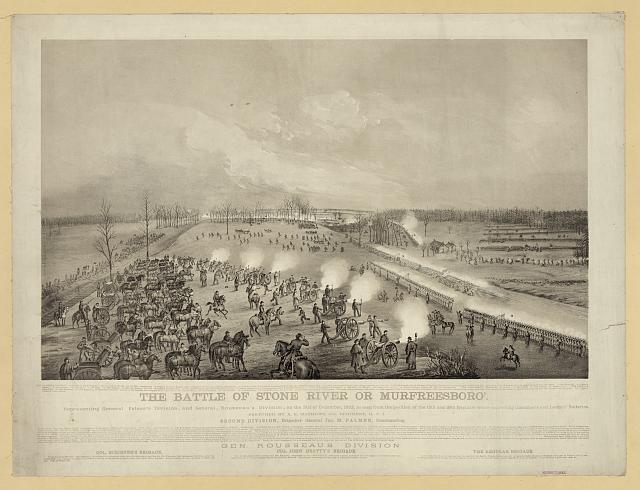

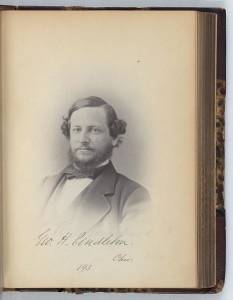

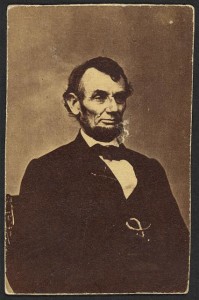

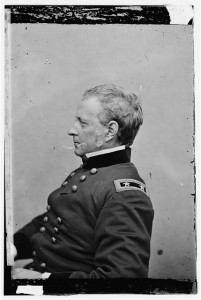

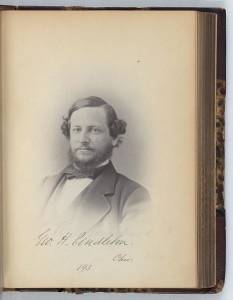

‘Gentleman George’ Pendleton harangues against despotic Government

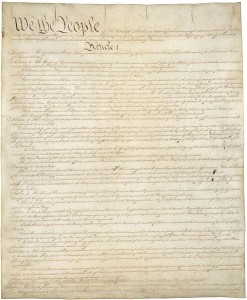

This attack on traitorous Copperheads has a good summary of the Constitutional justification for the three laws passed by the 37th Congress that gave a great deal of power to the Executive branch.

From The New-York Times March 11, 1863:

The Copperheaded Complaint of “Tyranny.”

VALLANDIGHAM told the New-York Copperheads, in his recent speech, that “nothing was wanting to make this Government a complete and absolute despotism, as iron and inexorable in its character as the worst despotisms of the Old World, or the worst of modern times, even to BOMBA of Naples.” His colleague, PENDLETON, in his harangue before the same set of rebel sympathizers, on Monday evening, substantially reiterated the assertion.

