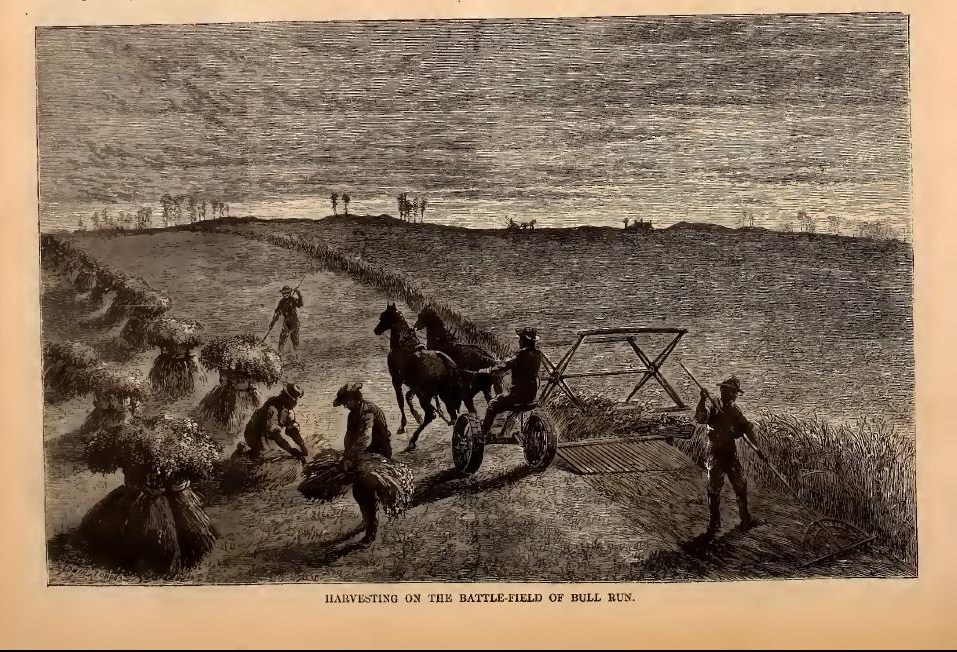

A recent post was about a medallion and monument related to the American Civil War that was found on a single page in a newspaper from 150 years ago. And, mirabile dictu, the editors at Harper’s Weekly packed even more blue-gray matter onto the very same page! The paper looked at a picture of a grain harvest in Virginia and saw something like a symbol of national regeneration.

From the August 21, 1869 issue of Harper’s Weekly:

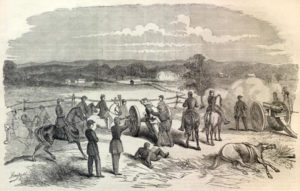

HARVESTING ON THE BATTLEFIELD OF BULL RUN.

How rapidly the wounds of war are healed! Half a million of men are swept from the earth by a civil war; but before a grateful people have done writing their epitaphs their places are more than filled, and the census scarcely notes the increase of mortality on their account.

Eight years have passed since the battle of Bull Run, and to-day there is left scarcely a trace of this early conflict of the war. Where the youth of the North and of the South met in array of battle eight years ago, there to-day the farmers are harvesting the cereals of August. The field that was red with blood is yellow with grain. And now the improvements of agriculture are illustrated upon the arena where then a feudal system of labor arrayed its boastful champions.

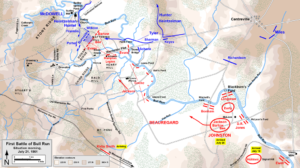

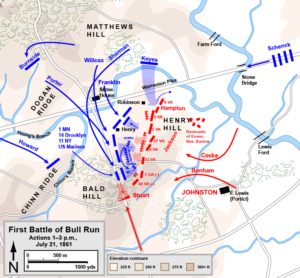

There were two Civil War battles on the Bull Run or Manassas site. The first, on July 21, 1861, was the first major battle in the war. Although Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, in response to the rebel bombardment and capture of Fort Sumter, proposed his “Anaconda Plan” – a slow, methodical squeeze on the South and capture of its territory, there was a lot of political pressure in the North for the Union army to take it to the rebels right away. At the White House on June 29th Union commander Irwin McDowell wanted more time to train his new recruits. President Abraham reportedly ordered General McDowell to begin the offensive with these words: “You are green, it is true, but they are green, also; you are all green alike.”[1]

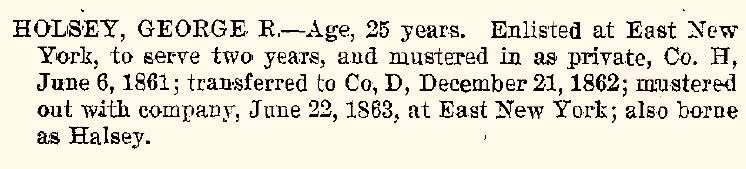

It would seem that New York’s 38th Infantry Regiment was certainly green. The two year regiment didn’t leave for the Washington, D.C. area until June 19th. On July 7th “it was ordered to Alexandria and assigned to the 2nd brigade, 3d division, Army of Northeastern Virginia, and was active at the first battle of Bull Run, where it lost 128 in killed, wounded and missing.”

