– Reconstruction in Alabama

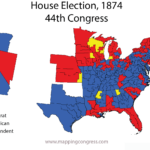

Overall, the 1874 United States elections were a boon to the Democratic Party, especially in the House of Representatives where Republicans lost 92 seats and the Democrats gained a dominant majority: “The Panic of 1873, a series of scandals, and an unpopular Congressional pay raise all damaged the Republican Party’s brand. With the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, the importance of the parties’ roles in the Civil War also receded in the minds of many. Though Republicans won governorships in Northern states such as Pennsylvania, the election increased Democratic power in the South, which it later dominated after the end of Reconstruction.”

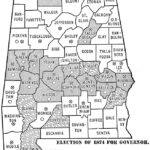

Democrats did gain power in Alabama. Although there wasn’t an election for U.S. senator, the Democrats picked up four House seats and the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, George S. Houston, defeated David P. Lewis, the Republican incumbent. Historian Eric Foner has written that Alabama was the second black belt state (after Georgia) to be “redeemed” – after the 1874 election white Democrats dominated state politics well into the 20th century. Although the economic depression was a factor, Alabama Democrats made race the main issue of the 1874 campaign. For example, “Democrats harped particularly on the school integration clause of the pending [federal] Civil Rights Bill …” That bill divided black and white Republicans – the Republican convention nominated all whites for state offices, refused to endorse the Civil Rights Bill, and emphasized that the party did not support racial social equality or mixing the races in schools and accommodations. Democrats used violence and destruction to hinder the Republican campaign and reduce black turnout. The Election Massacre of 1874 disrupted black voting in the Barbour County towns of Eufaula and Spring Hill. Armed whites also prevented blacks from voting in Mobile. Black turnout was high, but the violence helped Democrats win in Barbour and six other black-majority counties. “With Democrats in control of the state offices and both houses of the General Assembly, Reconstruction in Alabama had come to an end.” [1]

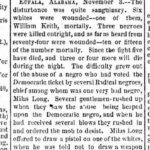

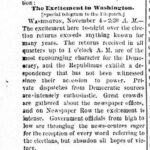

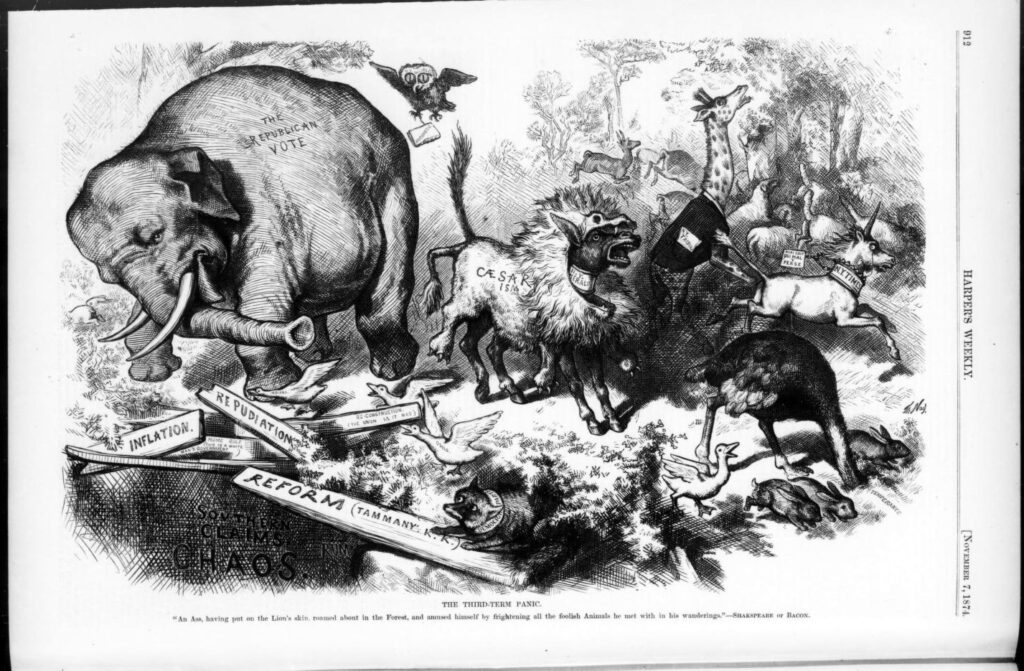

The telegraph was working well 150 years ago. The day after the election Richmond’s Daily Dispatch knew the Democrats had a good election overall. It’s a little hard to make out, but the paper headlined “A Glorious Day for the Conservatives and Democrats,” “Glad Tidings From All Points of the Compass,” “Serious Riot in Alabama,” “Massachusetts Redeemed and Beast Butler Bottled,” etc. The front page had some reports from Eufaula. The next day the editors declared the election “The Popular Revolution” and thought the vote indicated support for the “superior race.” The editors also thought the election results would discourage General Grant from seeking a third presidential term, but he might just try anyway for the good of the country – “Caesarism” was one of the many issues in 1874. In its November 21, 1874 issue, Harper’s Weekly said President Grant should have made it clear that he wasn’t going to run again.

