It was becoming a tradition. 150 years ago, for the tenth year in a row, the United States president proclaimed a national day of Thanksgiving for a Thursday at the end of November.

THANKSGIVING DAY 1872

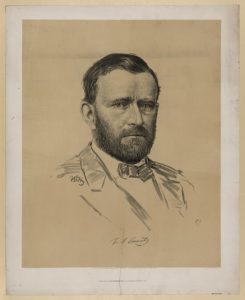

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA – A PROCLAMATION

Whereas the revolution of another year has again brought the time when it is usual to look back upon the past and publicly to thank the Almighty for His mercies and His blessings; and Whereas if any one people has more occasion than another for such thankfulness it is the citizens of the United States, whose Government is their creature, subject to their behests; who have reserved to themselves ample civil and religious freedom and equality before the law; who during the last twelvemonth have enjoyed exemption from any grievous or general calamity, and to whom prosperity in agriculture, manufactures, and commerce has been vouchsafed;

Now, therefore, by these considerations, I recommend that on Thursday, the 28th day of

November next, the people meet in their respective places of worship and there make their

acknowledgments to God for His kindness and bounty.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 11th day of October, A.D. 1872, and of the Independence of the United States of America the ninety-seventh.

U.S. GRANT

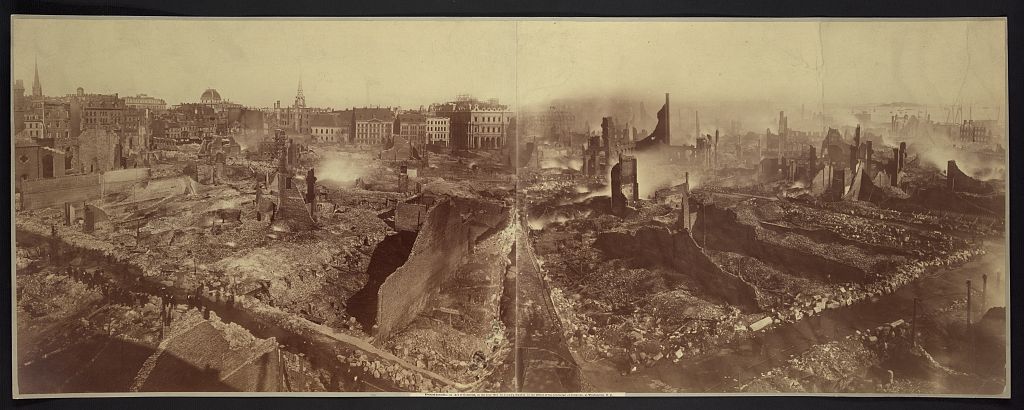

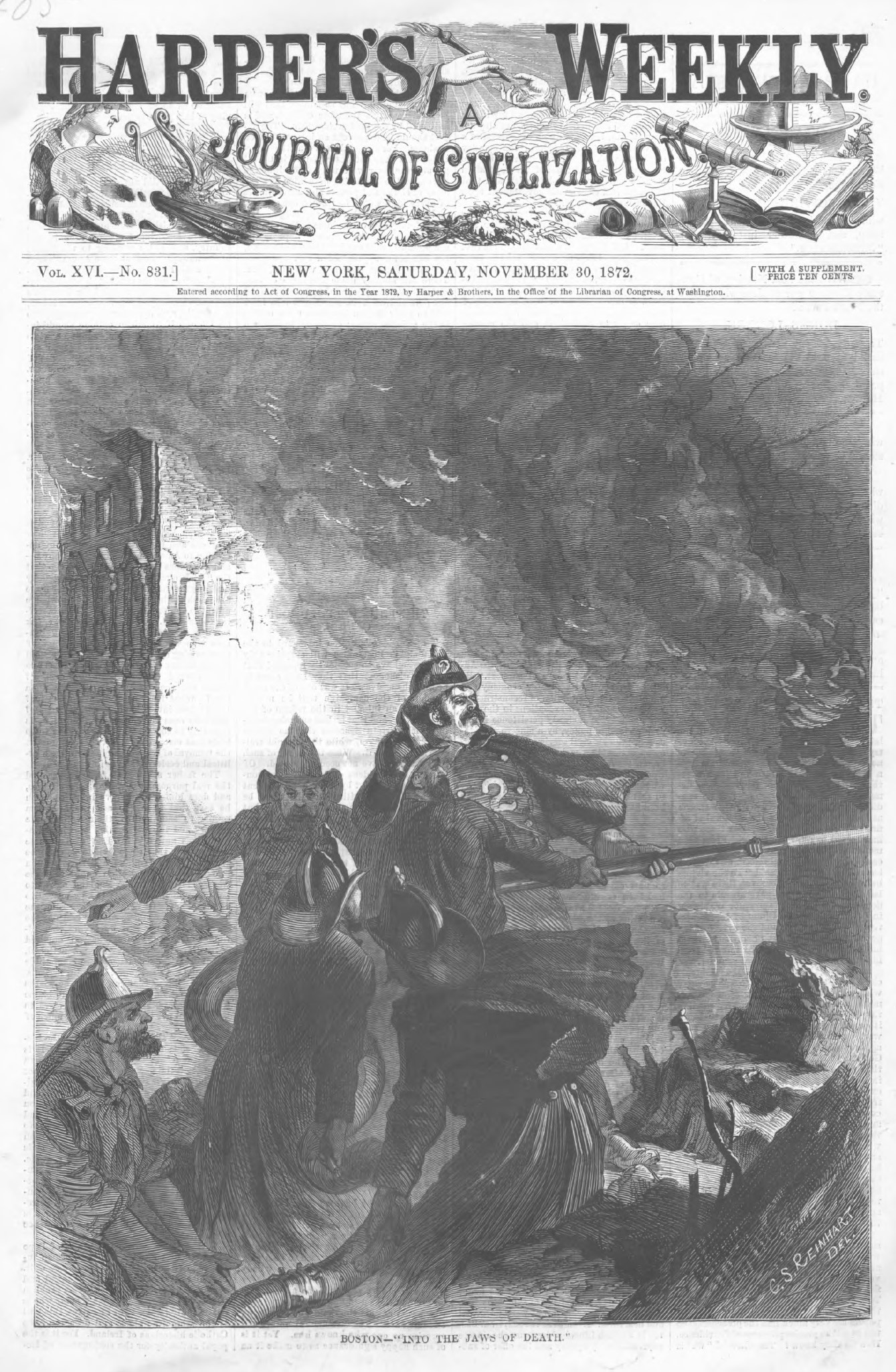

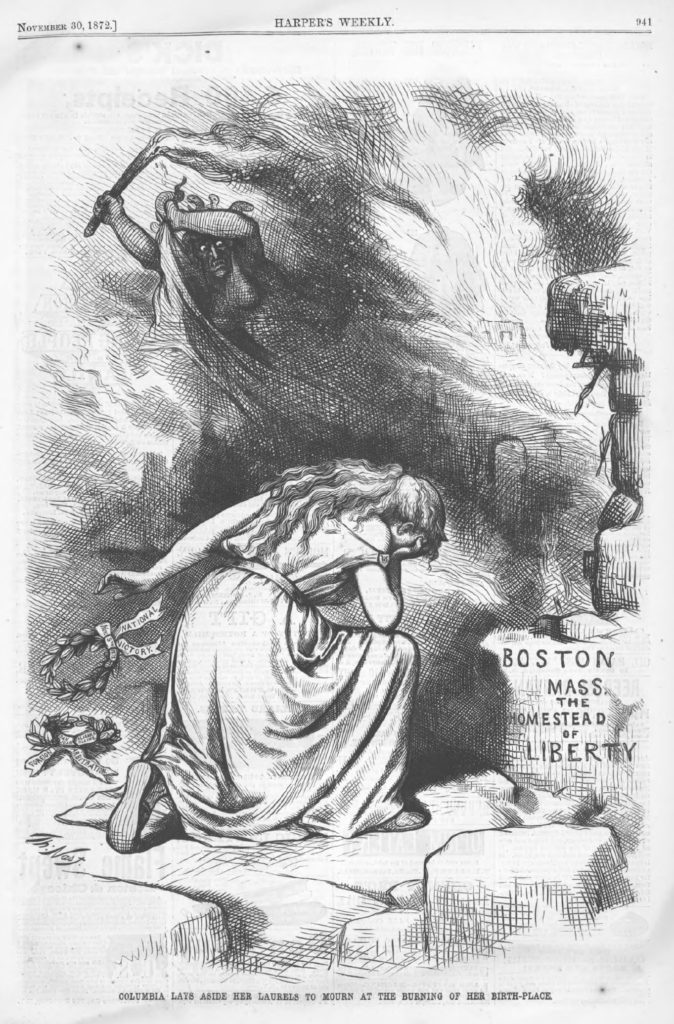

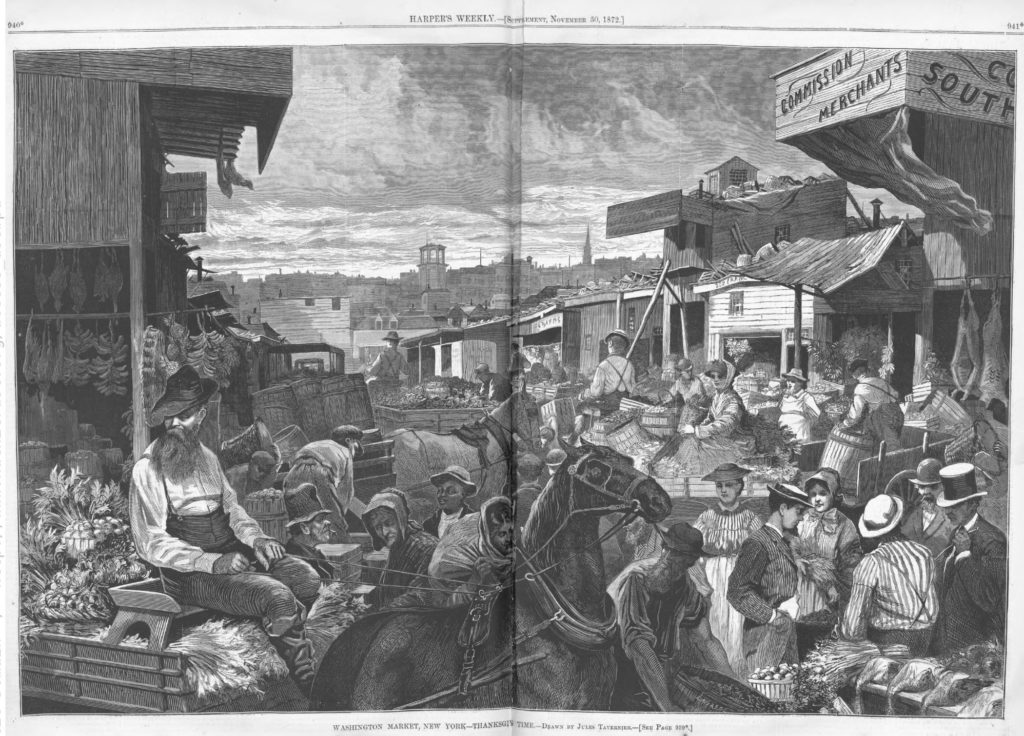

That was on October 11th. On November 9th and 10th the Great Boston Fire of 1872 ravaged about 65 acres of downtown Boston. At least 30 people died, including 12 firefighters; 776 building were destroyed. In its November 30, 1872 Supplement Harper’s Weekly provided some Thanksgiving content, but the main part of the newspaper focused on the Boston fire, at least with its pictures. Here’s a sample.

