The Fourth of July 1863 was a glad day for the Union during the American Civil War. Rebels surrendered Vicksburg, Mississippi to Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant, and that evening the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began to head back South after three bloody days at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. A few days later President Abraham Lincoln focused on Independence Day in some off the cuff remarks to a group of serenaders. From The Papers And Writings Of Abraham Lincoln, Volume Six at Project Gutenberg:

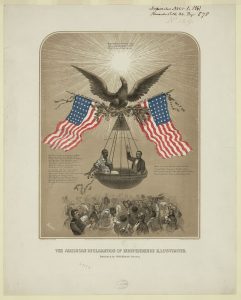

“All Men Are Created Equal” and “Stand by the Declaration.”

RESPONSE TO A SERENADE,

JULY 7, 1863.

FELLOW-CITIZENS:—I am very glad indeed to see you to-night, and yet I will not say I thank you for this call; but I do most sincerely thank Almighty God for the occasion on which you have called. How long ago is it Eighty-odd years since, on the Fourth of July, for the first time in the history of the world, a nation, by its representatives, assembled and declared as a self-evident truth “that all men are created equal.” That was the birthday of the United States of America. Since then the Fourth of July has had several very peculiar recognitions. The two men most distinguished in the framing and support of the Declaration were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the one having penned it, and the other sustained it the most forcibly in debate—the only two of the fifty-five who signed it and were elected Presidents of the United States. Precisely fifty years after they put their hands to the paper, it pleased Almighty God to take both from this stage of action. This was indeed an extraordinary and remarkable event in our history. Another President, five years after, was called from this stage of existence on the same day and month of the year; and now on this last Fourth of July just passed, when we have a gigantic rebellion, at the bottom of which is an effort to overthrow the principle that all men were created equal, we have the surrender of a most powerful position and army on that very day. And not only so, but in the succession of battles in Pennsylvania, near to us, through three days, so rapidly fought that they might be called one great battle, on the first, second, and third of the month of July; and on the fourth the cohorts of those who opposed the Declaration that all men are created equal, “turned tail” and run.

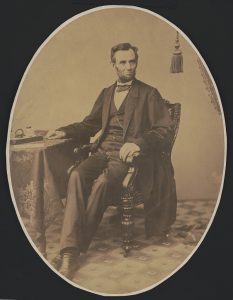

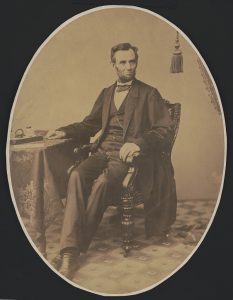

President Lincoln November 8, 1863

Gentlemen, this is a glorious theme, and the occasion for a speech, but I am not prepared to make one worthy of the occasion. I would like to speak in terms of praise due to the many brave officers and soldiers who have fought in the cause of the Union and liberties of their country from the beginning of the war. These are trying occasions, not only in success, but for the want of success. I dislike to mention the name of one single officer, lest I might do wrong to those I might forget. Recent events bring up glorious names, and particularly prominent ones; but these I will not mention. Having said this much, I will now take the music.

The president did prepare a speech with a couple of these ideas for his visit to Gettysburg about four months later. Many people think his words there for the dedication of the soldiers’ national cemetery were “worthy of the occasion.”

Based on correspondence all around July 7th, it seems that President Lincoln wanted a little more success from General Meade and his Army of the Potomac as the rebels retreated from Gettysburg:

“turned tail” and run?

ANNOUNCEMENT OF NEWS FROM GETTYSBURG.

WASHINGTON,

July 4, 10.30 A.M.

The President announces to the country that news from the Army of the Potomac, up to 10 P.M. of the 3d, is such as to cover that army with the highest honor, to promise a great success to the cause of the Union, and to claim the condolence of all for the many gallant fallen; and that for this he especially desires that on this day He whose will, not ours, should ever be done be everywhere remembered and reverenced with profoundest gratitude.

A. LINCOLN.

TELEGRAM TO GENERAL FRENCH. [Cipher] WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, D. C.,

July 5, 1863.

MAJOR-GENERAL FRENCH, Fredericktown, Md.:

I see your despatch about destruction of pontoons. Cannot the enemy ford the river?

