a scholar and a poet

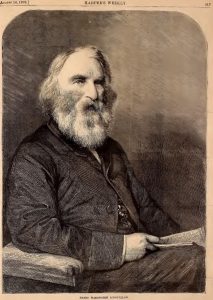

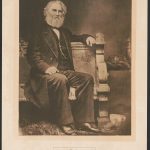

Way back in its August 14, 1869 issue, Harper’s Weekly profiled a famous American man of letters:

HENRY W. LONGFELLOW.

Now that LONGFELLOW — the most popular of American poets — is in England, the question is naturally asked, What do Englishmen

think of him? In reply it may he said that Longfellow is, in England, more popular than TENNYSON. It is also true that Tennyson is more popular in this country than Longfellow. This seems strange at the first glance; but the reason is obvious. Longfellow’s poems are cheaper in England than here; and Tennyson’s may be bought here at a nominal price as compared with their cost to an English reader. Is there not here a strong argument against an international copyright, which would exclude both TENNYSON and” LONGFELLOW from the poorest classes?

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW was born at Portland, Maine, February 27, 1807. He is now, therefore, nearly sixty-three years old. His father, the Hon. STEPHEN LONGFELLOW, was an eminent lawyer. He entered Bowdoin College at the early age of fourteen, and during his course he gave evidence of those abilities which have given him such high distinction both as a scholar and a poet. Among his productions at this period may be mentioned his “Hymn of the Moravian Nuns,” “The Spirit of Poetry,” “The Woods in Winter,” and “Sunrise on the Hills.” After his graduation he seems to have some vague idea of adopting the legal profession. But a more congenial occupation offered. He was appointed Professor of Modern Languages and Literature at Bowdoin College, with the privilege of residing some years abroad. In 1826 he sailed for Europe, and during that and the two following years he made a tour of France, Spain, Italy, and Germany. He returned home in 1830, and entered upon the duties of his professorship, which he held for five years, when he accepted a similar position in Harvard College, succeeding Mr. GEORGE TICKNOR. He, in 1835 and 1836, made another European tour through Denmark, Sweden, Holland, Germany, and Switzerland. In 1854 he resigned his position, and has since resided at Cambridge. …

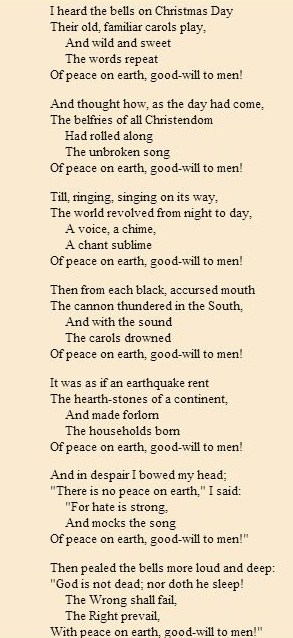

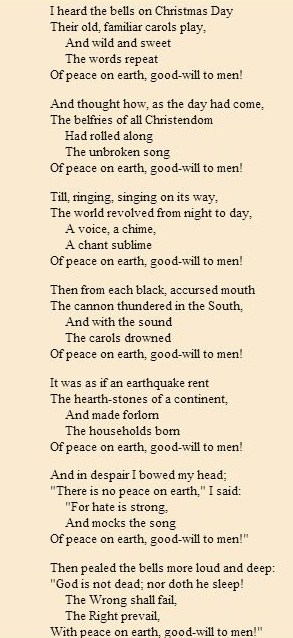

The article went on to analyze several of Mr. Longfellow’s works and concluded that “His countrymen may well be proud of him.” I don’t specifically remember reading any of the works mentioned but have certainly heard of many of them, for example, “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” I might have read that) But my question is, “What about the big one?” – What about “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day”? Just as I enjoy reading and rereading about the Civil War, I enjoy hearing the same old Christmas carols every year – like “I Heard the Bells,” which was influenced by the American Civil War. The Harper’s Weekly piece didn’t really go into Mr. Longfellow’s personal life, but, according to Wikipedia, his life experiences were crucial to the poem:

within bell range?

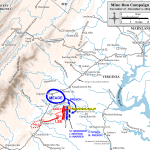

In 1861, two years before writing this poem, Longfellow’s personal peace was shaken when his second wife of 18 years, to whom he was very devoted, was fatally burned in an accidental fire. Then in 1863, during the American Civil War, Longfellow’s oldest son, Charles Appleton Longfellow, joined the Union Army without his father’s blessing. Longfellow was informed by a letter dated March 14, 1863, after Charles had left. “I have tried hard to resist the temptation of going without your leave but I cannot any longer”, he wrote. “I feel it to be my first duty to do what I can for my country and I would willingly lay down my life for it if it would be of any good.” Charles was soon appointed as a lieutenant but, in November, he was severely wounded in the Battle of New Hope Church, Virginia, during the Mine Run Campaign. Charles eventually recovered, but his time as a soldier was finished.

