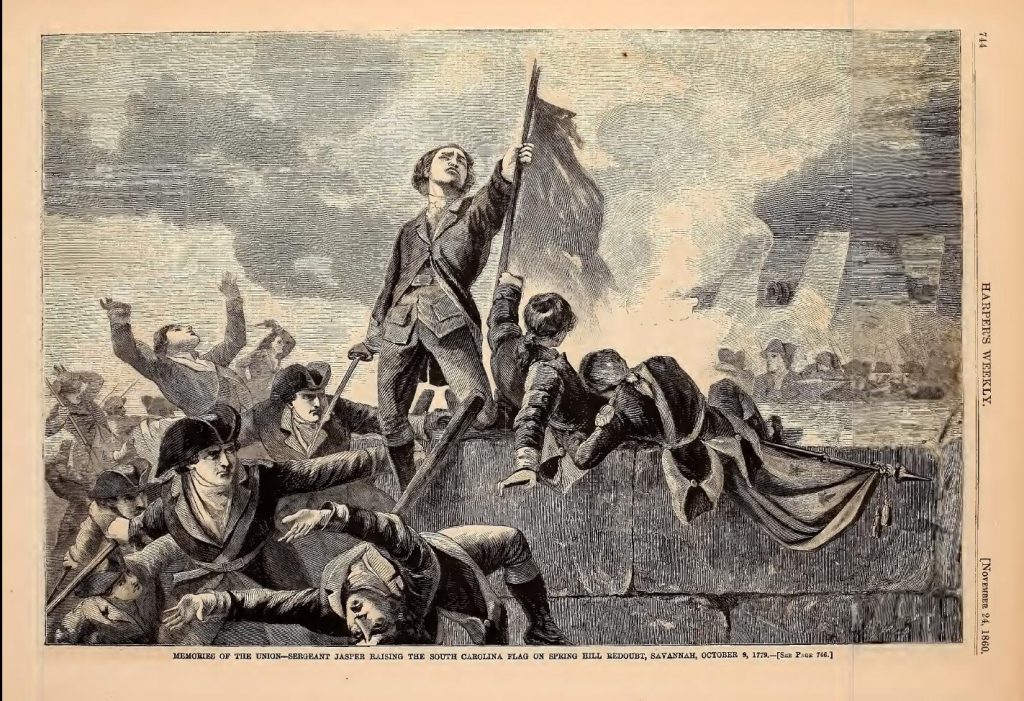

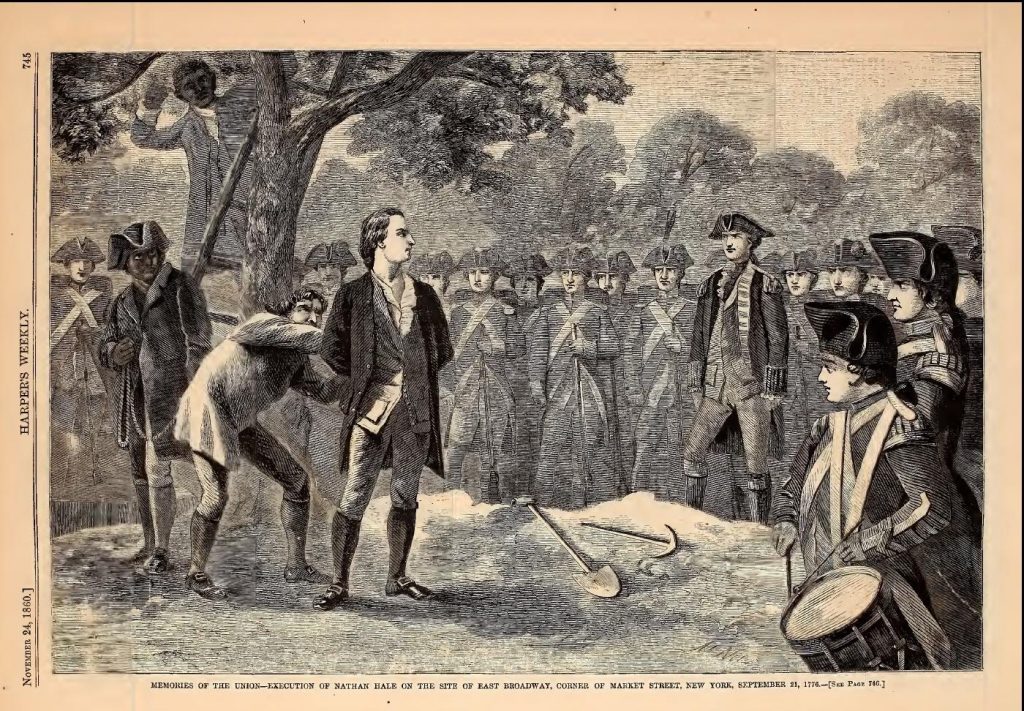

The day before the 1860 U.S. presidential election the governor of South Carolina advised secession in the event of Abraham Lincoln’s probable victory. Thanks to the telegraph, that news got up North very quickly. On Election Day, November 6, 1860, The New-York Times headlined “Immediate Secession Recommended by the Governor of South Carolina,” and included letters from Virginia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi assessing disunion sentiment. With Mr. Lincoln’s election, another New York City publication, Harper’s Weekly, seemed to anticipate disunion by providing images of Charleston, South Carolina; “memories of the Union;” Savannah, Georgia; the defenses of the