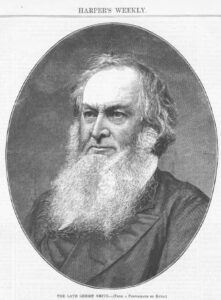

The well-known abolitionist Gerrit Smith died on December 28, 1874. Harper’s Weekly published a eulogy and brief biography in its January 16, 1875 issue:

GERRIT SMITH.

THE active antislavery movement in this country began forty years ago, and it is not surprising that many of its most famous champions have already gone or are departing in a ripe and honorable age. GERRIT SMITH was one of that band of moral heroes, and he was also one of the few Americans who may be called public men although not in official position, and who have a signal and influential individuality. He was born seventy-seven years ago, and his long life, his great riches, and his admirable talents were devoted to the relief and elevation of the forlorn and friendless and oppressed, and in a large and generous sense to the service of humanity. He was essentially a noble man. His advocacy of reforms was so strenuous and uncompromising that he seemed often fanatical and impracticable, but his great heart so overflowed with goodness and sympathy that no one who knew him could be his enemy, and in Congress, where nobody was more radical or more positive, no one was more heartily liked, even by his bitterest opponents.

In all things he was perfectly independent. No American had the courage of his opinions more than he, and he never hesitated to say what he thought with incisive vigor. There was always a man behind his words, and that, a wise man tells us, is the secret of eloquence. Naturally he was not a bigoted partisan. He was more political than the Garrisonian Abolitionists, with whom he most truly fraternized, and more radical than the Republicans, with whom he generally acted. His profound conviction that the long inhumanity with which the negro has been treated in this country has left in him and in public opinion consequences which are not to be removed by any merely formal provision led him to the deepest distrust of the Democratic party, under whose ascendency the crime against human nature in this country was defended and strengthened, and made him regard the possibility of a Democratic restoration as a deplorable calamity, for the reason that it was the restoration of the traditions, tendencies, and spirit of class oppression.

His charity was immense, and like EZRA CORNELL, he made himself the steward of his riches as a trust for the needy. Toward his home in Peterborough suffering men and humane causes constantly turned, and found his hospitable door and heart and purse always open. He knew no sectarian lines, and did not regard a man’s belief, but his life. A brave, good, beneficent man, who lived not for ease and selfish ambition, but for duty and the general welfare, he was, with the exception of one illness, robust in health as he was stalwart in frame. Indeed, his largeness and manliness of nature were well shown in his lofty form and bearing.

GERRIT SMITH was one of the men whose service to this country was not inferior to that of the fathers of the Revolution. As the earlier patriots made the nation independent, their later brethren made it free and just. When GERRIT SMITH began to take an interest in public affairs it was doubtful whether the American republic would not soon end in a huge slave empire. There was no national flag in Christendom so disgraced as ours, for no other was prostituted to an internal slave-hunting which was worthy of Dahomey. Mr. SMITH was one of those whose voice did not spare the infamy and its abettors, and who by their courageous eloquence and action aroused the dormant heart and conscience of America, until the people threw off the tyranny which was destroying them. For his part in this great service his name will be cherished and honored; and if those who know with him the perils that still menace our peace can not think without sorrow that the noble heart and lion port and uncompromising conscience of GERRIT SMITH have now become only a memory, they will not forget that they are also an inspiration.

GERRIT SMITH.

This distinguished philanthropist, whose sudden death in this city on the 28th ult. awakened universal sorrow and regret, was born at Utica, in this State, on the 6th of March, 1797. He was educated at Hamilton College, under President AZEL BACKUS, graduating in 1818 with the highest honors. During his collegiate career he gained a high reputation as an orator as well as a student. After leaving college he married the daughter of President Backus, but she died within less than a year. He subsequently married the daughter of Colonel FITZHUGH, of Maryland, who survives him.

His father was Judge PETER SMITH, a man of character and note in his day. In early life he was a partner in business with JOHN JACOB ASTOR. They had but little money, and kept a small shop in New York, where they dealt in furs. In summer they used to go up the Hudson to Albany on a sloop, and thence penetrate the interior of the State on foot, through forests, rivers, and swamps, to purchase the furs which the Indians had collected during the winter. These furs, with the assistance of the Indians, they would bring on their backs and in canoes to Albany, and thence transport them down the Hudson to New York. They continued several years in this business, accumulating a good deal of money, when they dissolved partnership. Mr. SMITH established his home in the interior of the State, and commenced buying lands on an extensive scale, until he counted his acres by hundreds of thousands. Years afterward, during the financial embarrassments of 1837, GERRIT SMITH applied to his father’s old partner for the loan of $250,000. It was granted without hesitation on his mere verbal promise to give mortgages on certain property. The mortgages were immediately executed, but, through the carelessness of the County Clerk, they were not forwarded, and several weeks afterward Mr. SMITH received a letter from Mr.Astor asking if he had forgotten to have them made out. All this time Mr. Astor had not held a scratch of the pen as security for this immense sum.

GERRIT SMITH was early placed in charge of his father’s business, and, while husbanding the original estate, gave his attention largely to land investments. His transactions were characterized by sagacity and foresight. He owned land at one time in fifty-six of the sixty counties in this State. In the northern part of New York he owned eight hundred thousand acres, all in one piece, known as “John Brown’s Tract.” Much of this immense tract was given away to negroes and other settlers, almost always with a little money to help them along.

