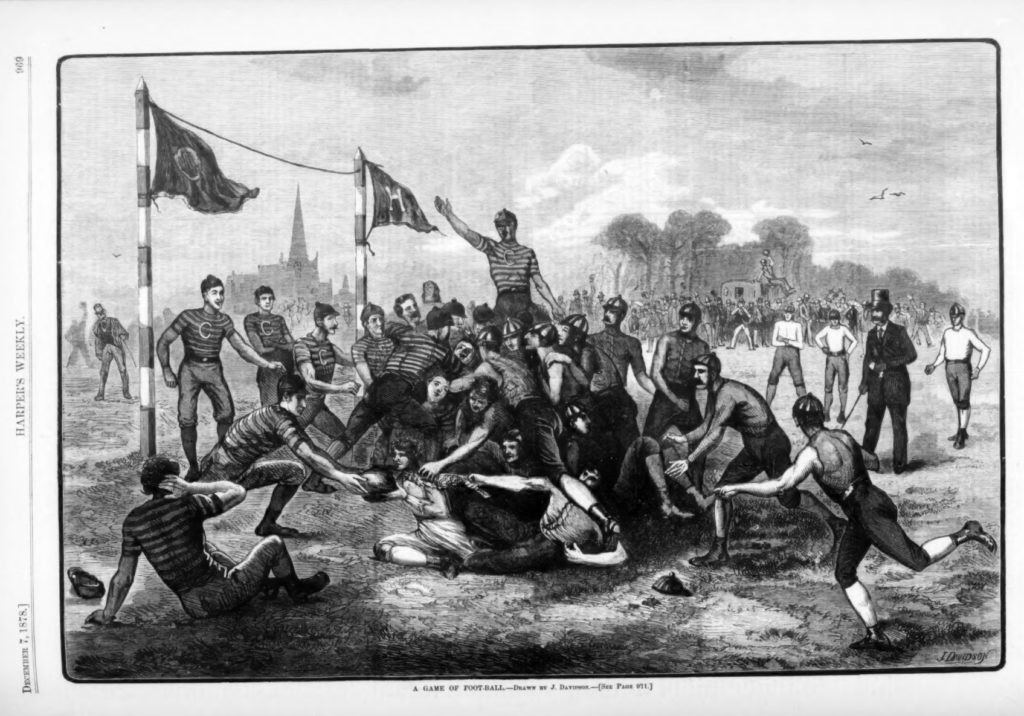

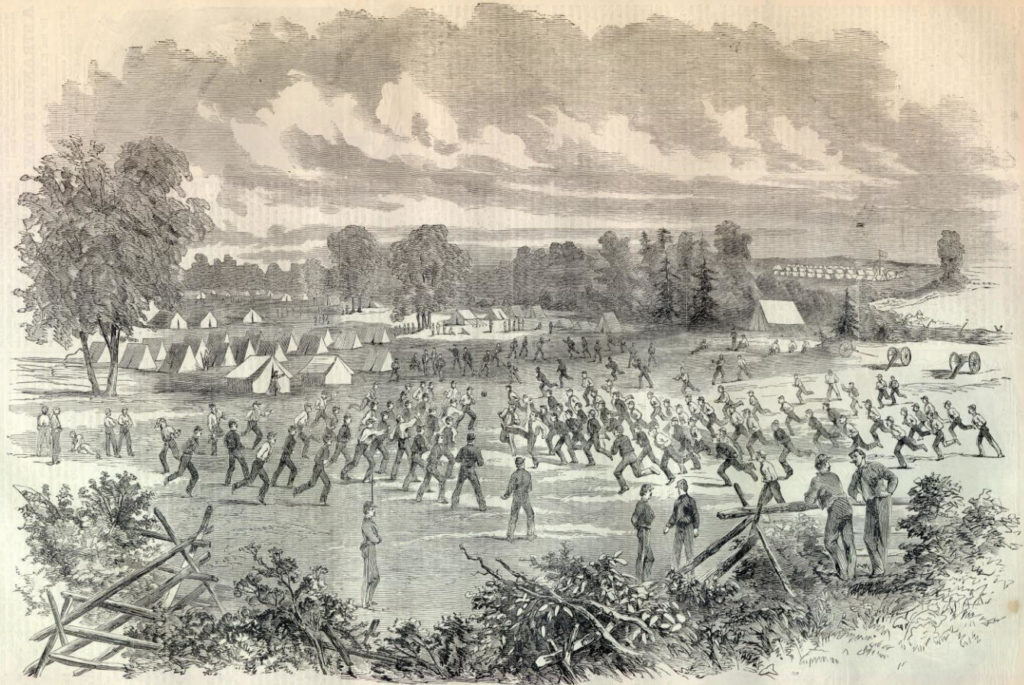

“CAMP JOHNSON, NEAR WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA-THE FIRST MARYLAND REGIMENT PLAYING FOOT-BALL BEFORE EVENING PARADE.” (1861)

Lately I’ve been in the habit of visiting the Pilgrim Hall Museum as November makes its annual return. This year I checked out Thanksgiving Touchdown, an article that describes the connection between American football and Thanksgiving and even touches on the American Civil War:

“A very crude game of ball-kicking was being played at East Coast colleges, such as Harvard and Yale, in the 1840s or before. Most colleges outlawed the game in the early 