A. LINCOLN.

CONTINUED FAILURE TO PURSUE ENEMY

TELEGRAM TO GENERAL H. W. HALLECK.

SOLDIERS’ HOME, WASHINGTON, JULY 6 1863.7 P.M., MAJOR-GENERAL HALLECK:

I left the telegraph office a good deal dissatisfied. You know I did not like the phrase—in Orders, No. 68, I believe—”Drive the invaders from our soil.” Since that, I see a despatch from General French, saying the enemy is crossing his wounded over the river in flats, without saying why he does not stop it, or even intimating a thought that it ought to be stopped. Still later, another despatch from General Pleasonton, by direction of General Meade, to General French, stating that the main army is halted because it is believed the rebels are concentrating “on the road towards Hagerstown, beyond Fairfield,” and is not to move until it is ascertained that the rebels intend to evacuate Cumberland Valley.

These things appear to me to be connected with a purpose to cover Baltimore and Washington and to get the enemy across the river again without a further collision, and they do not appear connected with a purpose to prevent his crossing and to destroy him. I do fear the former purpose is acted upon and the latter rejected.

If you are satisfied the latter purpose is entertained, and is judiciously pursued, I am content. If you are not so satisfied, please look to it.

Yours truly,

A. LINCOLN.

…

SURRENDER OF VICKSBURG TO GENERAL GRANT

TELEGRAM FROM GENERAL HALLECK TO GENERAL G. C. MEADE.

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 7, 1863.

MAJOR-GENERAL MEADE, Army of the Potomac:

I have received from the President the following note, which I respectfully communicate:

“We have certain information that Vicksburg surrendered to General Grant on the Fourth of July. Now if General Meade can complete his work, so gloriously prosecuted this far, by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee’s army, the rebellion will be over.

“Yours truly,

“A. LINCOLN.”

H. W. HALLECK. General-in-Chief.

TELEGRAM FROM GENERAL HALLECK TO GENERAL G. C. MEADE.

WASHINGTON, D. C., July 8, 1863.

MAJOR-GENERAL MEADE, Frederick, Md.:

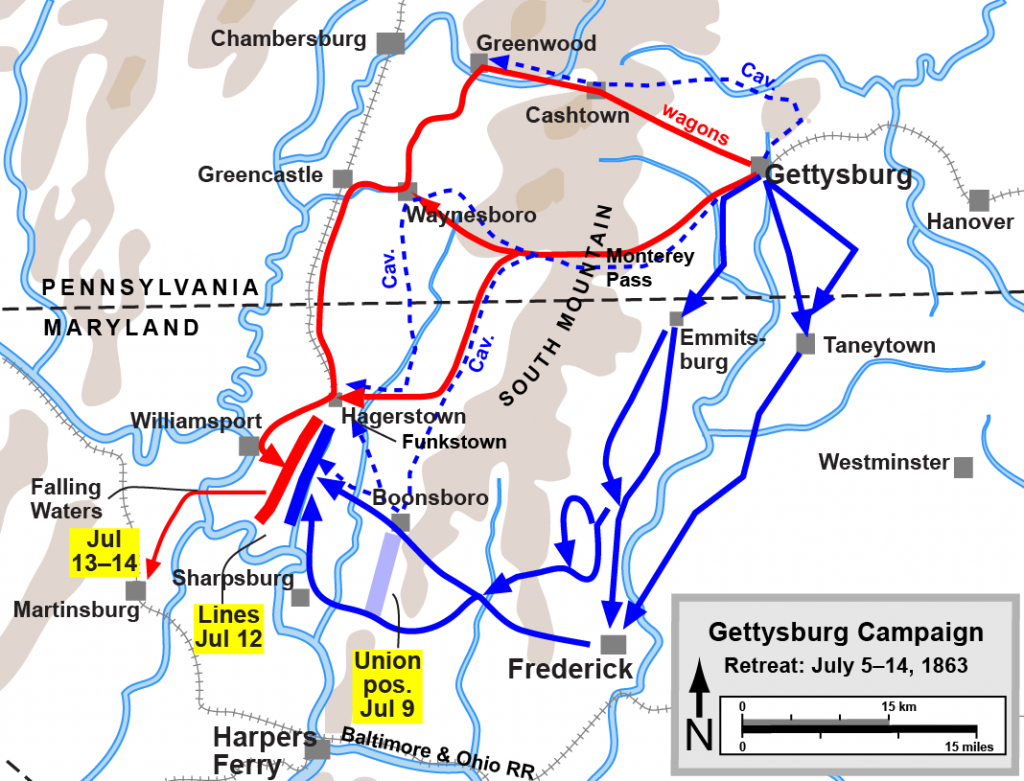

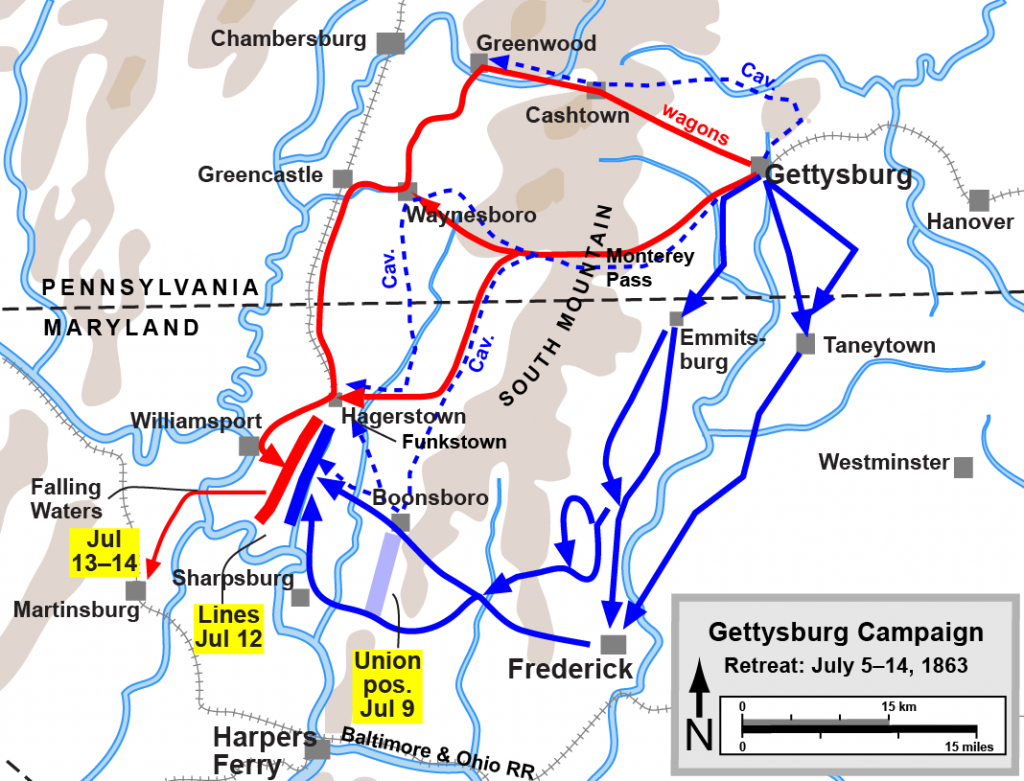

There is reliable information that the enemy is crossing at Williamsport. The opportunity to attack his divided forces should not be lost. The President is urgent and anxious that your army should move against him by forced marches.

H. W. HALLECK, General-in-Chief

TELEGRAM TO GENERAL THOMAS.

WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, July 8, 1863.12.30 P.M.

GENERAL LORENZO THOMAS, Harrisburg, Pa.:

Your despatch of this morning to the Secretary of War is before me. The forces you speak of will be of no imaginable service if they cannot go forward with a little more expedition. Lee is now passing the Potomac faster than the forces you mention are passing Carlisle. Forces now beyond Carlisle to be joined by regiments still at Harrisburg, and the united force again to join Pierce somewhere, and the whole to move down the Cumberland Valley, will in my unprofessional opinion be quite as likely to capture the “man in the moon” as any part of Lee’s army.

A. LINCOLN.

the getaway

The third U.S. president alluded to by Mr. Lincoln was James Monroe, who died on July 4, 1831.

