A duck, a sheep, and a rooster take off in a hot air balloon. … Already heard this one? … No? Well, actually, according to the Château de Versailles, this isn’t a joke. In 1782 the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph and Étienne, began experimenting with using the gas created by a fire to lift a fabric-encased object off the ground. In 1783 Étienne brought the experiments to metro Paris. After a couple tethered attempts, on September 19, 1783, at Verasaille in front of King Louis XVI, the three animals, riding in a basket attached to a balloon, successfully lifted 600 metres off the surface of the earth and traveled about two miles before a rip in the balloon fabric brought the vessel back down to earth. Then, “in front of the Dauphin at Château de La Muette on 21 November, Pilâtre de Rozier became the first man ever to be borne aloft. A new page had been written in the history of mankind.” [1]

Approximately four score and seven years later an American editorial was uncertain whether aerial machines would ever become effective weapons of war. From Harper’s Weekly Supplement January, 21, 1871 page 67:

THE USE OF BALLOONS IN WAR.

AN ingenious Frenchman, M. Bobæuf some time since discovered a method of discharging missiles by means of the gas in the balloon, which he compressed in a special apparatus; and thus, as the weight of the car was diminished by that of the bullet thrown, so also the lifting power of the balloon was lessened by the use of the amount of gas which discharged it.

Such a plan, however, might bring the aeronauts into an unpleasant position; they might fire away all their gas in the action, and find themselves slowly sinking into the hands of their irate enemies below, without any means of taking flight again. On the other hand, the vapor or gas of gunpowder has been used to inflate balloons, apparently not with any great success. What special advantage this gas has over the ordinary coal-gas does not appear.

Such are the only uses to which it has been proposed to apply balloons, as at present constructed, to purposes of war. Numerous other inventions have been proposed; but they are all founded on some plan for obtaining flight, either by guiding a balloon, or by means of an aerial ship, or flying-machine. Of course one of the most obvious uses to which an aerial ship could be put would be to sail quietly into the centre of a town or camp, and attack the unconscious inhabitants. Most of our greatest inventions are now principally useful according as they can be more or less easily adapted to the purposes of war. More thought and trouble have been spent on the Martini-Henry rifle than on the spinning-jenny. Perhaps the culmination of all modern civilization, the greatest achievement of modern science, is the mitrailleuse. Consequently, if ever any attempt to navigate the air can be successful, the first application of the scheme will probably be to purposes of destruction. We shall hear of balloon monitors before we hear of balloon mail, in any other sense than that in which those irregular supplies of letters from Paris are said to come par ballon monté. It is curious – as showing, among other circumstances, how little change there has been in this respect in men’s opinions — that the Jesuit, Francis Lana, who was one of the very earliest to hit upon the idea of any scheme, like that of our balloons, for rising in the air, when he described his machine (which was something like a boat, with several copper globes, from which the air had been exhausted, fastened round her gunwale, in order to raise her into the air) should have looked upon his craft as likely to be of use chiefly in war, and lamented the fact that it would make all castles and strong-holds useless. He, of course, did not know the modern dictum, which has received so much confirmation from recent events, that the easier it is to wage war, and the more destructive war is when waged, the less we of necessity have of it. But then, of course, he only lived in the dark ages, before nineteenth-century civilization and breech-loaders were invented.

Unfortunately all these schemes break down in the flying part. Nobody as yet has managed to fly – at least more than a few yards, which has been accomplished – or to construct any machine capable of being guided in the air. A man can, by the help of a balloon, rise into the air, like a cork in the water, and then drift about at the mercy of the winds, but that is all; and it seems more than probable that he will never do any thing better. To prove the impossibility of such a thing is, indeed, not easy, as it never is to prove any impossibility; but there are a few obstacles in the way which seem almost insuperable.

