Recently I posted an excerpt from the October 18, 1860 issue of The New-York Times. about the Minute Men in South Carolina. In the same issue The Times published more Southern reaction to the big Republican victories in the state elections of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. The reaction varied, but there was definitely talk of disunion. I think it would have been reasonable to wonder if the American flag was going to lose some of its 33 stars.

The New-Orleans Picayune did not think Lincoln could be elected, but, if he were elected, it did not think the majority of Southerners would support secession. Lincoln’s election would be lawful. There was a hint that the Picayune thought the Southern states should secede if the Fugitive Slave act were repealed.

The Nashville Union said the threat of “Black Republicanism” should cause everyone in the South to put aside party differences and unite to protect their constitutional rights.

The Richmond newspaper used an economic and financial argument to warn about what would happen if Lincoln became president.

From The New-York Times. October 18, 1860:

The Richmond Examiner seizes the occasion to urge the claims of BRECKINRIDGE and LANE.

Then commenting on the pecuniary pressure in the South,

and charging it upon the prospect which there is of

the Federal Government changing hands, it says:

“If a financial pressure of continuous and general

character follows the election of LINCOLN, the days of

this Union are not only numbered, but they will be

very few. With a fall in the price of cotton and negroes,

there will come popular discontent, and against

the Government which has produced the convulsion

that discontent will be directed. In the South, the

capitalists who now dread disunion and convulsion

most, who are always opposed to disturbance, will be

the first to cry for war or separation. The Northern

man will have to whistle for his debt. Civil commotion or

war is always a stay law, and often an extinguisher

of the debt, without the payment of money.

Such a motive is a low and a bad one, but it is operative

in all revolutions, and it is not to be forgotten

when men are seriously calculating the probable results

of political or social acts. We say to the capitalists

in both sections, if you wish to enjoy your capital

—to the laborer, if you wish to get wages—to the

tradesman, if you wish to make profit—do you prevent

the election of LINCOLN; and we sincerely believe that

this can now be done, if at all, only by voting for

BRECKINRIDGE and LANE.”

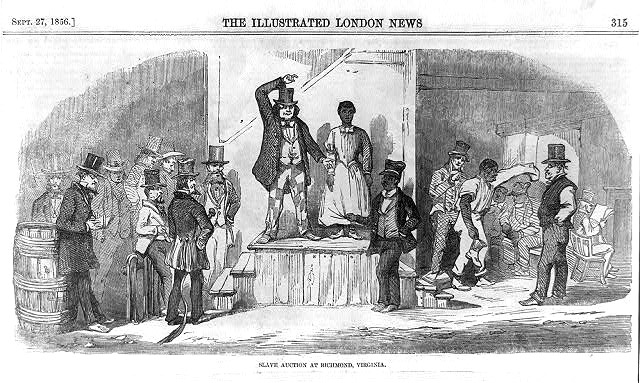

Reading this editorial from the Richmond newspaper that equates cotton and black people as commodities immediately reminded me of my trip to Fort Sumter in 1996. I was enjoying walking around Charleston. Then I remember walking by what apparently was the Old Slave Mart. Seeing an actual slave market made a bad part of our history a bit more real – not just something to read from a book. The Richmond editorial’s concern about the price of slaves affected me in a similar way.

Apparently, however, it is not that uncommon to analyze the prices of cotton and slaves in the pre-Civil War South. Yesterday afternoon I had a serendipitous experience. I worked on this post for awhile before going to the dollar-a-bag used book sale at our local library. At the sale I opened up a big green book to a chart that compared the price of cotton and slaves from 1802-1860! What a coincidence!

The book turns out to be what I take to be a high school textbook from 1990: The American Nation, A History of the United States by John A. Garraty and Robert A. McCaughey. The book covers a lot about the economics of slavery. The main idea is that as the demand for cotton rose and the efficiency of (slave) labor rose because of the cotton gin, the demand for and price of slaves skyrocketed. The chart I mentioned shows that while the price of cotton remained fairly steady during the first part of the 19th century, the price of a “Prime Field Hand” tripled from $600 in 1802 to about $1800 in 1865. Elsewhere the authors note that the slave price reflected the increase in value of southern agricultural output. They calculate the “crop value per slave” – it rose from $15 in the early part of century to more than $125 in 1859.

I was startled when I read the line about the price of “cotton and negroes”; however, given the importance of cotton to the South’s economy, I can see why those calculations were being made. It is like calculating labor costs nowadays – except that nowadays the wages go to the laborer.

As always I’d like to hear what you think.

Great Sites

I’ve been getting some excellent public domain photos from Shmoop

The picture of the slave auction is from Learn NC