAIN OF FIFTEEN PULLMAN CARS,

drawn by three engines, had crossed from the east side, bringing a number of distinguished persons, [including many politicians, Capt. J. B. Eads (“architect of the bridge”), and Gen. W. S. Hancock]. Upon the meeting of the train and procession, Mr. G.B. Allen, President of the Bridge Company, introduced Mrs. Julius S. Walsh, who

CHRISTENED THE BRIDGE,

making the following remarks:

With the waters of the Atlantic, tho Pacific, the Gulf, and the Lakes commingled, emblematic of the union effected by the might spans, I christen this structure the Illinois & St. Louis Bridge, and invoke the blessings of the Almighty on it, its builders, and the commerce to which it is henceforth and forever dedicated.

After which she

SPRINKLED THE STRUCTURE

from six silver pitchers containing the various waters referred to. Water from the Northern Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans had been forwarded from Boston, San Francisco, Chicago, and New Orleans by the respective Postmasters of those cities.

After the christening came the speeches. After the addresses of welcome by Mayor Brown, Messrs. Beveridge, Woodson, Hendricks, Senator Ferry, of Michiganand others, offered appropriate remarks. Tho procession then moved on, occupying some four hours in passing, and extending in length from 12 to 14 miles.

THE FIREWORKS.

In the evening, soon after dark, the display of fireworks from the bridge began. Tho roofs of all the high buildings within three or four squares of the river were covered with people, seats having been arranged for their convenience. The levee, wharfboats, lighters, and barges were thronged with humanity, while a fleet of thirty-one river steamers and innumerable smaller boats, extending about a third of a mile below, afforded an opportunity to thousands to view the exhibition without interruption. There is no doubt that this display of pyrotechnics is the grandest thing of this kind that has been witnessed in America, and but very rarely have attempts been made in Europe to produce so grand a sight. This evening the whole heavens were at one instant aglow with a ruddy light, the next as bright as day with the most brilliant flashes, when a heavy black cloud of smoke from the fleet below, wafted by a gentle breeze from the south, cast a gloomy shadow over the whole until it passed away, and the air was again filled with thousands of particles of fire, as varied in color as the rainbow, and seemingly not less beautiful. Shortly after 9 o’clock the display from the bridge ceased, the fleet returned to the wharves, and the throng dispersed. …

spanning the Mississippi

Bridge designer and builder James B. Eads grew up in St.Louis. According to William M. Fowler, Jr., James Eads was “an expert salvager:

During the 1840s river navigation was a hazardous business and wrecks were common. The young Eads, alert to opportunities, had started a salvage business. Although he had no formal training in engineering or design, he invented and patented a diving bell and a floating pump device. These ingenious new machines allowed him to lift apparently unsalvageable wrecks. By the mid 1840s James Eads was one of the best known and wealthiest rivermen along the entire Mississippi.

Mr. Eads also contributed to the Union Civil War effort. As James M. McPherson wrote,

Eads contracted in August 1861 to construct seven shallow-draft gunboats for river work. When completed before the end of the year, these craft looked like no other vessel in existence. They were flat-bottomed, wide-beamed, and paddle-wheeled, with their machinery and crew quarters protected by a sloping casemate sheathed in iron armor up to 2.5 inches thick. Because this casemate, designed by naval constructor Samuel Pook, reminded observers of a turtle shell, the boats were nicknamed “Pook’s turtles.” Although strange in appearance, these formidable craft each carried thirteen guns and were more than a match for the few converted steamboats the South could bring against them.

four Pook’s turtles under construction by Eads’ company

working on deck of one of the four

finished product: USS Carondelet

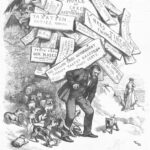

It was a different story on Independence Day 1874 for a bridge in Lewiston, Pennsylvania. According to documentation at the Library of Congress, the bridge was destroyed by a tornado on that day.

Missouri and Mississippi rivers join

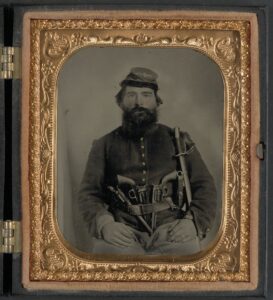

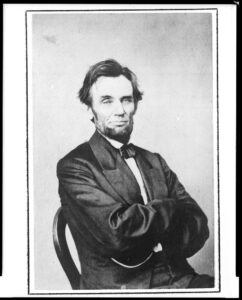

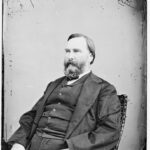

James Buchanan Eads

PA bridge collapsed on the Fourth

James Buchanan Eads is a member of the National Inventors Hall of Fame. You can read a good post about James B. Eads at The Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial. A bio at PBS’s American Experience notes that “In July 1884, Britain’s Royal Society of the Arts awarded Eads the Albert Medal for ‘services he had rendered to the art of engineering.’ He was the first American to receive the honor.” The Wikipedia link in first paragraph explains that James Buchanan Eads was “named for his mother’s cousin, future President of the United States James Buchanan.” According to HistoricBridges.org, the Eads Bridge is a National Historic Landmark. HistoricBridges provides much information about the bridge, including a link to a site with even more information – Eads Bridge by David Aynardi. The bridge was damaged twice by tornadoes. See a picture of the 1896 damage here

Citations for paragraphs by Fowler and McPherson: [Fowler Jr., William M. Under Two Flags: The American Navy in the Civil War. Bluejacket Books, 2001. Print. page 130.] [McPherson, James M. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989. Print. page 393.]