In order to guide any machine through the air it is necessary that it should have some motion independent of that given it by the wind– some steerage-way, at all events. It is obvious that a boat simply drifting before a current can not be steered; the rudder in such a case is simply useless, and is only available when the boat has a definite motion in some particular direction independent of that given it by the stream. Some motion, then, independent of the wind, the balloon must have. Again, to be of any avail beyond checking its forward movement, such power must be capable of driving the balloon faster than the wind, or else it can only be of use in perfectly calm weather. Considering the amount of force required to move a body along the ground, with the leverage afforded by the solid earth, at a pace equal to that even of a light breeze, the power required to move any object in the air, with no better leverage than that given by the air itself, may easily be imagined. Suppose that an aerial ship could be made which would go twenty miles an hour in a perfect calm, that would be considered a sufficient feat; but in a breeze which moved at the rate of twenty miles an hour it could only be stationary, or, at most, move in a direction with the wind, but not exactly before it–with the wind on her quarter, to use a nautical expression. It is to be remembered that a balloon must of necessity be carried along entirely by the wind, so that, as regards the balloon, the wind has absolutely no relative motion. Aeronauts never feel any breeze whatever in a balloon, since it and the wind travel along precisely at the same pace. Hence it can not sail, as a boat does, in a direction at an acute angle to that of the wind, any more than a boat can drift in any direction but that of the current. The motion of the boat is the result of two forces acting upon it; the balloon is subjected only to one. The first thing needful, then, is to impart motion to the vessel which is to sail “with sublime dominion through the azure fields of air.” Until this can be done it is hopeless to think of directing it.

This puts balloons out of the question. It will probably never be possible to make a balloon which can lift any engine capable of moving it. The surface of a balloon is enormous; and to drive such a large mass–which is incapable, from its nature, of receiving momentum–through the air, would require an engine of immense power, and, therefore, of considerable weight. The only way of increasing the lifting power of a balloon is by increasing its size, and consequently its surface, and consequently, again, the power of its engine. This is a hopeless dilemma. Then a silk balloon is not strong enough to resist any pressure from the air; and no other material of equal lightness and sufficient strength is likely to be discovered. Any frame-work which would serve to strengthen the balloon, and enable it to keep its shape, would also be heavy. Lastly, the guiding machinery must be attached to the balloon itself, not to the car–so that the ordinary shape could not be employed; and the machine would have to be fish or boat shaped–an almost impossible form for a gas balloon.

If, then, we are ever to rival the birds, it must be by aid of some mechanical means–some flying-machine. Numbers of these have been invented, but it hardly necessary to say that none of them have as yet been successful. No one has yet really discovered the principles on which birds fly, or on which it will be necessary to proceed before men can do the same. Any of these machines would doubtless, if successful, be very useful for purposes of fighting, but some few have been intended by their inventors chiefly for that object.Among the most remarkable of these is one for which a patent was taken out, in 1855, by the Earl of Aldborough. This invention, if it could be brought to work, would of itself be quite sufficient to revolutionize the whole art of warfare; and balloons would by this time have taken the place of men-of-war, with the additional advantage of being equally useful over land and sea, which no ship could possibly be. Then the present war might have seen fulfilled the prediction of the poet of “Locksley Hall,” who, in fancy,

“Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rain’d a ghastly dew

From the nations’ airy navies grappling in the central blue;

Far along the world-wide whisper of the south wind rushing warm,

With the standards of the people plunging through the thunder-storm.”

The specification of the patent in question describes a perfect armament of aerial vessels of warlike nature, which probably never existed even as models. Each of them is a sort of balloon, fitted with wings to be worked by hand and by a complicated arrangements of springs. Some are of the ordinary balloon shape, and have wings fastened to the car; others are in the shape of a boat. They are all to be raised by means of gas, and the wings are to be used only to impart horizontal motion and direction. How liable these machines are to all the objections mentioned above is obvious.

The armament of these vessels is complete. Guns and muskets are to be so placed as to utilize the recoil–how, is not said–while explosive shells are to be dropped from them. Some are even to be thinly armor-plated at top, that they may be safely protected from the attack of hostile vessels above. To each ship one or more “pilot-boats” are attached, for the purpose of guiding, landing passengers, etc., so that no convenience may be wanted.