About ten days after the battle a member of the 38th wrote home. The soldiers who survived were a lot less green. From a Seneca County, New York newspaper (probably) published on August 15, 1861:

From a Seneca Falls Boy in the Battle of Bull’s Run.

The writer of the following letter is the eldest son of Mr. HILDRETH HALSEY of the Town:

Headquarters 38 REGT, CAMP SCOTT, Co. H,

Washington, D.C., July 31, 1861.

Dear Father and Mother: – I wrote you a few lines Tuesday, on our return from the battle-field, but suppose you have not got them yet. I begin to feel a little like myself now, although I am stiff and sore yet; but will attempt to give you an account of our movements and of the battle, as correct as I can. I will commence at Centreville, from which place we started for the battle-field.

We were all aroused from our slumbers at 12 o’clock on Saturday night and held in readiness until daylight Sunday morning, when we started on the march for Manassas or Bull run, which are in fact all one. We reached there about noon, after marching fifteen miles, and wading muddy streams up to our waists, without having anything to eat since six o’clock Saturday afternoon, save a few hard sea biscuits, which were not very palatable, but had they been ever so good we could not have taken time to eat them.

Just before we entered the field we threw off our blankets, haversacks and jackets, and marched into the field in our shirt sleeves, in a body of five thousand men, which consisted of the whole of the Second Brigade, under command of Col. Wilcox, acting under Brigadier General McDowell. There was only one Regiment on the field before us, and they laid down under the hills, entirely out of sight of the enemy. I believe they fired two shots at random into the woods and then retreated. I do not know what Regiment it was but think it was one from Pennsylvania. Our entire Brigade then received orders to advance on the enemy, which we did on quick time. The enemy then began to fire into us from their masked batteries with terrific force, but fortunately we were so far advanced that the balls passed over our heads, many of them falling into the ranks of different Regiments in the rear of us, killing many of them. At this time we were about half a mile in advance of our battery. The enemy then emerged from the woods and “let sliver” at us with great power. We then retreated and our battery advanced in front of us and fired into the Rebel batteries with powerful force but I think without much avail, as they were too numerous and most of them built of stone and railroad iron, which were almost impenetrable.

The enemy soon got range of our battery and fired into it with such force that they soon killed some of our artillerymen and horses, and broke the wheels of some of our best gun-carriages. Then the Rebels, or what is called the Black Horse Cavalry, rushed out of the woods to take our battery, which they failed to do. During this bombardment we laid just over the point of the hill, and when they attempted to take our battery, we gave them such a shower of bullets, that only three out of sixty retreated, all the rest being killed. We kept them back for about half an hour, when they again rushed upon us with such a powerful body of men that we were obliged to retreat for the last time. The order was then given for a general retreat, which was executed as fast as possible, but when we had got about four miles from the battle-field we were partially headed off by the Rebels, who fired into us with tremendous force, killing many and taking a great many prisoners. The greatest confusion prevailed at this time; those who were scarcely able to walk, at once started at the top of their speed and scattered through the woods in all directions. Many of the wounded jumped from the ambulances and wagons and fled to the woods for refuge.

I notice that the papers foot up the loss of Federal troops at about six hundred, which I am pained to say is too low an estimate, as I am sure the loss will not fall short of 1,000 to 1,500 killed. As to the Rebel loss I can only say that is great. They laid, in many places, like bundles of wheat in the harvest-field.There were from 40 to 60 killed in our Regiment and a great many wounded. Our whole force in the field did not number over 25,000 men, while that of the enemy it is said numbered from 50,000 to 60,000. So you see we stood rather a poor chance to win the battle.

