Louisiana’s political affairs were still unsettled in the aftermath of the September 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, in which the white supremacist White League began an insurrection to take control of the state government. At that time federal troops put the insurrection down. In December 1874 President Grant sent General Philip Sheridan to Louisiana to investigate the situation and possibly take command of the Department of the Gulf. Sheridan made it to New Orleans a few days before the organization of the state legislature on January 4, 1875. On that day, even though they were outnumbered 52-50, Democrats attempted to take control of the assembly by installing five Democrats who had not been declared elected by the “Returning Board”. Affairs were confusing and chaotic. United States General Régis de Trobriand and a few soldiers arrived in the hall and eventually removed the five non-elected Democrats. The Democratic members then marched out of the assembly. General Sheridan assumed command of the Department of the Gulf on the night of January 4th after the events in the legislature. The next day he contacted Secretary of War William W. Belknap to suggest that the federal government declare White League ringleaders to be “banditti,” so they could be tried by military commission.

_____________________________

The federal troop intervention in the state legislature and Sheridan’s banditti comments caused a major brouhaha throughout the country – north and south. Eric Foner has written that the public supported federal troops putting down the Liberty Place insurrection but opposed the military’s intervention in the state legislature on January 4th, which showed “the dangers posed by excessive federal interference in local affairs.” United States troops taking charge in the state assembly caused “more Northern opposition than any previous federal action in the South.” Citizens in Boston met “at Faneuil Hall to demand Sheridan’s removal” and praised the White League as “defenders of republican freedom.” Wendell Phillips was at that meeting. When he said President Grant should have the power to protect the interests of the freed slaves, the crowd hissed, laughed, and told him to sit down. Louisiana affairs “divided and embarrassed the Grant Administration.” Things settled down after a Congressional committee headed by William A. Wheeler from New York came up with a compromise in February – Republicans would control the Louisiana Senate, Democrats would get control of the lower house, and Republican Governor Kellogg, considered a usurper by the Democrats, would remain in office. The Louisiana problems led the Republican party to become more hands-off in the South.[1]

Here are a few clippings from reaction around the country. According to a page 1 headline in January 5, 1875 issue of The Memphis Daily Appeal, the January 4th incident was “the last straw.” The accompanying article detailed the events in the legislature. In it’s January 13, 1875 issue Richmond’s Daily Dispatch said more Republicans would oppose the Grant Administration’s handling of Louisiana if they weren’t afraid of strengthening the Democratic party. The paper was glad Sheridan had to explain his “banditti” comments and stated that “The White League is mainly composed of gentlemen superior in every civil virtue to Sheridan himself.”

Harper’s Weekly provided a lot of coverage and had much to say about the events in Louisiana. Louisiana Governor Kellogg did not have the constitutional right to use federal troops without the permission of the U.S. president and the governor could make the request only when the state legislature was not in session. The paper opposed any desperate policy ventures to reunite the Republican party or restore its prestige. A couple cartoons summarized President Grant’s January 13th message to Congress. (According to the front-page article in The Memphis Daily Appeal on January 5th, General De Trobriand first appeared in the hall by himself after Democrat L.A. Wiltz took over the speakership and the five extra Democrats were seated. During the swearing in ceremony the sergeants at arms tried to prevent Republicans from leaving the hall. “Several scuffles ensued, when, on motion of Mr. George DuPre, General De Trobriand was sent for, who cleared the lobby of the police and spectators at the speaker’s request.” About 15 minutes later the general returned with troops and two letters from Governor Kellogg requesting the troops to remove the members not validated by the Returning Board. After the removal L.A. Wiltz eloquently protested the federal interference.) Another cartoon printed a letter to the editors of the New York Tribune that seemed to support assassinating President Grant. Also, some Democrats and members of the White League were pushing back.

Sheridan didn’t turn out to be a banditti buster. According to Eric Foner, in the same section of his book cited above, Grant sent Sheridan to Louisiana to “protect the colored voter in his rights,” and ordered Sheridan to use federal troops to keep Governor Kellogg in office and squelch the violence. Too much of the country didn’t like the events of January 4th and Sheridan’s baditti letter. General Sheridan got married on June 3, 1875. He and his wife moved to Washington, D.C.

You can read more about Sheridan’s famous Ride during the Civil War at the National Park Service. French-born Régis de Trobriand was naturalized in 1861 and served in the Union army throughout the war. His brigade performed courageously at the Wheatfield during the Battle of Gettysburg. He fought in the Indian Wars, and in 1874 President Grant assigned him to New Orleans.

