From the March 2, 1872 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

A WOMAN IN THE PULPIT.

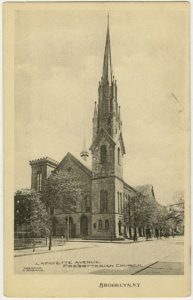

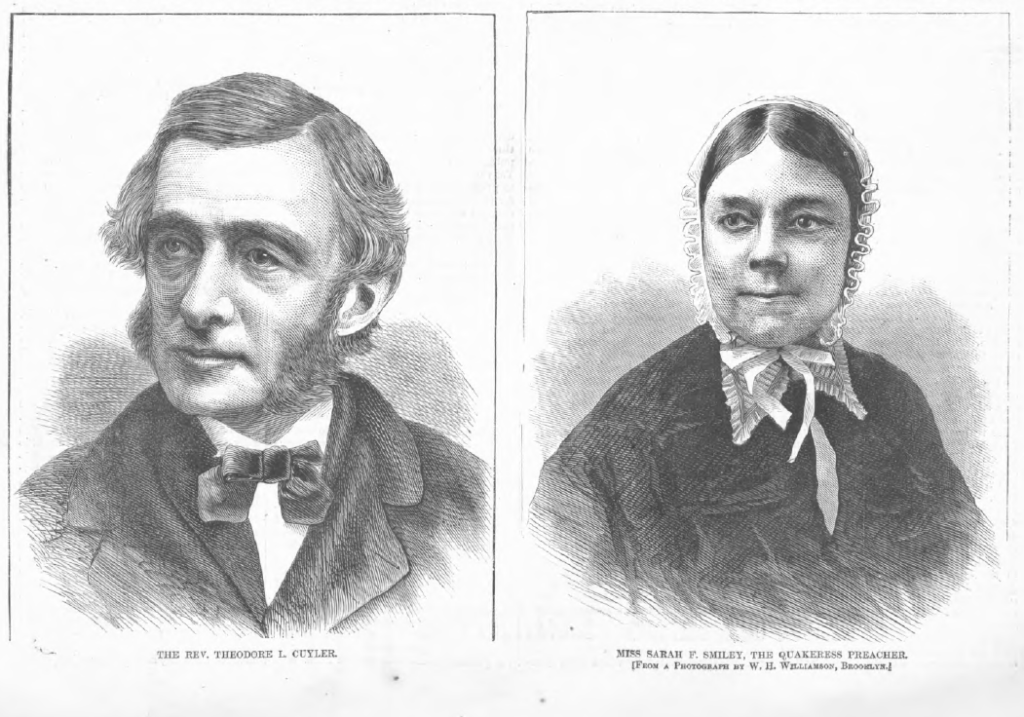

THE good Presbytery of Brooklyn have been greatly scandalized of late by the appearance of Miss SARAH F. SMILEY, a Quakeress preacher, in the pulpit of the Rev. THEODORE L. CUYLER, of the Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church. Miss SMILEY, as we learn from the daily papers, preached a most excellent and acceptable sermon, and none of the congregation took the least offense at the unusual spectacle of a woman in the pulpit. Not so, however, the Presbytery. Alarmed and apparently horrified at the innovation, they took immediate steps to call Dr. CUYLER to account, and a meeting of that body was held to consider what action, if any, should be taken in reference to his conduct. The moderator, the Rev. Joseph M. GREEN, expressly stated that the meeting was not called in an unfriendly spirit toward Dr. CUYLER or his church, but chiefly to ascertain the sense of the Presbytery upon the following questions: “First, shall the Presbyterian Church open corresponding relations with the Quaker Church, or Society of Friends? second, shall women be ordained as preachers? and third, shall the Presbyterian Church change its practice and modify its interpretation of Holy Scripture so as to recognize the right of women to ordination?”

At this meeting Dr. CUYLER made a full statement of the circumstances under which Miss SMILEY was invited to preach in the church of which he is pastor; and, without entering into the merits of the question at all, we do not hesitate to say that his statement was exceedingly creditable both to himself and Miss SMILEY. Dr. CUYLER’s relations with the Society of Friends are of the most intimate and cordial character. He long resided in a Quaker family. A short time since he received a courteous and fraternal invitation from the Friends to address one of their revival meetings in Brooklyn. He had accepted this invitation, had been welcomed to their preacher’s bench, or pulpit, and at the close of his discourse one of their most eminent ministers rose and said, with feeling: “We arein full accord with all that has fallen from our esteemed and beloved brother, THEODORE CUYLER. “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.’”