City of New York; Washington, D.C. (“in view of the momentous discussions which are now going on at the Federal Capital”).

_______

As southern states decided if they would secede from the Union, a dispute reportedly broke out at a public meeting in Boston about whether the anniversary of violent abolitionist John Brown’s execution should be publicly commemorated. Some people at the meeting were concerned about offending Virginia, a populous slave state that, unlike the deep South, gave its 1860 Electoral College votes to John Bell and the Constitutional Union Party, not John Breckinridge of the breakaway southern Democrats.

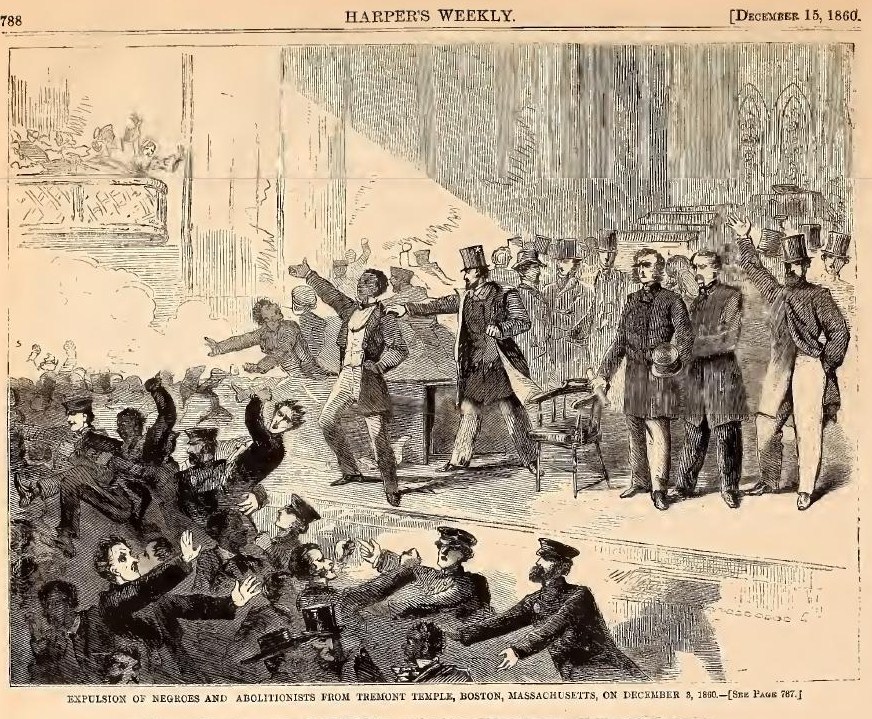

From the December 15, 1860 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

AFFRAY IN BOSTON.