To ensure the safety of these marvelous ships a fortress is to be provided, guarded by a sort of chevaux de frise, arranged like the entrance to a mouse-trap, so as to allow vessels to go out, but impede the entry of any hostile ships. In order to admit friendly balloons the stakes of the chevaux de frise are moveable.

The invention is apparently the most complete in intention of any which would apply balloons to fighting uses. How utterly impracticable it is in all its execution is obvious. One or two others of like character have been patented, but one such is enough to mention–ex uno disce omnes. Still it is easy to laugh at the attempt after aerostation. The science may, after all, but be in its infancy; and some new source of motive power may yet be discovered which may lift us through the air. Till such discovery we must be content to go on destroying one another with the means we have–means, to judge of the present war, of very sufficient power.

Balloons weren’t used as weapons during the American Civil War, but they did have a military purpose. According to the American Battlefield Trust both the Confederacy and the Union experimented with using balloons for aerial reconnaissance, but The Union effort was more organized. Its Union Army Balloon Corps operated from 1861-1863 under the direction of Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. John LaMountain also reconnoitered in the air, mostly for General Benjamin F. Butler around Fort Monroe; he didn’t get along too well with Professor Lowe and was discharged in February 1862.

You can read about Thaddeus Lowe’s June 16, 1861 test ascent from where the National Air and Space Museum now stands at the Smithsonian. With the balloon tethered at 500 feet Professor Lowe, along with “telegrapher Herbert Robinson and George Burns, supervisor of the telegraph company,” sent President Lincoln what is said to be the first telegraph from the air.

According to Wikipedia, in “Locksley Hall” (published in 1842) Alfred Tennyson predicted “the rise of both civil aviation and military aviation in the following words:

Saw the heavens fill with commerce, argosies of magic sails,

Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales;

Heard the heavens fill with shouting, and there rain’d a ghastly dew

From the nations’ airy navies grappling in the central blue;

Of course, by World War I flying machines were widely used as weapons. Airplanes were in the ascendancy, but the gas-filled zeppelins bombed Britain. The zeppelin’s creator, Ferdinand von Zeppelin was in the United States during the Civil War:

Ferdinand von Zeppelin served as an official observer with the Union Army during the American Civil War. During the Peninsular Campaign, he visited the balloon camp of Thaddeus S. C. Lowe shortly after Lowe’s services were terminated by the Army. Von Zeppelin then travelled to St. Paul, MN where the German-born former Army balloonist John Steiner offered tethered flights. His first ascent in a balloon, made at Saint Paul, Minnesota during this visit, is said to have been the inspiration of his later interest in aeronautics.

Zeppelin’s ideas for large airships were first expressed in a diary entry dated 25 March 1874. Inspired by a recent lecture given by Heinrich von Stephan on the subject of “World Postal Services and Air Travel”, he outlined the basic principle of his later craft: a large rigidly-framed outer envelope containing a number of separate gasbags.