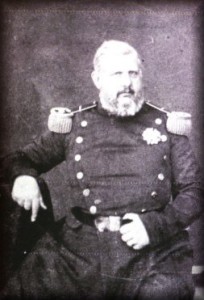

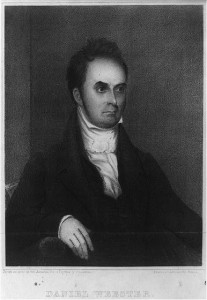

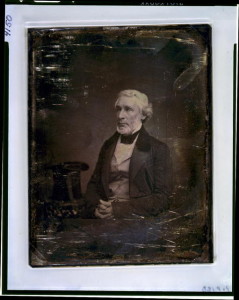

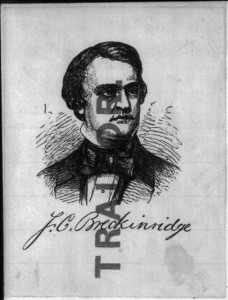

King Bomb – Vallandigham compared him to Lincoln administration

Of course — of course. This precious pair have got the cue precisely. They are well up to the true method of Sedition made Easy. The first business always is to affect a dreadful concern for the liberties of the country. CATALINE understood it; and so did his secret friends CLODIUS and CAESAR. It shocked them all beyond measure that the Senate should cloth CICERO with extraordinary powers; in the name of Freedom and the Constitution, they denounced it, even though at that very time the plot had been laid to kill the Senators and burn the city. The Tories of our Revolution understood it. They poured out their objurgations upon the Continental Congress for voting extraordinary powers to WASHINGTON in the crisis of the struggle, and did it in no other name than that of outraged and down-trodden Liberty. Our people, within their own memory, saw this same thing in the Jacobinical rebellion against the last French Republic. The club-leaders had covered half of Paris with their barricades; blood had already begun to flow; it was announced to the National Assembly that “in an hour, perhaps, the Hotel de Ville will be taken.” And yet even in that terrible juncture, when anarchy and ravage were at the very doors, the proposition to confer full powers upon Gen. CAVAIGNAC and to declare Paris in a state of siege, was inveighed against by the Reds as endangering the public liberty! It is so everywhere and always. Extraordinary powers, in terrible emergencies, have saved free States again and again; but never without an outcry from public enemies against the tyranny of it, and an effort to make it tell in their own favor. The very men, on such occasions, who are either actively engaged in or in secret sympathy with the attempts to destroy the public liberties, are invariably the very men who are the loudest in their maledictions upon extraordinary powers, and in their apostrophes to Constitutional Liberty.

“blackest treason was brooding on his heart”