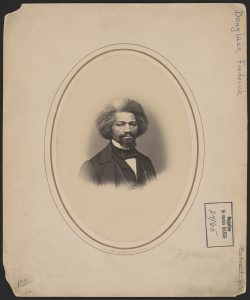

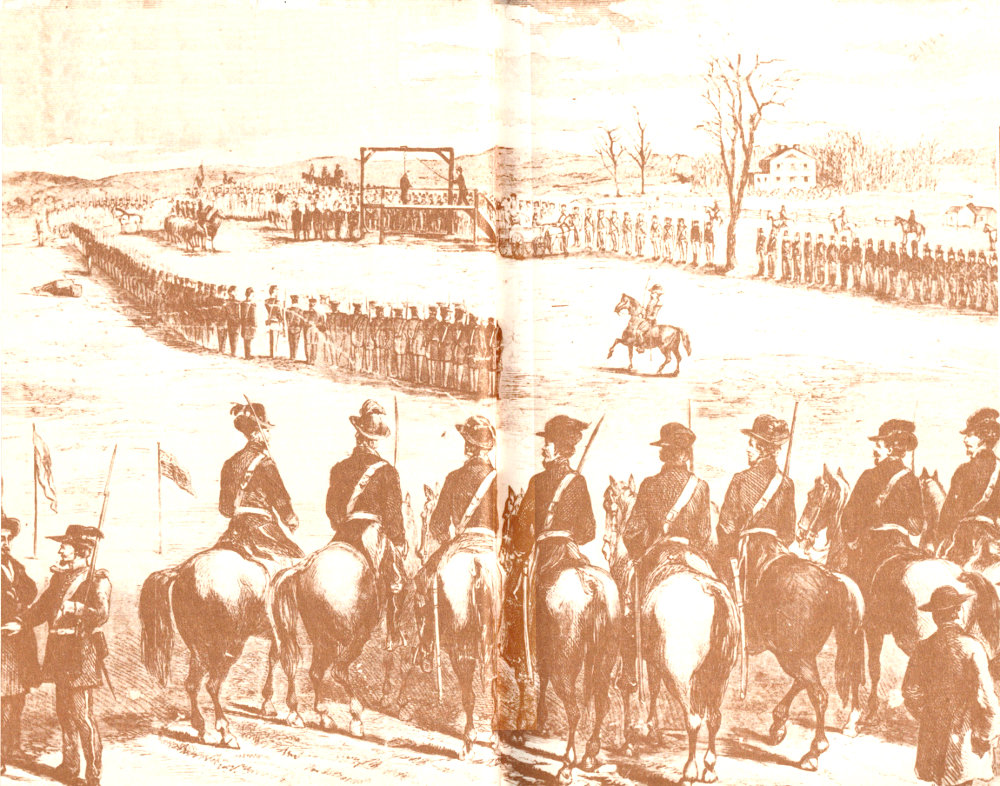

WE publish on page 788, from a sketch by a person who was present, a picture of the riot which took place on December 3, in Tremont Temple, Boston, on the occasion of the attempt of Garrison, Redpath, Sanborn, Douglass, and other abolitionists to celebrate the anniversary of the execution of John Brown. No sooner had the abolitionists appeared in the hall than a number of citizens of Boston proceeded to organize the meeting. This was resisted by the abolitionists and a scuffle ensued; but the Union men carried their point, and organized the meeting by electing Mr. Fay chairman. A calm speech was delivered by Mr. Fay, in spite of frequent interruptions by Fred Douglass, and the following resolutions were put up and carried:

“Whereas, That it is fitting upon the occasion of the anniversary of the execution of John Brown, for his piratical and bloody attempt to create an insurrection among the slaves of the State of Virginia, for the people of this Commonwealth to assemble, and express their horror of the man and of the principles which led to the foray; therefore it is

“Resolved, 1. That no virtuous and law-abiding citizen of this Commonwealth ought to countenance, sympathize, or hold communion with, any man who believes that John Brown and his aiders and abettors in that nefarious enterprise were right in any sense of that word.