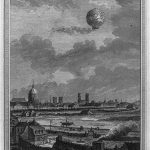

According to Wikipedia Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier took the first manned untethered balloon flight on the outskirts of Paris along with François Laurent d’Arlandes. Benjamin Franklin backs up the online encyclopedia’s statement that there were two aeronauts on the November 21st flight. He was serving as United States to France in 1783. At Project Gutenberg you can read the 1907 Benjamin Franklin and the First Balloons edited by Abbott Lawrence Rotch. This publication contains a series of letters from Mr. Franklin to Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society of London describing the balloon experiments from a tethered hydrogen-filled balloon ascent on August 27th, then the hot-air journeys on September 19 and November 21, through the first manned hydrogen balloon trip on December 1st. Benjamin Franklin might have been off by a day, but he does mention he visited with one of the two first hot-air aeronauts on November 21st: “One of these courageous Philosophers, the Marquis d’Arlandes, did me the honour to call upon me in the Evening after the Experiment, with Mr. Montgolfier the very ingenious Inventor. I was happy to see him safe. He informed me that they lit gently without the least Shock, and the Balloon was very little damaged.” He mentioned the reconnaissance possibilities: “This Method of filling the Balloon with hot Air is cheap and expeditious, and it is supposed may be sufficient for certain purposes, such as elevating an Engineer to take a View of an Enemy’s Army, Works, &c. conveying Intelligence into, or out of a besieged Town, giving Signals to distant Places, or the like.” And also philosophised: “This Experience is by no means a trifling one. It may be attended with important Consequences that no one can foresee. We should not suffer Pride to prevent our progress in Science. Beings of a Rank and Nature far superior to ours have not disdained to amuse themselves with making and launching Balloons, otherwise we should never have enjoyed the Light of those glorious objects that rule our Day & Night, nor have had the Pleasure of riding round the Sun ourselves upon the Balloon we now inhabit.”

While the first manned hot air balloon flight occurred on November 21, 1783, the first manned hydrogen balloon flight took place on December 1, 1783. The hydrogen balloon also took off from Paris, and Benjamin Franklin also described that feat in a letter to Joseph Banks. This balloon was built by the Robert brothers. The aeronauts were one of the brothers and Jacques Charles

According to Wikipedia war helped inspire the first hot air balloons: “Of the two brothers, it was Joseph who was first interested in aeronautics; as early as 1775 he built parachutes, and once jumped from the family house. He first contemplated building machines when he observed laundry drying over a fire incidentally form pockets that billowed upwards. Joseph made his first definitive experiments in November 1782 while living in Avignon. He reported some years later that he was watching a fire one evening while contemplating one of the great military issues of the day—an assault on the fortress of Gibraltar, which had proved impregnable from both sea and land. Joseph mused on the possibility of an air assault using troops lifted by the same force that was lifting the embers from the fire. He believed that the smoke itself was the buoyant part and contained within it a special gas, which he called “Montgolfier Gas”, with a special property he called levity, which is why he preferred smoldering fuel.”

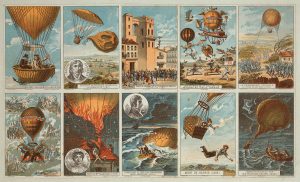

Balloons were used for military reconnaissance at least by the 1794 Battle of Fleurus: “The French use of the reconnaissance balloon l’Entreprenant was the first military use of an aircraft that influenced the result of a battle.”

The French used balloons during the September 1870 – January 1871 Siege of Paris as part of two-way communication with the outside world. Balloons got information out of Paris; carrier pigeons brought messages back in. From Balloons, Airships, and Flying Machines by Gertrude Bacon (1905) (at Project Gutenberg (pages 73-78)):

But the time when the balloon was most largely and most usefully used in time of war was during the Siege of Paris. In the month of September 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, Paris was closely invested by the Prussian forces, and for eighteen long weeks lay besieged and cut off from all the rest of the world. No communication with the city was possible either by road, river, rail, or telegraph, nor could the inhabitants convey tidings of their plight save by one means alone. Only the passage of the air was open to them.

Quite at the beginning of the siege it occurred to the Parisians that they might use balloons to escape from the beleaguered town, and pass over the heads of the enemy to safety beyond; and inquiry was at once made to discover what aeronautical resources were at their command.

It was soon found that with only one or two exceptions the balloons actually in existence within the walls were unserviceable or unsuitable for the work on hand, being mostly old ones which had been laid aside as worthless. One lucky discovery was, however, made. Two professional aeronauts, of well-proved experience and skill, were in Paris at the time. These were MM. Godard and Yon, both of whom had been in London only a short time before in connection with a huge captive balloon which was then being exhibited there. They at once received orders to establish two balloon factories, and begin making a large number of balloons as quickly as possible. For their workshops they were given the use of two great railway stations, then standing idle and deserted. No better places for the purpose could be imagined, for under the great glass roofs there was plenty of space, and the work went on apace.