I was in the hottest of the battle a little over three hours and escaped without even a scratch while those who stood by my side were shot and instantly killed. I was not the least frightened after we had fired the first shot until we had left the field and reached our old quarters near Alexandria. And then to think of what we had passed through during forty-eight hours seems almost incredible, yet it is true. From the time we started from Centreville, until we returned here we marched sixty miles, without a moment’s rest or anything to eat except a few hard sea-biscuit. We suffered more from want of water than victuals. All that we had was what we could dip up out of a mud-puddle along the road. If anybody had told me what I had to pass through, before I started, my first thought would have been that I never could endure it, but as the old saying is, we don’t know what we can endure until we try.

I could write a great deal more, but have not time at present, as I have got to turn out to drill soon. I have only to say that I feel thankful to God for the preservation of my life through the late battle, and hope that it will be spared through all battles to come, until such time as we may all see the Stars and Stripes float all over the United States.

Truly yours,

GEO. R. HALSEY

P.S. – I picked up a beautiful sword on the battle-field, worth about $25.

First Bull run is also famous for the greenness of some Northern civilians. Many Washingtonians, including some United States Senators drove their carriages out for a look at the great battle and brought their picnic lunches. The dinner theater became interactive. The American Battlefield Trust explains that most of the spectators stayed well away from the actual fighting, but many of them got caught up in the mass stampede of retreating Union soldiers. None of the spectators from Washington were wounded, although Congressman Alfred Ely was captured and confined in Richmond’s Libby Prison for about five months. “Only one civilian was killed in the battle, the aged widow Judith Henry whose home was engulfed by the fighting.”

One young man from Boston, not part of the capital throng, apparently got much nearer the actual battle. According to documentation at Project Gutenberg Edward Henry Clement recounted the adventure of his brother, Andrew J. Clement, at a March 1909 meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Andrew had written up a “little paper” about his adventure years before his death in 1908:

THE BULL-RUN MUSKET.

A single dead soldier of the Union army was an object of intense public interest up to the date of the battle of Bull Run in July, 1861.

_____________

There were two lads of us who left Boston to visit our brothers—both of whom were in the army and in the same company. We expected to find the Army at Washington; and we each carried a box of dainties to delight our brothers with. On reaching Washington, we were sorely disappointed to find that the army had started on its march to Richmond; and that no civilians were allowed to follow—not even to cross the Potomac into Virginia. So there was nothing to do but see the sights in Washington and return to our homes. But we had been there only two days when the news came of a fight or skirmish on July 18th at Blackburn’s Ford, where several were killed, and one of the dead was the brother of my companion. It was a terrible blow to my friend, and a great shock for me.

We immediately telegraphed home, and at once came the reply “Get the body, if you can, and send it home.” Well, we two lads went to the War Department and I suppose our sorrowful tale moved them with compassion, for they gave each of us a pass to go to the front to get the body of the dead soldier. I’ve got that pass stowed away now, among my papers, as a War curiosity. It reads,

Allow the bearer, Mr. Andrew J. Clement, to pass the lines and go to the Front for the body of a friend.

DRAKE DE KAY

Aid de Camp.

Later in the war, the death of a soldier was of too little importance to awaken such sympathy at Headquarters. Indeed, two days later, there were thousands killed within two miles of the spot where those killed in this skirmish were buried. After much difficulty, we hired a light wagon in which my friend rode, while I got a seat in an army wagon that was taking out supplies. It was just midnight on Saturday July 20th when we started from Willard’s Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue. There was a full moon, and the night was lovely. I was all excitement. I was going to join the army. I should see my brother, and perhaps I should see the big battle everybody was talking about as soon to be fought.

Well, I saw all that I expected to see and a good deal more. As the horses toiled painfully all that night over the rough and hilly roads, I little thought that on the very next night I should be more painfully trudging back over that very route footsore and weary, a gun on my shoulder—and ready to fight if the victorious enemy came up with us. Yet such was the case, and the gun in the hall is the one that I carried to Washington after the battle of Bull Run, July 21st, 1861.

Of course the ride that beautiful night was too exciting for sleep. It was just after daybreak, when we were taking a hasty breakfast at a small tavern, that we heard the first boom of a heavy gun. This was the gun that opened the great battle of Bull Run. We were yet six miles away from the army—and all were impatient to reach our destination. The horses were kept at their best working pace, and when we had gone three miles we met troops marching towards us. These were certain regiments that wouldn’t fight because the ninety days of their term of service had just expired. They looked thoroughly ashamed of themselves, and marched in great disorder. The officer with our wagon, and the soldier who drove it, both scoffed at them and called them sneaks and cowards; and, cowards as they were, they didn’t resent the insults. For myself, I felt as though they all deserved shooting when they got to Washington.