“2. That the present perilous juncture in our political affairs, in which our existence as a nation is imperiled, requires of every citizen who loves his country to come forward and to express his sense of the value of the Union, alike important to the free labor of the North, the slave labor of the South, and to the interests of commerce, manufactures, and agriculture of the world.

“3. That we tender to our brethern in Virginia our warmest thanks for the conservative spirit they have manifested, notwithstanding the unprovoked and lawless attack made upon them by John Brown and his associates, acting if not with the connivance, at least with the sympathy of a few fanatics of the Northern States, and that we hope they will still continue to aid in opposing the fanaticism which is even now attempting to subvert the Constitution and the Union.

“4. That the people of this city have submitted too long in allowing irresponsible individuals and political demagogues of every description to hold public meetings to disturb the public peace and misrepresent us abroad. They have become a nuisance, which in self-defense we are determined shall henceforward be summarily abated.

“4. [sic] That a copy of these resolutions be sent to each of the persons named in the coll[?] for this meeting.”

After the passage of the resolutions, speeches were made by Fred Douglass and others, and the meeting ended in the expulsion from the hall of the abolitionists and negroes by sheer force.

According to the December 4, 1860 issue of The New-York Times, the public was invited to the programmes to celebrate John Brown’s death. Apparently a lot of the public that showed up were against the abolitionist celebration; they tried to take over the meeting. Things got out of hand and eventually the police “cleared the hall and locked the doors.” The abolitionists changed venues:

After the Chairman had pronounced the meeting dissolved, FRED. DOUGLASS, SANBORN and a few others, manifested some resistance to the police, and were ejected from the platform and hall. During the uproar Rev. J. STELLA MARTIN announced that a meeting would be held in his church in the evening. In response to this announcement the Baptist Church (colored) in Joy-street, was filled at an early hour. The edifice was small, end a large proportion of the audience were black. Here WENDELL PHILLIPS, JOHN BROWN, Jr., FRED. DOUGLASS and other leading John Brown sympathizers ventilated their opinions freely, with little interruption. A woman named CHAPMAN appeared to preside. Several policemen were stationed in the Church. Outside there was an immense crowd, and a strong force of police. The disturbance was confined to noisy demonstrations, though the crowd seemed very anxious to get hold of REDPATH.

The meeting broke up at about 10 o’clock, and the audience dispersed quietly. Some of the leading spirits were hooted at in passing through the outside crowd, but no violence was committed.

FRANK. B. SANBORN was acting President of the meeting. In anticipation of a possible riot, the Second Battalion of Infantry was held in readiness at their Armory by order of the Mayor. The Police force however was amply sufficient, and the day and evening passed simply with a good-natured, but quite patriotic excitement.

The Richmond Daily Dispatch covered the Tremont meeting in it’s December 3, 1860 issue. On November 27th the newspaper published a letter from Pennsylvania governor William F. Packer to the meeting organizers:

ABOLITIONISM REBUKED.

–A letter having been addressed by James Redpath to Gov. Packer , of Pennsylvania, inviting him to participate in a meeting at Tremont Temple, in Boston, on the anniversary of the execution of John Brown , Governor P. promptly returned the invitation with the subjoined reply written on a blank page of Mr. Redpath’s letter:

LETTER

Executive Department, Harrisburg, Pa., Nov, 21, 1860. Sir:

–In my opinion, the young men whose names are attached to the foregoing letter would better serve God and their country by attending to their own business. John Brown was rightfully hanged. and his life should be a warning to others having similar proc [sic]

Wm. F. Packer , Governor of Pennsylvania.