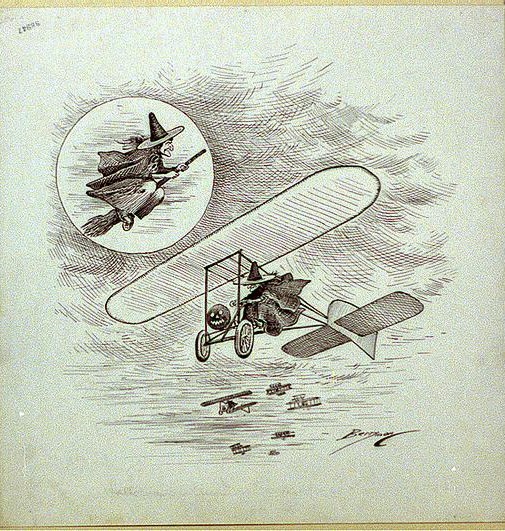

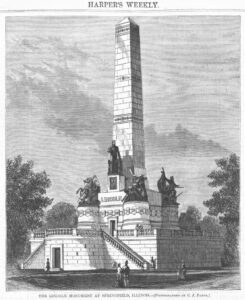

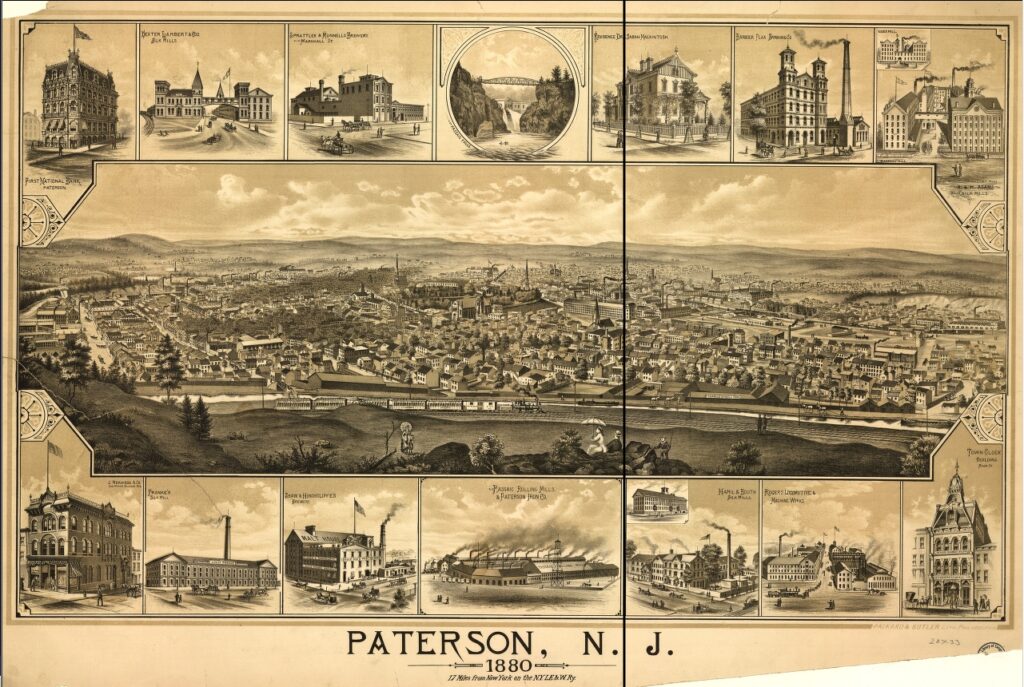

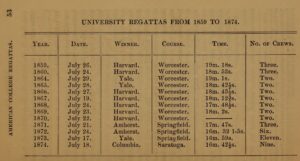

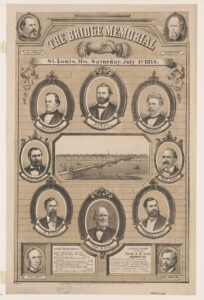

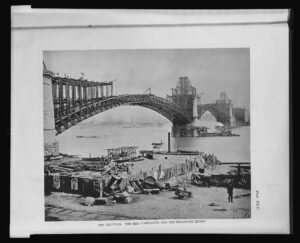

From the Library of Congress: bridge memorial – I don’t see any evidence that President Grant was on hand for the festivities; the July 5, 1874 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune – the bridge article is on pages 1 and 12; ribs completed; the bird’s-eye view; the completed bridge at St. Louis; upper-left section of Lloyd’s 1863 map of the Mississippi from St. Louis to the Gulf – the confluence with the Missouri is a few miles upstream from St. Louis; the portrait of James B. Eads; the collapsed bridge in Lewiston, Pennsylvania;; the great St. Louis bridge

From Naval Heritage and History Command: four boats under construction in St. Louis; working on the deck of one of the armored gunboats; USS Carondelet

still standing today