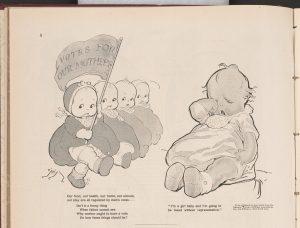

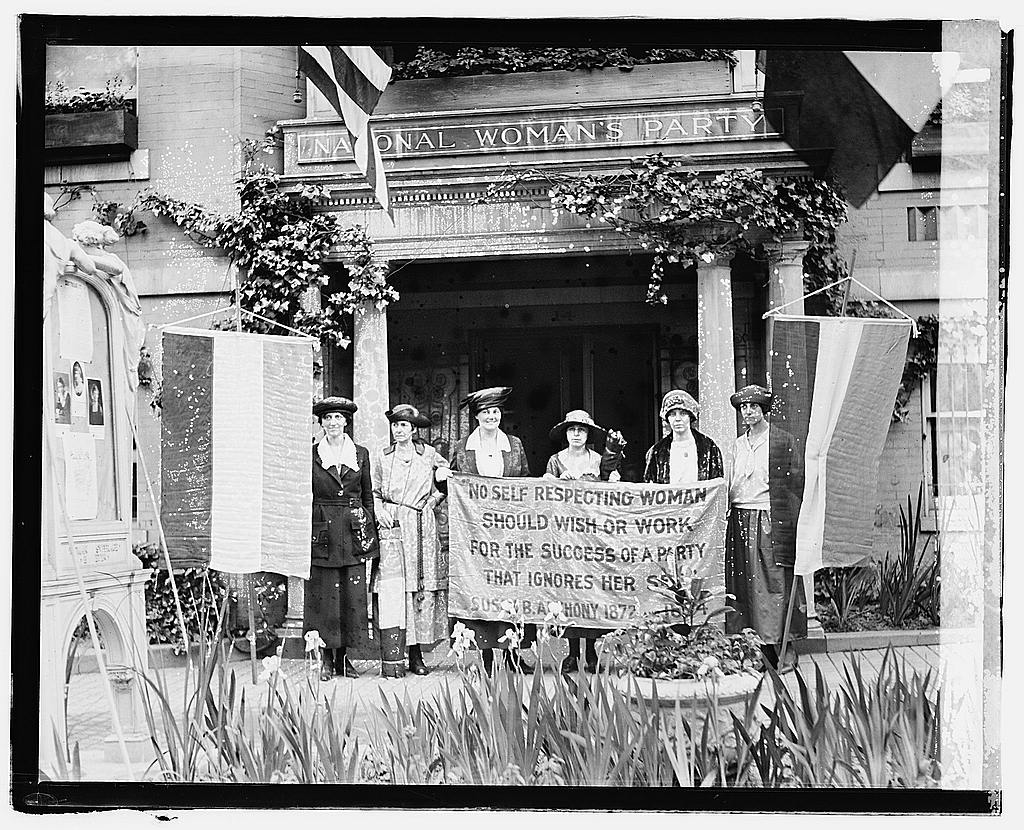

The magic number was .75, or at least that was the magic constant and had been since the U.S. federal constitution was promulgated in 1788. According to Article 5 of the Constitution, a proposed amendment that has been approved by two-thirds in the U.S. Senate and in the House will become law after three-fourths of the state legislatures approve it. The proposed Nineteenth Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote in the United States passed Congress in June 1919. Over the next year 35 states approved the amendment, but the magic number was 36 out of the 48 ststes. On August 18, 1920 Tennessee ratified the amendment; on August 26th the U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the results – the 19th amendment was law.

The front page of The New York Times on August 19, 1920 stated that both major political parties began targeting the new women voters immediately after the Tennessee vote and both major party presidential candidates said they were happy with the result. The paper got a couple sound bites. Democrat James M. Cox, the governor of Ohio, equated the passage of the amendment with the end of war: “The civilization of the world is saved. The mothers of America will stay the hand of war and repudiate those who traffic with a great principle. …” The presidential race was an all-Buckeye contest. U.S. Senator Warren G. Harding: “All along I have wished for the completion of ratification, and have said so, and I am glad to have all the citizenship of the United States take part in the Presidential elections. …”

_______________________________

Women had the right to vote in some states prior to the Nineteenth Amendment. The territory of Wyoming even passed woman’s suffrage way back in 1869; later Wyoming refused to accept statehood unless women could retain the right to vote; the U.S. Congress grudgingly agreed, so in 1890 Wyoming became the first state to allow women the vote. Between then and 1920 fourteen other states granted women full suffrage.