Longfellow wrote the poem on Christmas Day in 1863. “Christmas Bells” was first published in February 1865, in Our Young Folks, a juvenile magazine published by Ticknor and Fields.”

“Christmas Bells” From The Complete Poetical Works of Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow at Project Gutenberg

war song

Charles wounded on November 27th

drowning out the carols

lots to ponder

____________________________

I think about Mr. Longfellow’s poem just about every Christmas. This year I also thought about the ending of Amanda Foreman’s book about British-American relations during the Civil War ((just ahead of the Epilogue). British-born Doctor Elizabeth Blackwell trained Union nurses throughout the American Civil War. She wrote to a friend about the suffering the war caused and how President Lincoln empathized with all the pain:

You cannot hardly understand and I cannot explain how our private lives have all become interwoven with the life of the nation’s. No one who has not lived through it can understand the bond between those who have. … Neither is it possible without this intense and prolonged experience to estimate the keen personal suffering that has entered into every household and saddened every life. … The great secret of our dead leader’s popularity was the wonderful instinct with which he felt and acted … he did not lead, he expressed the American heartbreak … it has been to me a revelation to feel such influence and to see such leadership. I never was thoroughly republican before … but I am so, thoroughly, now.[]

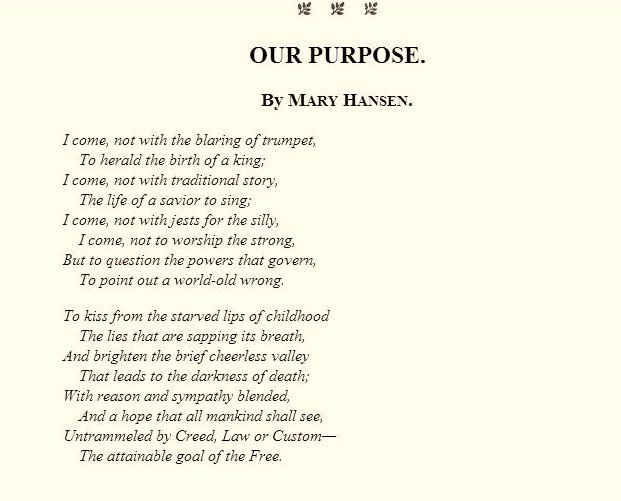

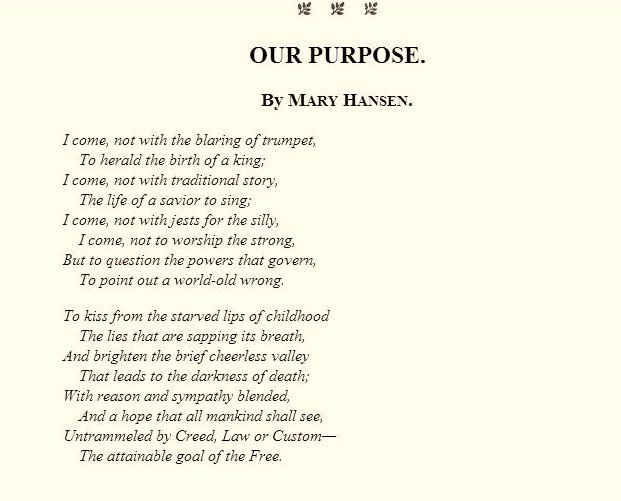

“Christmas Bells” asks a couple questions that humans have been asking for millennia: Does God exist? If God exists, then why does x [something horrible] occur? Recently I’ve read a couple items that seem to have different takes those issues. From the April 1906 issue of Mother Earth:

Christmas isn’t for children

About 74 years ago Daniel Russell quoted Charles A. Beard:

I am convinced that life is not a mere bog in which men and women tangle themselves in the mire and die. Something magnificent is taking place here … and the supreme challenge … is that of making the noblest and best in our curious heritage prevail.[]

