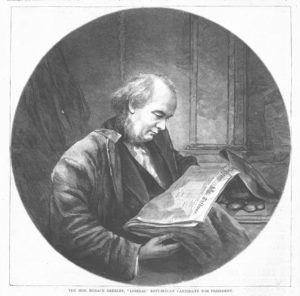

1872 was another presidential election year in the United States. Would the Republican incumbent, General Ulysses S. Grant be reelected? President Grant was popular, even though his Administration was involved in several scandals. One possible impediment to Grant’s reelection was that not all non-Democrats wanted a second term for the president. The Liberal Republican party was formed in 1870. At the party’s convention in Cincinnati in May 1872 the Liberal Republicans chose newspaper publisher Horace Greeley to be its nominee. Harper’s Weekly opposed the Liberal Republicans’ challenge to Grant, but it did give Horace Greeley his due as a self-made man.

From the May 18, 1872 edition of Harper’s Weekly:

HORACE GREELEY.

The man whom the “Liberal” Republicans at Cincinnati selected to be their standard-bearer in the ensuing political campaign is in every sense of the word “self-made.” His father, ZACCHEUS GREELEY, was a poor New Hampshire farmer, who was only able to give him the advantages of a common-school education, and very little of that. But his energy, ambition, and capacity supplied all deficiencies, and enabled him to push his way from obscurity to the prominent position he now occupies.

HORACE GREELEY was born at Amherst, New Hampshire, on the 3d of February, 1811. He was a rather feeble child, and for years suffered from want of physical strength rather than from any positive disease. He lived with his parents in New Hampshire until the 1st of February, 1821, going to school a little and working on the farm a great deal, when, in consequence of his father’s failure and the enforced sale of his farm, the whole family went to West Haven, Vermont. Here he was distinguished at school by the readiness with which he absorbed knowledge.

After about five years of farm experience in West Haven, where each season proved a worse failure than its predecessor, he became an apprentice in a newspaper office, The Northern Spectator, at East Poultney, Vermont.

Mr. GREELEY remained four years at East Poultney, doing the hard work of an apprentice with credit. He went thence to visit his father in Chautauqua County, New York, and subsequently worked at his trade in Jamestown, Lodi [now Gowanda], and Erie. But work in small towns was scarce, and, after vain searching for permanent employment, the young printer started for New York city. He went by canal-boat from Buffalo to Schenectady, and thence footing it over the old turnpike, he reached Albany, where he took passage in a tow-boat for New York. Here he landed August 17, 1831. Work was the thing first in order, and after a short search he found it with a printer in Chatham Street.

Mr. GREELEY made his first business venture in New York as a partner in a daily paper called the Morning Post, started January 1, 1833, by Dr. H.D. SHEPARD. The paper lived about a month. In March, 1834, he made his first visible mark in journalism by issuing the New Yorker, a large and handsome weekly paper devoted to literature and news. Here, for the first time, he began to use a pen as well as types, and in a short time became widely known as a writer. Two years after starting this paper Mr. GREELEY married. Five children have been born to him, of whom two boys and one girl died at early ages.

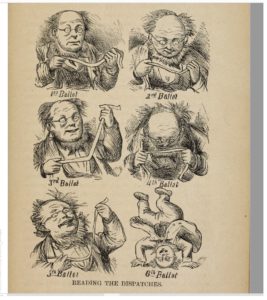

reading the ticker tape

While publishing the New Yorker Mr. GREELEY made his début as a political writer in 1838, on a small campaign paper called the Jeffersonian, and in the HARRISON campaign as the editor of the Log-Cabin. On the 10th of April, 1841, the day on which the people observed the funeral of President HARRISON, Mr. GREELEY, almost moneyless and unaided, issued the first number of the New York Tribune.