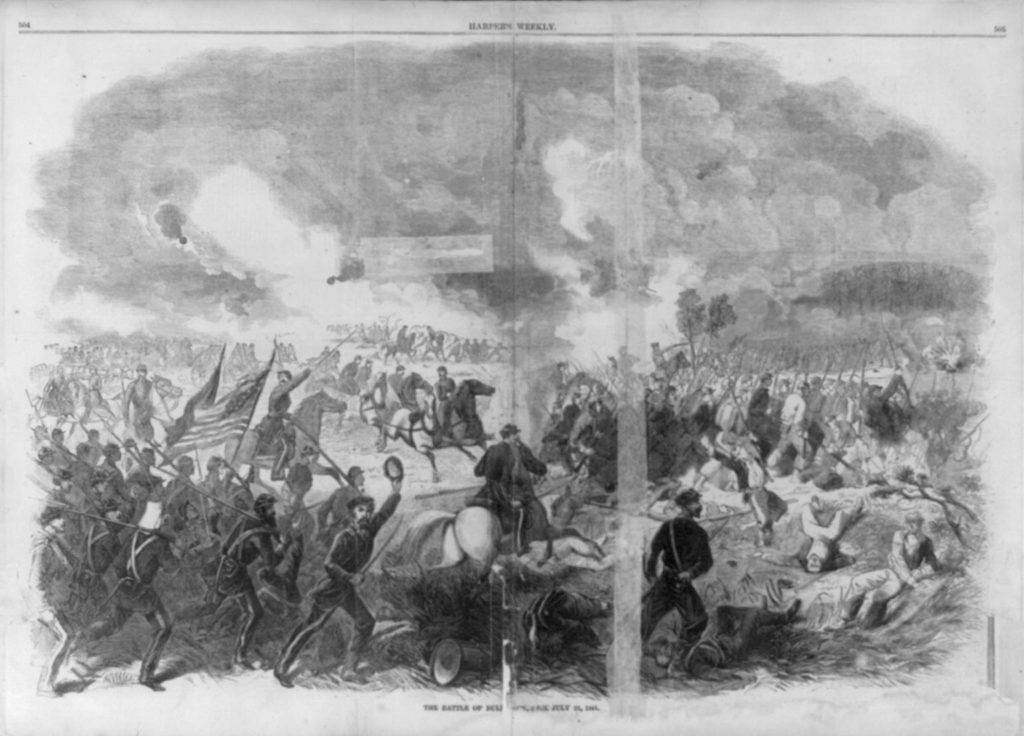

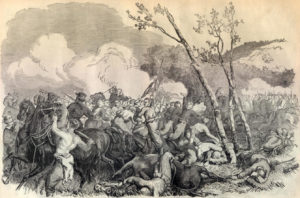

GALLANT CHARGE OF THE SIXTY-NINTH REGIMENT, NEW YORK STATE MILITIA, UPON A REBEL BATTERY AT THE BATTLE OF BULL RUN.

An hour later we reached Centreville and looked down on the battle-field. Hastily finding where my friend’s dead brother was buried, I left him to his mournful task of recovering the corpse while I went to find my own brother whom I yet hoped to meet alive. But it wasn’t an easy task. The line of battle was long; and, in spite of my inquiries, I went wrong. I went to the right wing only to find that the regiment I sought was probably away off on the left wing. Nobody seemed able to give exact information, and everybody wanted to know what a boy in black clothes and a straw hat was doing on the battle-field. Once I went up and sat down in the rear of a battery of light artillery to watch the effect of the firing, and the Capt. drove me off with terrible oaths. But I went around a small farm house and crept back again, and saw the grapeshot scatter the “rebs.” And so I went on from point to point, staring and asking questions, and being stared at and questioned in return. At length I learned that the regiment I wanted was at the extreme left. So off I started, already weary from loss of sleep, excitement and tramping under the hot sun.

Arriving at the left, I again was attracted by a battery in action, and it was while I stood entranced with excitement that my brother discovered me. His regiment was lying in the bush close by supporting this very battery. Never was a man more surprised than was he at that moment. He supposed I was at home in Boston. But, before he would talk, he made me go into the woods and lie down with the soldiers so as to be in less danger. And there I crawled around and shook hands with nearly a hundred men whom I had known all my life. Many were the questions I answered, and scores of messages were given me to take home to parents and friends. The boys seemed very sad—for a member had been killed in this company only three days before, and they expected to be actively fighting again at any moment. At length my brother insisted that I should go back to Centreville out of danger, and I started with a heavy heart. But secretly I resolved to try to go to Richmond with the army, for I felt sure it would only take a few days. Up to that time it seemed to be victory for us; and I didn’t believe it could possibly be otherwise. So I went back to Centreville. I was very hungry as well as tired. It was now past four o’clock in the afternoon.