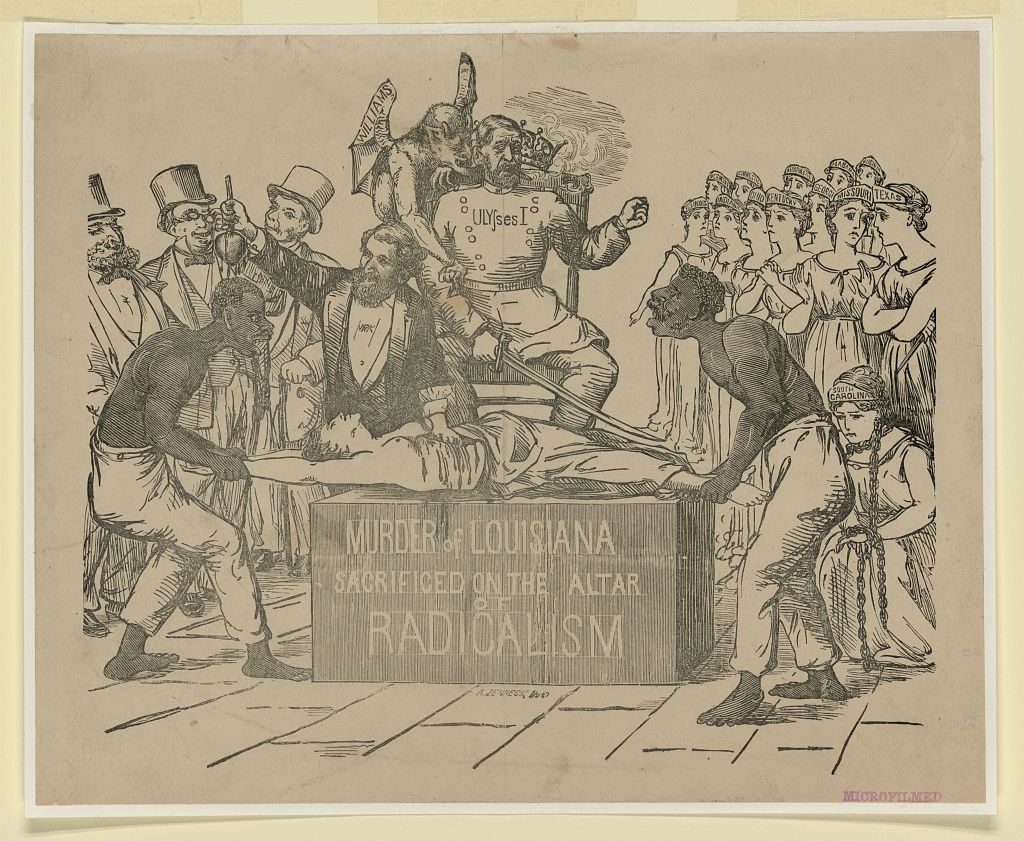

From the Library of Congress: the December 29, 1874 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune; Régis de Trobriand; the Murder of Louisiana: “President Ulysses S. Grant and Congress turned a blind eye to the disputed 1872 election of carpetbagger William P. Kellogg as governor of Louisiana. In this scene Kellogg holds up the heart which he has just extracted from the body of the female figure of Louisiana, who is held stretched across an altar by two freedmen. Enthroned behind the altar sits Grant, holding a sword. His attorney general, George H. Williams, the winged demon perched behind him, directs his hand. At left three other leering officials watch the operation, while at right women representing various states look on in obvious distress. South Carolina, kneeling closest to the altar, is in chains.”

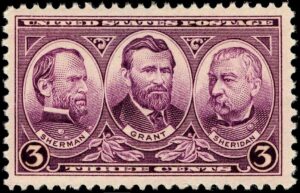

I got the stamp at the Wikipedia article about Philip Sheridan. That’s the reference for his marriage, along with the Harper’s Weekly cartoon. Most of Harper’s Weekly for 1874 is at HathiTrust.

Sheridan didn’t turn out to be a banditti buster. According to Eric Foner, in the same section of his book cited above, Grant sent Sheridan to Louisiana to “protect the colored voter in his rights,” and ordered Sheridan to use federal troops to keep Governor Kellogg in office and squelch the violence. Too much of the country didn’t like the events of January 4th and Sheridan’s baditti letter. General Sheridan got married on June 3, 1875. He and his wife moved to Washington, D.C.

You can read more about Sheridan’s famous Ride during the Civil War at the National Park Service. French-born Régis de Trobriand was naturalized in 1861 and served in the Union army throughout the war. His brigade performed courageously at the Wheatfield during the Battle of Gettysburg. He fought in the Indian Wars, and in 1874 President Grant assigned him to New Orleans.

From the Library of Congress: the December 29, 1874 issue of The Chicago Daily Tribune; Régis de Trobriand; the Murder of Louisiana: “President Ulysses S. Grant and Congress turned a blind eye to the disputed 1872 election of carpetbagger William P. Kellogg as governor of Louisiana. In this scene Kellogg holds up the heart which he has just extracted from the body of the female figure of Louisiana, who is held stretched across an altar by two freedmen. Enthroned behind the altar sits Grant, holding a sword. His attorney general, George H. Williams, the winged demon perched behind him, directs his hand. At left three other leering officials watch the operation, while at right women representing various states look on in obvious distress. South Carolina, kneeling closest to the altar, is in chains.”

I got the stamp at the Wikipedia article about Philip Sheridan. That’s the reference for his marriage, along with the Harper’s Weekly cartoon. Most of Harper’s Weekly for 1874 is at HathiTrust.

_____________________

- [1]Foner Eric, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerenial ModernClassics, 2014. Page 554-555. ↩