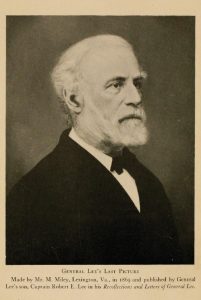

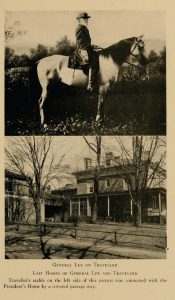

It was a damp, chilly afternoon in Lexington, Virginia. A heavy rain set in that eventually resulted in some severe flooding. September 28, 1870 was a long day for Robert E. Lee, the president of Washington College. According to Colonel William Preston Johnston, Mr. Lee ended his work day with a three hour church meeting:

“Wednesday, September 28, 1870, found General lee at the post of duty. In the morning he was fully occupied with the correspondence and other tasks incident to his office of president of Washington College, and he declined offers of assistance from members of the faculty, of whose services he sometimes availed himself. After dinner, at four o’clock, he attended a vestry-meeting of Grace (Episcopal) church. The afternoon was chilly and wet, and a steady rain had set in, which did not cease until it resulted in a great flood, the most memorable and destructive in this region for a hundred years. The church was rather cold and damp, and General Lee, during the meeting, sat in a pew with his military cape cast loosely about him. In a conversation that occupied the brief space preceding the call to order, he took part, and told with marked cheerfulness of manner and kindliness of tone some pleasant anecdotes of Bishop Meade and Chief-Justice Marshall. The meeting was protracted until after seven o’clock by a discussion touching the rebuilding of the church edifice and the increase of the rector’s salary. General Lee acted as chairman, and, after hearing all that was said, gave his own opinion, as was his wont, briefly and without argument. He closed the meeting with a characteristic act. The amount required for the minister’s salary still lacked a sum much greater than General Lee’s proportion of the subscription, in view of his frequent and generous contributions to the church and other charities, but just before the adjournment, when the treasurer announced the amount of the deficit still remaining, General Lee said in a low tone, ‘I will give that sum.’ He seemed tired toward the close of the meeting, and, as was afterward remarked, showed an unusual flush, but at the time no apprehensions were felt. …

After the church meeting Mr. Lee went home. As his wife Anna Custis Lee wrote, the general was literally speechless:

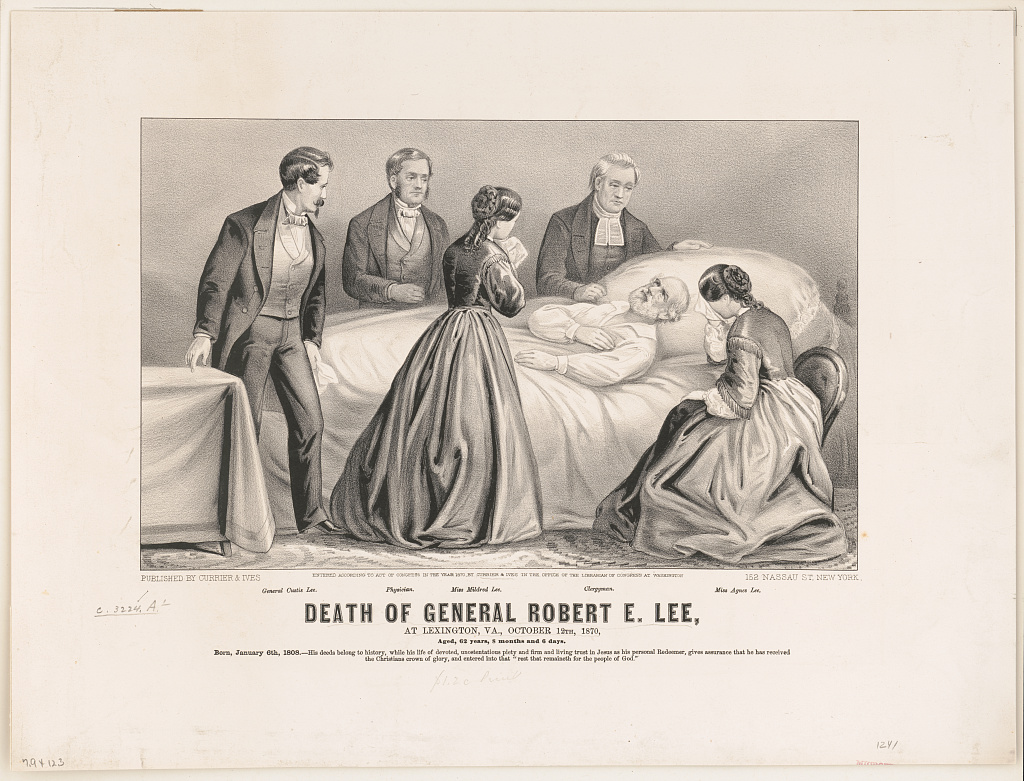

“…My husband came in. We had been waiting tea for him, and I remarked: ‘You have kept us waiting a long time. Where have you been?’ He did not reply, but stood up as if to say grace. Yet no word proceeded from his lips, and he sat down in his chair perfectly upright and with a sublime air of resignation on his countenance, and did not attempt to a reply to our inquiries. That look was never forgotten, and I have no doubt he felt that his hour had come; for though he submitted to the doctors, who were immediately summoned, and who had not even reached their homes from the same vestry-meeting, yet his whole demeanour during his illness showed one who had taken leave of earth. He never smiled, and rarely attempted to speak, except in dreams, and then he wandered to those dreadful battle-fields. Once, when Agnes urged him to take some medicine, which he always did with reluctance, he looked at her and said, ‘It is no use.’ But afterward he took it. When he became so much better the doctor said, ‘You must soon get out and ride your favorite gray!’ He shook his head most emphatically and looked upward. He slept a great deal, but knew us all, greeted us with a kindly pressure of the hand, and loved to have us around him. For the last forty-eight hours he seemed quite insensible of our presence. He breathed more heavily, and at last sank to rest with one deep-drawn sigh. And oh, what a glorious rest was in store for him!”

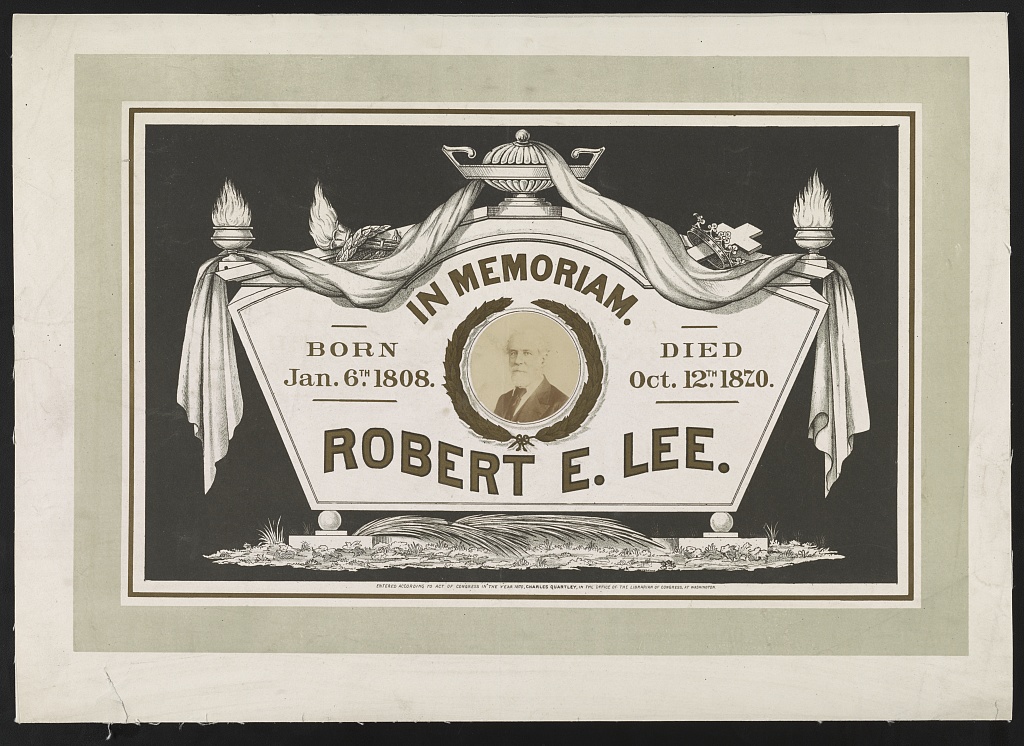

General Lee breathed his last on October 12th. Thanks to the telegraph, the news spread quickly. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch October 13, 1870:

The News Of The Death Of General Lee

The tidings of the death of Gen. Robert E. Lee reached Richmond by telegraph at nightfall yesterday. The brief telegram containing the sad intelligence brought sorrow to the heart of every man, woman, and child, in the city, and ere an hour passed, the whole community was shrouded in gloom. All seemed to have a sense of personal bereavement, and everywhere was manifested a desire to pay a fitting tribute of respect and affection to the memory of the departed patriot.The Chamber of Commerce had just assembled in annual meeting when the news was announced. No business was done except the adoption of the following resolution:”That this Chamber of Commerce recommend to its members and the citizens generally to close their places of business and place crape upon their doors during the day tomorrow (13th instant), in token of the general grief and as a tribute to the memory of the good and great man who has fallen in the midst of his usefulness and his honors.”The Chamber then adjourned to meet on Wednesday, the 19th instant.The action of this representative body of our mercantile community was spontaneous, and just what might have been expected of an assemblage of Virginia gentlemen stricken by the saddest of news; and the sentiment which prompted it will find an echo in every breast. No words of ours are necessary to secure the strict observance of the recommendation.The Governor will to-day communicate officially to the General Assembly the news of General Lee’s death, and in all probability that body will set apart a day to be observed as one of mourning throughout the Commonwealth. Virginia’s voice will doubtless find expression in the request that the remains of her noblest and most honored son shall he brought to the capital and interred where lie so many of her heroic dead – at Hollywood.The bells on all the public buildings in the city will be tolled from sunrise to sunset to-day as a tribute of respect, and the City Council will hold a meeting at 5 o’clock P. M. to take action in reference to the public loss.

________________________

Horace Greeley really annoyed the Richmond Dispatch when he apparently opined that flags should not be flown half-mast in General Lee’s honor. In its October 24th issue the Daily Dispatch said that future historians would look kindly on General Lee – just like a contemporary editorial from London:

Greeley excuses himself for justifying Mr. Boutwell and his Savannah understrapper in refusing to allow the United States flag to fly at half-mast upon the occasion of the death of General Lee by pleading that that flag represents “the whole country” that General Lee won his fame in attempting to humble it; and that he (Greeley) cannot “consent that a false estimate” of General Lee’s errors “shall pass into history.” Thus spoke and wrote the great Dr. Samuel Johnson, of Washington, and the other “rebels” who fought the war of American independence. Thus spoke and wrote the British loyalists of the seventeenth century concerning John Hampden, Algernon Sidney, and Oliver Cromwell. But history to-day speaks the praises of all these men. A Carlyle champions Cromwell, a Macaulay extols Hampden and Sidney, and every historian, British and American, lauds the “Cincinatus of the West.” So shall it be, oh, mole-eyed Greeley, with the fame of Robert E. Lee. It will grow brighter and brighter as the coming centuries fall into line with the years “beyond the flood.” The voice of contemporaneous historians residing in England is some indication of what the verdict of those separated from us by time instead of distance will be. Even as we write we come across the following discriminating article, copied from the London Standard. Read it, all ye puny tricksters who set up your little parasols between the sun and the earth, and understand how much light you will be able to shut out from the future historian – how easy you will find the task of preventing the truth from “passing into history”: “The announcement that General R. E. Lee has been struck down by paralysis, and not expected to recover, will be received, even at this crisis, with universal interest, and will everywhere excite a sympathy and regret which testify to the deep impression made on the world at large by his character and achievements. Few are the generals who have earned, since history began, a greater military reputation; still fewer are the men of similar eminence, civil or military, whose personal qualities would bear comparison with his. The bitterest enemies of his country hardly dared to whisper a word against the character of her most distinguished general; while neutrals regarded him with ah admiration for his deeds and a respect for his lofty and unselfish nature which almost grew into veneration, and his own countrymen learned to look up to him with as much confidence and esteem as they ever felt for Washington, and with an affection which the cold demeanor and austere temper of Washington could never inspire. The death of such a man, even at a moment so exciting as the present, when all thoughts are absorbed by a nearer and present conflict, would be felt as a misfortune by all who still retain any recollection of the interest with which they followed the Virginian campaigns, and by thousands who save almost forgotten the names of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the Wilderness and Spotsylvania. Truer greatness, a loftier nature, a spirit more unselfish, a character purer, more chivalrous, the world has rarely if ever, known. Of stainless life and deep religious feeling; yet free from all taint of cant and fanaticism and as dear and congenial to the Cavalier Stuart as the Puritan Stonewall Jackson; unambitious, but ready sacrifice all at the call of duty; devoted to his cause, yet never moved by his feelings beyond the line prescribed by his judgment; never provoked by just resentment punish wanton cruelty by reprisals which would have given a character of needles savagery to the war – North and South owe a deep debt of gratitude to him, and the time will come when both will be equally proud of him. And well they may, for his character and his life afford a complete answer to the reproaches commonly cast on money-grubbing, mechanical America. A country which which has given birth to like him him, and those who follow him, may look the chivalry of Europe in the face without shame; for the fatherlands of Sidney and Bayard never produced a better solider, gentlemen, and Christian than General Robert E. Lee.”

An editorial from New York City wasn’t as complimentary. From the October 29, 1870 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

ROBERT E. LEE

ROBERT E.LEE was undoubtedly an amiable man and a good soldier. But his career, in that part of it which concerns the whole country, was an illustration of an apparently fatal weakness of character. He was bred to the army, and served as an engineer in Mexico with great distinction, and subsequently in a cavalry command. Upon the fall of Sumter, the first time that the flag of his country had been fired upon with doubtful result, he resigned his commission, on the 20th of April, 1861, saying that except in defense of his native State he hoped never again to draw his sword. Despite this hope, however, he went immediately to Richmond, where, two days afterward, he was appointed General of the Virginia troops, and on the 10th of May Major-General of the rebel army. From that time he was the most popular man in the Confederacy. He was passionately extolled by his Southern associates, and the Copperhead and the Copperhead papers in the North were never weary of applauding the “great captain” and “the Christian gentleman.”

His military skill was conceded by his ablest opponents. But he kept himself carefully aloof from politics, confining himself closely to his military duties. It will not, however, be forgotten that the suffering of the Union prisoners at Belle Isle was almost visible from his headquarters in Richmond, and that the tortures of Andersonville were not stopped by him, nor, so far as we are aware, condemned by him. Personally courteous, and in the field honorably considerate of friend and foe, his indifference to the fate of the Union prisoners may have been due to incredulity, or to a feeling that he was not responsible. Indeed, notwithstanding that he passed immediately from the national army to that of the rebels, his interest in the rebellion seems to have been reluctant and ex officio. Trained in the sophistry of State sovereignty he thought it his duty to “to go with his State,” but saw no reason that his State should go. His services being required by the authority to which he thought them due, he performed the tasks allotted him as well as he could. “I recognize no necessity for this state of things,” and with a fatal inability to perceive, what he yet seems always to have vaguely felt, the consequent immorality of his position, he continued to conduct the operations of a war which seemed to him needless.

