From the March 18, 1871 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

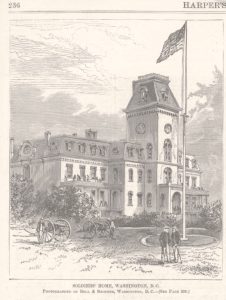

THE SOLDIERS’ HOME.

ON one of the most beautiful sites in the neighborhood of Washington stands an edifice of singular attractiveness, known as “The Soldiers’ Home,” of which we give a sketch on page 236. For this excellent institution the country is largely indebted to the foresight of General WINFIELD SCOTT, who urged its foundation upon the government. The Home, our readers will remember, was the chosen summer residence of President LINCOLN, whose patriotic sense of duty would not permit him to seek, at more distant places of resort, relaxation from the arduous labors and responsibilities of his position during the continuance of the war.

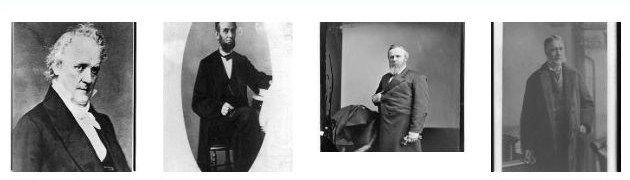

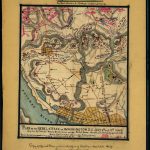

According to the National Park Service “General Winfield Scott designated part of the money Mexico City paid to avoid invasion during the Mexican War” for a military asylum. From 1851-1857 veteran soldiers resided in the original home on the estate. The old soldiers moved into a new, larger building in 1857. That freed up the original “cottage” for presidential use. Abraham Lincoln and his family lived at the old home from July-November in 1862-1864. The residence was sort of an anti-retreat for four days in July 1864 when Jubal Early’s Confederate army threatened the United States capital. While most of the presidential household returned to the White House, Mr. Lincoln stayed in the soldiers home and even came under hostile fire while observing the Battle of Fort Stevens, about a mile from the summer residence. In addition to Lincoln, Presidents Buchanan, Hayes, and Arthur made the home a temporary escape.

According to General Marcus J. Wright (at Project Gutenberg), Winfield Scott sent the War Department $100,000 from Mexico for the veterans’ home:

As an army commander General Scott had frequent occasion to use money for which vouchers or even ordinary receipts could not be taken and the nature of the service could not be specified; he styled them “secret disbursements.” In a letter to the War Department of February 6, 1848, he stated that he “had made no report of such disbursements since leaving Jalapa, (1) because of the uncertainty of our communications with Vera Cruz, and (2) the necessity of certain explanations which, on account of others, ought not to be reduced to writing,” and added, “I have never tempted the honor or patriotism of any man, but have held it as lawful in morals as in war to purchase valuable information or services voluntarily tendered me.”

He charged himself with the money he received in Washington for “secret disbursements,” the one hundred and fifty thousand dollars levied upon the City of Mexico for the immediate benefit of the army, and of the captured tobacco taken from the Mexican Government, with other small sums, all of which were accounted for. He then charged himself with sixty-three thousand seven hundred and forty-five dollars and fifty-seven cents expended in the purchase of blankets and shoes distributed gratuitously to enlisted men, for ten thousand dollars extra supplies for the hospitals, ten dollars each to every crippled man discharged or furloughed, some sixty thousand dollars for secret services, including the native spy company of Dominguez, whose pay commenced in July, and which he did not wish to bring into account with the Treasury. There remained a balance of one hundred thousand dollars, a draft for which he inclosed, saying: “I hope you will allow the draft to go to the credit of the army asylum, and make the subject known in the way you may deem best to the military committees of Congress. The sum is, in small part, the price of American blood so gallantly shed in this vicinity; and considering that the army receives no prize money, I repeat the hope that its proposed destination may be approved and carried into effect…. The remainder of the money in my hands, as well as that expended, I shall be ready to account for at the proper time and in the proper manner, merely offering this imperfect report to explain, in the meantime, the character of the one hundred thousand dollars draft.”

Some sources say Abraham Lincoln’s wife accompanied him to the Battle of Fort Stevens, although I don’t think Mary exposed herself to rebel bullets.

You can find all of Harper’s Weekly for 1871 at HathiTrust. I’m pretty sure the building Harper’s pictured is was the newer structure; the older “cottage” was to the left.

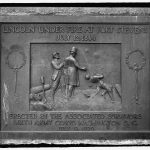

From the Library of Congress: Presidents Buchanan, Lincoln, Hayes, and Arthur; Fort Stevens in 1864; Robert Knox Sneden’s map of Jubal Early’s attack; plaque at the fort; Major General Scott; the Scott Building (1906) with cannon; August 1877 map

, there also are Harewood and Sherman gates; Washington, D.C. area soldiers’ home complex c1863; unveiling Lincoln tablet at Fort Stevens July 12, 1920.

, there also are Harewood and Sherman gates; Washington, D.C. area soldiers’ home complex c1863; unveiling Lincoln tablet at Fort Stevens July 12, 1920.