From Harper’s Weekly Supplement November 30, 1872:

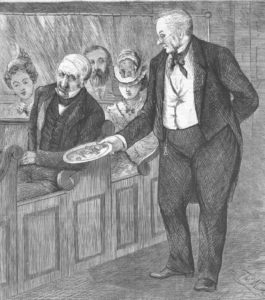

THE CHEERFUL GIVER.

That Heaven loves a cheerful giver is a saying as old as the human race; and that a gift is valued by the giver’s heart and not by its amount is beautifully illustrated by the parable of the poor widow’s mite. There is an excellent story of a rich but very stingy old Scotchman who once accidentally laid a guinea in place of a penny in the contribution box as it was passed round the church. He attempted to take it back, but was prevented by the vigilant deacon, who refused to give up anything that was “on the Lord’s plate.” “Weel, weel,” he grunted, as he leaned back in his pew, “I’ll get credit for it in heaven.” “Nae, Jamie,” said his friend the deacon, “ye’ll no get credit in heaven for ony thing but the penny ye thought to gie.”

At this season of the year, when the nation is called upon to offer thanks to Providence for peace, for abundant harvests, for general prosperity in commerce and all the various branches of industry, the poor should be remembered with special tenderness and liberality. We are apt to be spasmodic in our charities. A great disaster, like the fires which desolated Portland, Chicago, and Boston, an earthquake which lays waste a populous city and fills a land with terror, rouses us to extraordinary efforts on behalf of the sufferers. This is right, certainly; but we are very apt to forget that we have the poor with us always, and that hundreds and thousands right about our own doors are constantly suffering from want. The blessed summer-time affords them a respite from the sharper pangs of poverty; but winter brings them all – hunger and cold, sickness and death. Let those to whom Providence has given wealth, whose homes are full of comfort and plenty, think of the poor who have no “Thanksgiving.” Happy the man who is not only thankful for himself, but that he has the means of making others happy!

In its Thanksgiving coverage a New York City paper also stressed charity. From the November 29, 1872 issue of The New York Herald (page 4):

Thanksgiving and its Observance.