1860s – the tensions that eventually led to the Civil War were causing divisions on campus and a game like football, very physical and almost totally without rules, could easily erupt into violence. Perhaps because of that very physicality and flexibility, however, football remained popular with college men.

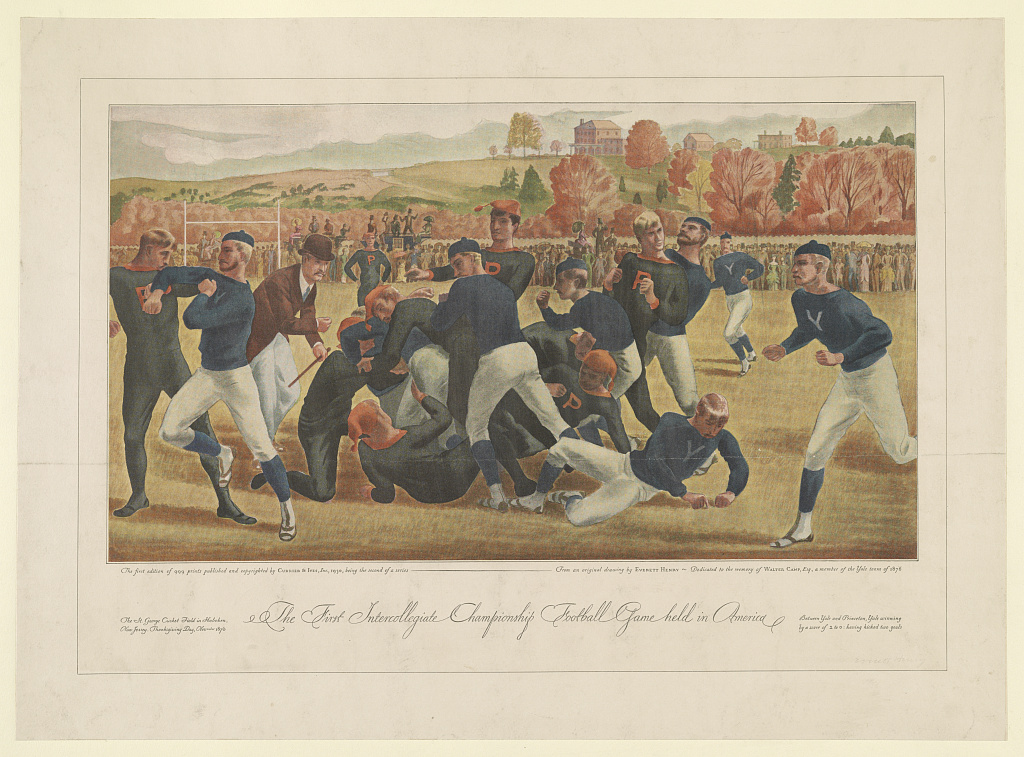

“After the Civil War, football officially returned to college campuses. The first intercollegiate game was played in 1869 between Princeton and Rutgers. There were 25 players to a side and the ball could be kicked or head-butted – but not carried.Rutgers won that first game 6 to 4; a rematch one week later was won by Princeton, 8 to 0.”