In response to this invitation Dr. CUYLER invited Miss SMILEY, to whose discourses he had listened with deep interest, to address his own congregation on a Sunday evening. He announced the fact to his people in advance, and not a single member of the church expressed the slightest objection. “On the following Sunday evening,” says Dr. CUYLER, “Miss SMILEY was conducted to the Lafayette Avenue pulpit by the pastor. She came there in the decorous Quaker garb, and clothed upon with humility as becometh the saints.” Unlike some of the more extravagant ladies of our own congregation, she obeyed the Pauline precept, ‘I will that the women be not adorned with gold, or pearls, or costly array.” After the usual opening services I introduced my friend to the very large, intelligent, and deeply solemn and attentive auditory. I said: ‘My esteemed friend and co-worker in the service of Christ, SARAH F. SMILEY, will now give to us such a Gospel message as she may have to offer.” Dr. Hodge, of Princeton–Dr. Hodge, of Christendom—says that St. PAUL saluted PRISCILLA as his ‘fellow-laborer in the promotion of the Gospel.” As such I introduced the good Quakeress, who having edified me with her pen, I was quite certain would edify my congregation from her lips. She used no text, but took the vision of JACOB at Bethel as her theme, and illustrated from it the upward steps of the soul from sin toward holiness and heaven; the steps being repentance of sin, faith in the atoning Saviour, and so forth. Her address, or discourse, was weighty, solemn, Scriptural, orthodox, tender, and melted some men to tears whom I have never seen so much moved before. She offered a devout and reverent prayer, a hymn was sung, and I concluded with the apostolic benediction.”

On the conclusion of Dr. CUYLER’s address an animated debate took place upon the subject of the meeting. It was not quite certain that the Presbytery knew exactly what they had come together for, or what was the real nature of Dr. CUYLER’s offense. The Rev. Dr. SPEAR and the Rev. Dr. TALMAGE and the Rev. ALFRED TAYLOR contended that the Presbytery had no occasion to act in the matter; but the Rev. Dr. VAN DIKE, the Rev. Mr. PATTON, and others took the opposite view, and spoke strongly in condemnation of women as preachers. What they had to say on the subject was most plainly and succinctly stated by the Rev. Dr. M’CLELLAND, a blind Scotch clergyman. He contended that preaching by women was not sanctioned by church law nor by the Scriptures. Not from the beginning of Genesis to the end of Malachi could a single instance be found where a woman was installed into ordinary ministerial functions. That record covered 3500 years, and during all that time only three prophetesses were mentioned, and these clearly had qualified powers. Thus you have an average of one in 1200 years. The exceptional cases, he argued, established the rule against the women. In the New Testament he contended that the authority was all against the women. The Christian church, he remarked, was founded on the synagogue, not on the temple, and who does not know that no woman was ever permitted to teach in the synagogue? Both history and presumption were against women preaching, and he concluded by contending that direct prohibition was against it also.

At length, after a long and desultory debate, the following expression of opinion was adopted: “The Presbytery having been informed that a woman has preached in one of our churches on Sabbath, at a regular service, at the request of the pastor, with the consent of the session; therefore,

“Resolved, That the Presbytery feel constrained to enjoin upon our churches strict regard to the following deliverance of the General Assembly:

“Meetings of pious women by themselves for conversation and prayer we entirely approve. But let not the inspired prohibitions of the great Apostle as found in his epistles to the Corinthians and to Timothy be violated. To teach and to exhort, or to lead in prayer in public and promiscuous assemblies, is clearly forbidden to women in the Holy Oracles.”

The Presbytery then adjourned, without without having brought Dr. CUYLER or his church to a sense of the enormity of their offense in listening to a sermon by a Christian woman.