_______________________

New York State granted women the right to vote in 1917, but some New York women didn’t wait that long. On November 5, 1872 Susan B. Anthony and fourteen other women voted in Rochester, New York. These women and the three election officials who allowed them to vote were eventually arrested. According to the November 30, 1872 issue of The New-York Times, a federal official in Rochester examined the women on the 29th. The women admitted that they voted but claimed they were entitled to do so by the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. …

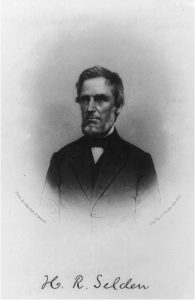

Susan B. Anthony was tried and convicted for illegal voting during June 1873 in federal court in Canandaigua New York. After she was convicted the three election inspectors who voted 2-1 to allow her to vote were also tried and convicted. You can read an account of the proceedings at Project Gutenberg. Here are a few parts of the presentation and argument by Henry R. Selden, Ms. Anthony’s attorney:

… Before the registration, and before this election, Miss Anthony called upon me for advice upon the question whether, under the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, she had a right to vote. I had not examined the question. I told her I would examine it and give her my opinion upon the question of her legal right. She went away and came again after I had made the examination. I advised her that she was as lawful a voter as I am, or as any other man is, and advised her to go and offer her vote. I may have been mistaken in that, and if I was mistaken, I believe she acted in good faith. I believe she acted according to her right as the law and Constitution gave it to her. But whether she did or not, she acted in the most perfect good faith, and if she made a mistake, or if I made one, that is not a reason for committing her to a felon’s cell. …

Women have the same interest that men have in the establishment and maintenance of good government; they are to the same extent as men bound to obey the laws; they suffer to the same extent by bad laws, and profit to the same extent by good laws; and upon principles of equal justice, as it would seem, should be allowed equally with men, to express their preference in the choice of law-makers and rulers. But however that may be, no greater absurdity, to use no harsher term, could be presented, than that of rewarding men and punishing women, for the same act, without giving to women any voice in the question which should be rewarded, and which punished. …

Miss Anthony, and those united with her in demanding the right of suffrage, claim, and with a strong appearance of justice, that upon the principles upon which our government is founded, and which lie at the basis of all just government, every citizen has a right to take part, upon equal terms with every other citizen, in the formation and administration of government. This claim on the part of the female sex presents a question the magnitude of which is not well appreciated by the writers and speakers who treat it with ridicule. Those engaged in the movement are able, sincere and earnest women, and they will not be silenced by such ridicule, nor even by the villainous caricatures of Nast. On the contrary, they justly place all those things to the account of the wrongs which they think their sex has suffered. They believe, with an intensity of feeling which men who have not associated with them have not yet learned, that their sex has not had, and has not now, its just and true position in the organization of government and society. They may be wrong in their position, but they will not be content until their arguments are fairly, truthfully and candidly answered.

In the most celebrated document which has been put forth on this side of the Atlantic, our ancestors declared that “governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.” …

By reference to the provisions of the original Constitution, here recited, it appears that prior to the thirteenth, if not until the fourteenth, amendment, the whole power over the elective franchise, even in the choice of Federal officers, rested with the States. The Constitution contains no definition of the term “citizen,” either of the United States, or of the several States, but contents itself with the provision that “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens of the several States.” The States were thus left free to place such restrictions and limitations upon the “privileges and immunities” of citizens as they saw fit, so far as is consistent with a republican form of government, subject only to the condition that no State could place restrictions upon the “privileges or immunities” of the citizens of any other State, which would not be applicable to its own citizens under like circumstances.

It will be seen, therefore, that the whole subject, as to what should constitute the “privileges and immunities” of the citizen being left to the States, no question, such as we now present, could have arisen under the original constitution of the United States.

But now, by the fourteenth amendment, the United States have not only declared what constitutes citizenship, both in the United States and in the several States, securing the rights of citizens to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States;” but have absolutely prohibited the States from making or enforcing “any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.“

By virtue of this provision, I insist that the act of Miss Anthony in voting was lawful.

