The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. was dedicated on Memorial Day a century ago (five score years). From the May 31, 1922 issue of The New York Times:

WASHINGTON, May 30. – The Lincoln Memorial magnificent and compelling in its purity of line and simplicity, was dedicated this afternoon.

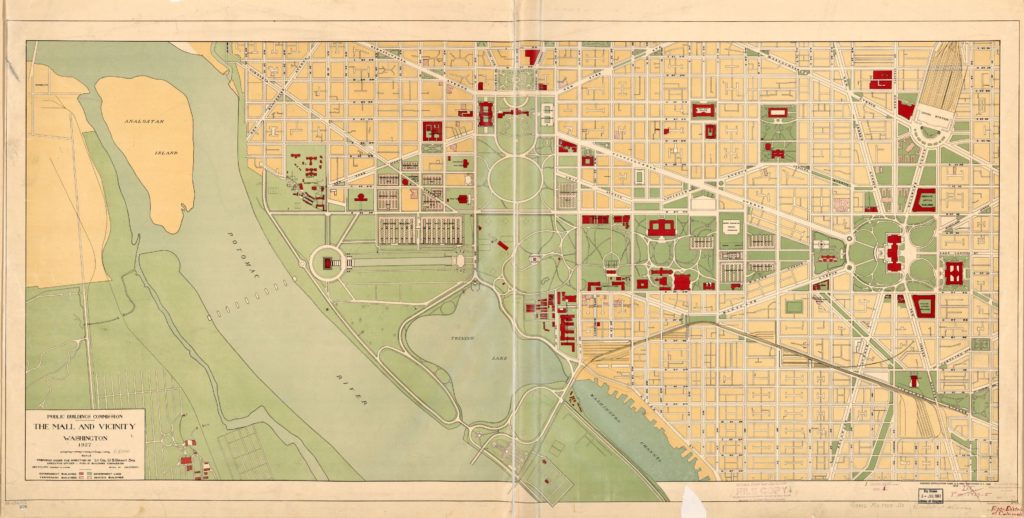

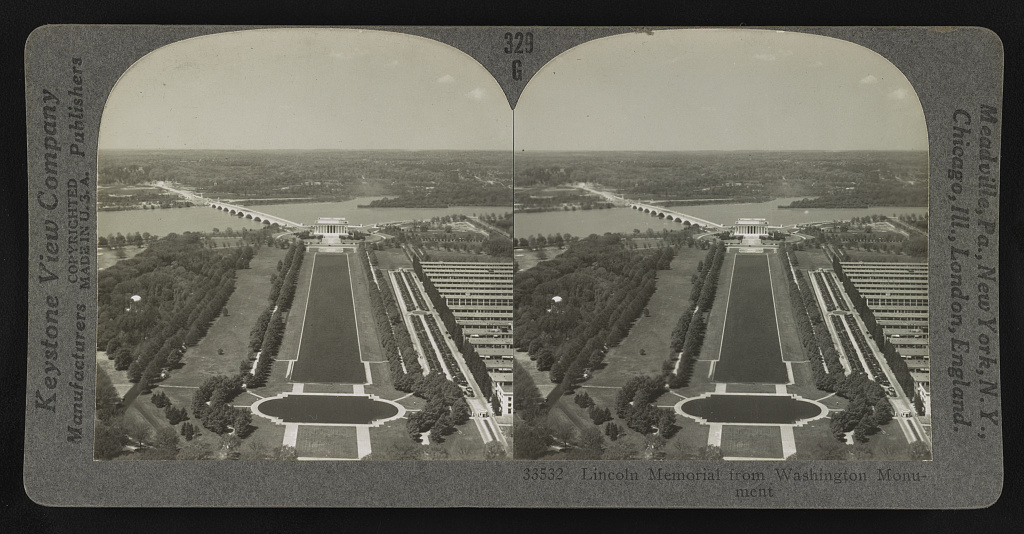

For ten years this white marble shrine with its massive Doric columns, has been slowly rising on the banks of the Potomac at the western end of the Mall, where once was a dismal, marshy waste. Its completion gives to Washington three dominating structures, each different but each fitting into a harmonious whole, on the Mall. At the east is the imposing dome of the Capitol, between the perfectly proportioned Washington Monument points upward a granite index finger, and to the west, glistening like a flawless gem in its setting, stands the memorial that perpetuates in marble, sculpture and fresco, the spirit of Abraham Lincoln.

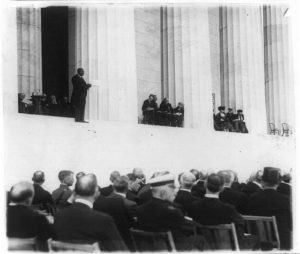

Today, fifty-seven years after the tragedy in Ford’s Theatre, the Civil War tunes, the martial airs of Spanish War days and the stirring songs of the A. E. F. sounded through Washington streets as veterans of three wars marched to visit the graves of their dead. In the afternoon these processions converged at the Lincoln Memorial, where Chief Justice Taft, as Chairman of the Memorial Commission, turned over the building to the Government, represented by President Harding.