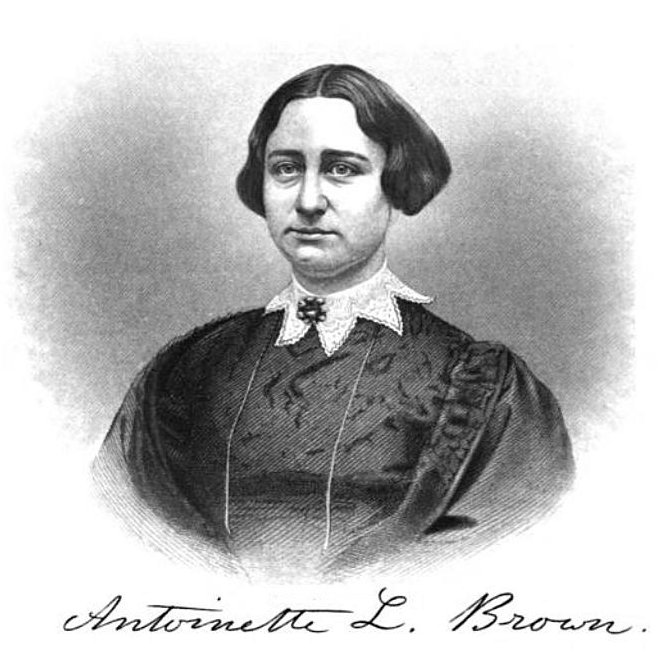

Miss SMILEY, of whom we give a portrait on this page, is a woman of maturity, of sweet Christian character, and gifted with extraordinary powers as a preacher. She has passed her life in doing good with the talents God has given her. Two years ago she made a “religious visit” to Great Britain, and was not only honored by the British “Yearly Meeting” of Orthodox Friends with fullest fellowship, but was cordially welcomed by eminent persons of all denominations. The most brilliant man of letters in Scotland (himself a Presbyterian) sought her friendship, and opened up to her some of his spiritual difficulties; and as PRISCILLA of old expounded to the eloquent Apollos “the way of God more perfectly,” so this gifted woman brought her wise counsels to the man of genius. After the war was over she left her cultured home and went as a voluntary missionary to the emancipated slaves of the South. She taught and addressed both males and females. Those liberated bondmen “heard her gladly.” And, says Dr. CUYLER, I do not believe that if the Apostle PAUL had stood by her side he would have said, “Woman, it is a shame for you to preach Jesus Christ to these poor negroes.” Miss SMILEY is a native of Vassalborough, Maine, and is now resident in Baltimore, Maryland.

The Rev. THEODORE L. CUYLER, of whom also a portrait is given on this page, was born at Aurora, on Cayuga Lake, in 1822. His father, a lawyer of reputation and ability, died when he was only four years old. He graduated from Princeton College at the age of nineteen, and from the Princeton Theological Seminary three years later. Since then he has been settled at Burlington, Trenton, the Market Street Church, New York, and is now pastor of the Lafayette Avenue Church, in Brooklyn, whose member ship is over 1400. The church edifice seats 2000 persons.

Dr. CUYLER is not only an eloquent preacher, but a very accomplished and successful writer. He has contributed over 1500 articles to various religious papers and magazines. The ensuing spring he will visit Scotland as the delegate of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church to the General Assemblies of Scotland and Ireland. His course in regard to the Quakeress preacher is generally approved by the religious and secular press of the country.

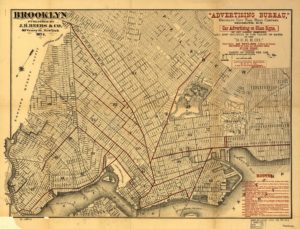

The Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church still exits. According to its website, “The church was founded in 1857 by a number of prominent Brooklyn families residing in Clinton Hill and Fort Greene.

They sought Rev. Dr. Theodore Cuyler, a well-known author and vibrant preacher as their first Pastor. To lure him from Manhattan, they acceded to his request by building a church seating 2,000. Ground was broken in 1860 and the building was completed in 1862, with additions in 1885 and 1917.”

In Recollections of a Long Life An Autobiography (at Project Gutenberg) Theodore Cuyler included reminiscences about his boyhood near Cayuga Lake and the Sarah Smiley incident much later on:

BOYHOOD AND COLLEGE LIFE

Washington Irving has somewhere said that it is a happy thing to have been born near some noble mountain or attractive river or lake, which should be a landmark through all the journey of life, and to which we could tether our memory. I have always been thankful that the place of my nativity was the beautiful village of Aurora, on the shores of the Cayuga Lake in Western New York. My great-grandfather, General Benjamin Ledyard, was one of its first settlers, and came there in 1794. He was a native of New London County, Ct., a nephew of Col. William Ledyard, the heroic martyr of Fort Griswold, and the cousin of John Ledyard, the celebrated traveller, whose biography was written by Jared Sparks. When General Ledyard came to Aurora some of the Cayuga tribe of Indians were still lingering along the lakeside, and an Indian chief said to my great-grandfather, “General Ledyard, I see that your daughters are very pretty squaws.” The eldest of these comely daughters, Mary Forman Ledyard, was married to my grandfather, Glen Cuyler, who was the principal lawyer of the village, and their eldest son was my father, Benjamin Ledyard Cuyler. He became a student of Hamilton College, excelled in elocution, and was a room-mate of the Hon. Gerrit Smith, afterward eminent as the champion of anti-slavery. On a certain Sabbath, the student just home from college was called upon to read a sermon in the village church of Aurora, in the absence of the pastor, and his handsome visage and graceful delivery won the admiration of a young lady of sixteen, who was on a visit to Aurora. Three years afterward they were married. My mother, Louisa Frances Morrell, was a native of Morristown, New Jersey; and her ancestors were among the founders of that beautiful town. Her maternal great-grandfather was the Rev. Dr. Timothy Johnes, the pastor of the Presbyterian Church, who administered the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper to General Washington. Her paternal great-grandfather was the Rev. Azariah Horton, pastor of a church near Morristown, and an intimate friend of the great President Edwards. The early settlers of Aurora were people of culture and refinement; and the village is now widely known as the site of Wells College, among whose graduates is the popular wife of ex-President Cleveland.

In the days of my childhood the march of modern improvements had hardly begun. There was a small steamboat plying on the Cayuga Lake. There was not a single railway in the whole State. When I went away to school in New Jersey, at the age of thirteen, the tedious journey by the stagecoach required three days and two nights; every letter from home cost eighteen cents for postage; and the youngsters pored over Webster’s spelling-books and Morse’s geography by tallow candles; for no gas lamps had been dreamed of and the wood fires were covered, in most houses, by nine o’clock on a winter evening. There was plain living then, but not a little high thinking. If books were not so superabundant as in these days, they were more thoroughly appreciated and digested.

My father, who was just winning a brilliant position at the Cayuga County Bar, died in June, 1826, at the early age of twenty-eight, when I was but four and one-half years old. The only distinct recollections that I have of him are his leading me to school in the morning, and that he once punished me for using a profane word that I had heard from some rough boys. That wholesome bit of discipline kept me from ever breaking the Third Commandment again. After his death, I passed entirely into the care of one of the best mothers that God ever gave to an only son. She was more to me than school, pastor or church, or all combined. God made mothers before He made ministers; the progress of Christ’s kingdom depends more upon the influence of faithful, wise, and pious mothers than upon any other human agency.

As I was an only child, my widowed mother gave up her house and took me to the pleasant home of her father, Mr. Charles Horton Morrell, on the banks of the lake, a few miles south of Aurora. How thankful I have always been that the next seven or eight years of my happy childhood were spent on the beautiful farm of my grandfather! I had the free pure air of the country, and the simple pleasures of the farmhouse; my grandfather was a cultured gentleman with a good library, and at his fireside was plenty of profitable conversation. Out of school hours I did some work on the farm that suited a boy; I drove the cows to the pasture, and rode the horses sometimes in the hay-field, and carried in the stock of firewood on winter afternoons. My intimate friends were the house-dog, the chickens, the kittens and a few pet sheep in my grandfather’s flocks. That early work on the farm did much toward providing a stock of physical health that has enabled me to preach for fifty-six years without ever having spent a single Sabbath on a sick-bed!

My Sabbaths in that rural home were like the good old Puritan Sabbaths, serene and sacred, with neither work nor play. Our church (Presbyterian) was three miles away, and in the winter our family often fought our way through deep mud, or through snow-drifts piled as high as the fences. I was the only child among grown-up uncles and aunts, and the first Sunday-school that I ever attended had only one scholar, and my good mother was the superintendent. She gave me several verses of the Bible to commit thoroughly to memory and explained them to me; I also studied the Westminster Catechism. I was expected to study God’s Book for myself, and not to sit and be crammed by a teacher, after the fashion of too many Sunday-schools in these days, where the scholars swallow down what the teacher brings to them, as young birds open their mouths and swallow what the old bird brings to the nest. There is a lamentable ignorance of the language of Scripture among the rising generation of America, and too often among the children of professedly Christian families.

