According to Eric Foner in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, every election in Louisiana “between 1868 and 1876 was marked by rampant violence and pervasive fraud.” The results of the 1872 Louisiana gubernatorial election were highly disputed. Both carpetbagger Republican William P. Kellogg and Democrat John McEnery initially claimed victory. Eventually the federal government certified Kellogg as the winner of the election, but the Democrats were bitter about the situation. McEnery still believed he was the rightful governor. He organized his own militia, which in March 1873 attempted but was unable to take control of New Orleans police stations. During the Colfax Massacre in April 1873, “An estimated 62–153 Black militia men were murdered while surrendering to a mob of former Confederate soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan. Three White men also died during the confrontation.”

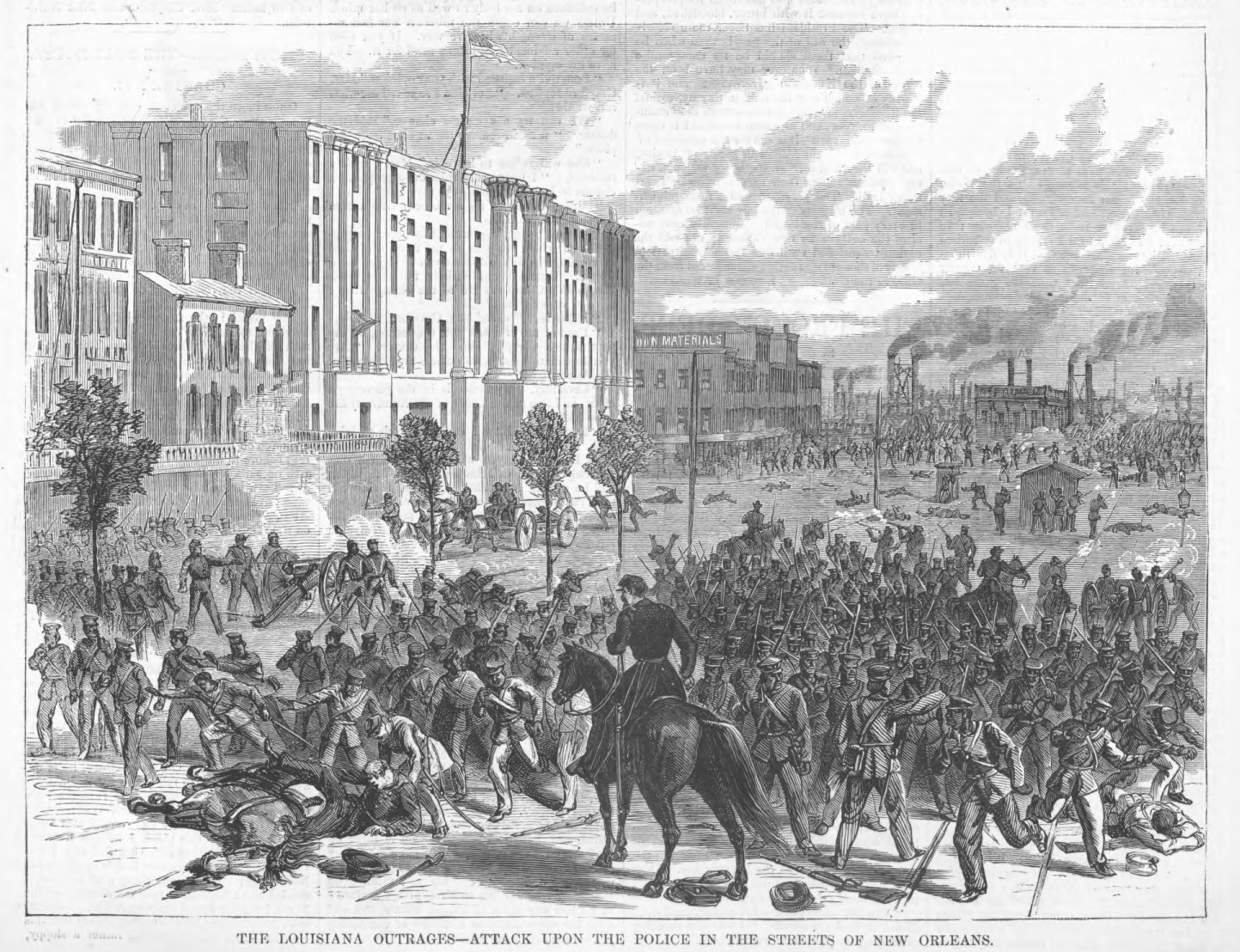

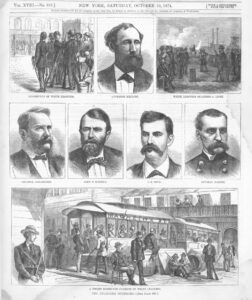

In 1874 the White League was formed. The League was “openly dedicated to the violent restoration of white supremacy. It targeted local Republican officeholders for assassination, disrupted court sessions, and drove black laborers from their homes.” In August the League killed six Republican officials in Red River Parish. The next month the White League started an insurrection in New Orleans with the goal of installing McEnery as governor. On September 14th, “3,500 leaguers, mostly Civil War veterans, overwhelmed an equal number of black militiamen and Metropolitan Police under the command of Confederate Gen. James Longstreet, and occupied the city hall, statehouse, and arsenal.” The insurrection ended when President Grant sent in more federal troops.

Harper’s Weekly provided some coverage about the Battle of Canal Street (or the Battle of Liberty Place) in each of its October 1874 issues. Here’s a summary of events from the October 3rd paper:

DOMESTIC INTELLIGENCE.

On September 14 a mass-meeting of the citizens of New Orleans was called to protest against the recent seizure of arms intended for the White League. A large concourse of men gathered in Canal Street, and adopted resolutions calling upon Governor Kellogg to “abdicate.” The Governor refused to accede to the demand. Mr. D.B. Penn, who had been Democratic candidate for Lieutenant-Governor at the last State election in Louisiana, then issued a proclamation, in which he charged Kellogg with having usurped the government, and called upon “the militia of the State, embracing all males between the ages of eighteen and forty-five years, without regard to color or previous condition, to arm and assemble under their respective officers for the purpose of driving the usurpers from power.” In response to this appeal crowds of armed men took possession of the city, erected barricades, defeated and dispersed the Metropolitan Police under General Longstreet, and compelled Governor Kellogg to seek the protection of the United States troops stationed at the Custom-house. Six or eight of the insurgent citizens and twenty or thirty of the police were killed during the fighting, and quite a large number were wounded on both sides. General Badger was severely wounded. Immediately on receiving official intelligence of this outrage, President Grant issued a proclamation, September 16, commanding the disturbers of the peace to disperse within five days. A concentration of United States troops at New Orleans was also ordered, under General Emory, commanding at that place. The firm attitude of the general government had its effect on the White Leaguers. They knew they had to deal with a man of stern resolution, and on the 18th, two days after the issue of the President’s proclamation, General Emory reported to Governor Kellogg the surrender of the insurgents and the re-establishment of order. There was no conflict between the insurgents and the United States troops.