If that war had been in defense of his country, if it had been a rising against intolerable oppression, if its object had been to assert and maintain threatened freedom, his obedience to such an authority would have been commendable. But it was a war to destroy a nation, and instead of a rising against oppression, it was an effort to overthrow a great government, solely because it seemed to favor lawful liberty. To such a cause he gave his sword, because he thought that Virginia had a right to command it! Was his moral judgment, was his manhood, subject to his State? A man may be amiable, courteous, and refined, a brave and skillful soldier, unselfish, and modest, but if in the crucial moment of his life he consents to fight in a war of which he sees no necessity, and the malign purpose of which is but too plain, he consents to cloud his name forever as that of an amiable man whose weakness is virtual crime. It is in vain that we say General LEE thought that he ought to go with his State, for no man whom history can respect thinks that he ought to go with his State or with his country for an ignoble purpose. If he did not see that purpose as ignoble, his confusion is even the more evident; for he was then ignorant of what was known to every man, and of what had been loudly and widely declared by the second officer of the Government which he obeyed.

From the day that he surrendered and his cause was lost General LEE lived quietly withdrawn from the public eye. Apparently regarding events as a soldier and not as a politician, he did not think it honorable to try to thwart the results of a victory which he had vainly sought to prevent. His personal generosity and kindliness, and the modesty of his retirement, had greatly softened public feeling, and he has been regarded with the pity that always attends sincere self-sophistication. But in the warmest eulogies that have been made of him, however, there is a tone of conscious apology. He was in no sense a great man, but he may be called truly unfortunate. His name will be remembered as that of a chief leader of one of the worst causes in history, yet a weak man, called to deal with events which he could neither clearly comprehend nor control.

Colonel Johnston’s book said that one of Robert E. Lee’s last earthly acts was to contribute some money to his church, but of course that was 150 years ago. According to the Episcopal Church website, the church in Lexington changed its name from R.E. Memorial Church to Grace Episcopal Church three years ago. Scroll to bottom of the web page if you’d like to “♥ Give to The Episcopal Church”

I enjoyed learning more about Robert E. Lee’s last years at a lecture reproduced on Youtube. Gettysburg National Military Park Ranger Matt Atkinson is a big fan of the general.

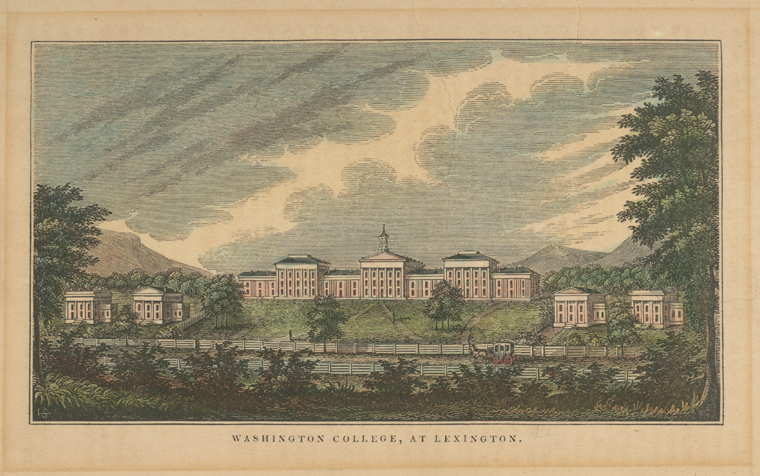

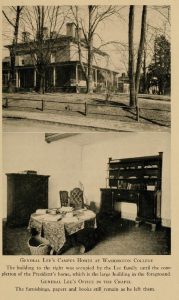

Last evening I read Allen C. Guelzo’s “The Mystery of Robert E. Lee” in the October 5, 2020 issue of National Review (pages 33-36). Robert’s father, “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, behaved recklessly and abandoned of his family when Robert E. was six-years old. The trauma created three great drives in Robert’s psyche – desires for perfection, independence, and security. Those forces “governed the extraordinary skill with which he managed Confederate military affairs.” His preeminence in the CSA did not make him happy; that only came when he used the three forces at as president of Washington College, “where he would find independence to run matters as he saw fit, find security for himself and his family, and find perfection in what he could demand of his students.” I got a little nervous when I read that Mr. Lee abolished the college rule book, the only rule was to behave as a gentleman, which made President Lee the only lawgiver and judge. I’m kind of used to believing in the U.S. we live under a written constitution.

I’m guessing the “nearer and present conflict” mentioned in the London editorial is the Franco-Prussian war, which has even been dominating the pages of America’s Harper’s Weekly.

________________________________