The books that I had to feast on in the long winter evenings were “Robinson Crusoe,” “Sanford and Merton,” “The Pilgrim’s Progress,” and the few volumes in my grandfather’s library that were within the comprehension of a child of eight or ten years old. I wept over “Paul and Virginia,” and laughed over “John Gilpin,” the scene of whose memorable ride I have since visited at the “Bell of Edmonton,” During the first quarter of the nineteenth century drunkenness was fearfully prevalent in America; and the drinking customs wrought their sad havoc in every circle of society. My grandfather was one of the first agriculturists to banish intoxicants from his farm, and I signed a pledge of total abstinence when I was only ten or eleven years old. Previously to that, I had got a taste of “prohibition” that made a profound impression on me. One day I discovered some “cherrybounce” in a wine-glass on my grandfather’s sideboard, and I ventured to swallow the tempting liquor. When my vigilant mother discovered what I had done, she administered a dose of Solomon’s regimen in a way that made me “bounce” most merrily. That wholesome chastisement for an act of disobedience, and in the direction of tippling, made me a teetotaller for life; and, let me add, that the first public address I ever delivered was at a great temperance gathering (with Father Theobald Mathew) in the City Hall of Glasgow during the summer of 1842. My mother’s discipline was loving but thorough; she never bribed me to good conduct with sugar-plums; she praised every commendable deed heartily, for she held that an ounce of honest praise is often worth more than many pounds of punishment.

During my infancy that godly mother had dedicated me to the Lord, as truly as Hannah ever dedicated her son Samuel. When my paternal grandfather, who was a lawyer, offered to bequeath his law-library to me, my mother declined the tempting offer, and said to him: “I fully expect that my little boy will yet be a minister.” This was her constant aim and perpetual prayer, and God graciously answered her prayer of faith in His own good time and way. I cannot now name any time, day, or place when I was converted. It was my faithful mother’s steady and constant influence that led me gradually along, and I grew into a religious life under her potent training, and by the power of the Holy Spirit working through her agency. A few years ago I gratefully placed in that noble “Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church” of Brooklyn (of which I was the founder and pastor for thirty years) a beautiful memorial window to my beloved mother representing Hannah and her child Samuel, and the fitting inscription: “As long as he liveth I have lent him to the Lord.”

For several good reasons I did not make a public profession of my faith in Jesus Christ until I left school and entered the college at Princeton, New Jersey. The religious impressions that began at home continued and deepened until I united, at the age of seventeen, with the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ. As an effectual instruction in righteousness, my faithful mother’s letters to me when a schoolboy were more than any sermons that I heard during all those years. I feel now that the happy fifty-six years that I have spent in the glorious ministry of the Gospel of Redemption is the direct outcome of that beloved mother’s prayers, teaching example, and holy influence. …

A RETROSPECTIVE …

Another change for the better has been the enlargement of woman’s sphere of activity in the promotion of Christianity and of moral reform. As an illustration of this fact, I may cite a rather unique incident in my own experience. During the winter of 1872 I invited Miss Sarah F. Smiley, an eminent and most evangelical minister in the Society of Friends (and a sister of the Messrs. Albert and Daniel Smiley, the proprietors of the Lake Mohonk House) to deliver a religious address in my pulpit. The discourse she delivered was strong in intellect, orthodox in doctrine and fervently spiritual in character; the large audience was both delighted and edified. A neighboring minister presented a complaint before the Presbytery of Brooklyn, alleging that my proceeding had been both un-Presbyterian and un-Scriptural. The complainant was not able to produce a syllable of law from our form of government forbidding what I had done. Long years before, a General Assembly had recommended that “women should not be permitted to address a promiscuous assemblage” in any of our churches; but a mere “deliverance” of a General Assembly has no binding legal authority.

In my defense I was careful not to advocate the ordination of women to the ministry in the Presbyterian Church, or their installation in the pastorate. I contended that as our confession of faith was silent on the subject, and that as godly women in the early church were active in the promotion of Christianity (one of them named Anna having publicly proclaimed the coming Messiah), and that as the ministry of my excellent friend, the Quakeress, had for many years been attended by the abundant blessings of the Holy Spirit, my act was rather to be commended than condemned. The discussion before the Presbytery lasted for two days and produced a wide and rather sensational interest over the country. The final vote of the Presbytery, while withholding any censure of my course under the circumstances, was adverse to the practice of permitting women to address “promiscuous audiences” in our churches. Two or three years afterwards, a case similar to mine was appealed to the General Assembly and that body wisely decided that such questions should be left to the judgment and conscience of the pastors and church sessions. When the news of this action of the assembly reached us, the old sexton of the Lafayette Avenue Church hoisted (to the great amusement of our people) the stars and stripes on the church tower as a token of victory. It has now become quite customary to invite female missionaries, and other godly women, to address audiences composed of both sexes in our churches; the padlock has been taken off the tongue of any consecrated Christian woman who has a message from the Master. I invited Miss Willard and Lady Henry Somerset to advocate the Christian grace of temperance from my pulpit; and if I were still a pastor I should rejoice to invite that good angel of beneficence, Miss Helen M. Gould, to deliver there such an address as she lately made in the splendid building she has erected for the “Naval Christian Association.”

