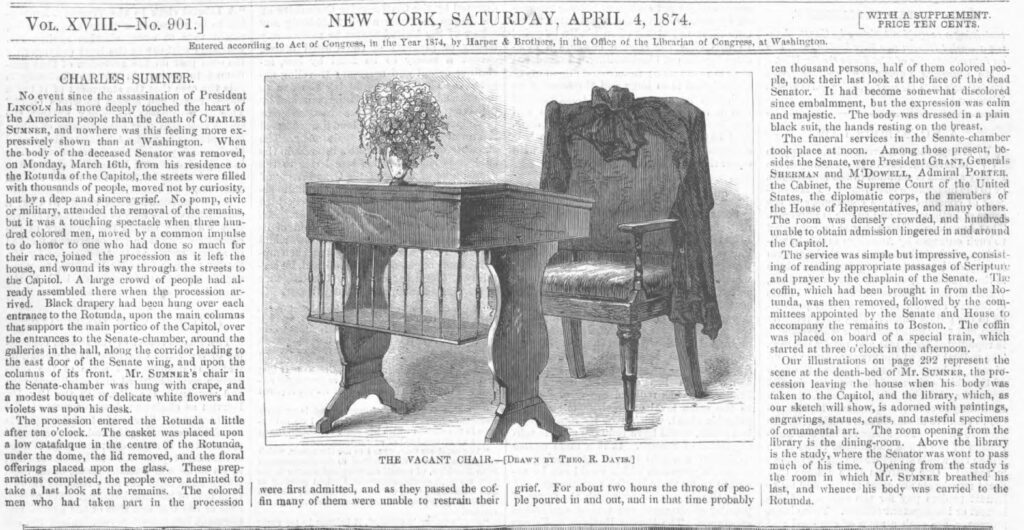

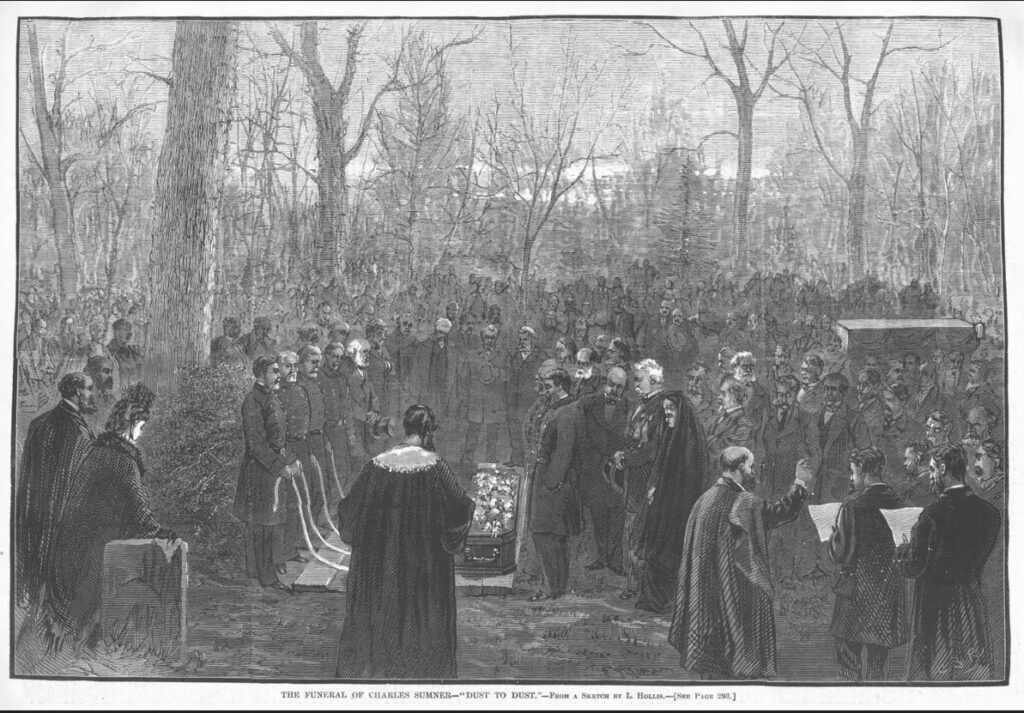

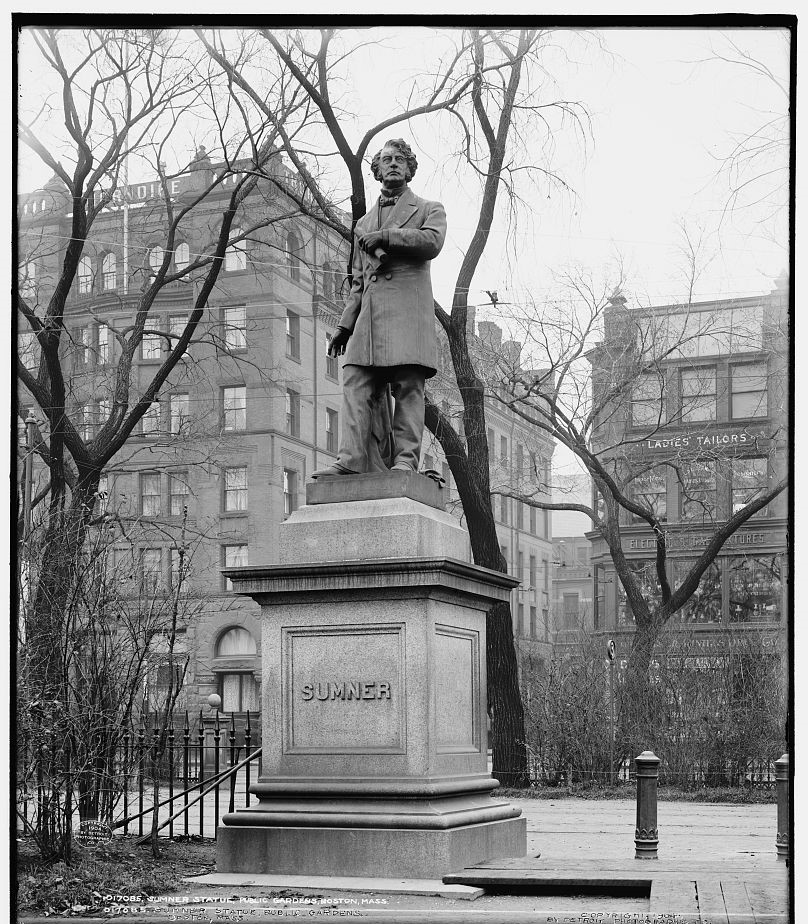

150 years ago today U.S. Senator Charles Sumner died in his Washington, D.C. home. He had represented Massachusetts in the Senate since 1851. In its March 28, 1874 issue Harper’s Weekly praised Mr. Sumner for his strong anti-slavery leadership:

CHARLES SUMNER.

MR. SUMNER leaves no public man behind him with so close a hold upon the heart of the country. He was the last of the great triumvirate of antislavery Senators who succeeded that other trio of the earlier and darker epoch of which we speak in another column of this paper. The work of the later three, SEWARD, CHASE, and SUMNER, was incomparably greater and more beneficent than that of WEBSTER, CLAY, and CALHOUN. It is a curious fact that Mr. SUMNER took his seat in the Senate on the day that Mr. CLAY, the last of the elder three, left it forever. The two men typified the two eras of our politics. HENRY CLAY was the great compromiser. CHARLES SUMNER was one of the most uncompromising men that ever lived. The courtly, gay, plausible, fascinating cavalier, “HARRY of the West,” broken, saddened, and disappointed, faltered out of the chamber, and CHARLES SUMNER, young, towering in form, dauntless in mien, the indomitable Puritan, conscience incarnate in politics, entered, and the new and better Union entered with him. The very qualities in him that so often offended were indispensable to the time and the work. Iconoclasm like his was as much needed among the long-worshiped idols of the old temple of slavery as ever it was among the images upon which CROMWELL’S Ironsides fell.