In his account of the tumultuous meeting, William S. McFeely writes that the unionists who took over the Tremont gathering were supporters of the Constitutional Union party. Frederick Douglass was the main antagonist to the unionists and it was only after he was first ejected from the hall by the police that the unionists passed the resolutions. He then came back by another door and continued the argument until the police again removed the abolitionists. During the night meeting at J. Sella Martin’s church, Mr. Douglass “advocated a course of action even more subversive than John Brown’s insurrection: ‘We must … reach the slaveholder’s conscience through his fear of personal danger. We must make him feel that there is death in the air around him, that there is death in the pot before him, that thee is death all around him.’ … he called for encouraging more slaves to run away, and revived the old dream that the Appalachian mountains could become a haven for them. ‘I believe in agitation,’ … with uncharacteristic bitterness, he declared, ‘The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter, is to make a few dead slave catchers.'” Mr. Douglass included war as one of the methods to end slavery.[1]

Frederick Douglass alluded to Massachusetts and New England in a May 30, 1881 address about John Brown at Storer College in Harper’s Ferry:

… The difficulty in doing justice to the life and character of such a man is not altogether due to the quality of the zeal, or of the ability brought to the work, nor yet to any imperfections in the qualities of the man himself; the state of the moral atmosphere about us has much to do with it. The fault is not in our eyes, nor yet in the object, if under a murky sky we fail to discover the object. Wonderfully tenacious is the taint of a great wrong. The evil, as well as “the good that men do, lives after them.” Slavery is indeed gone; but its long, black shadow yet falls broad and large over the face of the whole country. It is the old truth oft repeated, and never more fitly than now, “a prophet is without honor in his own country and among his own people.” Though more than twenty years have rolled between us and the Harper’s Ferry raid, though since then the armies of the nation have found it necessary to do on a large scale what John Brown attempted to do on a small one, and the great captain who fought his way through slavery has filled with honor the Presidential chair, we yet stand too near the days of slavery, and the life and times of John Brown, to see clearly the true martyr and hero that he was and rightly to estimate the value of the man and his works. Like the great and good of all ages—the men born in advance of their times, the men whose bleeding footprints attest the immense cost of reform, and show us the long and dreary spaces, between the luminous points in the progress of mankind,—this our noblest American hero must wait the polishing wheels of after-coming centuries to make his glory more manifest, and his worth more generally acknowledged. Such instances are abundant and familiar. If we go back four and twenty centuries, to the stately city of Athens, and search among her architectural splendor and her miracles of art for the Socrates of to-day, and as he stands in history, we shall find ourselves perplexed and disappointed. In Jerusalem Jesus himself was only the “carpenter’s son”—a young man wonderfully destitute of worldly prudence—a pestilent fellow, “inexcusably and perpetually interfering in the world’s business,”—”upsetting the tables of the money-changers”—preaching sedition, opposing the good old religion—”making himself greater than Abraham,” and at the same time “keeping company” with very low people; but behold the change! He was a great miracle-worker, in his day, but time has worked for him a greater miracle than all his miracles, for now his name stands for all that is desirable in government, noble in life, orderly and beautiful in society. That which time has done for other great men of his class, that will time certainly do for John Brown. The brightest gems shine at first with subdued light, and the strongest characters are subject to the same limitations. Under the influence of adverse education and hereditary bias, few things are more difficult than to render impartial justice. Men hold up their hands to Heaven, and swear they will do justice, but what are oaths against prejudice and against inclination! In the face of high-sounding professions and affirmations we know well how hard it is for a Turk to do justice to a Christian, or for a Christian to do justice to a Jew. How hard for an Englishman to do justice to an Irishman, for an Irishman to do justice to an Englishman, harder still for an American tainted by slavery to do justice to the Negro or the Negro’s friends. “John Brown,” said the late Wm. H. Seward, “was justly hanged.” “John Brown,” said the late John A. Andrew, “was right.” It is easy to perceive the sources of these two opposite judgments: the one was the verdict of slave-holding and panic-stricken Virginia, the other was the verdict of the best heart and brain of free old Massachusetts. One was the heated judgment of the passing and passionate hour, and the other was the calm, clear, unimpeachable judgment of the broad, illimitable future.

