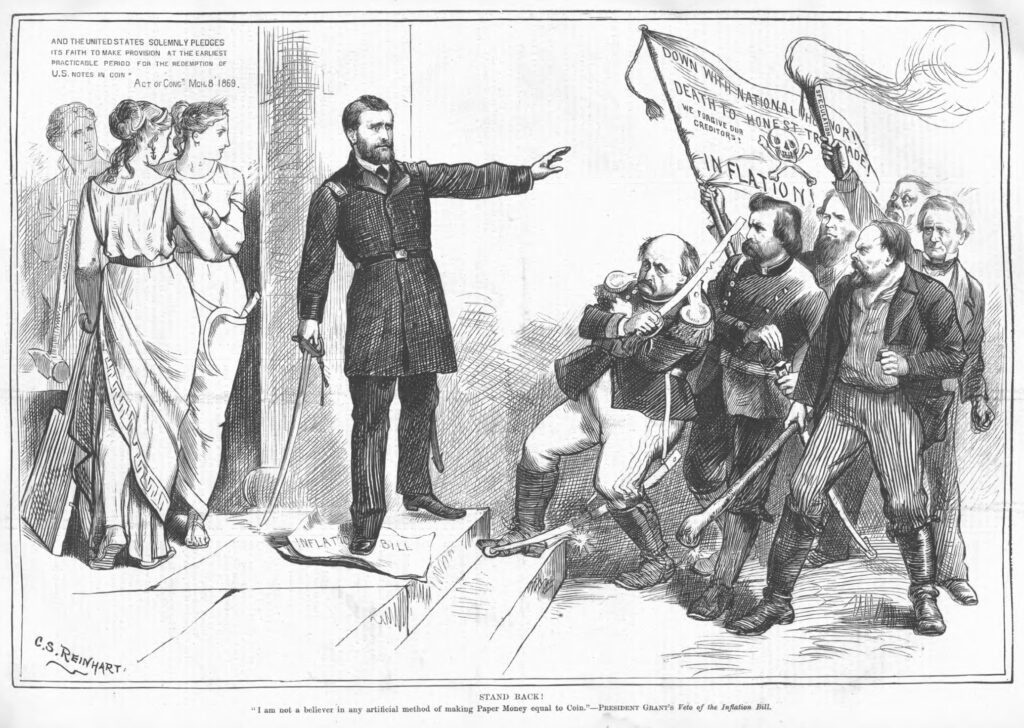

The Panic of 1873 led to a long-lasting depression in Europe and North America. In early 1874 Congress passed a bill that would expand the supply of paper currency not redeemable in gold. On April 22, 1874 President Ulysses. S. Grant vetoed the measure. In its May 9, 1874 issue Harper’s Weekly lauded the veto:

THE VETO.

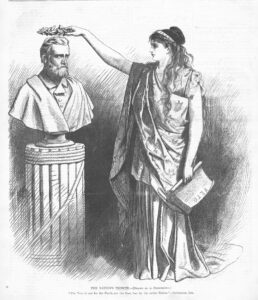

THE President’s veto of the inflation bill is the most important event of his administration. It saves the national honor, it redeems the pledge of the great popular majority which elected him, it renews the hope of the Republican party, and it restores the old regard of the country for the citizen whom it had so gladly honored for his great service in the field. The message has been every where considered and discussed. Every body has remarked its directness, cogency, and simplicity. It rests the objection to inflation upon the true ground. The bill sought inflation; inflation was a deliberate violation of the national faith solemnly pledged, and that faith must be maintained at all hazards. This is the clear statement of the message, and it comes from a President who has constantly urged speedy resumption. That the message was a surprise even to many of the President’s best friends is undeniable. His recent close association with many of the leading inflationists; his apparent impatience both with the New York and Boston delegations; the fact that he is a Western man, and that popular sentiment in that part of the country is represented to be strongly in favor of inflation; the fear of party results should he veto the bill — these and other considerations made his disapproval very doubtful.