That stern refusal to wince or bend, which opposed itself to the slave power as a cliff of granite fronts the wildest sea and dashes it into futile froth, was the great and memorable service of CHARLES SUMNER to his country. When slavery in Congress encountered him, it met for the first time that North, that American conscience, that American will, which was at last to overthrow it utterly, and redeem and regenerate the country. For the first time in the national arena slavery found itself opposed by a spirit as resolute and haughty as its own. It tried every means to subdue it, and tried in vain. By culture and taste and temperament Mr. SUMNER was peculiarly sensible to that social blandishment in which Southern society excelled, and which made Washington a Capua to many hardy Northern warriors. They came, perhaps, from some secluded rural home, unused to the charms and forces of society. Bashful in the new scene, and ill at ease, they found the most welcome relief amidst the graceful delight of drawing-rooms and in the frank hospitality of dining-rooms in which their pleasure and comfort seemed to be the chief study. In those magic circles the lines of political duty, the sense of right and wrong, which in the quiet home or among cool New England hills were so clear and positive, wavered and shifted, and often glimmered quite out of sight. The lotus was eaten at those feasts, SAMSON was shorn, and honest folks at home wondered what nepenthe in the air of Washington drugged the Northern brain and dulled its conscience. No man was more thoroughly equipped to enjoy all this to the utmost than SUMNER, and no influence in public affairs is more subtle and effective with men of his temperament. But he knew the Lamia, and he did not yield.

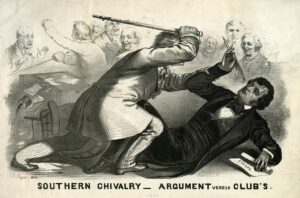

And as it could not seduce, neither could it terrify him. He stood for years in the capital of the country – to our bitter shame a slave city – and he thundered against slavery words which were blows. His speeches were not bursts of rhetoric; they were, like those of DEMOSTHENES, orations. The trained advocates of slavery and its mere attorneys were amazed at the comprehensiveness of discourses that left them no escape, left them, indeed, only rage and denunciation. And long afterward, when the ablest lawyer in the Senate, REVERDY JOHNSON, was preparing the speech in which he justified his vote upon emancipation, he carefully studied all of SUMNER’S orations as the completest body of history and argument upon the whole subject. The hostility of slavery took its natural form. Often for months it was known, and Mr. SUMNER knew, that his life was in constant danger; and during the heat of the Kansas debate a few friends from Kansas then in Washington, who were aware of his personal peril, unknown to him, daily followed him when he left his house, armed – as he never was or would be – for his protection. At last slavery, by the hand of PRESTON BROOKS, struck him the blow that it hoped would be fatal. But after a long and weary struggle his sturdy constitution seemed to have thrown off all serious effects of it, and after resuming his seat in the Senate with a speech that showed all the old vigor, he bore his part in the great and final conflict. But although he lived eighteen years after BROOKS’S assault, it was clear to him toward the end, and to his friends, that he had never wholly rallied from the blow.

The hostility of foes was not all that he withstood. His political and even many of his personal friends were impatient with him for the injury to the common cause which they feared from what they thought his want of moderation and tact. But those were his inestimable qualities, for they not only showed to slavery, as we said, the face of its real foe and future victor, but they stimulated and confirmed Northern sentiment by the spectacle of its uncompromising personification. There were censures of his taste, of his epithets, of his rhetoric, of his style, while he was doing a giant’s work in rousing and saving a nation. How many a critic points out the defects of St. Peter’s! And St. Peter’s remains one of the grandest temples in the world. He loved duty more than friendship, and he feared dishonor more than any foe. He measured truly the real forces around him, and he saw more clearly than any American statesman that ever lived the vital relation between political morality and national prosperity. The great acts of Republican legislation are thoroughly informed by the spirit of which he was the most fervent and comprehensive political representative. “Why, Mr. SUMNER, I am only six weeks behind you,” Mr. LINCOLN said to him, during the war. It was most fortunate for him that his career was cast at a time and upon a scene for which he was especially fitted, and he lived for a quarter of a century in the full view of friends and foes, doing his duty without a stain upon his fame. CHARLES SUMNER hated slavery, and slavery hated him. And because, in the long and terrible contest, he was so true and so steadfast, panoplied in principle, armed at every point, strong as conscience and pure as childhood, his name will be honored in the land so long as the descendant of a slave remains, or America loves liberty.

“Whom neither shape of danger can dismay,

Nor thought of tender happiness betray;

Who, not content that former worth stand fast,

Looks forward, persevering to the last,

From well to better, daily self-surpast;

Who, whether praise of him must walk the earth

Forever, and to noble deeds give birth,

Or he must fall,to sleep without his fame,

And leave a dead,unprofitable name,

Finds comfort in himself and in his cause:

And while the mortal mist is gathering, draws

His breath in confidence of Heaven’s applause.”