In its February 10, 1872 issue The Charleston Daily News published correspondence from New York City. The article reported on the Presbyterian “trial” of Reverend Cuyler for allowing a woman to preach from his pulpit and then went on to describe how some Brooklyn ministers were using Sarah Smiley’s star power to help attract the unchurched to services:

A recent exhibit of the condition of the churches in New York showed that the seating capacity was less than three hundred thousand. This leaves a population of seven hundred thousand unchurched; or, taking into account young children and invalids who cannot attend religious services, at least a third of a million of people in the city could not be accommodated with church sittings if they desired them. The larger proportion of these is, undoubtedly, of the poorer classes. With them, however, it is rather indifference than want of church accommodations that prevents their hearing the Gospel preached unto them.

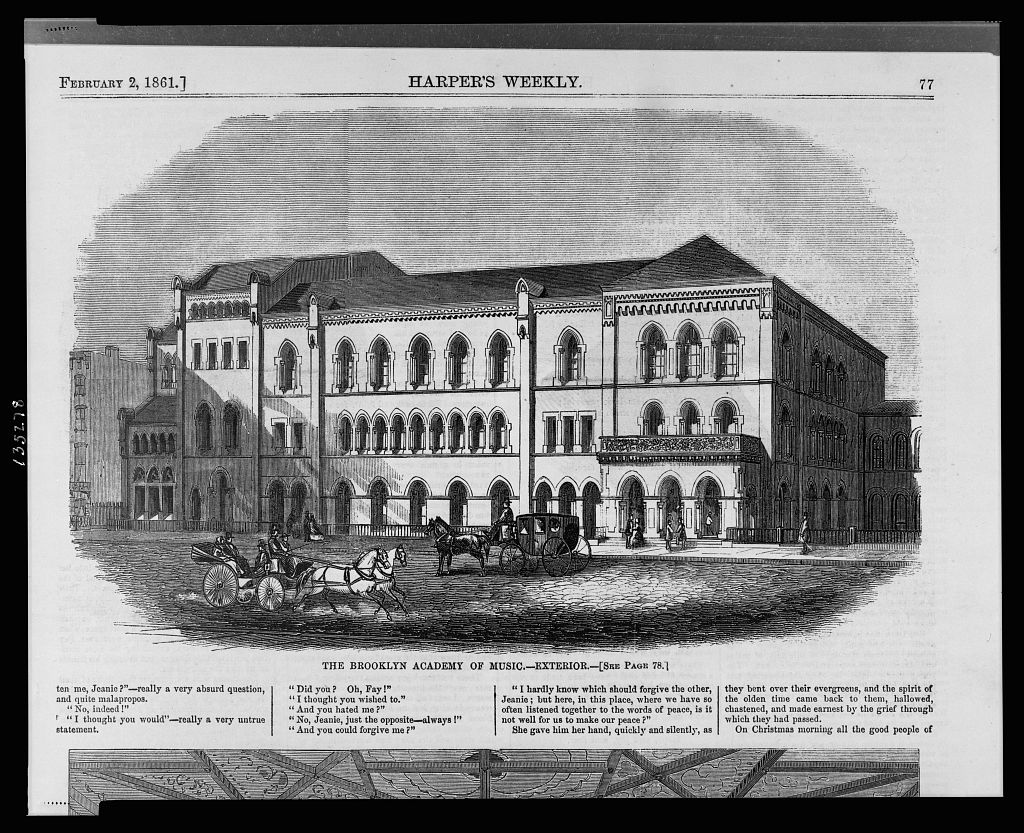

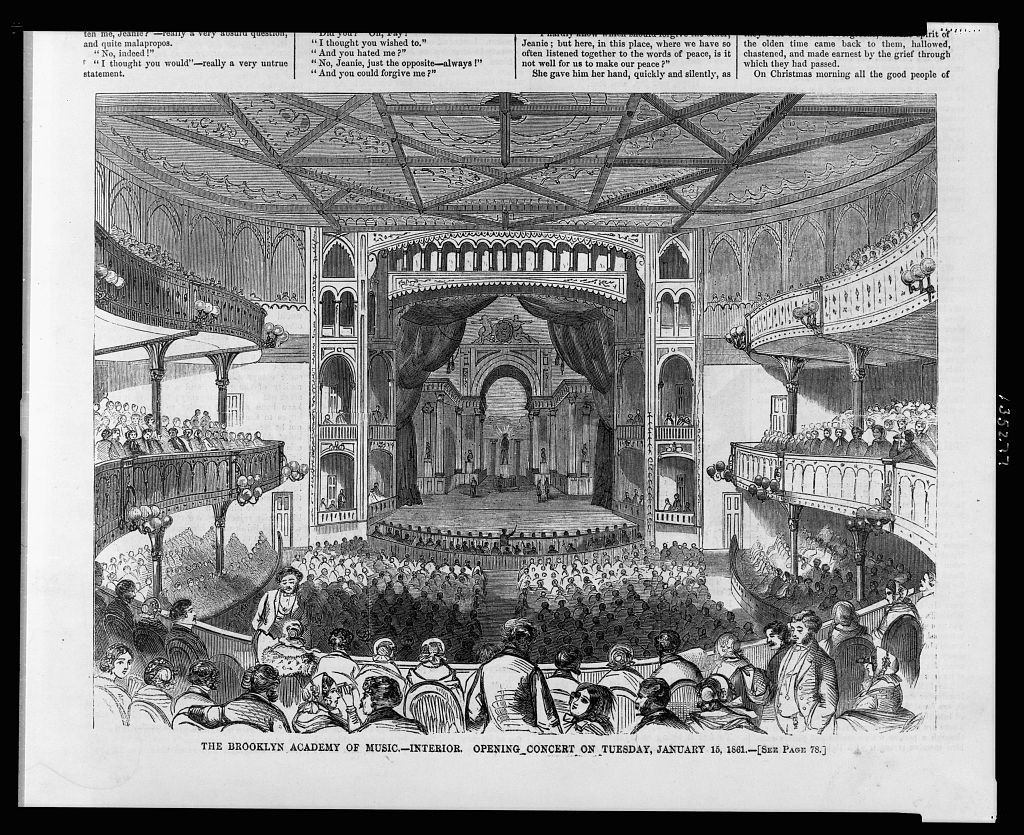

How to get down the drag net so as to gather in the people who don’t care to go to church has been the interesting problem of some of our local evangelists. Services in theatres have oftentimes before attracted the indifferent class, and many, doubtless, who came to be amused remained to pray. A number of Brooklyn ministers hit upon a plan for alluring the outsiders to religious services, and last Sunday night it we it went into successlul operation. The elegant Academy of Music in that city has been engaged for a series of Sunday evenings at a cost of one hundred