_____________________________________________

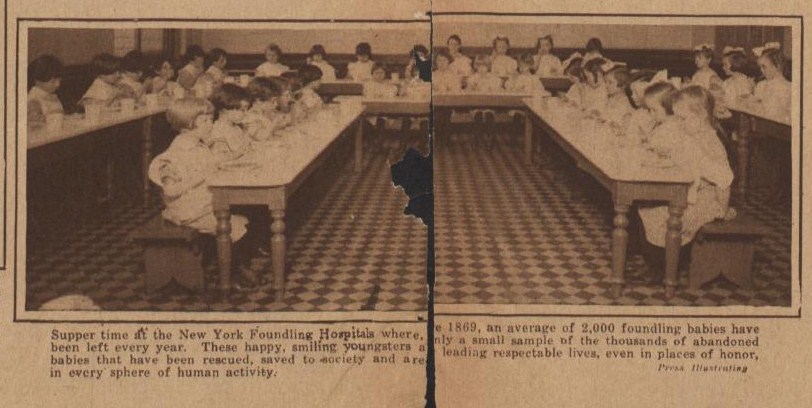

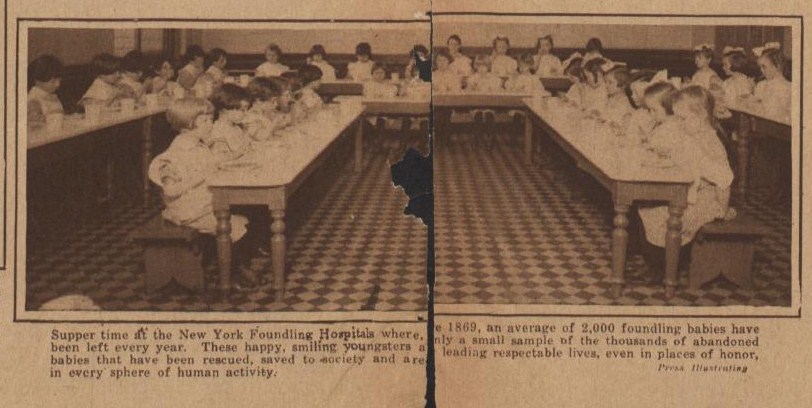

The December 28, 1919 issue of the New York Tribune pictured an institution founded in 1869 that was still going strong fifty years later:

feeding and forming foundlings

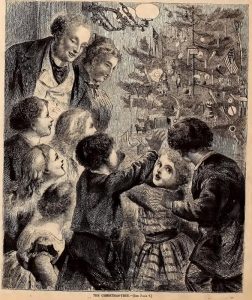

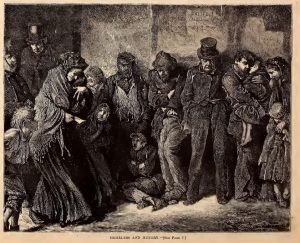

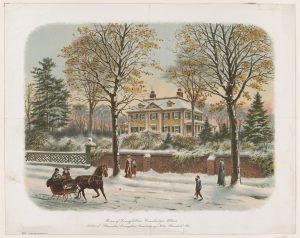

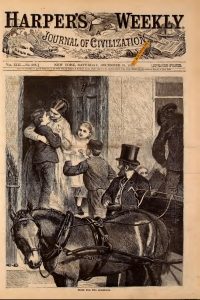

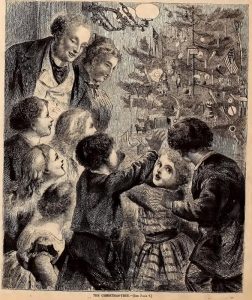

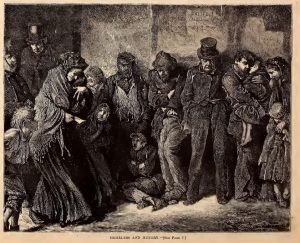

Here’s how Harper’s Weekly pictured Christmas in 1869:

no place like it

flag-festooned

wonder and awe

from real life

Those old Harper’s Weeklies are available at the Internet Archive – 1869 and 1870. According to page 7 in 1870, placing gifts around the Christmas tree was becoming more prevalent as fireplaces were being replaced with more modern heating mechanisms – Santa Clause wasn’t finding stockings hung at the fireplace as much. The street scene was based on real homeless and hungry people gathered at a London police station in search for food and shelter. Harper’s said there was now thousands in the same dire situation in America and urged some Christian charity to alleviate the suffering and to acknowledge “the Divine Master’s saying: ‘The poor ye have always with you.'”

American Battlefield Trust provides more details about the background of “Christmas Bells” and shows a photograph of the wounded Charles. You can read much more about Charles Appleton Longfellow at the National Park Service. Henry helped nurse his son back to health in the summer of 1863 after Charley was stricken with “Camp Fever”.

