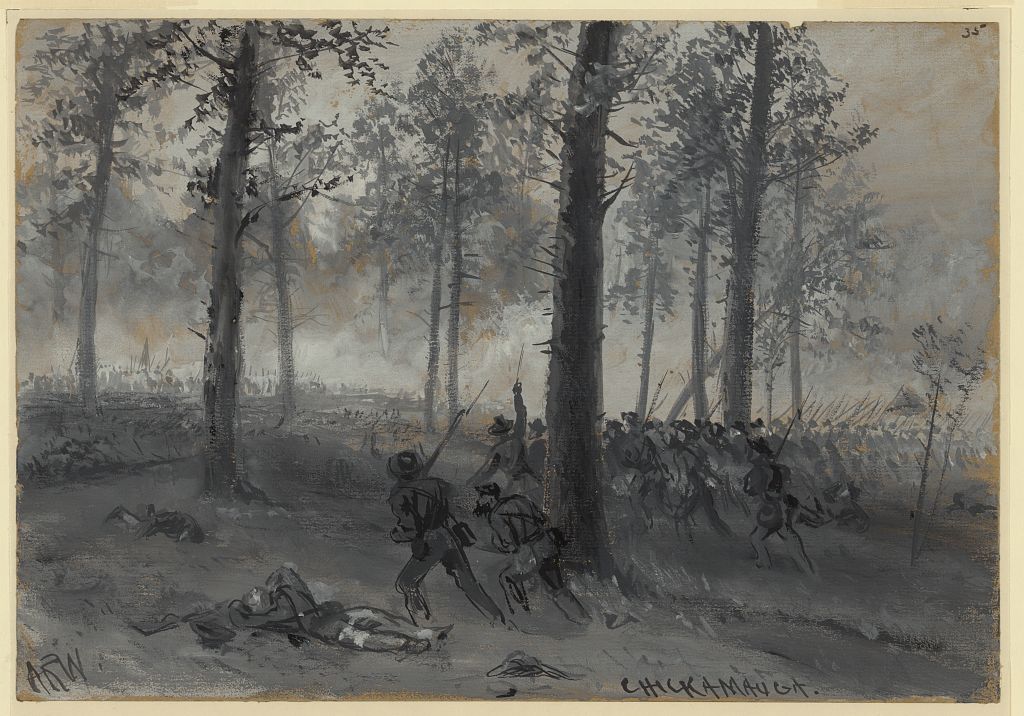

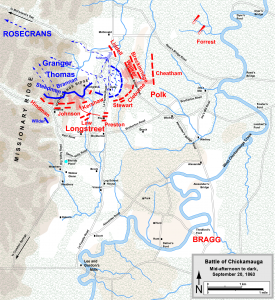

I first knew of him as “The Rock of Chickamauga.” In September 1863 Union General George H. Thomas and his men held off the Confederate Army of Tennessee while about a third of the Union Army of the Cumberland was fleeing back to Chattanooga from the fight in northern Georgia. Thanks to their determined defense the Union army was able to regroup enough to fight another day, with reinforcements. Of course, there was much more to George Thomas’s life and career than the Battle of Chickamauga. His career was all army from his West Point graduation in 1840 through the Civil War and beyond. His last post was as commander of the Military Division of the Pacific, where he died in San Francisco on March 28, 1870. In response to news of his death, a New York City newspaper published a brief bio of the native Virginian. The next week it described the funeral and burial services. At least three of Thomas’s fellow generals from the Chattanooga campaign of October and November 1863 attended – the U.S. president, the army’s general-in-chief, and Joe Hooker.

From the April 16, 1870 edition of Harper’s Weekly:

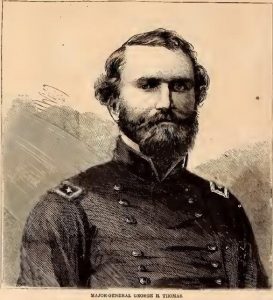

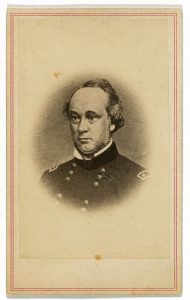

GEN. GEORGE H. THOMAS.