Thus a palfietic [?] handful of the fast dwindling survivors of the Civil War, some of whom knew Lincoln, had the satisfaction of witnessing within their lifetime the dedication of a marble symbol of Stanton’s announcement that the Great Emancipator belongs to the ages.

Blue and Gray Join in Tribute.

The ceremonies were in keeping with the simplicity of the memorial. Grand Army men, led by Lewis S. Pilcer [Pilcher], Commander- in-Chief, presented the color and laid symbols of the army and navy at the foot of the structure. Across the aisle sat gray-clad Confederate veterans, and from their seats they could look over the Potomac to the Virginia hills, where Arlington, once the home of Robert E. Lee, nestles among the trees. Robert R. Moton, President of Tuskegee Institute, paid tribute to Lincoln in the name of 12,000,000 negroes. Edwin Markham read the revision of his poem, “Lincoln, the Man of the People.”

Chief Justice Taft, under whose administration as President the memorial was begun, gave a short account of the labors of the Memorial Commission and delivered the building into the Government’s keeping. President Harding then accepted the memorial and drew a lesson from Lincoln’s steadfastness under criticism, eulogizing him as not a superman but as a “natural human being with the frailties mixed with the virtues of humanity.” The Invocation and benediction were delivered by the Rev. Wallace Radcliffe, pastor of the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, where Lincoln worshipped.

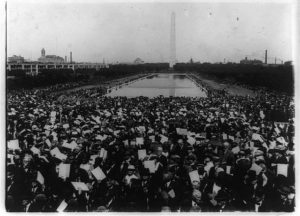

Thousands assembled at the approaches to the memorial and the crowd extended down along the quarter-mile long mirror basin in which the Washington Monument was reflected with the background of a cloudless sky. Amplifying devices, cleverly concealed so that they did not detract from the beauty of the memorial, carried the speakers’ voices several hundred yards, and by the same means the speeches were sent broadcast by radiophone.

Wilson Unable to Attend.

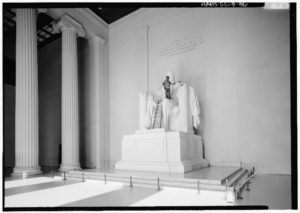

Just back of the east colonnade were seated the official members of the party, the president and Mrs. Harding, members of the Cabinet and their wives, Robert T. Lincoln, the martyred President’s son and Mrs. Lincoln; members of the Memorial Commission; Henry R. Bacon, architect of the memorial; Daniel Chester French, sculptor of the heroic seated figure of Lincoln placed in the centre of the memorial, and Jules Guerin, designer of the allegorical frescoes. Places were reserved for former President and Mrs. Wilson, but early this morning Mr. Wilson sent word to Chief Justice Taft that he would be unable to attend.

To the left along the colonnade were members of the Supreme Court and to the right Foreign Ambassadors and their staffs. On the terrace were other members of the Diplomatic Corps and members of both houses of Congress.

A conspicuous figure at the end of the row of Ambassadors was Otto Wiedefelt, the German Ambassador, who presented his credentials last week. He arrived late and alone and followed the proceedings with close attention, occasionally leaving his seat and standing against one of the columns to obtain a better view of the speakers and the crowd beneath.

There were two incidents that gave temporarily a touch out of keeping with the dignity of the ceremonies. One was at the end of the exercises, when the Chief Justice requested the people in the audience to remain in their places until the President proceeded to his car, whereupon several dozen members of

Continued on Page Three

According to documentation at the Library of Congress, Robert Russa Moton began his Lincoln memorial speech by looking back to 1620, when the Pilgrim Fathers “laid the foundations of our national existence upon the bed-rock of liberty.” Since then liberty had been the common bond of “our united people,” and Americans had fought to extend freedom throughout the world. In his second paragraph Dr. Moton looked back a year before the Pilgrim landing, when a ship landed in Jamestown, Virginia that brought the first African slaves to North America. Those slaves were “pioneers of bondage, a bondage degrading alike to body, mind, and spirit.”

Those two contrasting principles eventually led to the costly Civil War, which, with Lincoln at the helm, the Union fought to win, and which, at its conclusion, Lincoln’s life was sacrificed. Dr. Moton agreed that Lincoln fought the Civil war to keep the Union together, but he also fought it to free the slaves. Despite doubt and adversity, President Lincoln “put his trust in God and spoke the word that gave freedom to a race, and vindicated the honor of a nation” by making it live up to the principle of the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal.

In answering the question of whether Abraham Lincoln’s sacrifice was worth it, Mr. Moton first pointed out the loyalty of African-Americans, from Crispus Attucks killed during the American Revolution to the black doughboys who had recently sacrificed their lives in France. He used statistics to detail all the progress African-Americans had made in less than sixty years of freedom. Lincoln’s sacrifice was worth it because the black race “had taken full advantage of its freedom to develop its latent powers for itself and for the nation.” There was still more to do, but progress was being made: “As we gather on this consecrated spot, his spirit must rejoice that sectional rancours and racial antagonisms are softening more and more into mutual understanding and effective cooperation.” Dr. Moton hoped that the nation would be dedicated anew to the task for which Lincoln died – “equal opportunity and unhampered freedom” for all citizens, even the most humble, regardless of color or creed.

_____________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________