There is, however, one aspect of the present subject quite worthy of notice, for it makes the hero of Harper’s Ferry in some degree an exception to the general rules to which I have just now adverted. Despite the hold which slavery had at that time on the country, despite the popular prejudice against the Negro, despite the shock which the first alarm occasioned, almost from the first John Brown received a large measure of sympathy and appreciation. New England recognized in him the spirit which brought the pilgrims to Plymouth rock and hailed him as a martyr and saint. True he had broken the law, true he had struck for a despised people, true he had crept upon his foe stealthily, like a wolf upon the fold, and had dealt his blow in the dark whilst his enemy slept, but with all this and more to disturb the moral sense, men discerned in him the greatest and best qualities known to human nature, and pronounced him “good.” Many consented to his death, and then went home and taught their children to sing his praise as one whose “soul is marching on” through the realms of endless bliss. One element in explanation of this somewhat anomalous circumstance will probably be found in the troubled times which immediately succeeded, for “when judgments are abroad in the world, men learn righteousness.” …

You can read his entire speech at Project Gutenberg. The pamphlet’s introduction refers to the Tremont Temple disturbance in 1860:

In substance, this address, now for the first time published, was prepared several years ago, and has been delivered in many parts of the North. Its publication now in pamphlet form is due to its delivery at Harper’s Ferry, W. Va., on Decoration day, 1881, and to the fact that the proceeds from the sale of it are to be used toward the endowment of a John Brown Professorship in Storer College, Harper’s Ferry—an institution mainly devoted to the education of colored youth.

That such an address could be delivered at such a place, at such a time, is strikingly significant, and illustrates the rapid, vast and wonderful changes through which the American people have been passing since 1859. Twenty years ago Frederick Douglass and others were mobbed in the city of Boston, and driven from Tremont Temple for uttering sentiments concerning John Brown similar to those contained in this address. Yet now he goes freely to the very spot where John Brown committed the offense which caused all Virginia to clamor for his life, and without reserve or qualification, commends him as a hero and martyr in the cause of liberty. This incident is rendered all the more significant by the fact that Hon. Andrew Hunter, of Charlestown,—the District Attorney who prosecuted John Brown and secured his execution,—sat on the platform directly behind Mr. Douglass during the delivery of the entire address and at the close of it shook hands with him, and congratulated him, and invited him to Charlestown (where John Brown was hanged), adding that if Robert E. Lee were living, he would give him his hand also.

“The hanging of John Brown took place at 11:30 a.m., December 2, 1859, in a field just outside Charles Town. “

You learn about John Brown’s trial at Professor Douglas O. Linder’s Famous Trials

Abolitionist John Sella Martin was born into slavery in North Carolina. After the American Civil War he moved back South and worked in education and politics.

I didn’t know about American Revolutionary War soldier William Jasper, but that would explain the pseudonym of The New-York Times‘s antebellum correspondent from Charleston.

From Wikimedia Commons: Boston from a hot air balloon on October 13, 1860; temple organ 1881; DASonnenfeld’s 2015 photo of the statue of John Brown and the African-American boy is licensed under Creative Commons (“Larger than lifesize, bronze sculpture of John Brown and African-American youth, by Joseph P. Pollia. Installed at John Brown’s Farm, near Lake Placid, New York, 1935. Commissioned by the John Brown Memorial Association.”) – you can see a picture of the statue on its pedestal at Uncovering New York

From the Library of Congress: the page with the two drawings of Frederick Douglass from a set called “Election posters. Ward 5, Boston. 1860”; Frederick Douglass photograph from 1862; young girl looking at John Brown’s grave – it looks like the other names are Captain John Brown, who died in 1776, and Oliver, who died from wounds received during the Harpers Ferry raid – his remains were returned to the family in 1899; new steamship line

All the 1860 Harper’s Weekly comes from the Internet Archive.

The illustration of John Brown’s execution comes from The National Park Service’s John Brown’s Raid at Project Gutenberg.

I’m not getting any faster. The Tremont Temple commemoration was only a day after the anniversary of the hanging. It’s twenty days since the 160th anniversary of the Tremont fracas. I lost some of the dramatic effect of southern states pondering secession as December began. South Carolina promulgated an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860 … but at least other states in Dixie still had to decide! … at least from the perspective of 160 years ago

- [1]McFeely, William S. Frederick Douglass. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991. Print. page 208-211.↩