dollars per night, the expenses being defrayed by subscription. Posters were put up all over the city announcing the programme of entertainments for the evening. “Seats free and no collection taken up.”The star name was that of Miss Smiley, the Quakeress preacher, whose appearance in Dr. Cuyler’s pulpit has caused that gentleman so much bother. Madame Varian Hoffman, the celebrated singer, was announced for solos, assisted by a first-class choir. Mr. Gallaher, the most sensational of the Baptist ministers, (who draws equal to Beecher,) and Dr. Powers, a powerful Congregational preacher, were also promised.

The consequence was that never since the Academy of Music was built had such a multitude filled it. Not only was every seat occupied, but every inch of standing room in the auditorium, even up to the roof. The stage in rear of the speakers and singers was packed with human beings, who stood during the service. The orchestra was full and so were the stage boxes. The doors had to be closed a quarter of an hour before services began, as no more people could get in with safety to the building, and even some of the choristers were unable to penetrate through the mass. The services were a decided success, and when Miss Smiley concluded her earnest appeal, so strong is habit, there was a round of applause in the gallery. Dr. Powers, who conducted the proceedings, announced as stars for the forthcoming evenings Rev. Dr. Chapin and Rev. Mr. Hepworth. One of the secular papers irreverently called this “sugar¬coated religion,” but what matter so long as the class for which it is intended are induced to accept it?

NYM