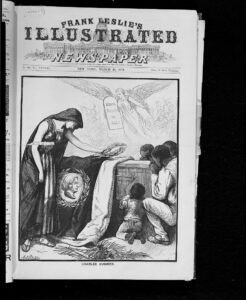

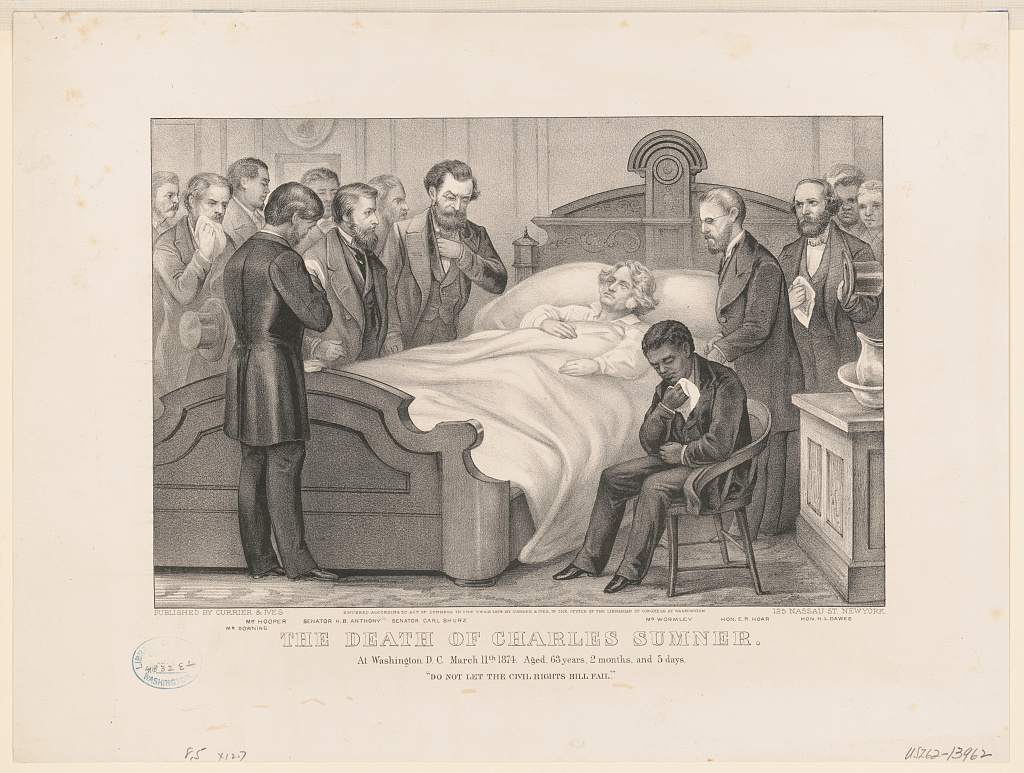

In Richmond, Virginia the Daily Dispatch reported Mr. Sumner’s death om page one of its March 12th issue. The TIMON correspondent telegraphed the news. The senator apparently suffered from organal pectoris and was in such great pain from about 11:00 PM on March 10th that his doctors kept him on opiates. Most members of Congress called at his house during March 11th. According to TIMON, about the last words Sumner spoke were to Representative Dawes: “Tell Emerson I love and revere him.” The Harper’s Weekly portrait of Sumner above shows that on his deathbed he also said something like, “Do not let the civil rights bill fail.” This is backed up in a paragraph from the March 13th issue of the Daily Dispatch, which said Senator Sumner spoke the words to Representative Ebenezer R. Hoar. The Dispatch considered the civil rights bill a “new firebrand.”

Probably the most notorious event in Mr. Sumner’s Senate career occurred during the Bleeding Kansas debate. On May 19 and 20, 1856 Sumner delivered his “Crime Against Kansas” speech in which he denounced the Kansas – Nebraska Act and his colleagues who wrote the legislation – Stephen A. Douglas and South Carolinian Andrew Butler. Sumner said Butler’s mistress was the harlot Slavery and made fun of Butler’s speaking ability. Butler had recently suffered a stroke. Senator Butler was not present during the speech. Congressman Preston Brooks, Butler’s cousin, took offense, and on May 22nd Brooks severely injured by repeatedly caning Sumner on the head . It is said the incident further polarized the United States in the run-up to the Civil War. In its March 14, 1874 issue the Daily Dispatch criticized northern newspapers that used their eulogies of Sumner to rehash the caning and to stir up the North against the South.