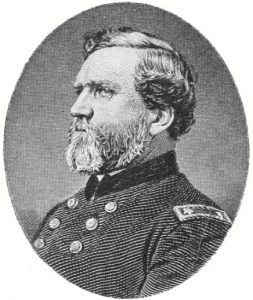

On the 29th of March the sorrowful intelligence was communicated to us of the death of Major-General GEORGE H. THOMAS. He died at eight o’clock on the 28th from a stroke of apoploxy, at San Francisco, his post of duty. General THOMAS was born on July 31, 1816, in the county of Southampton, Virginia. In his early boyhood he accepted a subordinate position under his uncle, the clerk of the county, and at the same commenced the study of law. It is worthy of notice that he was a native of Virginia, belonging, as did General ROBERT E. LEE, to wealthy and respectable family of that State. Like General LEE, also, he was sent from Virginia to West Point, where he graduated June 30, 1840, ranking twelfth in a class of forty-two.

His military career previous to our Civil War is soon told. Immediately after his graduation at West Point he took part in the Indian campaign in Florida, serving as Lieutenant. He took a prominent part in the Mexican War, and for gallant conduct in the several conflicts at Monterey, on the 21st, 22d, and 23d of September 1846, was brevetted Captain. February 23, 1847 he was brevetted Major “for gallant and meritorious conduct in the Battle of Buena Vista.”

November, 1860, found THOMAS in Texas. General TWIGGS had surrendered, and Major THOMAS at Carlisle Barracks took command of the Sixth Cavalry, and entered into the great conflict for the preservation of the Union. We do not purpose in this brief sketch to follow his military career during the Civil War in all its details. Unlike General LEE, he did not consider it his duty to sacrifice his allegiance to the nation to that which he owed to Virginia. On May 3, 1861, we find him Colonel of the Fifth Cavalry (the old Second), in the place of General LEE, who had resigned. He commanded the first brigade of General PATTERSON’s army of Northern Virginia until August 26, 1861, when he was made Brigadier-General of Volunteers, and ordered to Kentucky. Thenceforth his career was eminently successful, and in many respects more remarkable than that of any other Federal general during the war.

General THOMAS was never defeated. After his victory over General ZOLLICOFFER at Mill Spring, in January, 1862, he moved forward and, after the fall of Fort Donelson, occupied Nashville. On the second day of the battle of Pittsburgh Landing he commanded the reserve of the Union army. He was made a Major-General April 25, 1862, and at the close of the year we find him in command of a corps under ROSECRANS’s command. In the official report of the battle of Stone River General ROSECRANS alluded to General THOMAS as “true and prudent, distinguished in counsel and on many battle-fields for his courage.”

In the summer and autumn of 1863 General THOMAS especially distinguished himself in the Chattanooga campaign. But for his wise precautions ROSECRANS could never have concentrated his army at Chickamauga, and must have been overcome in detail by BRAGG. ROSECRANS would have it that BRAGG was retreating in confusion into Georgia. But THOMAS knew better. When the army was finally concentrated at Chickamauga General THOMAS commanded the left wing, which he held in position on the 19th of September, retrieving the battle which ROSECRANS had already given up as lost. In October THOMAS was assigned to the command of the Army of the Cumberland, succeeding ROSECRANS.

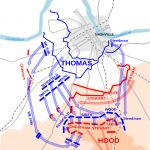

In the Atlanta campaign, early in 1864, THOMAS took a prominent part. After its successful completion General SHERMAN, setting out for his March to the Sea, sent THOMAS back to Nashville to attend to HOOD, who had succeeded General BRAGG. HOOD’S design was to compel SHERMAN’S retreat by a bold march northward, looking to the occupation of Nashville.