Mr. SMITH had a fondness for legal studies, was well versed in the laws relating to real estate, and late in life applied for admission to the bar for the purpose of defending a poor friendless German accused of murder. He gained the case. From his youth he was a politician, though he held office but once in the course of his long life. In 1852 he was elected to Congress in the Madison and Oswego district, receiving a large majority over a popular candidate. He resigned his seat at the close of the first session. But though office-holding was not to his taste, he always took an active part in politics, acting first with the old Whig party and afterward with the Republicans. From his earliest youth he was a true friend to the oppressed and a stanch opponent of slavery. His home at Peterborough was the refuge of hundreds of fugitive slaves, whom he received, protected, and assisted in obtaining the means of living. He was, indeed, one of the most generous of men. No worthy applicant for relief was ever turned away empty-handed from his door. At his residence, which looked like the country-seat of an English nobleman, he exhibited an elegant and liberal hospitality.

During the war Mr. SMITH heartily supported the government in its efforts to suppress the rebellion, but he entertained no hostility toward the people of the South, and after the war joined with HORACE GREELEY in signing the bail bond of JEFFERSON DAVIS. He was at one time wrongfully accused of abetting JOHN BROWN’s wild scheme for revolutionizing the government by invading Virginia at the head of five white men and five negroes. Brown’s unhappy fate depressed him exceedingly, and for a little while so seriously affected his mind as to make a resort to the Utica Asylum a necessity. Under the treatment of Dr. GREY, he soon recovered fully.

At the time of his death Mr. SMITH was on a Christmas visit at the house of his nephew, General COCHRANE. He seemed to be in his usual health. On the morning of the 27th ult, he was stricken with apoplexy while dressing. He lingered until a little after noon the next day, when he passed away.

A 1957 history of New York State mentioned Gerrit Smith several times. The following is part of an overview of antebellum humanitarian reforms:

In this reform movement New York, particularly the upstate region, led the nation. No other section produced leaders of the caliber of Theodore Weld, Charles Finney, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Gerrit Smith, and the Tappan brothers in New York City. Probably the most irrepressible reformer was Gerrit Smith, whose career, like a seismograph, registered every tremor of the reform movement. Smith became interested as a young man in the benevolent societies, notably the Sunday School Union and the American Bible Society. Soon he branched out into temperance and abolition, the major concern of his adult life. But other reforms captured his fancy. He experimented with manual-training schools; he served as vice-president of the American Peace Society; he backed the crusade for women’s rights; he clamored against tobacco, secret societies, and British rule in Ireland.[1]

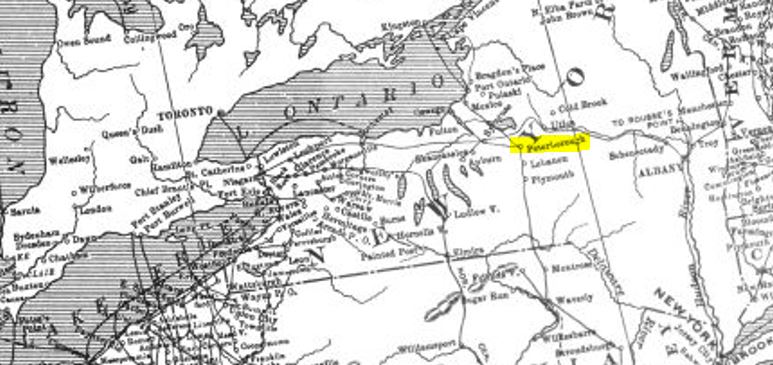

Smith is mentioned in The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom: A comprehensive history (at Project Gutenberg): “Gerrit Smith, the famous philanthropist, kept open house for fugitives in a fine old mansion at Peterboro, New York. He was one of the prime movers in the organization of the Liberty party at Arcade, New York, in 1840, and was its candidate for the presidency in 1848 and in 1852. He was elected to Congress in 1853 and served one term. It is said that during the decade 1850 to 1860 he ‘aided habitually in the escape of fugitive slaves and paid the legal expenses of persons accused of infractions of the Fugitive Slave Law.'” The quote is from O. B. Frothingham, Life of Gerrit Smith; National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. II, pp. 322, 323. I highlighted Peterborough in the map below. The map is from the Project Gutenberg book. The full map shows that the midwest had many more routes than central New York state.

According to Adirondack Almanack, the John Brown of John Brown’s tract is not the John Brown with the “wild scheme.” The Almanack only mentions 210,000 acres and nothing about Gerrit Smith. The National Park Service says, “As a philanthropist he gave away forty acres of Adirondack land in Northern New York to 3000 poor (and “temperate”) African Americans, to permit them to meet the requirements for voting, and in hopes of promoting self-sufficiency. He subsequently sold John Brown the land at North Elba, New York (where Brown is buried, near Lake Placid). The plan was for Brown’s family to help the new settlers to become productive farmers. Though much of the land was clearly unsuitable for farming, some lasting settlements were formed. In all it is estimated that Smith’s philanthropy reach $8 million before he died.”

According to New York History Net, Smith was implicated in John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry raid: “Though Smith and several of Brown’s other co-conspirators (The Secret Six) reportedly avoided knowledge of the specifics, there is little doubt that he was generally aware of, and helped to finance, Brown’s plans for anti-slavery action in Virginia.”

Gerrit Smith is a member of the National Abolition Hall of Fame at the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.

I got volume 19 of Harper’s Weekly (1875) from HathiTrust. The Gerrit Smith articles are on pages 50 and 52.

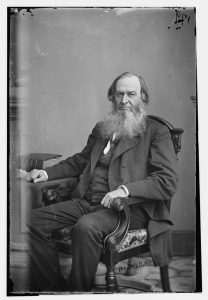

From the Library of Congress: the photo of Gerrit Smith

- [1]Ellis, David M., James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman. A Short History of New York State. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1957. Print. page 308.↩