Talk about “Yankees.” It is time we were all Yankees, if by the term is meant a shrewd, energetic and indomitable encounter with difficulties. Tell us about being “Abolitionists!” We are all Abolitionists by force of events — by the stern logic of war.

150 years ago today New-Yorkers could read all about terrible conditions in the recently vanquished South – and in tenements in their own fair city. Here’s an editorial from Georgia that urged it’s readers to accept the facts that the South had lost the war and that it’s slaves were freed. Georgians needed to get to the practical work of managing the huge task of replacing the plantation system with free labor.

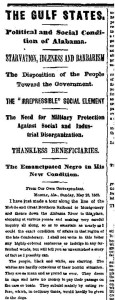

From The New-York Times June 12, 1865:

THE NEGRO IN GEORGIA.; The Great Problem Before the South– How Shall Society Accommodate Itself to the New Order of Things? THE GREAT PROBLEM FOR THE SOUTH. WHAT SHALL BE DONE WITH THE EMANCIPATED SLAVES? A SYSTEM OF PLANTATION LABOR.

The following extracts from the Macon Telegraph give an interesting view of the present condition of the negroes in the South, and of the general feeling of the white population on the subject of free labor:

From the Macon Telegraph, May 30.

The programme of the Telegraph under reconstituted Federal authority, is very plain and simple. It is to accept whatever is inevitable, and make the best of it. Show us what we have got to do, and we will do it to the best of our ability, and with what grace and heartiness we may. If there is any other course consistent with interest, wisdom and duty, we fail to discover it.

Nevertheless, there seems to be, upon the part of some few of our readers, an indisposition or inability to comprehend even so plain a thing as the attitude we occupy. They address us with arguments and complaints, particularly about what we have written on the subject of negro emancipation, as if they held us responsible for a fact, the existence of which we only recognize. In the name of justice, Mr. Caviler, what have we to do with the practical fact of the abolition of slavery in Georgia or elsewhere? Did we decree it? Do we ask for or order it? Does our judgment approve of it as a piece of abstract policy? Not a whit more than you or yours. As a matter of opinion, we hold it an ill-advised policy, both as to the negro, his master, and the substantial interests of the country at large.

Why, then, reproach us, and argue the case as though we were in favor of impoverishing this or that class, or destroying this or that interest? We are in favor of no such thing. We may recognize the troubles, losses and vexations which will grow out of this business just as fully as you do, and the only difference between us is that you propose to mope and groan over them, while we are in favor of bestirring ourselves to devise and apply all the mitigating and remedial agencies the case admits of. You give us long homilies about the constitutionl impossibility of immediate emancipation, and in so doing are simply trying to practice a delusion upon yourselves, which we are unwilling to try upon the public. We tell you slavery is already gone, Constitution or no Constitution. The death sentence has already been pronounced, and final execution is only a question of a few days or hours; while, under such circumstances, we hold a respite as undesirable.

Now what ought to be done in this state of the case? The government can turn the negro loose, and it can set on foot some general system of hiring, by way of substitute; but it cannot master the subject in all its complicated details. The petticoated, patriarchal and absolute systems of Austria or Russia would be practically powerless to manage the infinite details of such a work. Our government may begin it, but the people of the United States will soon turn away in disgust from such business. Our system is totally unsuited to it. The theory of democratic republicanism is non-intervention with trade, labor and domestic economy. Smelling and tasting committees are the exceptions, and not the rule. It keeps out of the kitchen and the meal-tub as a matter of taste, as well as principle; and however for a time a contrary practice seems to have prevailed, it is but an episode in the political drama, an escapade in the national history, which will be cut short and abandoned before long. The Government of the United States will trouble itself particularly about negroes, as a class, no great while longer. It will wash its hands of them, and with good soap at that.

Hence, we say, the States have got to take up this business, and, in Georgia, this great and knotty question stares us in the face — how are we going to prevent half a million emancipated negroes from being vagrants and public burdens, lounging about in towns and neighborhoods, and spreading moral and physical disease among the people? How are we going to make them, instead, useful members of society — good laborers — comfortable, well-fed and happy, as they were before the emancipation? To look at the question in its private as well as public aspect, how are you, Mr. Planter, to prosecute your labors with freedmen instead of slaves — maintain discipline and efficiency, neighborhood order and security, suppress vagrancy around you — protect property, secure the comfort and well-being of your laborers, and enforce justice and order among themselves? Now these are the great questions we should be thinking and talking over; and depend upon it we have got to solve them ourselves, and upon their solution hangs the question of beggary or comfort, prosperity or ruin for the State of Georgia, and for yourselves and ourselves. Talk about “Yankees.” It is time we were all Yankees, if by the term is meant a shrewd, energetic and indomitable encounter with difficulties. Tell us about being “Abolitionists!” We are all Abolitionists by force of events — by the stern logic of war.

From the Same.

Within the past few days we have had several reports from the country of the most discouraging character, so far as many of the planters are concerned. A large proportion of these, located along the railroad lines, have been deserted by their field hands, leaving none behind except the very old and helpless young. Their crops are in the ground, the small grains repening for the harvest, and the corn and cotton suffering for seasonable culture. But, owing to the absence of the customary work hands, everything is at a standstill; there is no laboring force sufficiently strong to either gather the ripening or cultivate the growing one. The prospect is a gloomy one, both for the masters and the helpless ones left behind, and earnest inquiries are made by the humane as to how apprehended and apparently inevitable suffering can be averted.

Some few masters are disposing of the helpless, who would be too heavy a tax upon them, by removing them from their plantations. Deprived of the labor to produce supplies, by the absence of the negro men belonging to the destitute families, the latter are disposed of in some way, so as to get rid of the incumbrance. Numbers have been sent to this city, where, it is patent to all, they must suffer and die — where there is neither employment nor food for them, and there is a population already overtaxing the means of support within their reach.

The great question now is, how shall the unfortunates be saved from suffering at present, and their future provided for, until such time as definite regulations are established for the government of the planters and negroes. The old masters cannot, in many instances, provide for their old dependents — the government cannot do it now, and certainly will not do it in future. Both the government and the planters would fail in ability, unless assisted by the labor of the able-bodied negro. What, then, is to be done at once?

It is useless to talk to the negro who has left his home. He took his departure therefrom, entertaining the most exalted ideas of the blessings and privileges that would attach to him when a freedman. These he has not realized, it is true — he has yet experienced nothing but want and privations. But he is hopeful; thinks “there is a better day coming,” and is yet unconvinced of his error. Sambo will have to suffer more before he realizes the extent of his mistake, or his dreams prove illusions.

The supplies furnished the negro and his family can be charged to him in the meantime. The details necessary to carry out some such arrangement will readily suggest themselves to every one, and we need not remark further than to say the plan is embraced in the single idea that remuneration for labor will hereafter be necessary, and to provide against impending difficulties, the policy of the Government had, perhaps, better be anticipated at once.

Wikipedia summarizes Reconstruction in Georgia:

At the end of the American Civil War, the devastation and disruption in the state of Georgia were dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The state’s chief cash crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. The state government subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war.