In 1848 Mr. GREELEY was elected to Congress to fill a vacancy, and served from December 1 of that year till March 4, 1849. His Congressional career was not a brilliant one, and was chiefly distinguished by his vigorous assault upon the mileage system. In 1850 he published a volume of political lectures and essays, under the title of “Hints toward Reform.” The following year he made a voyage to Europe, and during his visit to England served as a juryman at the Crystal Palace Exhibition. On his return he published a volume entitled “Glimpses at Europe.” His first important contribution to political literature was his “History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension and Restriction from 1787 to 1856,” the year of its publication. In 1859 Mr. GREELEY paid a visit to California, traveling overland across the plains.

During the political excitement which immediately preceded the outbreak of the Southern rebellion, Mr. GREELEY, in common with many prominent members of the Democratic party, took the ground that the disaffected States should be permitted to depart in peace, if a majority of their inhabitants desired the separation, and form a new government for themselves. On the actual occurrence of hostilities, however, he gave the national administration a warm support; though several times during the progress of the war, when disasters had overtaken the national forces in the field, and the issue of the campaign was wavering in the balance, he appeared to lose heart and to be ready to give up the contest on almost any terms that could be obtained. It is fortunate for the nation that his views were not shared by the dominant party at the North; and doubtless Mr. GREELEY himself is now well satisfied that his counsels were disregarded.

To comment at length upon Mr. GREELEY’S political career would be beyond the purpose of this sketch. Our readers can not fail to remember his famous tour through the Southern States a few months ago, when he shook hands with JEFFERSON DAVIS, and made conciliatory speeches to Southern people who have not become reconciled to the issue of the war nor to the amendments to the Constitution. The tour looked amazingly like a part of an electioneering programme, like Johnson’s famous “swinging round the circle,” or General Scott’s equally famous “military tour of inspection” in 1852.

It was evident several weeks before the meeting of the Cincinnati Convention that Mr. GREELEY would be a candidate for nomination; but, though his strength and popularity with certain classes were allowed — and it was supposed he would receive a large complimentary vote — very few outside of the circle of his immediate friends and admirers supposed he would obtain the first place on the ticket. The Hon. CHARLES FRANCIS ADAMS was regarded as by far the strongest and most eligible man for the position; and this opinion remained unchanged until a short time before the balloting commenced. On the first five ballots Mr. ADAMS took the lead, but without securing the number of votes necessary to a choice. TRUMBULL and DAVIS were nowhere, from the start. The contest lay between ADAMS and GREELEY. At the

close of the sixth ballot the poll stood as follows:

Adams, …………… 324 Davis…………….6

Greeley……………. 332 Chase…………… 32

Trumbull…………. 19 Palmer…………..1

Before the result was announced, the Illinois delegation changed to GREELEY, with the exception of one member, who insisted that his vote should stand for TRUMBULL. Several other States followed the example of Illinois, and the final result was announced as follows:

Whole vote…………. 714 Adams…………… 187

Necessary to a choice. 358 Greeley…………. 482

A motion to make the nomination unanimous was lost. The Convention nominated Mr. GRATZ BROWN, of Missouri, for Vice-President on the second ballot, and then adjourned sine die.

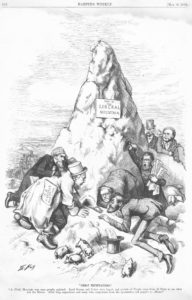

The Liberal Republican platform called for civil service reform in its fifth plank, and that required a presidential term limit of one term:

“Fifth: The Civil Service of the Government has become a mere instrument of partisan tyranny and personal ambition and an object of selfish greed. It is a scandal and reproach upon free institutions and breeds a demoralization dangerous to the perpetuity of republican government. We therefore regard such thorough reforms of the Civil Service as one of the most pressing necessities of the hour; that honesty, capacity, and fidelity constitute the only valid claim to public employment; that the offices of the Government cease to be a matter of and patronage, and that public station become again a post of honor. To this end it is imperatively required that no President shall be a candidate for re-election.”

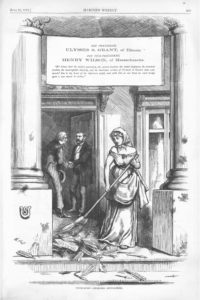

As expected, the Republicans nominated Ulysses S. Grant for a second term as president at the convention held in Philadelphia June 5th and 6th, although they replaced Schuyler Colfax with Senator Henry Wilson from Massachusetts.

