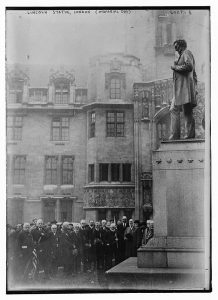

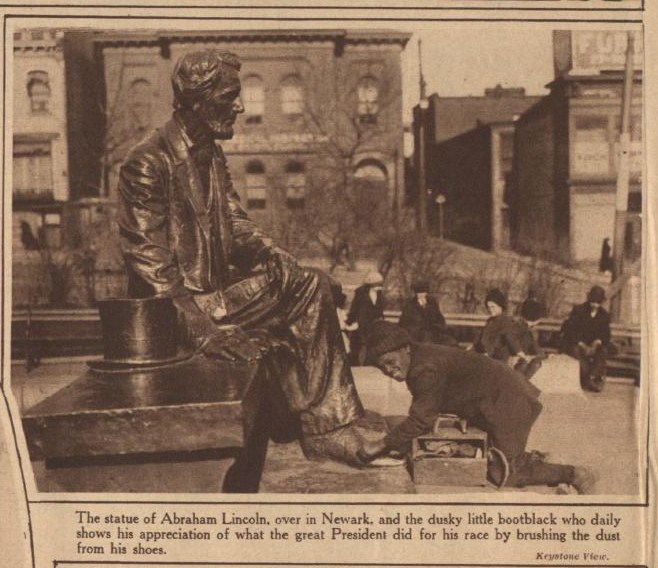

In the fall of 1917 a bit of a brouhaha broke out in the United States over Abraham Lincoln, or at least over his likeness. In 1913, to commemorate one hundred years of peace between the cousins, British-American Centenary Committee planned on building a statue of Abraham Lincoln in London. The statue was to be a replica of one by Augustus Saint-Gaudens that stood in Chicago’s Lincoln Park. The big war breaking out in Europe put the project on hold. In 1917 Charles P. Taft offered to pay for a different Lincoln statue to be erected in London. That statue would be a duplicate of one in Cincinnati by George Grey Barnard. Many people, including President Lincoln’s son Robert Todd, objected to that particular work being used for the commemoration. They found it too crass, too undignified, too un-presidential. Besides, did Abraham Lincoln really look like that with such extreme extremities – huge hands and feet?

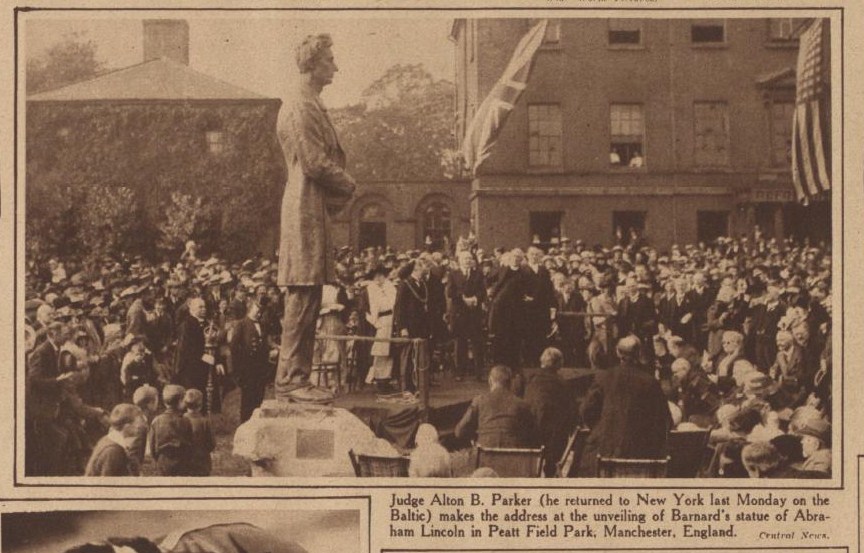

The peace centenary committee must have worked out a diplomatic solution. According to the October 5, 1919 issue of the New York Tribune Mr. Barnard’s uncouth Lincoln was relegated to Manchester in England and dedicated that September:

Irish-born journalist William Howard Russell actually met Abraham Lincoln at the White House. From his diary entry for March 27, 1861:

Soon afterwards there entered, with a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait, a tall, lank, lean man, considerably over six feet in height, with stooping shoulders, long pendulous arms terminating in hands of extraordinary dimensions, which, however, were far exceeded in proportion by his feet. He was dressed in an ill-fitting, wrinkled suit of black, which put one in mind of an undertaker’s uniform at a funeral; round his neck a rope of black silk was knotted in a large bulb, with flying ends projecting beyond the collar of his coat; his turned-down shirt-collar disclosed a sinewy muscular yellow neck, and above that, nestling in a great black mass of hair, bristling and compact like a ruff of mourning pins, rose the strange quaint face and head, covered with its thatch of wild republican hair, of President Lincoln. The impression produced by the size of his extremities, and by his flapping and wide projecting ears, may be removed by the appearance of kindliness, sagacity, and the awkward bonhommie of his face; the mouth is absolutely prodigious; the lips, straggling and extending almost from one line of black beard to the other, are only kept in order by two deep furrows from the nostril to the chin; the nose itself — a prominent organ — stands out from the face, with an inquiring, anxious air, as though it were sniffing for some good thing in the wind; the eyes dark, full, and deeply set, are penetrating, but full of an expression which almost amounts to tenderness; and above them projects the shaggy brow, running into the small hard frontal space, the development of which can scarcely be estimated accurately, owing to the irregular flocks of thick hair carelessly brushed across it. One would say that, although the mouth was made to enjoy a joke, it could also utter the severest sentence which the head could dictate, but that Mr. Lincoln would be ever more willing to temper justice with mercy, and to enjoy what he considers the amenities of life, than to take a harsh view of men’s nature and of the world, and to estimate things in an ascetic or puritan spirit. A person who met Mr. Lincoln in the street would not take him to be what — according to the usages of European society — is called a “gentleman;” and, indeed, since I came to the United States, I have heard more disparaging allusions made by Americans to him on that account than I could have expected among simple republicans, where all should be equals; but, at the same time, it would not be possible for the most indifferent observer to pass him in the street without notice.

As he advanced through the room, he evidently controlled a desire to shake hands all round with everybody, and smiled good-humoredly till he was suddenly brought up by the staid deportment of Mr. Seward, and by the profound diplomatic bows of the Chevalier Bertinatti. …