It has never, since the adoption of the fourteenth amendment, been questioned, and cannot be questioned, that women as well as men are included in the terms of its first section, nor that the same “privileges and immunities of citizens” are equally secured to both. …

If we go to the lexicographers and to the writers upon law, to learn what are the privileges and immunities of the “citizen” in a republican government, we shall find that the leading feature of citizenship is the enjoyment of the right of suffrage.

The definition of the term “citizen” by Bouvier is: “One who under the constitution and laws of the United States, has a right to vote for Representatives in Congress, and other public officers, and who is qualified to fill offices in the gift of the people.”

By Worcester—”An inhabitant of a republic who enjoys the rights of a freeman, and has a right to vote for public officers.”

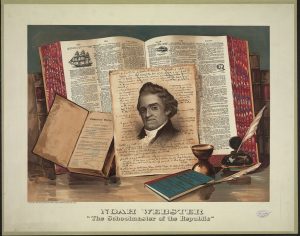

By Webster—”In the United States, a person, native or naturalized, who has the privilege of exercising the elective franchise, or the qualifications which enable him to vote for rulers, and to purchase and hold real estate.”

The meaning of the word “citizen” is directly and plainly recognized by the latest amendment of the constitution (the fifteenth.)

“The right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any State, on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This clause assumes that the right of citizens, as such, to vote, is an existing right.

Mr. Richard Grant White, in his late work on Words and their Uses, says of the word citizen: “A citizen is a person who has certain political rights, and the word is properly used only to imply or suggest the possession of these rights.”

Mr. Justice Washington, in the case of Corfield vs. Coryell (4 Wash, C.C. Rep. 380), speaking of the “privileges and immunities” of the citizen, as mentioned in Sec. 2, Art. 4, of the constitution, after enumerating the personal rights mentioned above, and some others, as embraced by those terms, says, “to which may be added the elective franchise, as regulated and established by the laws or constitution of the State in which it is to be exercised.” At that time the States had entire control of the subject, and could abridge this privilege of the citizen at its pleasure; but the judge recognizes the “elective franchise” as among the “privileges and immunities” secured, to a qualified extent, to the citizens of every State by the provisions of the constitution last referred to. When, therefore, the States were, by the fourteenth amendment, absolutely prohibited from abridging the privileges of the citizen, either by enforcing existing laws, or by the making of new laws, the right of every “citizen” to the full exercise of this privilege, as against State action, was absolutely secured.

Chancellor Kent and Judge Story both refer to the opinion of Mr. Justice Washington, above quoted, with approbation.

The Supreme Court of Kentucky, in the case of Amy, a woman of color, vs. Smith (1 Littell’s Rep. 326), discussed with great ability the questions as to what constituted citizenship, and what were the “privileges and immunities of citizens” which were secured by Sec. 2, Art. 4, of the constitution, and they showed, by an unanswerable argument, that the term “citizens,” as there used, was confined to those who were entitled to the enjoyment of the elective franchise, and that that was among the highest of the “privileges and immunities” secured to the citizen by that section. The court say that, “to be a citizen it is necessary that he should be entitled to the enjoyment of these privileges and immunities, upon the same terms upon which they are conferred upon other citizens; and unless he is so entitled, he cannot, in the proper sense of the term, be a citizen.”

In the case of Scott vs. Sanford (19 How. 404), Chief Justice Taney says: “The words ‘people of the United States,’ and ‘citizens,’ are synonymous terms, and mean the same thing; they describe the political body, who, according to our republican institutions, form the sovereignty and hold the power, and conduct the government through their representatives. They are what we familiarly call the sovereign people, and every citizen is one of this people, and a constituent member of this sovereignty.”

As the judge was about to pronounce Ms. Anthony’s sentence the following exchange reportedly took place:

Judge Hunt—(Ordering the defendant to stand up), “Has the prisoner anything to say why sentence shall not be pronounced?”

Miss Anthony—Yes, your honor, I have many things to say; for in your ordered verdict of guilty, you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored. Robbed of the fundamental privilege of citizenship, I am degraded from the status of a citizen to that of a subject; and not only myself individually, but all of my sex, are, by your honor’s verdict, doomed to political subjection under this, so-called, form of government.