Walter L. Fleming agreed with Eric Foner that the 1874 election ended Reconstruction in Alabama. In his 1905 Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama he includes the 1874 election in a chapter called “The Overthrow of Reconstruction.” There were many factors involved in the campaign, but Democrats did make race the leading issue. Here is Fleming’s account of the election itself:

The Election of 1874

The election of 1874 passed off with less violence than was expected; in fact, it was quieter than any previous campaign. The Democrats were assured of success and had no desire to lose the fruits of victory on account of riots and disorder. So the responsible people strained every nerve to preserve the peace. A regiment of soldiers was scattered throughout the Black Belt and showed a disposition to neglect the affairs of the blacks. But here, in the counties where the numerous arrests had been made, the blacks voted in full strength. In fact, with few exceptions, both parties voted in full strength, and, as regards the counting of the votes, it was the fairest election since the negroes began to vote. There were instances in white counties of negroes being forced to vote for the Democrats, while in the Black Belt negro Democrats were mobbed and driven from the polls. But the negro Democrats resorted to expedients to get in their tickets. In one county where the Democratic tickets were smooth at the top and the negro tickets perforated, the Democrats prepared perforated tickets for negro Democrats which went unquestioned. In other places special tickets were printed for the use of negro Democrats with the picture of General Grant or of Spencer on them and these passed the hurried Radical inspection and were cast for the Democrats. In Marengo County the Democrats purchased a Republican candidate, who agreed for $300 that he would not be elected. By his “sign of the button,” sent out among the negroes, the latter were instructed to vote a certain colored ticket which did not conform to law and hence was not counted. Other candidates agreed not to qualify after election, thus leaving the appointment to the governor.

In the Black Belt, now as before, the negroes were marshalled in regiments of 300 to 1500 under men who wrote orders purporting to be signed by General Grant, directing the negroes to vote for him. In Greene County 1400 uniformed negroes took possession of the polls, and excluded the few whites. A riot in Mobile was brought on by the close supervision over election affairs, which was objected to by a drunken negro who wanted to vote twice, and who declared that he wanted “to wade in blood up to his boot tops.” The negro was killed. A conflict at Belmont, where a negro was killed, and another at Gainesville were probably caused by the endeavor of the whites to exclude negroes who had been imported from Mississippi. By rioting the Republicans had everything to gain and the Democrats everything to lose, and while it is impossible in most cases to ascertain which party fired the first shot or struck the first blow, the evidence is clear that the desperate Radical whites encouraged the blacks to violent conduct in order to cause collisions between the races and thus secure Federal interference. In Eufaula occurred the most serious riot of the Reconstruction period that occurred in Alabama. The negroes came armed and threatening to the polls, which were held by a Republican sheriff and forty Republican deputies. Judge Keils, a carpet-bagger, had advised the blacks to come to Eufaula to vote: “You go to town; there are several troops of Yankees there; these damned Democrats won’t shoot a frog. You come armed and do as you please.” The Democrats were glad to have the troops, who were disgusted with the intimidation work of the previous month. Order was kept until a negro tried to vote the Democratic ticket and was discovered and mobbed by other blacks. The whites tried to protect him and some negro fired a shot. Then the riot began. The few whites were heavily armed and the negroes also. The deputies, it was said, lost their heads and fired indiscriminately. When the fight was over it was found that ten whites were wounded, and four negroes killed and sixty wounded. The Federal troops came leisurely in after it was over, and surrounded the polls. The course of the Federal troops in Eufaula was much as it was elsewhere. They camped some distance from the polls, and when their aid was demanded by the Republicans the captain either directly refused to interfere, or consulted his orders or his telegrams or his law dictionary. At last he offered to notify the white men wanted by the marshal to meet the latter and be arrested. Another commander, who took possession of the polls in Opelika in order to prevent a riot, was censured by General McDowell, the department commander. The troops were weary of such work, and their orders from General McDowell were very vague. After the election, as was to be expected, an outcry arose from the Radicals that the troops had in every case failed to do their duty.