As the balloons were intended to make only one journey each, plain white or coloured calico (of which there was plenty in the city), covered with quick-drying varnish, was considered good enough for their material. Hundreds of men and women were employed at the two factories; and altogether some sixty balloons were turned out during the siege. Their management was entrusted to sailors, who, of all men, seemed most fitted for the work. The only previous training that could be given them was to sling them up to the roof of the railway stations in a balloon car, and there make them go through the actions of throwing out ballast, dropping the anchor, and pulling the valve-line. This was, of course, very like learning to swim on dry land; nevertheless, these amateurs made, on the whole, very fair aeronauts.

But before the first of the new balloons was ready experiments were already being made with the few old balloons then in Paris. Two were moored captive at different ends of the town to act as observation stations from whence the enemy’s movements could be watched. Captive ascents were made in them every few hours. Meanwhile M. Duruof, a professional aeronaut, made his escape from the city in an old and unskyworthy balloon called “Le Neptune,” descending safely outside the enemy’s lines, while another equally successful voyage was made with two small balloons fastened together.

And then, as soon as the possibility of leaving Paris by this means was fully proved, an important new development arose. So far, as was shown, tidings of the besieged city could be conveyed to the outside world; but how was news from without to reach those imprisoned within? The problem was presently solved in a most ingenious way.

There was in Paris, when the siege commenced, a society or club of pigeon-fanciers who were specially interested in the breeding and training of “carrier” or “homing” pigeons. The leaders of this club now came forward and suggested to the authorities that, with the aid of the balloons, their birds might be turned to practical account as letter-carriers. The idea was at once taken up, and henceforward every balloon that sailed out of Paris contained not only letters and despatches, but also a number of properly trained pigeons, which, when liberated, would find their way back to their homes within the walls of the besieged city.

When the pigeons had been safely brought out of Paris, and fallen into friendly hands beyond the Prussian forces, there were attached to the tail feathers of each of them goose quills, about two inches long, fastened on by a silken thread or thin wire. Inside these were tiny scraps of photographic film, not much larger than postage stamps, upon which a large number of messages had been photographed by microscopic photography. So skilfully was this done that each scrap of film could contain 2500 messages of twenty words each. A bird might easily carry a dozen of these films, for the weight was always less than one gramme, or 15½ grains. One bird, in fact, arrived in Paris on the 3rd of February carrying eighteen films, containing altogether 40,000 messages. To avoid accidents, several copies of the same film were made, and attached to different birds. When any of the pigeons arrived in Paris their despatches were enlarged and thrown on a screen by a magic-lantern, then copied and sent to those for whom they were intended.

This system of balloon and pigeon post went on during the whole siege. Between sixty and seventy balloons left the city, carrying altogether nearly 200 people, and two and a half million letters, weighing in all about ten tons. The greater number of these arrived in safety, while the return journeys, accomplished by the birds, were scarcely less successful. The weather was very unfavourable during most of the time, and cold and fogs prevented many pigeons from making their way back to Paris. Of 360 birds brought safely out of the city by balloon only about 60 returned, but these had carried between them some 100,000 messages.

Of the balloons themselves two, each with its luckless aeronaut, were blown out to sea and never heard of more. Two sailed into Germany and were captured by the enemy, three more came down too soon and fell into the hands of the besieging army near Paris, and one did not even get as far as the Prussian lines. Others experienced accidents and rough landings in which their passengers were more or less injured. Moreover, each balloon which sailed by day from the city became at once a mark for the enemy’s fire; so much so that before long it became necessary to make all the ascents by night, under cover of darkness.