Judge Hunt—The Court cannot listen to a rehearsal of arguments the prisoner’s counsel has already consumed three hours in presenting.

Miss Anthony—May it please your honor, I am not arguing the question, but simply stating the reasons why sentence cannot, in justice, be pronounced against me. Your denial of my citizen’s right to vote, is the denial of my right of consent as one of the governed, the denial of my right of representation as one of the taxed, the denial of my right to a trial by a jury of my peers, as an offender against law, therefore, the denial of my sacred rights to life, liberty, property and—

Judge Hunt—The Court cannot allow the prisoner to go on.

Miss Anthony—But your honor will not deny me this one and only poor privilege of protest against this high-handed outrage upon my citizen’s rights. May it please the Court to remember that since the day of my arrest last November, this is the first time that either myself or any person of my disfranchised class has been allowed a word of defense before judge or jury—

Judge Hunt—The prisoner must sit down—the Court cannot allow it.

Miss Anthony—All of my prosecutors, from the 8th ward corner grocery politician, who entered the complaint, to the United States Marshal, Commissioner, District Attorney, District Judge, your honor on the bench, not one is my peer, but each and all are my political sovereigns; and had your honor submitted my case to the jury, as was clearly your duty, even then I should have had just cause of protest, for not one of those men was my peer; but, native or foreign born, white or black, rich or poor, educated or ignorant, awake or asleep, sober or drunk, each and every man of them was my political superior; hence, in no sense, my peer. Even, under such circumstances, a commoner of England, tried before a jury of Lords, would have far less cause to complain than should I, a woman, tried before a jury of men. Even my counsel, the Hon. Henry R. Selden, who has argued my cause so ably, so earnestly, so unanswerably before your honor, is my political sovereign. Precisely as no disfranchised person is entitled to sit upon a jury, and no woman is entitled to the franchise, so, none but a regularly admitted lawyer is allowed to practice in the courts, and no woman can gain admission to the bar—hence, jury, judge, counsel, must all be of the superior class.

Judge Hunt—The Court must insist—the prisoner has been tried according to the established forms of law.

Miss Anthony—Yes, your honor, but by forms of law all made by men, interpreted by men, administered by men, in favor of men, and against women; and hence, your honor’s ordered verdict of guilty, against a United States citizen for the exercise of “that citizen’s right to vote,” simply because that citizen was a woman and not a man. But, yesterday, the same man made forms of law, declared it a crime punishable with $1,000 fine and six months’ imprisonment, for you, or me, or any of us, to give a cup of cold water, a crust of bread, or a night’s shelter to a panting fugitive as he was tracking his way to Canada. And every man or woman in whose veins coursed a drop of human sympathy violated that wicked law, reckless of consequences, and was justified in so doing. As then, the slaves who got their freedom must take it over, or under, or through the unjust forms of law, precisely so, now, must women, to get their right to a voice in this government, take it; and I have taken mine, and mean to take it at every possible opportunity.

Judge Hunt—The Court orders the prisoner to sit down. It will not allow another word.

Miss Anthony—When I was brought before your honor for trial, I hoped for a broad and liberal interpretation of the Constitution and its recent amendments, that should declare all United States citizens under its protecting ægis—that should declare equality of rights the national guarantee to all persons born or naturalized in the United States. But failing to get this justice—failing, even, to get a trial by a jury not of my peers—I ask not leniency at your hands—but rather the full rigors of the law.

Judge Hunt—The Court must insist—

(Here the prisoner sat down.)

Judge Hunt—The prisoner will stand up.

(Here Miss Anthony arose again.)

The sentence of the Court is that you pay a fine of one hundred dollars and the costs of the prosecution.

Miss Anthony—May it please your honor, I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty. All the stock in trade I possess is a $10,000 debt, incurred by publishing my paper—The Revolution—four years ago, the sole object of which was to educate all women to do precisely as I have done, rebel against your man-made, unjust, unconstitutional forms of law, that tax, fine, imprison and hang women, while they deny them the right of representation in the government; and I shall work on with might and main to pay every dollar of that honest debt, but not a penny shall go to this unjust claim. And I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, that “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

Judge Hunt—Madam, the Court will not order you committed until the fine is paid.