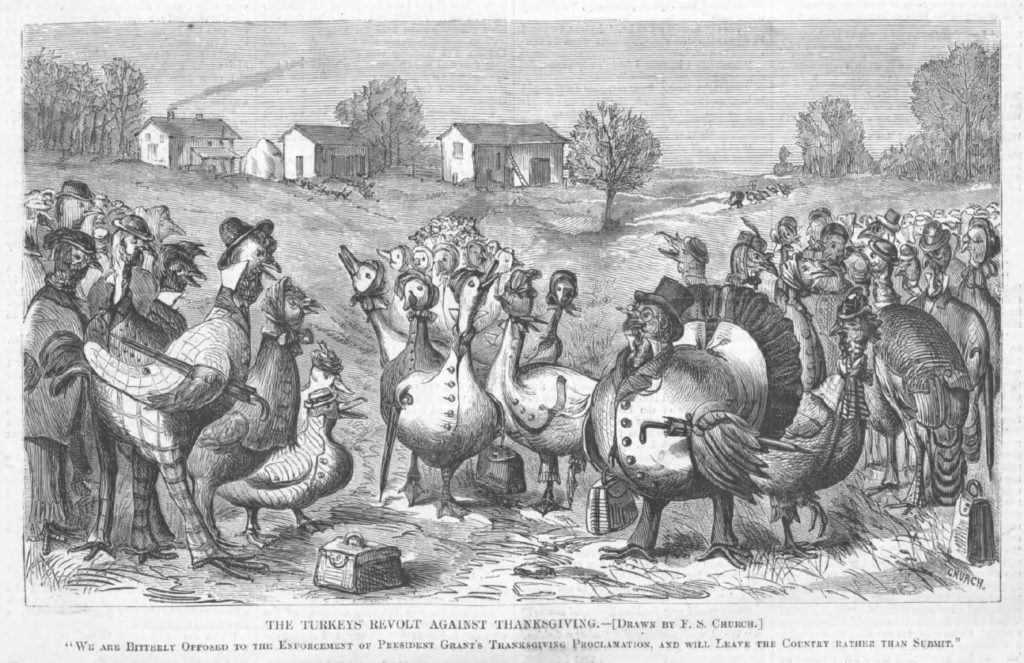

In the homes of the people and in the churches of the various religious denominations there was yesterday a more general observance of Thanksgiving Day than on any former occasion. As time rolls by the solitary religious holiday which has a national interest becomes invested with more interest in the popular mind, and its associations are hallowed by the memories, gay or sad, which the past has entwined with it. We are naturally inclined to be retrospective, and even the most go-ahead Yankee must sometimes pause in his career to look back with regret over the waste of time. In the bustle of our feverish life there are few opportunities to cultivate those gentle and tender memories which spring up amid time-honored celebrations with their scenes of innocent festivity into which tradition has woven that charm which antiquity alone can give – a feeling difficult to account for, that is yet the very essence of our enjoyment. Like all other human institutions time is exerting its influence over Thanksgiving Day, and people are beginning to associate with it more and more the idea of a festival. The traditionary turkey and the assembled guests enter more into our conceptions of it than the more solemn rites of religion. These, however, are not neglected, though the growth of a social and even a fantastical tendency in the celebration of the day is becoming more marked year by year. Perhaps the most pleasing and humanizing observance of the day is the custom of assembling the poor and wretched in the various charitable institutions of the city and making the day for them one of unusual happiness – a day to be remembered as the sad year advances through its weary round, a cycle of misery, with one recurring, bright joyous day, when the tears of the wretched are dried by the kind, charitable souls who spread an annual feast for the poor. It will be soon by the accounts published elsewhere that the entertainment of poor children was carried out pretty generally. The religious bodies and charitable institutions seemed to vie with each other in the extent to which this feature was carried, and in some instances as many as fifteen hundred poor children sat down to enjoy the substantial fare provided for them by the kindness and thoughtfulness of the more prosperous part of the community. Of all modes of returning thanks to the beneficent Creator for the blessings He has bestowed on the nation and on individuals, this tender charity toward the suffering ones will be most acceptable to Him who loves the poor. Nor can the effect of such reunions as those that mark the celebration of Thanksgiving and bring the wretched into contact with their happier fellow citizens fail to exercise a most healthy influence on the moral tone of those who are most exposed to temptation. It is well that the young ones whose fate has been cast in the midst of suffering and misery and vice should learn that the rich and prosperous sympathize with them and are willing to aid them in the battle of life. And these pleasant and humanizing reunions let in the light of hope on the dark spots of our civilization where else there would be nothing but gloom and despair. We must not estimate the value of the good done by this gathering together of the children of misfortune by the mere physical pleasure which a good dinner affords them, but rather by the moral effect on the children that is exercised by the hope of a brighter future, and the knowledge that in their darkest hour of suffering they will meet sympathy and support from their fellow men if only they will strive to merit it.

On its November 29, 1872 front page, The New York Times mentioned church services and charity. One of the charitable dinners was held at the Union Home and School for the Orphans of Soldiers and Sailors. Church service and possibly some music performed by the children, were also part of the exercises. The “fantasticals,” apparently forerunners of the “maskers” of the early 20th century, were out on the streets of Manhattan, wearing their masks and costumes. The paper reported on “Thanksgiving in England”. Cyrus W. Field gave a banquet at the Buckingham Palace Hotel to celebrate American Thanksgiving Day. Prime Minister William E. Gladstone addressed the gathering.