They were brave men indeed who dared face the perils of a night voyage in an untried balloon, manned by an unskilled pilot, and exposed to the fire of the enemy, into whose hands they ran the greatest risk of falling. It is small wonder there was much excitement in Paris when it became known that the first of the new balloons made during the siege was to take away no less a personage than M. Gambetta, the great statesman, who was at the time, and for long after, the leading man in France. He made his escape by balloon on the 7th of October, accompanied by his secretary and an aeronaut, and managed to reach a safe haven, though not before they had been vigorously fired at by shot and shell, and M. Gambetta himself had actually been grazed on the hand by a bullet.

Animals have helped humans explore space; Wikipedia sees the three balloon animals as precursor: “Animals had been used in aeronautic exploration since 1783 when the Montgolfier brothers sent a sheep, a duck, and a rooster aloft in a hot air balloon to see if ground-dwelling animals can survive (the duck serving as the experimental control).”

The material from Harper’s Weekly 1870 comes from the Internet Archive (on page 701 M. Gambetta is identified as one of the passengers escaping over the Prussian lines); you can read the editorial and all of the other 1871 Harper’s Weekly content at Hathi Trust.

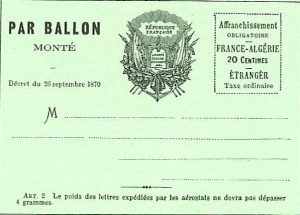

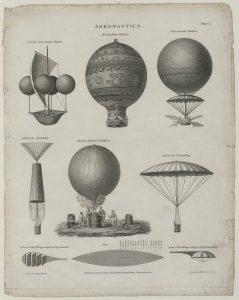

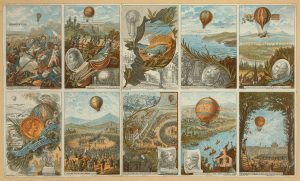

From Wikimedia Commons: ChrisO’s 2004 photograph of a Reffye mitrailleuse at Les Invalides, Paris – the photo is licensed under Creative Commons; balloon air mail postcard – the manned balloon mail helped Paris communicate with the outside world during the Prussian siege of September 1870-January 1871; November 21, 1873 flight in a colorful Montgolfier balloon – it’s from one of the collecting sets at the Library of Congress; Bargès photo of the statue of the Montgolfier brothers in Annonay by Henri Louis Cordier (1853–1925) is licensed under Creative Commons; the Bataille de Fleurus 1794

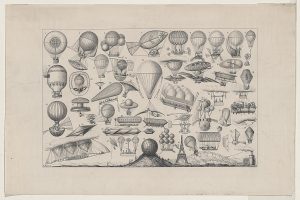

From the Library of Congress: showing first balloon flight on September 19, 1783 with a sheep, a duck and a rooster as passengers; aeronautics from 1818 – the Montgolfiers’ balloon next to Father Lana’s floating boat; flying machines with some form of propulsion between 1885 and 1904; collecting card, left and right, the one on the right includes a representation of the use of a reconnaissance balloon at the 1794 Battle of Fleurus; John LaMountain reconnoitering near Fort Monroe from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper August 31,1861; balloon camp at Gaines’ Mill; Count von Zeppelin with Union officers Fairfax Court House June 1863 – a well-read group, apparently enjoying Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, ; a Capitol visit, said to be by the Graf Zeppelin (1928-37); hot air flight on November 21, 1783; the first manned hydrogen balloon lift-off December 1, 1783; a surprise in the sky December 1, 1783; the first manned hydrogen balloon landing on December 1, 1783; the mitrailleuse mounted on a French airplane from the July 15, 1917 issue of the New York Tribune;

The image of the aircraft-carrying barge comes from the Naval History and Heritage Command: “Balloon Reconnaissance after Launch from the USS GEORGE WASHINGTON PARKE CUSTIS, Civil War Naval Aircraft Carrier, a Balloon ascends over the Potomac River, making reconnaissance of blockade, November 1861, near Budd’s Ferry below Mount Vernon. Drawing in Lowe Collection at National Archives.” George Washington Parke Custis‘s father was George Washington’s step-son; his daughter married Robert E. Lee.

- [1]According to several sources, including Benjamin Franklin, it was a two-man crew that ascended on November 21st↩