The result of the battle of Nashville, near the close of 1864, gave General THOMAS his most characteristic distinction. He will ever be known as “the hero of Nashville.” His patience before the battle, when the wiseacres at Washington were clamoring for an immediate advance on his part, was not less remarkable than his tactics on the battle-field after that [sic] he had mustered all his forces and entered upon the conflict. His victory over HOOD was the most complete victory of the war. HOOD’S forces were utterly demoralized, and the rebel power in the Southwest never recovered from the blow. For this THOMAS was made a Major-General in the regular army.

Since the close of the war General THOMAS has been assigned to department duty in Tennessee and Kentucky, and latterly California. During the few weeks preceding his death he enjoyed remarkably good health; but on the 28th, at half past five o’clock, P.M., he was seized with a fit of apoplexy while attending to business in his office. In less than three hours after the attack he died. His death is truly a national calamity. As a man and as a soldier his character is unreproached and irreproachable.

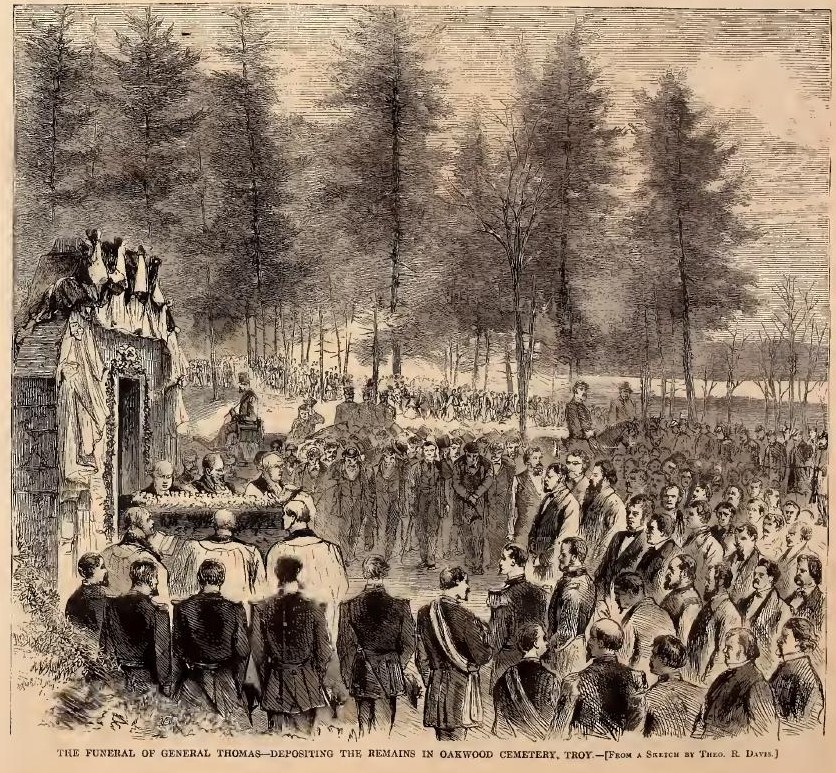

From the April 23, 1870 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

THE FUNERAL OF GEN. THOMAS.

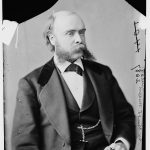

On the 8th inst. the remains of Major-General GEORGE H. THOMAS, the Hero of Mill Spring and Nashville, were buried with appropriate civil and military honors in Oakwood Cemetery, at Troy. The occasion drew together a vast concourse of people desirous of paying the last tribute of respect to one whose services to the Union will ever cause his memory to be held in the highest veneration by his countrymen. The funeral services were held in St. Paul’s Church, which was appropriately draped for the occasion. The remains of the lamented soldier, in a metallic burial casket, were deposited on a dais in front of the chancel. A ribbon of immortelles and wreaths of ivory were twined around the edge of the casket in California, and were deposited with it in the grave. As it lay in the chancel an elegant crown of evergreens and roses, surmounted by a cross of immortelles, was placed at the head, and a wreath of japonicas [my best guess] and lilies at the foot of the casket. A plain silver plate bore the simple inscription: “Gen. GEORGE HENRY THOMAS, U.S. Army. Born July 31, 1816. Died March 28, 1870.” President GRANT, General SHERMAN, and General HOOKER, and many other distinguished men were present to do honor to his memory.

