On July 2, 1776 the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia voted for independence from Great Britain. On July 4th the Congress agreed to the words in the written Declaration. July 8th was a “great day of celebration” in Philadelphia as the Declaration was read aloud to crowd in the State House Yard; bells rang, bonfires burned, candles illuminated windows and the King’s Arms was removed from a room at the State House and thrown on a huge fire. [1]. 244 years ago today the Declaration of Independence was read to the American army in New York City. From the July 9, 1870 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

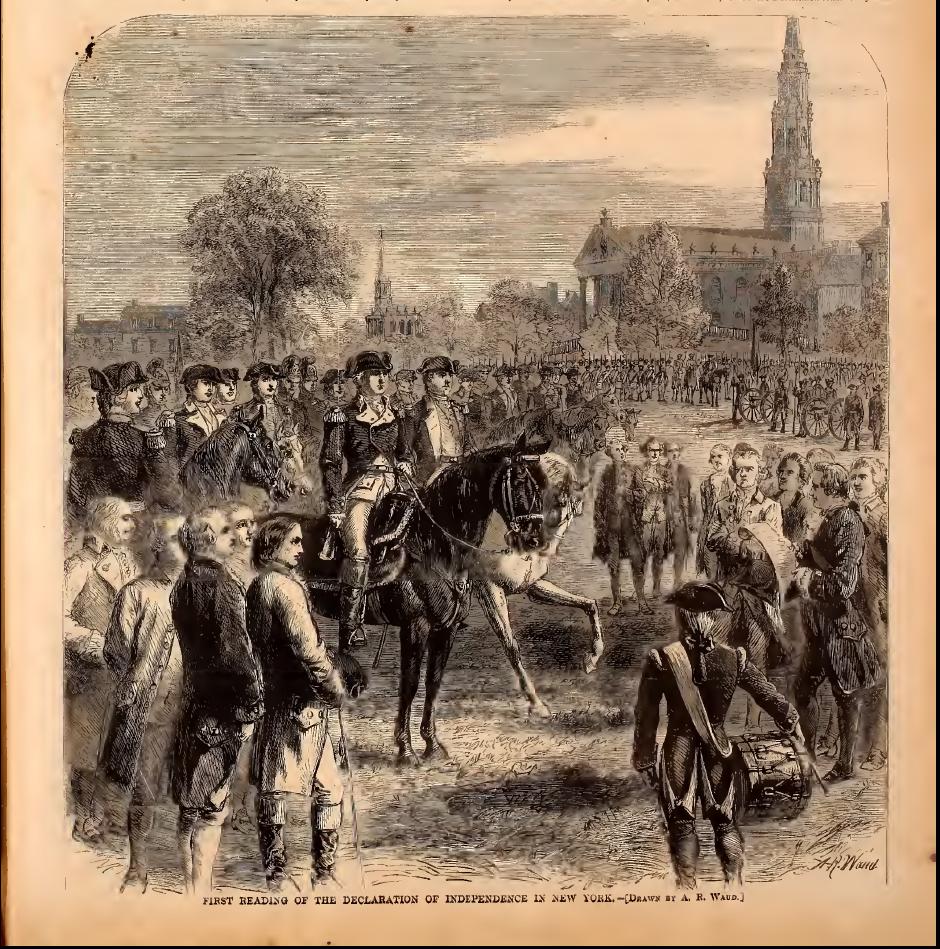

THE illustration underneath commemorates one of the most interesting events in the history of New York – the first reading of the Declaration of Independence to the American army, by order of General WASHINGTON – of which we find the following account in LOSSING’S “Field-Book of the Revolution:” “WASHINGTON received the Declaration on the 9th of July, 1776, with instructions to have it read to the army. He immediately issued an order for the several brigades, then in and near the city, to be drawn up at six o’clock that evening, to hear it read by their several commanders or their aids. The brigades were formed in hollow squares on their respective parades. The venerable ZACHARIAH GREENE (commonly known as ‘Parson Greene,’ the father-in-law of Mr. THOMPSON, historian of Long Island, yet (1855) living at Hempstead, at the age of ninety-six years, informed me that he belonged to the brigade then encamped on the ‘Common,’ where the City Hall now stands. The hollow square was formed at about the spot where the Park fountain now is. He says WASHINGTON was within the square, on horseback, and that the Declaration was read in a clear voice by one of his aids. When it was concluded three hearty cheers were given. HOLT’S Journal for July 11, 1776, says: ‘In pursuance of the Declaration of Independence, a general jail delivery took place with respect to debtors.’ Ten days afterward, the people assembled at the City Hall, at the head of Broad Street, to hear the Declaration read. They then took the British arms from over the seat of justice in the court-room, also the arms wrought in stone in front of the building, and the picture of the king in the council chamber, and destroyed them, by fire, in the street. They also ordered the British arms in all the churches in the city to be destroyed. This order seems not to have been obeyed. Those in Trinity Church were taken down and carried to New Brunswick by the Rev. CHARLES INGLIS, at the close of the war, and now hang upon the walls of a Protestant Episcopal church in St. John.”

