Right from the get-go there were issues with President Ulysses S. Grant’s cabinet. Six months later there was another problem – Grant’s trusted aide, confidant, and Secretary of War, John A. Rawlins died after a long bout with tuberculosis.

From the September 25, 1869 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

GENERAL JOHN A. RAWLINS.

GENERAL JOHN A. RAWLINS, late Secretary of War, died on the afternoon of September 6. The loss to the country will not be easily repaired; that sustained by the President is totally irreparable, for the latter has not only been deprived of a faithful servant, but also of a trusted friend.

JOHN A. RAWLINS was born in Jo Daviess County, Illinois, February 13, 1831. At his death, therefore, he was in his thirty-ninth year. He received a common-school and academic education, and until twenty-three years of age was engaged in agricultural pursuits. In 1853 he entered the law-office of J.P. STEPHENS, of Galena, where he made the acquaintance of President GRANT. In 1854 he was admitted to the bar, and was afterwards tolerably successful in his profession.

Previous to the war General RAWLINS’S career was comparatively obscure, but he had that strength of character and sturdy patriotism which, in the new era that opened in 1861, made him a prominent soldier. From the beginning of the war his record is closely associated with that of General GRANT. Soon after the fight at Sumter a large public meeting was held at Galena at which GRANT presided, and RAWLINS spoke. The latter had been known as a Democrat, and his declaration in favor of coercive measures to maintain the Union had on that account a greater effect.

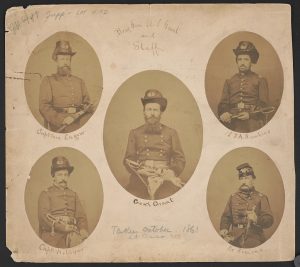

In August, 1861, he was a Major in the Forty-fifth Illinois, known as the lead-mine regiment; but at the request of GRANT, then a Brigadier-General, he received an appointment as Assistant Adjutant-General, and was assigned to the officer at whose request the appointment was given. From that time he accompanied General GRANT on all his campaigns.

He was made a Lieuteuant-Colonel November 1, 1862, and a Brigadier-General of Volunteers August 11, 1863. He was first appointed Chief-of-Staff to General Grant in November, 1862, and retained this position after the elevation of the latter to the rank of Lieutenant-General. On March 3, 1865, he was confirmed Brevet Major-General. His faithful services as Chief-of-Staff were fully appreciated by General GRANT, who in no small degree owed his remarkable success to General RAWLINS.

For a short time after General Grant’s inauguration General SCHOFIELD remained at the head of the War Department. But the President decided to appoint General RAWLINS to that place in his Cabinet, and finally prevailed upon him to accept it. He was unanimously confirmed, and his appointment was satisfactory both to Republicans and Democrats. Under his charge the affairs of the army have been conducted with increased efficiency, and with a wise economy of expenditure.

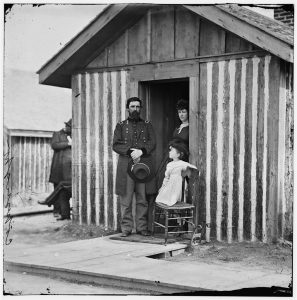

General RAWLINS was a victim of consumption, a malady contracted bt exposure during the war. His private character was such as to win the esteem and affection of all who knew him. His temper was equable, and his domestic relations were of the most pleasant nature. His first wife, whom he married June, 1856, died in 1861. In December, 1863, he married Miss MARY E. HURLBURT of Danbury, Connecticut. This lady, who survives him, is herself an invalid.

In the same issue Harper’s gave President Grant some advice about picking a successor:

GENERAL RAWLINS.

The great assent of the country to the words of Attorney-General HOAR’S touching message, in speaking of General RAWLINS – “a man so upright, able, and faithful” – shows how deep is the public sense of his loss. It shows also the sagacity of the President’s course in selecting for so important a position a man with whose character and capacity he was thoroughly satisfied, although his name might not be familiar to the public. From the beginning of the war intimately associated with General GRANT, General RAWLINS constantly proved his ability; and the testimony of all who knew best, since his accession to the War Department, proves the vigor and sagacity with which, even in his extreme ill health, it was conducted by the Secretary. Had he been a conspicuous politician, is it likely that he would have been a better officer, or that the country would more truly mourn his death?

In selecting his successor we hope the President will look among those that he knows rather than those whom the politicians expect or present. We understand the necessity of party sympathy and support, and we also insist that it is the duty of every man to be a politician, so far as that word implies a knowledge of the principles involved in the questions upon which he votes. But the word politician has come to mean the hucksters in politics, the doers of dirty work claiming to be the party, and in that sense we use it. General Rawlins could not have been the candidate of the politicians; but the party that supported General Grant, as well as the country at large, were satisfied with his appointment. They will be equally pleased with a successor whom upon his appointment they may not know, if his administration of the office shows them, as in the case of General RAWLINS, that the President has selected a man “upright, able, and faithful.”