The sketch underneath represents the scene in the cemetery at the moment of depositing the remains in the vault belonging to the family of the deceased soldier’s wife. The burial service was read by Bishop DOANE, after which the customary burial salute was fired by the United States Infantry, and the procession left the cemetery, each portion of it wheeling out of line on the return, as it reached its appropriate place. In the evening a funeral oration was delivered, in Dr. BALDWIN’S church, by General STEWART L. WOODFORD, on the life, character, and services of the late General, there having been, at the special request of Mrs. THOMAS, no panegyric or eulogy pronounced over the remains. After a rapid sketch of his military career the orator gave some interesting personal reminiscences of the General, which served to illustrate his character and show the estimate in which he was held by his soldiers. Silent, sedate, never familiar, though always kind, he had none of the petty arts and practiced none of the stage devices that sometimes attract a short-lived popularity. His men had always known him to be thoughtful of their wants and considerate of their comforts. He had never exacted from them useless work. He had never tolerated the slightest evasion of duty, from his brigadiers down to his orderlies. Always, when possible opportunity was afforded, he had visited the regimental hospitals and looked himself after the condition of the sick. Many a hospital steward and company cook in the old Cumberland Army remember the unexpected and personal inspection which the sick-quarters and the company kitchen received from the Major-General himself. And not soon will they forget how once his face hardened into a white heat of passion when he found that a drunken commissary had neglected to provide sufficient food, and how, taking out his penknife, he ripped off the fellow’s shoulder-straps, and simply said, “Go home, Sir, by the next train. You may do to feed cattle; you shall not feed my soldiers.” His soldiers called him “Old Pap THOMAS.” The name was not over-respectful, perhaps; but it fitly expressed the love and fealty of the brave men who followed him from victory to victory. Our hardy volunteers, while as obedient to discipline as they were steady in fight, when off duty and around the camp-fires, retained their democratic habits and their sturdy personal independence of thought and language. They picked off the shoulder-straps and dissected the uniforms, and looked down below the commission and into the man, and measured his real worth and work with unerring instinct. The judgments they formed of their leaders, expressed in quaint and familiar epithets, have undoubtedly anticipated the graver verdict of the historian.

___________________

A good quick biography of General Thomas from the National Park Service mentions that during the Mexican-American War Thomas became good friends with his superior Braxton Bragg, the future commander of the Confederate forces during the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga. In antebellum days Bragg would recommend Thomas for a teaching position at West Point (where he met his wife, Frances Lucretia Kellogg) and as a “major in the newly created 2nd United States Cavalry” out in California. Robert E. Lee was West Point superintendent while Thomas taught there and became Lieutenant Colonel of the Second Cavalry. The Park Service piece also mentions the agonizing decision Thomas had to make as the Civil War broke out – whether to stay loyal to the Union or go with his home state. Whereas Robert E. Lee went with Virginia, George Thomas was disowned by his family because he stayed true to the Union.

And it wasn’t just his family that knew about his decision. George H. Thomas was Number 8 on a list of Virginians considered traitors to their State. From the Richmond Daily Dispatch September 11. 1861:

Notes of the war.

The Enquirer publishes the following 11st [list?] of Virginia Officer[s] in Lincoln’s Army:

1. Brevet Lieutenant General Winfield Scott.

2. Colonel P. St. George Cooke, Second Cavalry.

3. Lieutenant-Colonel Washington Sea well, Eighth Infantry.

4. Lieutenant-Colonel Edward J. Steptor, Ninth Infantry.

5. Lieutenant-Colonel James D. Graham, Engineers.

6. Major Campbell Graham, Engineers.

7. Major Lawrence P. Graham, Second Dragoons.

8. Major George H. Thomas, Second Cavalry.

9. Major N. C. MeRae, Third Infantry.

10. Major T. L. Alexander, Eighth Infantry.

11. Major Albert J. Smith, Paymaster.

12. Major Benj. W. Bryce, Paymaster.

13. Major G. D. Ramsey, Ordnance.

14. Major T. S. S. Laidly, Ordnance.

15. Major F. N. Page, Assistant Adjutant General:

16. Major John F. Lee, Judge Advocate General.

17. Major William Hayes, Second Artillery.

18. Major William H. Gordon, Third Infantry.

19. Major George C. Waggaman, Assistant Quartermaster General.

20. Captain John Newton, Engineers.

21. Capt. J. W. Davidson, First Dragoons.

22. Capt. W. J. Newton, Second Dragoons.

23. Capt. T. G. Williams, First Infantry.

24. Capt. T. A. Washington, First Infantry.

25. Capt. G. Chapin, Seventh Infantry.

26. Capt. L. H. Marshall, Tenth Infantry.

27. Capt. Jesse L. Reno, Ordnance.

28. Capt. E, W. B. Newby, First Cavalry.

Several in the above list have been rewarded by Lincoln with promotion. Two of them, Majors George H. Thomas and Lawrence P. Graham, have been made Brigadier-Generals. Col. Cooke, who has been for some time in Utah, it was supposed, would retire from the Yankee service, and link his destiny with his native land for weal or woe. Possibly he may yet do so. The friends of Col. Steptoe have asserted with confidence that he, too, would be true to his State and to his name, and we are still unwilling to place his name on the list of Scott traitors. Before the commencement of our present troubles, in consequence of ill health, he obtained a furlough with a view to a somewhat protracted absence from the country. He returned from Europe, however, some weeks since, and was in Montreal the last we heard of him.

A couple months later (November 13) the Richmond Daily Dispatch reported the Virginia and/or Confederacy was taking action against the traitors. I don’t understand how it worked out but the government was trying to take property of alien enemies or those associated with the enemies:

Sequestration proceedings.

–Since our last report, proceedings have been instituted in the Confederate States District Court against the following persons, to sequester property of alien enemies:

… Camilla Loyal — David G. Farragut, alien enemy. … Thos. W. Thomas — George H. Thomas, alien enemy Bolling W. Haxall–Mrs. Maria Scott, (wife of Gen. Winfield Scott,) alien enemy. …

_______________

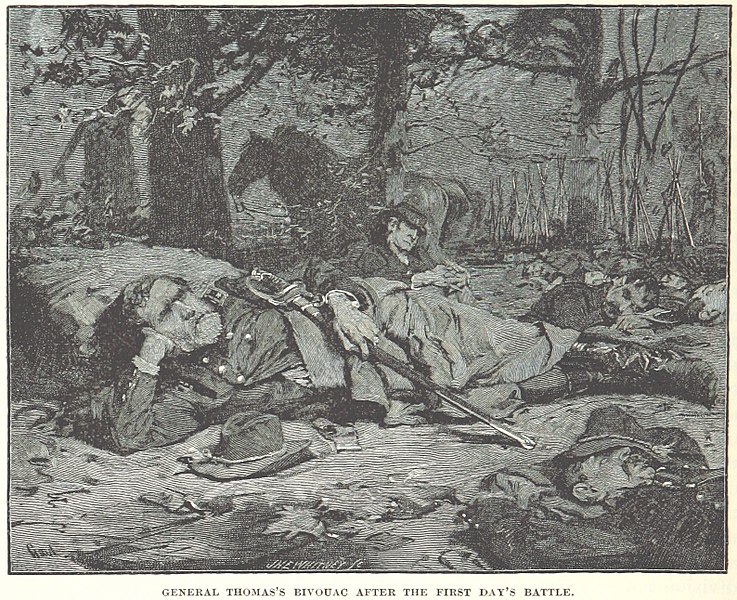

In its October 10, 1863 issue (at Son of the South) Harper’s Weekly covered the Battle of Chickamauga and included some reporting by the Herald’s Mr. W. F. G. Shank, who described General Thomas’s grim composure while his men were holding off the rebel onslaught at the close the second day:

Just behind Harker’s brigade, posted in the key of the position, there was a slight hollow in a large open field, in which were still standing about a dozen dead trees. In this deflection of the field, at the time the last fight of Sunday began, there were gathered together Generals Thomas, Gordon Granger, Garfield, Wood, Brannan, Steadman, Whittaker, and Colonel Harker. As the fight opened, Harker and Wood ran up the hill to their brigade and division, both being the one and the same. Steadman, Brannan, and Whittaker, rode off to join their commands. Garfield continued to indite his dispatch. Granger and Thomas remained, the latter on his horse, his arms folded, listening to the awful fire that soon raged along the line with the coolness of assured victory or the calmness of despair. His lips were compressed. His eyes glanced from right to left as the shell and canister exploded about the field, and once I saw him, just as the fight opened, most furiously glance up at a large, beautiful white pigeon or dove which alighted upon a dead tree above him and watched the battle from her dangerous nest. The representative man of that line, in unfaltering courage (Thomas), may be also said to have represented by his thoughts at that moment the thoughts of all. Watching him, we could see his anxiety at the reflection that if that line did not stand all would be lost; and each and every man there knew that the safety of themselves, but more the safety of the whole army, depended upon them. To be defeated there was to be cut to pieces or captured. To be routed was to fall back upon Chattanooga in disgrace, to be ignominiously taken in flight. There was no help to be expected save in the darkness of the slowly approaching night.

Happily Thomas’s men did hold out till night, and the army was saved.

_______________

About 15 months after Chickamauga the Union army under General Thomas thoroughly destroyed the Army of the Tennessee commanded by John Bell Hood at the Battle of Nashville. Before the battle General Thomas’s superiors were worried that Hood would give him the slip and have clear marching all the way to the Ohio River. Generals Halleck and Grant ordered Thomas to attack immediately. General Thomas explained that he wanted to refit his cavalry first and then he had to wait for a sheet of ice to melt before he could successfully attack. Here’s a description from Was General Thomas Slow at Nashville? at Project Gutenberg (pages 30-35):

THE PANIC AT WASHINGTON.

In spite of the plainest statements of the situation, of the great disparity of forces, of the dictates of prudence to remain on the defensive until he could strike an effective blow, which he expected to deliver in a few days, Thomas was prodded and nagged from City Point and Washington as no officer in command of an army had been before, and treated day by day as if he needed tutelage. In the last dispatch of the series of clear explanations,—which under other circumstances than the seething of that inside panic which a full appreciation of the complications that Sherman’s march to the sea had caused would doubtless have been accepted,—General Thomas was peremptorily ordered to “attack Hood at once without waiting for a remount of your cavalry. There is great danger in delay resulting in a campaign back to the Ohio.” This was sent in reply to a telegram of Thomas showing that there was the greatest activity in getting the cavalry ready, and he hoped to have it remounted “in three days from this time.” To this Thomas replied that he would make all dispositions and attack according to orders, adding, “though I believe it will be hazardous with the small force of cavalry now at my service.” Orders to prepare for attack were immediately sent out, and dispositions for the attack began. Meantime a sleet storm came on which covered the country with a glaze of ice over which neither horses, men, nor artillery could move even on level ground, to say nothing of assaulting an enemy intrenched on the hills. The same day Halleck telegraphed: “If you wait till General Wilson mounts all his cavalry you will wait till doomsday, for the waste equals the supply.” And General Grant telegraphed orders relieving Thomas. The latter telegraphed Halleck that he was conscious of having done everything possible to prepare the troops to attack, and if he was removed he would submit without a murmur.

The order of relief was suspended. The sleet storm continued. All of General Thomas’s officers agreed that it was impracticable to attack. Some of them even found it impossible to ride to headquarters because of the ice, and in the midst of it came an order from Grant: “I am in hopes of receiving a dispatch from you to-day announcing you have moved. Delay no longer for weather or reinforcements.”

Thomas replied:

“I will obey the order as promptly as possible, however much I regret it, as the attack will have to be made under every disadvantage. The whole country is covered with a perfect sheet of ice and sleet, and it is with difficulty the troops are able to move about on level ground.”