The majority of Democrat delegates opted for the anybody but Grant philosophy. At their convention in Baltimore July 9-10 they overwhelmingly chose Greeley and Gratz Brown as their nominees for president and vice-president and adopted the Liberal Republican platform. Wikipedia summarizes the strategy and the inherent tension:

“Accepting the Liberal platform meant the Democrats had accepted the New Departure strategy, which rejected the anti-Reconstruction platform of 1868. They realized that to win the election they had to look forward, and not try to re-fight the Civil War. They also realized that they would only split the anti-Grant vote if they nominated a candidate other than Greeley. However, Greeley’s long reputation as the most aggressive antagonist of the Democratic Party, its principles, its leadership, and its activists, cooled Democrats’ enthusiasm for the presidential nominee.

“Some Democrats were worried that backing Greeley would effectively bring the party to extinction, much like how the moribund Whig Party had been doomed by endorsing the Know Nothing candidacy of Millard Fillmore in 1856, though others felt that the Democrats were in a much stronger position on a regional level than the Whigs had been at the time of their demise, and predicted (correctly, as it turned out) that the Liberal Republicans would not be viable in the long-term due to their lack of distinctive positions compared to the main Republican Party. A sizable minority led by James A. Bayard sought to act independently of the Liberal Republican ticket, but the bulk of the party agreed to endorse Greeley’s candidacy. The convention, which lasted only six hours stretched over two days, is the shortest major political party convention in history.”

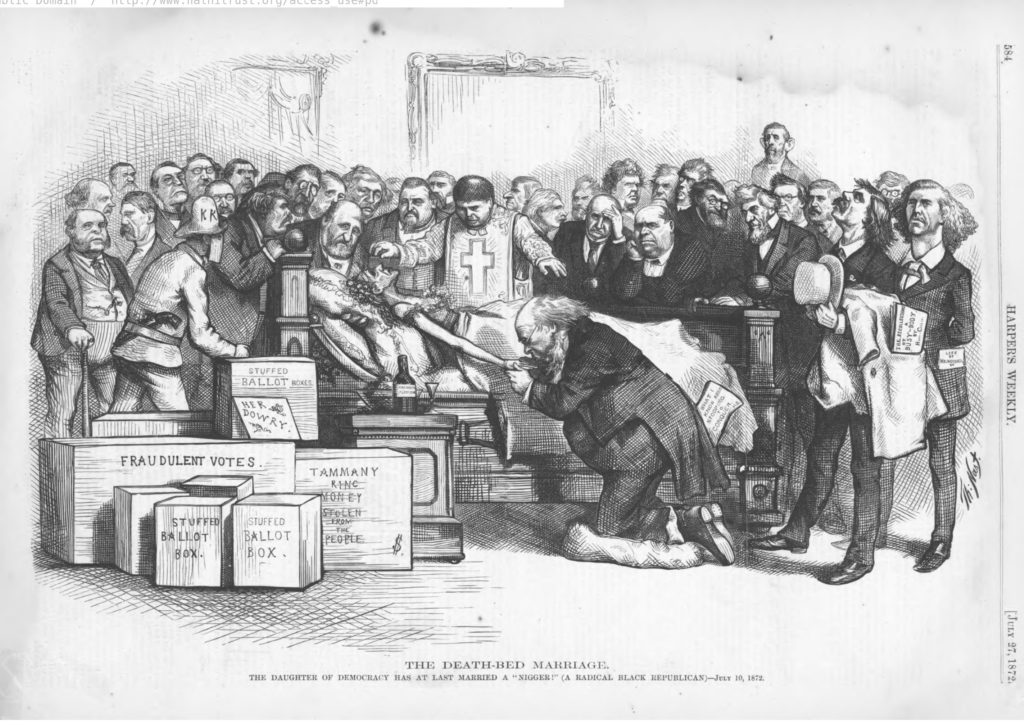

Harper’s Weekly and its cartoonists suggested uniting with Democrats meant uniting with The Ku Klux Klan and Tammany Hall.