According to Scientific American, during the evening of July 9, 1776 a crowd pulled down a statue of King George III in Bowling Green on Manhattan. The article agrees with Harper’s that patriots also practiced “defacing and destroying examples of the royal arms where they were found.”

On July 3, 1776 John Adams wrote two letters to his wife Abigail. He thought the day before, when the Continental Congress voted for independence from Great Britain, would be the big day Americans celebrated in the future, fireworks on the Second. From Familiar Letters of John Adams and His Wife

Abigail Adams During the Revolution:

114. John Adams.

3 July, 1776.

… Yesterday, the greatest question was decided which ever was debated in America, and a greater, perhaps, never was nor will be decided among men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony “that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, and as such they have, and of right ought to have, full power to make war, conclude peace, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which other States may rightfully do.” You will see, in a few days, a Declaration setting forth the causes which have impelled us to this mighty revolution, and the reasons which will justify it in the sight of God and man. A plan of confederation will be taken up in a few days.

When I look back to the year 1761, and recollect the argument concerning writs of assistance in the superior court, which I have hitherto considered as the commencement of this controversy between Great Britain and America, and run through the whole period from that time to this, and recollect the series of political events, the chain of causes and effects, I am surprised at the suddenness as well as greatness of this revolution. Britain has been filled with folly, and America with wisdom; at least, this is my judgment. Time must determine. It is the will of Heaven that the two countries should be sundered forever. It may be the will of Heaven that America shall suffer calamities still more wasting, and distresses yet more dreadful. If this is to be the case, it will have this good effect at least. It will inspire us with many virtues which we have not, and correct many errors, follies, and vices which threaten to disturb, dishonor, and destroy us. The furnace of affliction produces refinement in states as well as individuals. And the new Governments we are assuming in every part will require a purification from our vices, and an augmentation of our virtues, or they will be no[192] blessings. The people will have unbounded power, and the people are extremely addicted to corruption and venality, as well as the great. But I must submit all my hopes and fears to an overruling Providence, in which, unfashionable as the faith may be, I firmly believe.

115. John Adams.

Philadelphia, 3 July, 1776.

Had a Declaration of Independency been made seven months ago, it would have been attended with many great and glorious effects. We might, before this hour, have formed alliances with foreign states. We should have mastered Quebec, and been in possession of Canada. You will perhaps wonder how such a declaration would have influenced our affairs in Canada, but if I could write with freedom, I could easily convince you that it would, and explain to you the manner how. Many gentlemen in high stations, and of great influence, have been duped by the ministerial bubble of Commissioners to treat. And in real, sincere expectation of this event, which they so fondly wished, they have been slow and languid in promoting measures for the reduction of that province. Others there are in the Colonies who really wished that our enterprise in Canada would be defeated, that the Colonies might be brought into danger and distress between two fires, and be thus induced to submit. Others really wished to defeat the expedition to Canada, lest the conquest of it should elevate the minds of the people too much to hearken to those terms of reconciliation which, they believed, would be offered us. These jarring views, wishes, and designs occasioned an opposition to many salutary measures which were proposed for the support of that expedition, and caused obstructions, embarrassments, and studied delays, which have finally lost us the province.

All these causes, however, in conjunction would not have disappointed us, if it had not been for a misfortune which could not be foreseen, and perhaps could not have been prevented; I mean the prevalence of the small-pox among our troops. This fatal pestilence completed our destruction. It is a frown of Providence upon us, which we ought to lay to heart.