To Halleck, Thomas replied:

“I have the troops ready to make the attack on the enemy as soon as the sleet which now covers the ground has melted sufficiently to enable the men to march, as the whole country is now covered with a sheet of ice so hard and slippery that it is utterly impossible for troops to ascend the slopes, or even move upon level ground in anything like order. Under these circumstances I believe an attack at this time would only result in a useless sacrifice of life.”

The reply to this, unquestionably born of the panic to which allusion has been made, was an order sending General Logan to relieve Thomas. Grant himself then started from City Point for Nashville to assume general command. But the ice having melted, he was met at Washington by the news of Thomas’s victory.

The delay that Thomas had insisted upon, in the face of orders twice given for his relief, gave him the cavalry force he required for the decisive blow he intended to strike.

While the official inside at City Point and Washington bordered on panic, everything at Nashville was being pressed forward with activity and vigilance, and at the same time with deliberation, prudence, and the utmost imperturbability. At length, and at the first moment possible consistent with a reasonable expectation of success, the attack began. …

__________________________________

Henry V. Boynton is credited with being the author of Was General Thomas Slow at Nashville?, but in his Preface he points out that much of the material was first published as an article in the New York Sun of August 9, 1896. At any rate, the Union cavalry was very important (pages 36-39):

“The developments of the battle, the energy and success of the pursuit, and the marvelous results of the whole, namely, the virtual destruction of a veteran army, reveal at every step what General Thomas had in mind when he insisted upon waiting till he could remount his cavalry.

“In no other battle of the war did cavalry play such a prominent part as in that of Nashville. In no other pursuit did it so distinguish itself. …

“Many officers have organized and built up an effective cavalry force in times of rest and peace, but no one except General Wilson ever did it in the heat and hurry of a desperate midwinter campaign. And he could not have succeeded, nor could any man have accomplished it, in the face of the interferences which were attempted, but for the protection and support of the peerless and imperturbable Thomas.”

As it turned out Philip St. George Cooke did stay true to the Union, unlike a couple family members: “The issue of secession deeply divided Cooke’s family. Cooke himself remained loyal to the Union, but his son, John Rogers Cooke, became an infantry brigade commander in the Army of Northern Virginia. J.E.B. Stuart, the famous Confederate cavalry commander, was Cooke’s son-in-law. Cooke and Stuart never spoke again, Stuart saying, ‘He will regret it only once, and that will be continually.'”

The Herald’s reporter William Franklin Gore Shanks wrote 1866’s Personal Recollections of Distinguished Generals. He remembered General Thomas and included this snippet from Chickamauga (see Project Gutenberg pages 63-65):

This methodical and systematic feature of his character found an admirable illustration in an incident to which I was a witness during the battle of Chickamauga. After the rout of the principal part of the corps of McCook and Crittenden, Thomas was left to fight the entire rebel army with a single corps of less than twenty thousand men. The enemy, desirous of capturing this force, moved in heavy columns on both its flanks. His artillery opened upon Thomas’s troops from front and both flanks; but still they held their ground until Steedman, of Granger’s corps, reached them with re-enforcements. I was sitting on my horse near General Thomas when General Steedman came up and saluted him.

“I am very glad to see you, general,” said Thomas in welcoming him. General Steedman made some inquiries as to how the battle was going, when General Thomas, in a vexed manner, replied,

“The damned scoundrels are fighting without any system.”

Steedman thereupon suggested that he should pay the enemy back in his own coin. Thomas followed his suggestion. As soon as Granger came up with the rest of his corps, he assumed the offensive; and while Bragg continued to move on his flanks, he pushed forward against the rebel centre, so scattering it by a vigorous blow that, fearful of having his army severed in two, the rebel abandoned his flank movement in order to restore his centre. This delayed the resumption of the battle until nearly sunset, and Thomas was enabled to hold his position until nightfall covered the retirement to Rossville Gap.

Thomas is not easily ruffled. It is difficult alike to provoke his anger or enlist his enthusiasm. He is by no means blind to the gallantry of his men, and never fails to notice and appreciate their deeds, but they never win from him any other than the coldest words in the coldest, but, at the same time, kindest of commendatory tones. He grows really enthusiastic over nothing, though occasionally his anger may be aroused. When it is, his rage is terrible. …

You can read all of Harper’s Weekly for 1870, including pages 253 and 257, at the Internet Archive.