When the votes were counted, it appeared that the Democrats had triumphed. Houston had 107,118 votes to 93,928 for Lewis. Two years before Herndon (Democrat) had received 81,371 votes to 89,868 for Lewis. The presidential campaign in 1872 had assisted Lewis. Grant ran far ahead of the Radical state ticket. The legislature of 1874-1875 was to be composed as follows: Senate, 13 Republicans (of whom 6 were negroes) and 20 Democrats; House, 40 Republicans (of whom 29 were negroes) and 60 Democrats.

The whites were exceedingly pleased with their victory, while the Republicans took defeat as something expected. There were, of course, the usual charges of outrage, Ku Kluxism, and the intimidation of the negro vote, but these were fewer than ever before. There was considerable complaint that the Federal troops had sided always with the whites in the election troubles. The Republican leaders knew, of course, that for their own time at least Alabama was to remain in the hands of the whites. The blacks were surprisingly indifferent after they discovered that there was to be no return to slavery, so much so that many whites feared that their indifference masked some deep-laid scheme against the victors.

The heart of the Black Belt still remained under the rule of the carpet-bagger and the black. The Democratic state executive Committee considered that enough had been gained for one election, so it ordered that no whites should contest on technical grounds alone the offices in those black counties. Other methods gradually gave the Black Belt to the whites. No Democrat would now go on the bond of a Republican official and numbers were unable to make bond; their offices thus becoming vacant, the governor appointed Democrats. Others sold out to the whites, or neglected to make bond, or made bonds which were later condemned by grand juries. This resulted in many offices going to the whites, though most of them were still in the hands of the Republicans.

Houston’s two terms were devoted to setting affairs in order. The administration was painfully economical. Not a cent was spent beyond what was absolutely necessary. Numerous superfluous offices were cut off at once and salaries reduced. The question of the public debt was settled. To prevent future interference by Federal authorities the time for state elections was changed from November, the time of the Federal elections, to August, and this separation is still in force. The whites now demanded a new constitution. Their objections to the constitution of 1868 were numerous: it was forced upon the whites, who had no voice in framing it; it “reminds us of unparalleled wrongs”; it had not secured good government; it was a patchwork unsuited to the needs of the state; it had wrecked the credit of the state by allowing the indorsement of private corporations; it provided for a costly administration, especially for a complicated and unworkable school system which had destroyed the schools; there was no power of expansion for the judiciary; and above all, it was not legally adopted.

The Republicans declared against a new constitution as meant to destroy the school system, provide imprisonment for debt, abolish exemption from taxation, disfranchise and otherwise degrade the blacks. By a vote of 77,763 to 59,928, a convention was ordered by the people, and to it were elected 80 Democrats, 12 Republicans, and 7 Independents. A new constitution was framed and adopted in 1875. …

You can also read about the Election Riots of 1874 at Encyclopedia of Alabama. The article explains that there was “evidence of the disparity in eyewitness accounts” about whether or not blacks voting in Eufaula were armed. To back that up, Eric Foner wrote that the blacks were unarmed; one of the reports from Eufaula said the blacks were armed.

George S. Houston started quite a trend. Alabamans only elected Democrats for governor from 1874 until Republican H. Guy Hunt won in 1986. There is an article at Wikipedia about the Solid South with lots of maps and charts (including gubernatorial elections).

Wikipedia cites Party of the People: a History of the Democrats pp.244-245 for the quote in the top paragraph in this post. LaDale Winling’s House election map is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. I haven’t made any changes. The map shows six Alabama districts; the state had two at-large districts. Six Democrats and two Republicans were elected.

Most of Harper’s Weekly for 1874 is at HathiTrust. I got the bottom picture on page 912 of the November 7, 1874 issue of Harper’s Weekly at Internet Archive. According to History that Thomas Nast cartoon was important for the adoption of the elephant as a symbol of the Republican party. The elephant was used for Republicans a couple times during the Civil War, “but the pachyderm didn’t start to take hold as a GOP symbol until Thomas Nast, who’s considered the father of the modern political cartoon, used it in an 1874 Harper’s Weekly cartoon.” “The Third-Term Panic” criticized Caesarism, and Nast returned to that theme and the elephant symbol for “Caught In A Trap” (above) in the November 21st issue. History says that Nast continued to use the symbol and by 1880 others were following along.

From the Library of Congress: Richmond’s Daily Dispatch – November 4 and November 5, 1874. The Alabama map and the pictures of Lewis and Houston are from the Fleming book.

- [1]Foner Eric, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. New York: HarperPerenial ModernClassics, 2014. Page 552-553. ↩