In 1876 “Harvard, Columbia, Yale, Princeton and Pennsylvania formed the Intercollegiate Football Association. The Association agreed to use the Harvard rules – and agreed that the two strongest teams would meet each year on Thanksgiving Day in New York City in a game that would determine the championship.” Yale beat Princeton in the 1876 Thanksgiving game. [The Harvard rules included the innovation that players could run with the ball. Harvard got that rule from Canada’s McGill University.]

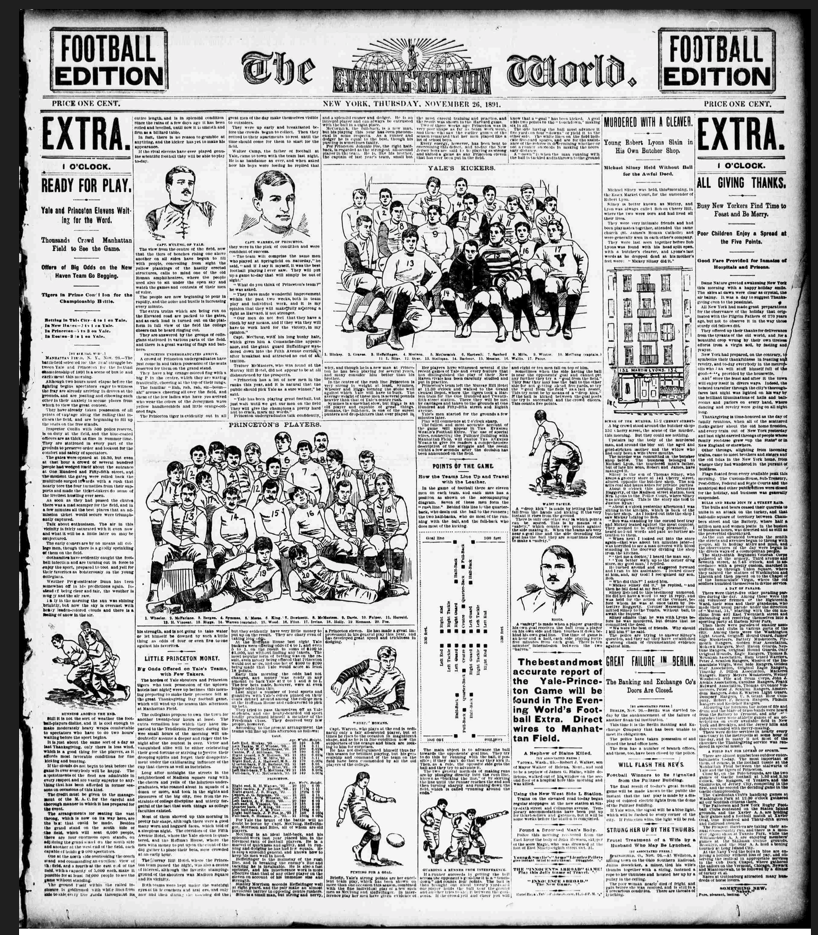

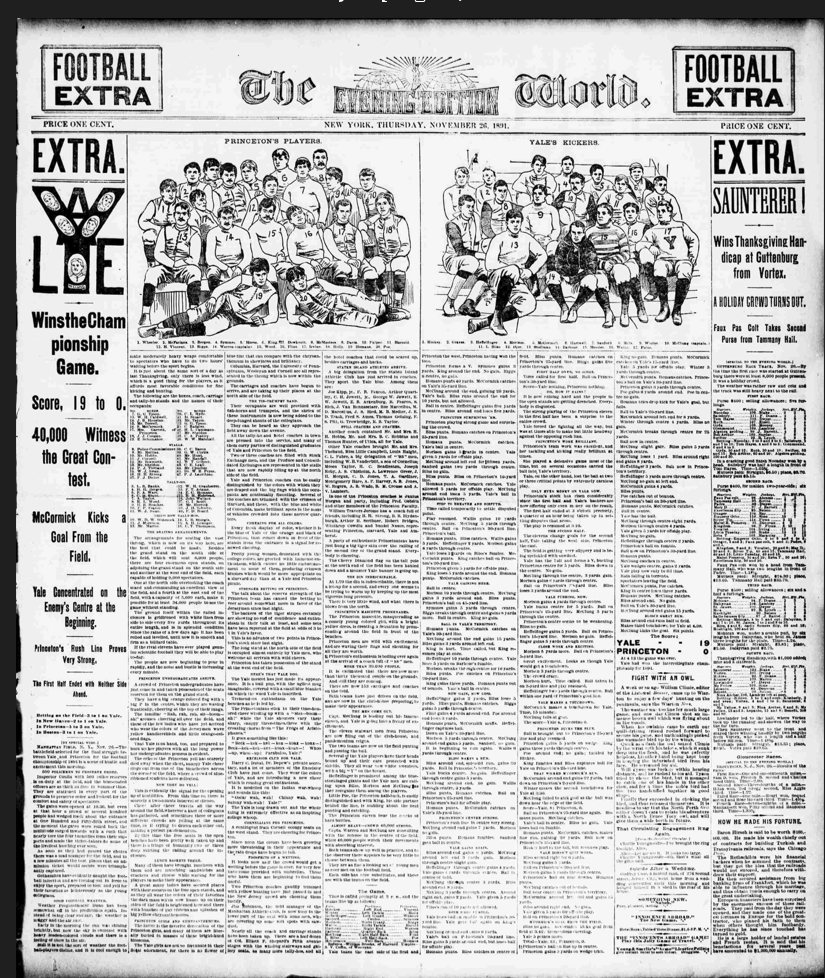

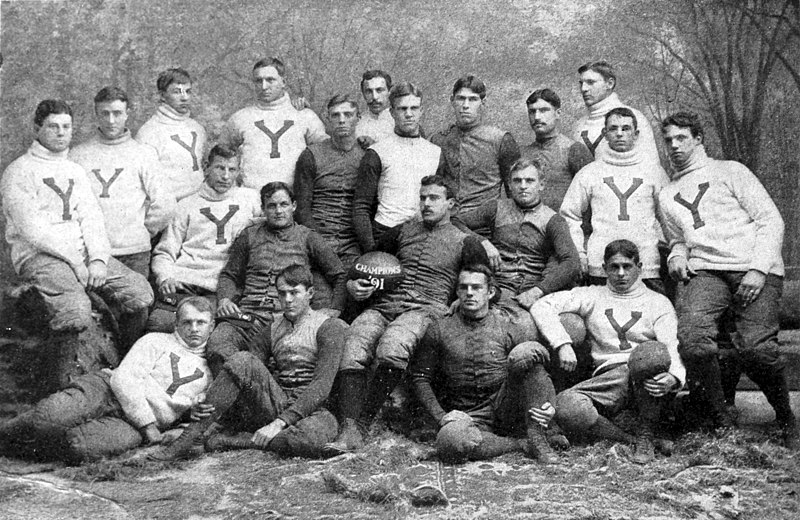

The Thanksgiving Day championship continued in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1891 Yale and Princeton were back at again. The big game was played on Manhattan Field.

Page 1 of the 1:00 PM edition of The Evening World Football Extra was full of information about the game and football in general. Yale was heavily favored. The Pulitzer Building was going to flash the game’s result from its dome: blue electric light if Yale won, red if Princeton managed to overcome the odds.

It was a blue light. Even though the game was scoreless at halftime, Yale won 19-0. A later Evening Edition Football Extra provided the final score and included a play-by-play account of the game. Point values were different than today: field goal = 5 points, touchdown = four points, and the kick after touchdown = two points:

______________________________

In 1860 church services with long sermons were a major part of Thanksgiving Day in the New York City area. The Football Extra noted some changes thirty years on. From The Evening World Football Extra Edition November 26, 1891 page 2:

THE THANKSGIVING OF TO-DAY.

Thanksgiving Day resembles Fourth of July not only in the respect that it comes once a year, but in that it is now, thanks to college football and other regular events of the day, accompanied by a good deal of hurrah.

It is not the Thanksgiving of old that we celebrate generally in these times. There are exercises incident to the day which might prove shocking to some good men and women of earlier generations, who accepted this annually recurring occasion as a sort of extra Sunday. But this would only because of the radical change of custom.

It has not hurt Thanksgiving Day to put dash and sport into its observance. Its conversion into a real red-letter day has nothing of the spirit of irreverence. Only a hopeful, healthful people will care for or indulge in active, blood-stirring sports. And people who are healthy and hopeful are, perforce, thankful, though they may not say it in so many words.