I found “Thomas’s Bivouac at Chickamauga” at Wikimedia. AgnosticPreachersKid’s 2009 photo of the west side of the Thomas equestrian statue in Washington D.C. is licensed under Creative Commons. Hal Jespersen’s map of the last part of Chickamauga is also licensed under Creative Commons. You can find the map of Battle of Nashville at Wikimedia The non-stereo image of the general in profile was published in Was General Thomas Slow at Nashville? now at Project Gutenberg.

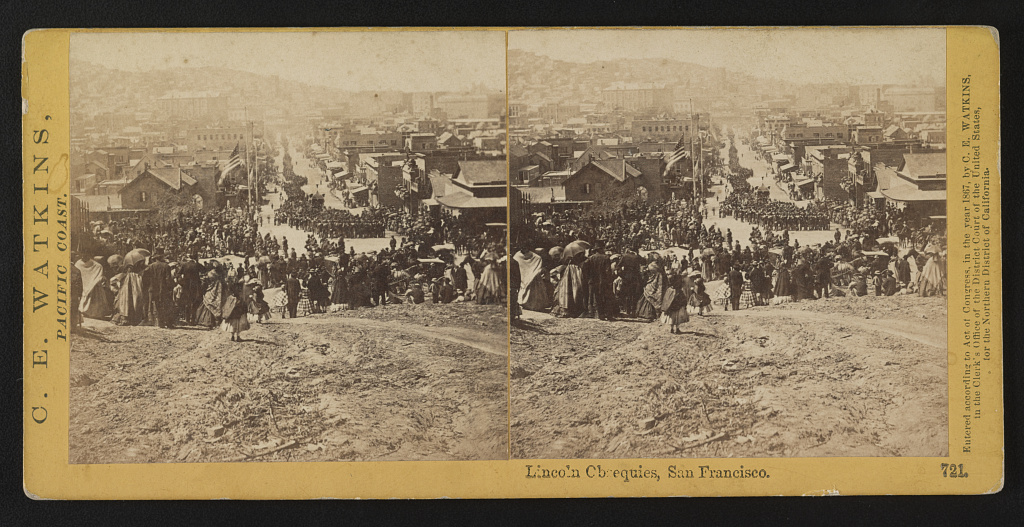

From the Library of Congress: Alfred R. Waud’s drawing of Confederate troops advancing at Chickamauga; from Russain Hill; the Presidio circa 1856; the portrait of Stewart Lyndon Woodford circa 1870; Thomas portrait in stereo; Halleck; “Grant and staff at City Point, summer 1864″;Federal outer line; Nashville depot; Thomas war flag; survivor – “C.S.A. Veterans, Sgt. J.J. Dackett, Co. I. 3rd S.C.V., wearing hat with bullet holes received in the Battle of Chickamauga Sept. 20, 1863”; Carol M. Highsmith’s 2017 photograph of the Georgia Monument at Chickamauga military park; San Francisco paying its respects

_________________

More April Funerals

When I was looking for pictures of San Francisco I found the stereograph above. Five years before General Thomas’s death the people of San Francisco paid their respects for the slain Abraham Lincoln, even though his actual funeral took place in Washington, D.C. According to the April 19, 2019 issue of The Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY, page A2), that was a pretty common occurrence across the country. The article begins with a comparison – Even given today’s uncertainties over the corona virus pandemic, it’s hard to imagine the manic week Americans endured beginning April 9, 1865, from Lee’s surrender on Sunday to the assassination of President Lincoln on Friday night and his death on Saturday morning. “Here in Syracuse, like many other cities around the country, the profound national grief took the cathartic form of a mock funeral for the martyred President, a sad tribute indeed.” The mayor shut down schools, churches, and businesses on April 19th for a citywide procession; cannon fired, church bells rang. The eulogist praised Lincoln and the end of slavery. “He is gone, but he has left us the rich inheritance of a redeemed and regenerate and free country.”

________________