The veto will have two kinds of results, political and commercial. The latter can be only good, for the reason that inflation would necessarily have destroyed confidence, and excited only a morbid and dangerous speculation. The rich man could take the risks of the game. The poor man was sure to suffer. The veto shows the President to be the friend of labor and of the producing class, whose interests are always served by financial confidence and steadiness. The political consequences are more obscure. Yet it is observable that while the inflationists have declared that expansion and irredeemable paper were the cause of the people, the great and warm expressions of public opinion, whether in public meetings, or in the press, or in the resolutions of boards and societies, and indeed in all the forms in which the feeling of a great country manifests itself, have been resolute and eloquent against inflation. The angry exclamations of some members of Congress upon the reception of the message were the natural expressions of the disappointment of warm advocates of a frustrated scheme. The debate in the Senate and the vote upon the veto are yet to come. It may show a feeling from which grave political consequences will follow. Doubtless it will be complicated with personal ambitions and rivalries, and hearty party co-operation between those who differ so radically upon so vital a point of public policy would seem to be impossible.

But the President has the happy consciousness that he is sustained by the deep conviction of the best men in his own party, by the sound and intelligent sentiment of the country, and by the recorded wisdom and experience of Christendom. At a dark and critical moment he has again served his country as few men in her history have had the opportunity to serve her. His action gives another glimpse of that quality in him which has drawn so many men toward him, and held them fast in spite of many discouragements and doubts. And if elsewhere in this paper we plainly criticise portions of his official conduct in which he seems to us to have failed, it is not with any doubt of the conviction that we have always expressed, that, whatever his failures, he is animated by a sincere and patriotic desire to do his duty.

There’s quite a bit of information out there about the Panic and resulting long depression, including from The New York Times and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The trigger for the Panic in the United States was on September 18, 1873 when the Jay Cooke & Co. bank suspended withdrawals for depositors at the bank’s New York City and Philadelphia houses. By the next day other financial firms failed. Although the government announced it would buy $10 million in bonds, on September 20th the New York Stock Exchange suspended trading for the first time in its history. The next day President Grant and Treasury Secretary William A. Richardson went to New York City to work out a solution. Many businessmen begged the president to do everything possible to increase the amount of currency in circulation. The government ended up buying $13 million in bonds.

Although the Panic subsided after about 40 days, the depression lasted for at least 5 years. The government tried to address the problem. In his December 1873 annual message to Congress, President Grant discussed the Panic in the section about the Treasury Department. I’m confused by the economics, but Grant did stress the importance of hard, metal-backed money:

“The revenues have materially fallen off for the first five months of the present fiscal year from what they were expected to produce, owing to the general panic now prevailing, which commenced about the middle of September last. The full effect of this disaster, if it should not prove a “blessing in disguise,” is yet to be demonstrated. In either event it is your duty to heed the lesson and to provide by wise and well-considered legislation, as far as it lies in your power, against its recurrence, and to take advantage of all benefits that may have accrued.

“My own judgment is that, however much individuals may have suffered, one long step has been taken toward specie payments; that we can never have permanent prosperity until a specie basis is reached; and that a specie basis can not be reached and maintained until our exports, exclusive of gold, pay for our imports, interest due abroad, and other specie obligations, or so nearly so as to leave an appreciable accumulation of the precious metals in the country from the products of our mines.

“The development of the mines of precious metals during the past year and the prospective development of them for years to come are gratifying in their results. Could but one-half of the gold extracted from the mines be retained at home, our advance toward specie payments would be rapid. …”

You can read President Grant’s veto message of the Inflation bill at The American Presidency Project. The president made it clear that he thought it was necessary to eventually return to hard money. For example, he quoted his own first annual message to Congress in December 1869: “Among the evils growing out of the rebellion, and not yet referred to, is that of an irredeemable currency. It is an evil which I hope will receive your most earnest attention. It is a duty, and one of the highest duties, of Government to secure to the citizen a medium of exchange of fixed, unvarying value. This implies a return to a specie basis, and no substitute for it can be devised. It should be commenced now and reached at the earliest practicable moment consistent with a fair regard to the interests of the debtor class. Immediate resumption, if practicable, would not be desirable. It would compel the debtor class to pay, beyond their contracts, the premium on gold at the date of their purchase, and would bring bankruptcy and ruin to thousands.”

President Grant’s veto was sustained. In 1875 Congress passed the Species Resumption Act, which required the government to “retire Greenbacks (currency not backed by gold) and committed the government to reinstate the gold standard in four years” (Liberty Street Economics). “By pegging the dollar against hard currency, the act helped curb inflation, tame speculation and produce a stable dollar. It turned the Republican Party toward a stance of conservative fiscal policies” (The NY Times article).