After their victory at Chattanooga Federal troops pursued the retreating rebels into Georgia. 150 years ago today the “Sallust” correspondent of the Richmond Daily Dispatch telegraphed home a description of the situation. It was published last in a series of telegrams from the front.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch December 1, 1863:

Latest from General Bragg.

[from our Own Correspondent.]

Dalton, Ga., Nov.27th, 1863.

–The army reached Ringgold last night without molestation until near the town, when our rear was attacked. …

[Third Dispatch.]

Resaca, Nov.29.

–The enemy retired to Ringgold after their bloody defeat by Gen. Cleburne, who captured 300 prisoners, four flags, and killed and wounded 1,500.

Their advance is now at Ringgold, and our advance is near them. They destroyed the bridge when they retreated.

The Confederate army is in position at Dalton and in front of it. All the trains are ordered back to Resaca, (ten miles in rear of Dalton.)

The enemy cannot advance without the railroad, and they have no cars. There is no reason to apprehend an advance now, if at all, this winter.

The rains are heavy, and the roads horrible.

It is bitter cold, and shoes and blankets are needed for our suffering soldiers.

Sallust.

The next day Sallust expanded on the telegram and pondered whether Union General Grant would try to advance further toward Atlanta during the coming winter. The correspondent believed the odds were against it because of the difficulty of repairing railroads and/or foraging and crossing rivers during winter. The cold weather is already affecting the Confederate army short of blankets and shoes lost on the retreat.

From the Richmond Daily Dispatch December 7, 1863:

From Gen. Bragg’s army.

[from our Own Correspondent.]

Resaca, Ga., Nov.30, 1863.

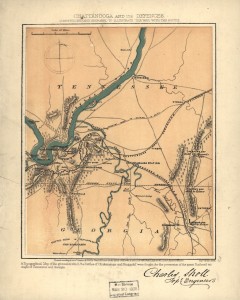

The news from the front, a telegraphic synopsis of what I sent you last night, is of an encouraging and reassuring character. The enemy’s advance forces, after their bloody repulse between Tunnel Hill and Ringgold by Cleburne, retreated to the mountain pass at the latter place, where they still remained at last advices. They destroyed the bridges as they retired, thus showing that they do not propose to follow us further at present, and that they are not willing for the Confederates to get at them. Our rear is on this side of the burnt bridges beyond Tunnel Hill, where it presents a stern and defiant front. The main army is encamped around Dalton, where General Bragg has established his headquarters. The trains and such forces as had reached Resaca have been ordered back to the same place, and I shall follow as soon as my horse is in condition to travel.

The opinion was advanced in my telegram last night that there was no reason to apprehend an immediate advance of the Federal army. Such is still my conviction. If the army could not be subsisted at Chattanooga without the aid of the railroad from that point to Bridgeport, neither can it be subsisted at Dalton or Kingston without the possession of the Western and Atlantic road, and a sufficient number of locomotives and cars for the transportation of supplies. These locomotives and cars Gen. Grant has not and probably cannot procure for some time. Rolling stock which would answer for one road would be inadequate for two. The Federal commander will find it necessary, therefore, in order to an advance into the country, to accumulate supplies at Chattanooga, to repair the railway bridges which his advance forces have already destroyed in the vicinity of Ringgold, and such others as the Confederates may destroy, and to provide a sufficient number of care and engine to transport supplies for his troops.

In advancing this opinion, I take it for granted that he must advance, if at all this winter, by the railroad route, and not by Willis Valley, in the direction of Rome. The roads by the latter route, if not impassable in winter to heavily laden army wagons, are of such a character as to render it difficult, if not impossible, to subsist as large an army as his by wagon trains alone. Indeed, if Gen. Grant had intended to move directly upon Rome, Stevenson, and not Chattanooga, would have been chosen as his base of supplies, and, in that event, the struggle for Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge would not have been necessary.

But will Gen. Grant advance at all this winter? [It] is impossible, of course, for any one except the Federal commander himself to answer this interrogatory, though it is permissible for us to speculate upon his probable designs, with the aid of such lights as are furnished by his previous conduct and present situation. Omitting, as unnecessary to the argument, any inferences that might be drawn from his former campaigns, it is sufficient to say that he has neither the supplies nor the transportation to enable him at this time to move upon Atlanta, the acknowledged goal of his ambition and the desires of his Government. To advance along the railroad at this inauspicious season of the year, and repair the road as he moves, would be a herculean task — a task, let us hope, far beyond his power of accomplishment. It is one hundred and thirty-eight miles from Chattanooga to Atlanta; the wagon made are inferior, and the intervening country is traversed by several and numberless water courses.

Can he cross this wide track under the heavy rains and frequent snows of winter? If he cannot, will he tempt to march a part of the way now, and the remainder in the spring? The suggestion was made some time ago, in one of these letters, that his efforts this fall would probably be limited to an attempt to get possession of the region of country lying west of the west branch of the Chickamauga, and that early next spring he would put his army in motion towards the great railway centre at the Confederacy. Can he do more than this now? The district from this place to Chattanooga, fifty miles in width, has been stript of its supplies, and an invading army would have to bring along with it all it required for its support. Grant may make an effort, however, to get possession of Dalton, the point where the Georgia and East Tennessee road unites with the Western and Atlantic road, and even to reach the Etowah river; but there is no reason to believe that he will attempt to go further now. The immediate possession of Dalton was doubtless one of the objects of his pursuit of Gen. Bragg since it would have cut off all communication by railway with Knoxville, and all possibility of succor to Gen. Longstreet.

That an effort will be made to capture Long street and his command, there is no room to doubt. At last accounts, the 23d inst., Knoxville was completely invested by the Confederates, who were only waiting for reinforcements, then about due, to make an assault upon the town. An intelligent officer, who left on that day, is very confident that the attack, if not prevented by the success of the enemy at Chattanooga, would prove successful.–Wheeler, with a portion of his command, has arrived at Dalton, having on his way chased the enemy from Cleveland and recaptured a portion of our lest wagon train.

Capt. Hoback, of the Quartermaster’s department, informs me that our total loss of wagons during the late battle, and the operations which preceded and succeeded it, was about one hundred, including ten ordnance wagons taken on Missionary Ridge. Our loss of artillery is not known to me, but I suppose it was about equal to our captures at Chickamauga — say forty guns. I will endeavor to send you a detailed account of our losses in this particular as soon as I return to D[a]lton.

The weather is exceedingly cold, and many of the troops lost their blankets and shoes in the resent fight and on the retreat. Will not the people open their hearts and purses?

Sallust.

The following cartoon was published in the December 12, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly (at Son of the South. Maybe it means that the North had come to realize that Chattanooga was a big victory but far from conclusive.

![[Battle of Ringgold, Ga.] (by Alfred R. Waud, 1863 November 27; LOC: LC-DIG-ppmsca- 21308)](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/21308r-300x173.jpg)