But, on the other hand, the delay of this Declaration to this time has many great advantages attending it. The hopes of reconciliation which were fondly entertained by multitudes of honest and well-meaning, though weak and mistaken people, have been gradually, and at last totally extinguished. Time has been given for the whole people maturely to consider the great question of independence, and to ripen their judgment, dissipate their fears, and allure their hopes, by discussing it in newspapers and pamphlets, by debating it in assemblies, conventions, committees of safety and inspection, in town and county meetings, as well as in private conversations, so that the whole people, in every colony of the thirteen, have now adopted it as their own act. This will cement the union, and avoid those heats, and perhaps convulsions, which might have been occasioned by such a Declaration six months ago.

But the day is past. The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.

You will think me transported with enthusiasm, but I am not. I am well aware of the toil and blood and treasure that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration and support and defend these States. Yet, through all the gloom, I can see the rays of ravishing light and glory. I can see that the end is more than worth all the means. And that posterity will triumph in that day’s transaction, even although we should rue it, which I trust in God we shall not.

The book of letters was edited by John and Abigail’s grandson, Charles Francis Adams, who, in a footnote, said he checked the facts and corrected a previous “slight alteration” by relative.

FOOTNOTES:

[146] The practice has been to celebrate the 4th of July, the day upon which the form of the Declaration of Independence was agreed to, rather than the 2d, the day upon which the resolution making that declaration was determined upon by the Congress. A friend of Mr. Adams, who had during his lifetime an opportunity to read the two letters dated on the 3d, was so much struck with them, that he procured the liberty to publish them. But thinking, probably, that a slight alteration would better fit them for the taste of the day, and gain for them a higher character for prophecy, than if printed as they were, he obtained leave to put together only the most remarkable paragraphs, and make one letter out of the two. He then changed the date from the 3d to the 5th, and the word second to fourth, and published it, the public being made aware of these alterations. In this form, and as connected with the anniversary of our National Independence, these letters have ever since enjoyed great popularity. The editor at first entertained some doubt of the expediency of making a variation by printing them in their original shape. But upon considering the matter maturely, his determination to adhere, in all cases, to the text prevailed. If any injury to the reputation of Mr. Adams for prophecy should ensue, it will be more in form than in substance, and will not be, perhaps, without compensation in the restoration of the unpublished portion. This friend was a nephew, William S. Shaw. But the letters had been correctly and fully printed before. See Niles’s Principles and Acts of the Revolution, p. 330.

According to Wikipedia:

“Following the British occupation of New York in 1777, [Charles] Inglis was promoted from curate to rector of Trinity Church. As a Loyalist, it is recorded that Inglis prayed aloud for King George III while George Washington was in the congregation. The church was quickly surrounded by militia. Inglis’ home was plundered. In November 1783, upon the evacuation of Loyalists from New York, Inglis returned to England. However, his whole congregation of Trinity Church went to Nova Scotia.” [George Washington might have been in the congregation in 1776]

According to Find a Grave, Reverend Zachariah Greene “Served three years in the Revolutionary War (from Jan 1776 to Jan 1779); during which time he was engaged in three severe battles: Throgg’s Point, White Plains, and White Marsh (northwest of Philadelphia). He was wounded at the Battle of White Marsh on Dec 7, 1777, a musket ball entering his left shoulder fracturing the scapula and clavicle.” He later became a preacher and served as pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Brookhaven (Setauket) on Long Island from 1797 until his death in 1858.

Harper’s Weekly for 1870 is at the Internet Archive

You can find the Adams book of correspondence at Project Gutenberg. The two letters here are on pages 190-194.

From the Library of Congress: the print said to be from 1851; statue pulled down by slaves (there might have been slaves in the crowd, but they wouldn’t have done all the tearing down; apparently King George was dressed as an ancient Roman, Marcus Aurelius); Johannes A. Oertel’s romanticized picture; His most gracious majesty King George the Third

[July 10, 2020]I added the fake history tag. *** A little embarrassing, maybe I’ve been watching too many movies; there’s evidence that no slaves, Hebrew or otherwise, helped build the pyramids. I apologize.

- [1]McCullough, David. John Adams. New York: Simon & Schuster paperbacks, 2004. Print. pages 136-137.↩