[07/04/2020 PM] Of course, It would take many years for “all men” to include all women.

Hal Jespersen’s map of the retreat from Gettysburg (Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW) is licensed under Creative Commons

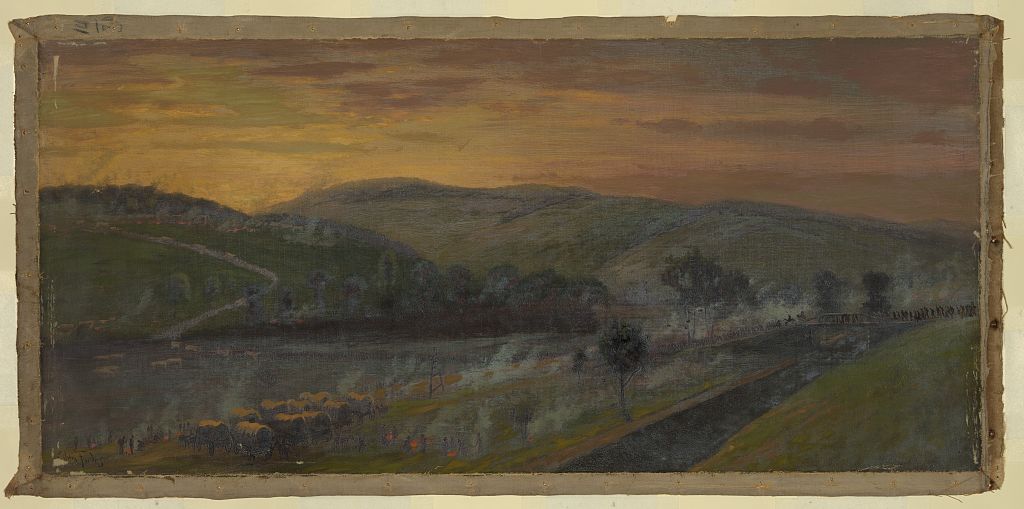

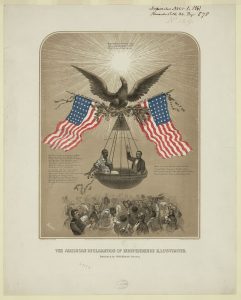

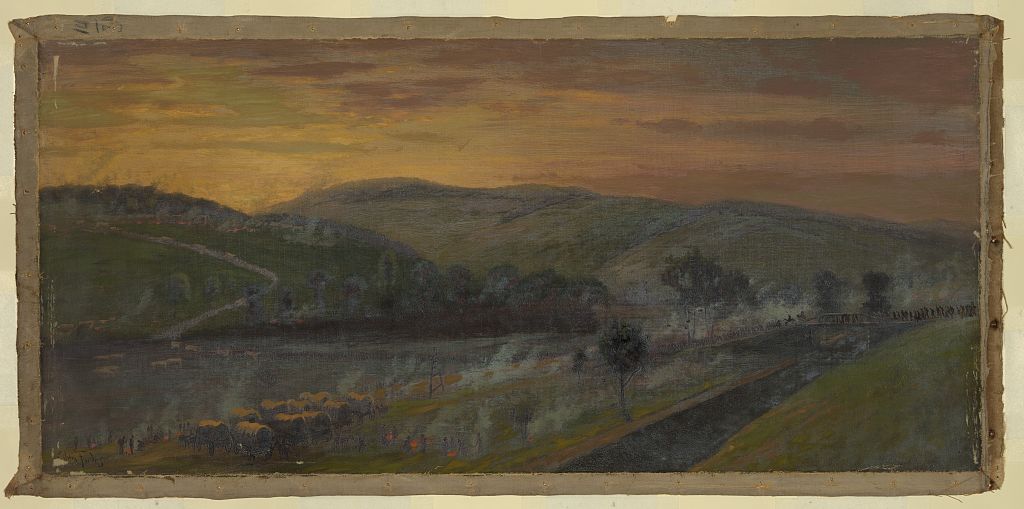

From the Library of Congress: the illustrated Declaration circa 1861, when emancipation was still in the future; Alexander Gardner’s portrait; Edwin Forbes’ Escape over the Potomac near Williamsport;