The Thanksgiving of to-day is a broader, more cheerful day than that of our grandfathers. The man who has no family reunion to attend, no family board to sit down to is no longer out of all place for the time being. The diversity of entertainment offered indoor and out has something for everybody, and thankfulness need not in anybody’s breast be drowned out by loneliness or homesickness.

THE GAME OF FOOTBALL.

The Thanksgiving dinners of a great many people will be late to-day because those people insist on staying to the very last kick in the great Yale-Princeton football game. But how appetites will be sharpened even by a spectatorship at that stirring struggle at Manhattan Field, and how enjoyment of the feast will be heightened by the lively flow of the aftertalk based upon the game.

And for the participants? Well, the one side must be inspired by the sense of victory won and championship attained. The other – pshaw! It will be a great game lost, but they will have made it go hard, and they will have a long time before next Thanksgiving in which to prepare for a possible reversal of the result.

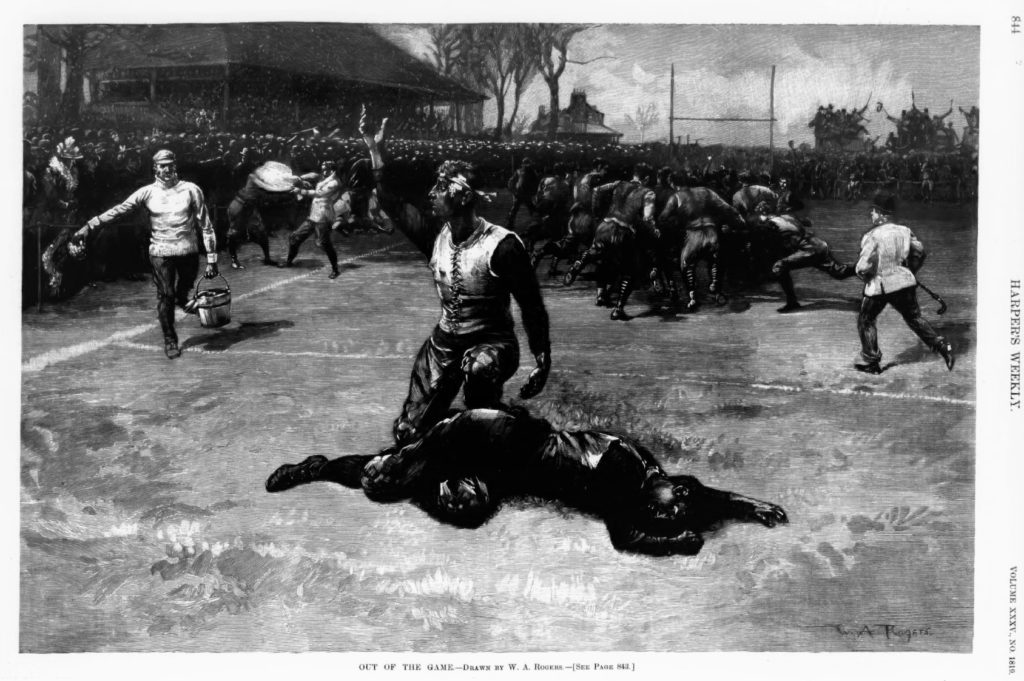

Football is a game worthy of any nation’s holidays, as American college boys play it. Brain and brawn both have place in it. It is a game calculated to develop both manliness and muscle. Long may it hold its place on the calendar of sports and long may its exponents live to vent their enthusiasm over the exploits of their successors when their own playing days are over.

The Pilgrim Hall Museum football article from above quoted a Harper’s Weekly piece from 1891 that thought that the new Thanksgiving, at least in New York City, was a big improvement on the old. People could get out and watch a football game instead of being trapped at the family dinner table, listening to an elderly relation recount, once again, the “old story of the roast pig he stole the night before Gettysburg…”

Page 1 of the Football Extra reported that Thanksgiving Day wasn’t entirely feasting and revelry in 1891. A military unit continued a more solemn tradition:

The Sixty-ninth Regiment Veteran Corps gathered at the armory, Third avenue and Seventh street, at 7.45 o’clock, and in accordance with a pretty custom, marched in uniform up through Union Square, where they saluted the statues of Washington and Lincoln and then passed on to the Chapel of the Immaculate Virgin, where the old soldiers humbled themselves in divine service.