Wikipedia points out that John Aaron Rawlins was certainly faithful to the Union. At a Galena town meeting after Fort Sumter he said, “I have been a Democrat all my life; but this is no longer a question of politics; It is simply country or no country; I have favored every honorable compromise; but the day for compromise is passed; only one course is left us. We will stand by the flag of our country, and appeal to the god of battles.” (NY Times September 7, 1869)

His loyalty to Ulysses S. Grant included doing his best to keep the general away from alcohol. James M. McPherson has written, “… a hard substratum of truth about Grant’s drinking remains. He may have been an alcoholic in the medical meaning of that term. He was a binge drinker. For months he could go without liquor, but if he once imbibed it was hard for him to stop. His wife and his chief of staff John A. Rawlins were his best protectors. With their help, Grant stayed on the wagon nearly all the time during the war. If he did get drunk (and this is much disputed by historians) it never happened at a time crucial to military operation.”[1]

According to documentation at archive.org the 45th Illinois remembered its first major at its reunion on September 28, 1869:

John A. Rawlins “was originally buried in a friend’s vault in Congressional Cemetery in Washington. He was subsequently moved to Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery.”

In the short term President Grant followed Harper’s advice. He appointed another long-time associate, General William T. Sherman, as on one month interim Secretary of War.

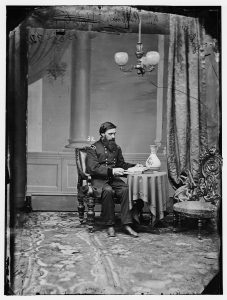

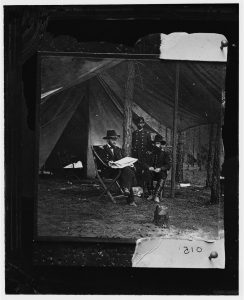

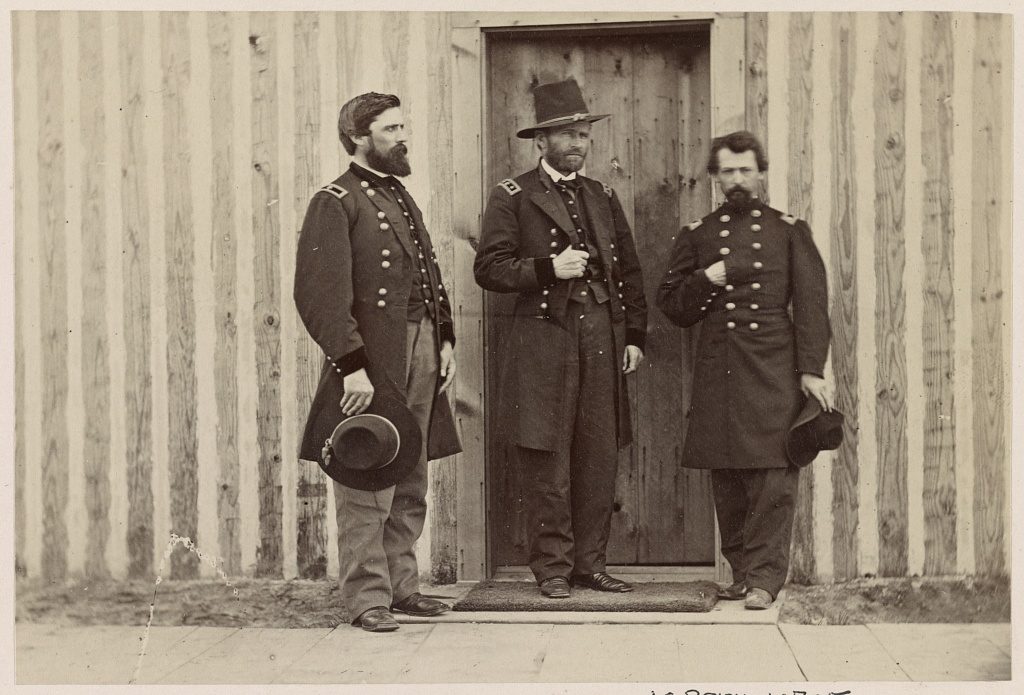

All the material from Harper’s Weekly 1869 is available at the Internet Archive. From the Library of Congress: the study; Grant’s upper left-hand man “taken October 1861 at Cairo Ill” ; Grant, Bowers, and Rawlins at Cold Harbor; with family at his City Point quarters; still at City Point with Grant and Bowers; statue in Washington, D.C.

- [1]McPherson, James M. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989. Print. pages 588-589.↩