In 1870 Charles Sumner introduced a Civil Rights bill in the United States Senate. While on his deathbed in March 1874, Senator Sumner implored his onlookers to make sure the Civil Rights bill did not fail. That plea might have taken on a greater urgency after the 1874 midterm elections in which Democrats took control of the House of Representatives. Republicans would probably need to get the bill passed before the last session of the 43rd Congress ended in March 1875. In its “Domestic Intelligence” section, the December 26, 1874 issue of Harper’s Weekly noted that the House Judiciary Committee discussed the Civil Rights bill on December 8th. A subcommittee was appointed to draft a new bill. One member of the subcommittee, Alexander White, a Republican from Alabama, proposed a bill that would ensure that in many public businesses and in public education black people would have “separate accommodations, but equal in convenience,” so that there would be equal privileges but no association between blacks and whites. Apparently a bill was reported that only applied the separate but equal concept to public education. Harper’s Weekly excoriated separate but equal public education in its January 9, 1875 issue:

AN ACT TO CONFIRM PREJUDICE.

THE probability of the passage of a civil rights bill is not great, but that is no reason for the introduction of such an act as has been presented to the House by the Judiciary Committee. If, as the opponents of the bill constantly declare, we cannot abolish prejudice by law, we are certainly not called upon to sustain and perpetuate it by law. Yet this is what the proposed bill does. It is an act to stigmatize a class of American citizens on account of color and previous condition of servitude. This it does by authorizing any State to maintain separate schools or institutions with equal facilities in all respects to all classes entitled thereto. But as separate schools are demanded only on account of color, this is the authority to establish them. Of course such a provision makes the whole bill ridiculous, as any shrewd Democrat could instantly show by moving to amend by making the provision which applies to schools apply also to “inns, public conveyances on land and water, theatres, and other places of public amusement.” If the prejudice against color is to be respected in the school-house, why not in the theatre and the tavern and the railroad car? It is no harder for a white child to sit beside a colored child at school than for a white parent to sit beside a colored parent in a car or at a public table or in a theatre. The distinction is without a difference. The bill as reported is an insult to every intelligent colored citizen, as it is a humiliation to every white citizen who remembers that the Constitution guarantees to all the equal protection of the laws — a guarantee which is deliberately violated when the law stigmatizes any class of innocent citizens under any pretense whatever.

The folly of such a rule was shown by Mr. CONWAY’S letter describing his experience as Superintendent of Schools in Louisiana, and by the daily reports from New Orleans, which state that “the color line in schools promises to be the momentous question, as it is difficult to settle who are colored.” As for the alleged prejudice, it is now frankly confessed that before the war the lighter-colored children — quadroons and others — were admitted to the schools, and no issue was raised; while it is perfectly well known that some of the most refined, cultivated, courteous, and wealthy citizens in that city were “tainted” with color. But not only is it impracticable to decide who is “colored,” but even if every child who is to be stigmatized by this law were coal-black, so that no question could arise, the mischief lies in the obloquy thus cast by law upon certain citizens to whom the Constitution secures equality. Suppose any other class against whom there is a similar feeling should be selected for this leper-like segregation, its enormity and injustice would be at once conceded. If, for instance, the Jews were by law separated from the rest of their fellow-citizens in schools and other public institutions, the sense of shame in all decent American breasts would soon burn out the law from the statute-book. In darker ages and more barbarous countries than ours the Jews were the victims of an inhuman prejudice. What does the honorable American think of those times and countries? And does he wish that his country to-day shall follow that example? There is, indeed, a difference in the cases. The feeling against the Jew was the growth of a Christian tradition of hatred against those who had crucified the Son of God. The feeling against the colored race is the American tradition of hatred against those whom we have foully wronged.

The prejudice unquestionably exists, but why should a Republican Congress propose to strengthen and perpetuate it by law? Is any member of Congress so amusingly stupid as to suppose that a prejudice strong enough to separate the schools would permit them to be equal “in all respects?” or that it is of any practical use to enact that a pariah who is excluded from the schools and cemeteries may have “full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land and water, theatres, and other places of public amusement?” Moreover, it is as impossible to determine what is a full and equal enjoyment of such privileges as it is to decide who is “colored.” The bill will not pass, and it certainly ought not to pass.

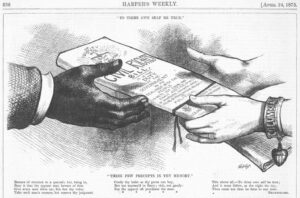

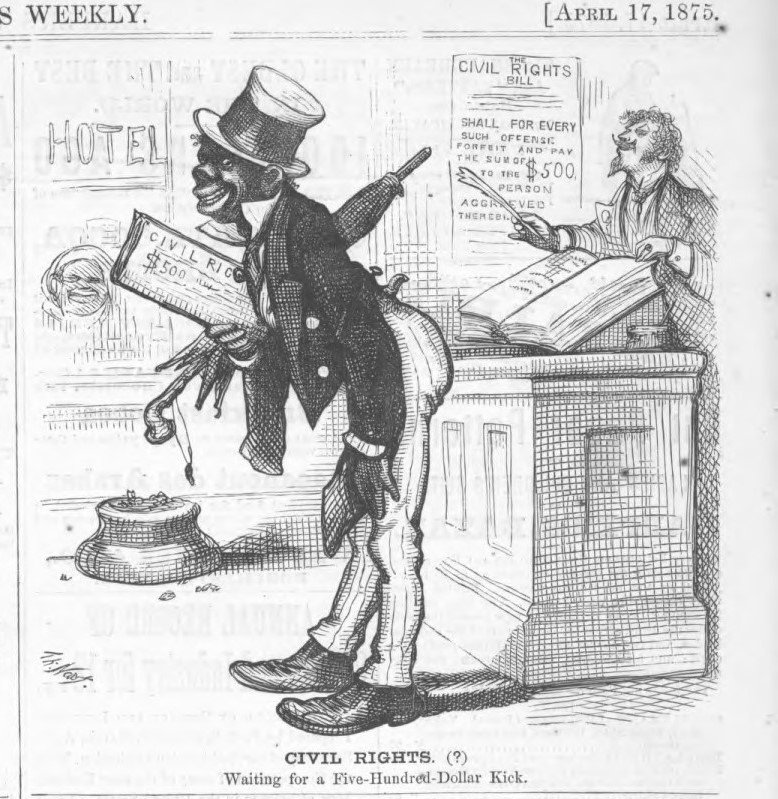

Actually, a bill did pass. President Grant signed the Civil Rights Act of 1875 on March 1st, but that law did not mention public education: “… all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement …” Those who did not provide the equal accommodations could be held liable in civil or criminal court. The civil penalty was $500. Federal courts had jurisdiction. The act did not mention anything about “separate but equal.”

In its March 2, 1875 issue Richmond’s Daily Dispatch called the act an abortion. The law was not what the negroes wanted, and whites saw the law as “an attempt to insult the superior race and stir up strife.” Harper’s Weekly criticized the act for excluding public education. It published some cartoons and a letter by Congressman Benjamin Butler, who maintained the act only covered rights that blacks should already have had under common law. In July

The Supreme Court agreed with that last point. According to the Federal Judicial Center, “In The Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that the act was unconstitutional because the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to state, and not to private, action.”