You can read the entire April 1906 issue of Mother Earth at Project Gutenberg. The same issue includes an article by anarchist and publisher Emma Goldman and “M.B.” about their travels in the northeast. What they have to say about Syracuse, New York sounds so modern, especially the dislike of coal:

The city where the trains run through the streets. With Tolstoy, one feels that civilization is a crime and a mistake, when one sees nerve-wrecking machines running through the streets, poisoning the atmosphere with soft coal smoke.

What! Anarchists within the walls of Syracuse? O horror! The newspapers reported of special session at City Hall, how to meet the terrible calamity.

Well, Syracuse still stands on its old site. The second meeting, attended largely by “genuine” Americans, brought by curiosity perhaps, was very successful. We were assured that the lecture made a splendid impression, which led us to think that we probably were guilty of some foolishness, as the Greek philosopher, when his lectures were applauded, would turn to his hearers and ask, “Gentlemen, have I committed some folly?”

The image of the Foundling Hospital was published in the December 28, 1919 issue of the New York Tribune, available at the Library of Congress. According to The New York Foundling three Sisters of Charity did indeed open the doors in 1869. Over the years some of the services have changed, but the organization continues “to share our founders’ belief that no one should ever be abandoned, and that all children deserve the right to grow up in loving and stable environments.” One of the three founders was Sister Mary Irene FitzGibbon. The photograph of Sister Irene and her charges is at the Wikipedia link and is part of a group at the Library of Congress by Jacob A. Riis called Poverty and tenement life in New York City, ca. 1890

“Sister Irene and her flock”

Elizabeth Blackwell

O Pioneer!

The December 28, 1919 Trib also reported the deportation of Emma Goldman and 248 other alien anarchists on the “Soviet Ark,” the U.S. transport Buford. The December 22, 1919 issue of The New York Times reported that the ship was bound for Kronstadt and headlined that “Emma Goldman Shows Bravado—Glad to Go, She Says, Predicting Triumphant Return.” Like Mahatma Gandhi, Ms. Goldman was born 150 years ago in 1869.

The quote attributed to Charles A. Beard didn’t specifically mention a personal, Christian God. Mr. Beard was an early 20th century historian who interpreted history through an economic lens. Writing with his wife Mary Ritter Beard, he saw the Civil War primarily as the result of class conflict: “The Beards downplayed slavery, abolitionism, and issues of morality. They ignored constitutional issues of states rights and even ignored American nationalism as the force that finally led to victory in the war. Indeed, the ferocious combat itself was passed over as merely an ephemeral event. … The Beards announced that the Civil War was really a “social cataclysm in which the capitalists, laborers, and farmers of the North and West drove from power in the national government the planting aristocracy of the South”. In their History of the United States (at Project Gutenberg) the Beards staed that bells and cannon worked together when South Carolina seceded: “As arranged, the convention of South Carolina assembled in December and without a dissenting voice passed the ordinance of secession withdrawing from the union. Bells were rung exultantly, the roar of cannon carried the news to outlying counties, fireworks lighted up the heavens, and champagne flowed. The crisis so long expected had come at last; even the conservatives who had prayed that they might escape the dreadful crash greeted it with a sigh of relief.”

Russian-born anarchist and feminist

it’s the economic conflict

Mary Ritter Beard

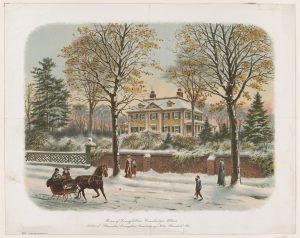

More from the Library of Congress: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s home in Cambridge, Mass; the poet sitting on a bench; portrait of Elizabeth Blackwell; the Confederate envelope; more portraits – Emma Goldman on a street car, Charles A. Beard, and his wife, Mary Ritter Beard, who was also a “a member of the Executive Committee of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage.”

Hal Jespersen’s map of the Mine Run campaign is licensed by Creative Commons – Hal Jespersen, www.CWmaps.com/. Amanda Foreman’s reference for the letter she quoted: “Columbia University, Blackwell MSS, Elizabeth Blackwell to Barbara Bodichon, May 25, 1865.” As of December 19, 2019 the New York State historical marker honoring Elizabeth Blackwell stood on South Main Street in Geneva, New York.

Daniel Russell quoted Charles A. Beard in a meditation about “Veiled Meanings,” in which he begins by considering the boy who chased arrows for Jonathan and David in 1 Samuel 20 and then goes on to say: “We all live in two worlds. One is the world of daily tasks where day by day we chase our arrows. But folded around that world is the world of the divine purpose.”

![Merry Christmas (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St., [1876])](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/09454v.jpg)

Hope it’s merry, “wild and sweet”

![Merry Christmas (New York : Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St., [1876])](https://www.bluegrayreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/09454v.jpg)