for a bête noire

There was a report 150 years ago last month that the ex-Vice President of the Confederacy admired the incumbent U.S. President, U.S. Grant. From the December 25, 1873 issue of The Valley Virginian (page 1):

Alexander H, Stephens does not indulge in the average Bourbon estimate of President Grant. Here is what he said, in conversation with a friend, a few days ago, concerning this bete noir of Democracy: “When I first met him in 1866, I made up my mind that Grant was one of the most remarkable men of the age. I said so, and wrote to that effect, before Grant was even thought of for the Presidency, and every year since has strengthened my conviction. He has shown a wonderfully clear conception of his duties nod powers as President. He has executed the laws as he has found them and is as little inclined to usurp power as any President we ever had; in this respect he is a great contrast to Jackson, who had an imperious will. Even in the Louisiana troubles he has illustrated his character. He enforced the decrees of the United States court, and when asked to send another Judge to New Orleans in place of Judge Durell, he replied that he could not interfere with the assignment of judges made by the Supreme court. Not much Caesarism in that.”

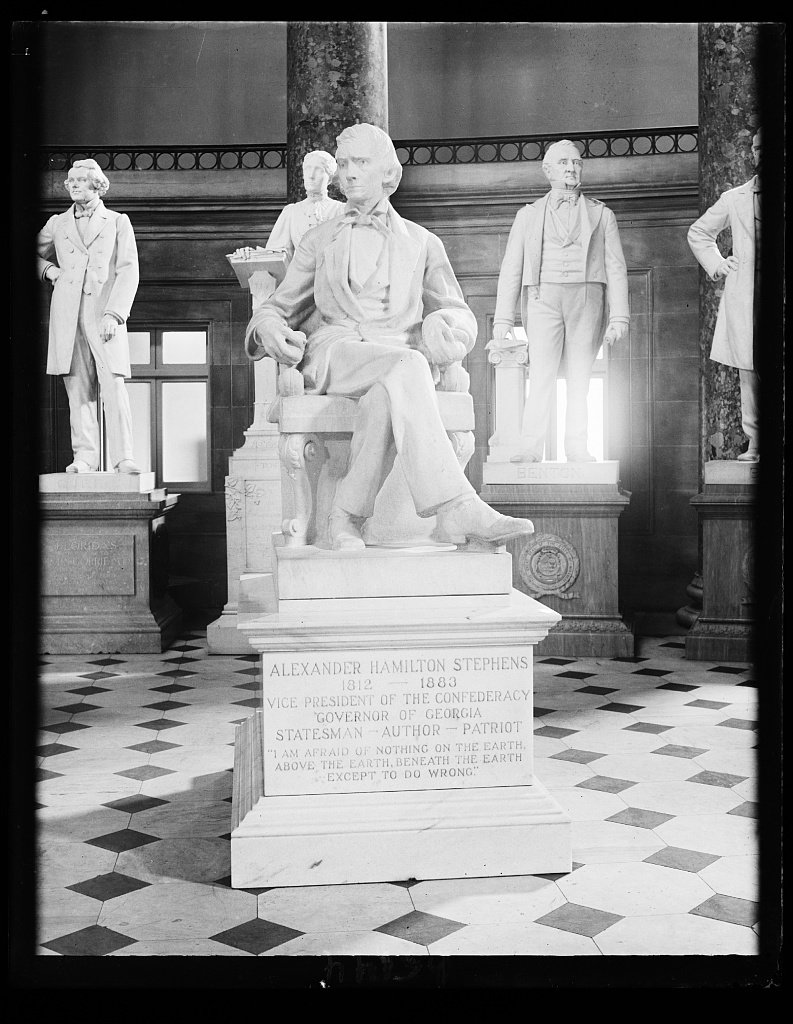

Before the war Mr. Stephens represented a Georgia district in the U. S. House of Representatives. On December 1, 1873 he returned to the U.S. Capitol as a representative from Georgia. From the December 20, 1873 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

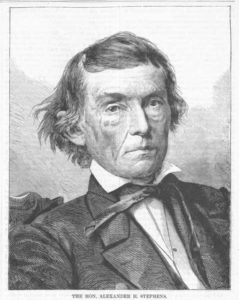

ALEXANDER H. STEPHENS.

THAT was a very striking scene in the House of Representatives when ALEXANDER. H. STEPHENS, of Georgia, appeared and took his seat. The ex-Vice-President of the Southern Confederacy entered the hall on crutches. He looked feeble and emaciated, but no more so than for several years past. Few of the members recognized him, and of all those in the hall there were probably not more than five or six who were his contemporaries during any part of the fourteen years when he sat in the House, from 1843 to 1857. By a proper and graceful courtesy, Mr. DAWES, as the senior member of the House, and Mr. STEPHENS, on account of his age and infirmities, were allowed the privilege of the first choice of seats; the others had to abide the chance of the lottery. Mr. STEPHENS selected a prominent seat in front of the Speaker’s desk.

During the swearing in of members Mr. STEPHENS stood leaning on one crutch, supported on the other side by Mr. P. M. B. YOUNG, ex-major general of the Confederate army. “Baring his white head,” says a spectator of the scene, “and lifting his thin, ghostly hand, his eyes seemed to burn with a strange light as they were fastened on the Speaker.” He is the first really conspicuous Southern statesman of the period before the war who has returned to the national legislature. What memories must have crowded upon his mind while he stood there to take the oath! He had striven earnestly to prevent secession and avert war. With impassioned eloquence he had warned the people of the South against the folly into which they were rushing with blind and headlong haste, and pictured in glowing colors the greatness and growth of the nation, which, he said, was “the admiration of the civilized world,” and represented “the brightest hopes of mankind.” Drawn into the secession movement against his better judgment and against his choice, he was distinguished by the bold candor with which he avowed the principles on which the new government was to be founded. He denounced as fundamentally wrong the idea of the equality of the races. “Our new government,” he declared, in his well-known speech at Savannah in March, 1861, “is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas. Its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world based upon this great philosophical and moral truth.” This frank avowal had even more effect at the North than at the South, and served to quicken and strengthen the spirit of patriotism which saved the Union. Not the least strange of the circumstances under which Mr. STEPHENS takes his seat in Congress is the presence of several representatives of the very race whose subordination to the whites he so forcibly affirmed.

Mr. STEPHENS was born in Taliaferro County on the 11th of February, 1812, and is consequently nearly sixty-six years old at the present time. A newspaper correspondent writing from Washington says of him: “Mr. STEPHENS is afflicted with rheumatism of the severest type, which has thrown one hip out of place, and though he can hobble about a room with the aid of a cane, he has to use crutches on the street. Physically he is very feeble, but his intellect is as clear as ever. He eats animal food very seldom, and then sparingly. He is fearfully emaciated, and so colorless that his slender fingers seem almost transparent.”