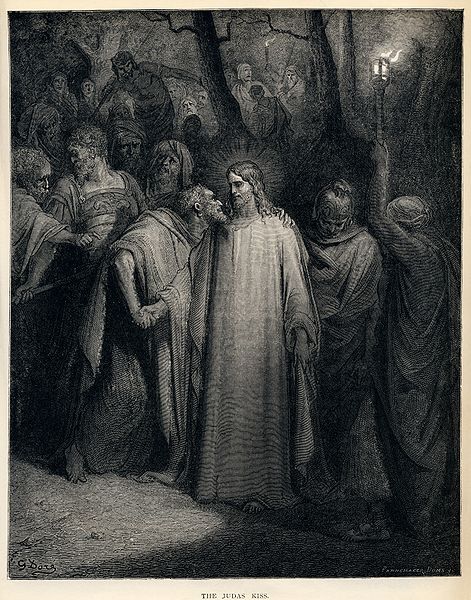

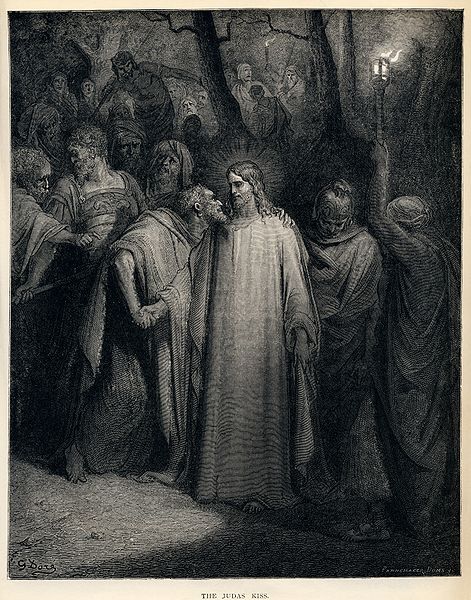

What does this man VALLANDIGHAM care about constitutional liberty? He cares precisely the same as his friend JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE did, when, on the 16th day of July, 1861 — three months after the taking of Sumter by the rebels — he stood up in his seat in the Senate and declaimed by the hour against the resolutions approving of the acts of the President in calling out the troops and declaring the blockade. “We are rushing,” said BRECKINRIDGE, “and with rapid strides, from a constitutional Government into a military despotism. The civil authorities are paralyzed, and practical martial law is being established all over the land. The like never happened in this country before, and it would not be tolerated in any country in Europe which pretends to the elements of civilization and liberty.” This is VALLANDIGHAM’s sentiment exactly. The same BRECKINRIDGE, who was filled with such virtuous indignation over the outraged Constitution, was soon at the head of a rebel brigade, under the flag of JEFF. DAVIS, battling for the destruction of the Republic. At the very time he was ranting about the sacred guarantees of the Constitution, he was meditating how best to shipwreck that Constitution. The blackest treason was brooding on his heart. That, and that only, was his inspiration. VALLANDIGHAM’s prompting is identical with it. He mouthed indignation before the Club with just the same sincerity that BRECKINRIDGE did before the Senate. They are precisely the same champions of the Constitution as Judas, who bore the bag, was a champion of the poor — precisely the same disciples of the Constitution as Judas was a disciple of the Master, whom he betrayed with a kiss.

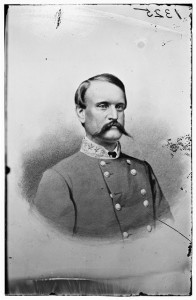

General Breckinridge has gone to his own place

Judas, we are told, went to his own place. BRECKINRIDGE has gone to his. Let VALLANDIGHAM go to his, and his whole reprobate pack after him. They belong to the Confederacy. Their souls are there; so should be their bodies. Double-dyed traitors like them, they have no business on loyal ground. The Constitution wants none of their vindication. It gives the lie to the grievances trumped up in its behalf. The extraordinary powers conferred upon the Government, instead of being an encroachment upon it, were expressly authorized by it. It has invested Congress with an unrestricted power “to raise armies,” and “to provide for the calling forth of the militia to execute the laws of the Union, and suppress insurrections.” Congress has done this in the Conscription bill. It has authorized Congress “to coin money and regulate the value thereof.” Congress has done this in the Currency bill. It has authorized the suspension of habeas corpus, “when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it.” Doubts have existed whether the President constitutionally has this power without the vote of the legislative branch; but this has ceased to be a practical question, since Congress, by formal regular vote, has sanctioned the President’s exercise of the power. No unconstitutional powers of any sort have been granted. Every means which have been ac[c]orded to the President, to enable him to fulfill his oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution,” have been taken strictly from the domain of the Constitution. The Constitution has not been violated nor dishonored, except by rebels and their symphathizers. If its practical working has been in any respect changed, it has been for its own preservation, and in accordance with its own provisions for just such emergencies. No man has experienced oppression from this. Even in the cases of the so-called “arbitrary arrests,” about which there has been so much clamor, the way was always open, except where overt treason had been committed, to recover on the spot every civil privilege. It was simply necessary to take the oath of allegiance, which no really loyal man ever accounts a hardship. However bad their conduct, if it did not amount to absolute treason, this was sufficient. They who refused thus to purge and pledge themselves, though they aspired to be martyrs, had not the slightest reason for complaint. It is an insufferable outrage upon the intelligence and the loyalty of this community for a man to stand up here and pronounce the present Administration of our Government to be worse than the tyranny of BOMBA. The very fact that the Government can with impunity be so traduced stamps its author as a miscreant.

Like President Lincoln, Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies (lived 1810-1859) was apparently prepared to do whatever it took to keep his country united. However, from the perspective of 150 years, it seems the Times was justified in its condemnation of Vallandigham’s comparison. After the North beat the South, Lincoln wanted to hear the sweet strains of Dixie; when the island of Sicily declared its independence in 1848:

the King assembled an army of 20,000 under the command of General Carlo Filangieri and dispatched it to Sicily to subdue the Liberals and restore his authority. A naval flotilla sent to Sicilian waters shelled the city of Messina with “savage barbarity” for eight hours after its defenders had already surrendered, killing many civilians and earning the King the nickname “Re` Bomba” (“King Bomb”).

I don’t know if the king was actually with the flotilla when it bombed Messina.

An early Made Easy book was 1910’s Calculus Made Easy. It is still available.

wrote the book for traitors