______________

I soon found a group of sick officers who were about to dine off of boiled beef close by the army wagon in which I had come from Washington. They asked me to join them. I had just got fairly seated when the astounding news came that our army was defeated and was retreating. I didn’t believe it; but I rushed to the hilltop to see for myself. Down there on the plain, where I had been in the morning, there was certainly much dust and confusion. Just then fresh troops, the reserves, started to go down, but even to my inexperienced eye it was plain that they went in bad order and went too late. It was there that I saw the general who wore two hats—one crushed over the other—and who was reported in newspaper accounts of the scene as being very drunk that day. He certainly appeared decidedly drunk at that moment.

Wild with excitement, I rushed down hill too; but long before I got where I had been a few hours before, I met the rush of panic stricken men coming pell-mell from the field. To resist this rush was impossible and worse than useless. Wagons driven at full speed came with the men. Shouted curses filled the air. Wagons broke down, and, cutting the harnesses, men mounted the horses and rode off toward Centreville. Muskets were thrown away and filled the road for a long distance. It was there that I picked up my gun, begged a pocket full of ammunition, and resolved to do my share when the terrible Black Horse Cavalry reached us—for it was reported that they were coming at full speed. Ere long I reached Centreville again, and left the rush to look for my wagon. It had gone, long before, in the grand stampede for Washington. That didn’t worry me much then—I thought I would find my brother again; and fight in company with the boys I grew up with. So I waited and waited at Centreville till the sun got low. I saw at length that it would be useless to try to find anybody. There were several roads; and all were full of disorganized troops.

But the first mad rush was over. All the army did not run. I did not run a step. It was nearly sunset when I left Centreville; and, as I was terribly hungry, I stopped, after going about a mile, and joined two of N. Y. 69th regiment who were having a regular feast out of a broken down and abandoned sutler’s wagon. I remember that I ate a whole can of roast chicken and many sweet biscuits, and washed the whole down with some sherry wine drank from the bottle—my first experience in wine drinking.

Much refreshed, I took up my musket and started for Washington with an oddly mixed crowd of gay militia uniforms representing parts of many regiments. Yet there were still behind us good, orderly, full regiments, that stayed in Centreville till after midnight and came into Washington late the next day in fine marching order. They did not run, and my brother’s regiment was one of them. It was 10 p. m. when I reached Fairfax Court House. There I rested, sitting on a rail fence, as a motley crowd poured by, each squad saying that the Black Horse Cavalry was coming. So I clung to my musket, though my shoulders began to get a little sore. It was after midnight when I started again. The night was very dark, for heavy clouds obscured the moon. The road, very rough in itself, was now full of materials thrown out of wagons. There were shovels, pickaxes, boxes, barrels, iron mess-kettles, muskets, knapsacks, and all sorts of litter that soldiers could throw away, and over these and the loose stones of the rough road we stumbled in the dark, amid choking dust, and up and down the long rolling hills that the army marched over so often afterwards during that terrible war. Still, I well remember that it seemed to me a sort of wild picnic; and I would clutch my gun and feel of my cartridges in a very determined mood to defend Washington to the death.

Wearily the night wore on; and steadily I tramped, talking in the dark, from time to time, with strangers—men from all parts of the Union whom I didn’t see then and probably never saw afterwards. Bad as it was to march in the dust, it was still worse when it began to rain just before daybreak. Gently it came at first; and slowly the dust became a thick paste of slippery mud. Steadily the storm increased till it became a downpour. I had on a thin black summer suit, a straw hat, and a pair of low-cut thin shoes and white stockings. When day broke we were a bedraggled, thoroughly soaked, mud-stained party. Of all that vast crowd probably I presented the worst appearance, for I was the only citizen in that section of the crowd. I bantered jokes with such as were in joking mood, but most of the crowd were now silent and weary. All along the road lay men asleep in the pouring rain. There were blood blisters on my feet, but never once did I stop except to get a drink of water at a brook just after daylight. The rain now fell in torrents; we were literally wading in mud and water.

The thirty miles from Centreville to Washington seemed three times that distance. My gun grew more and more heavy, and I shifted it constantly. It was about ten o’clock Monday forenoon when I reached the Virginia end of Long Bridge. A strong guard was posted there to stop the troops; for Washington was already full of fugitive soldiers. Forcing my way through a vast mob of shouting, cursing soldiers, I reached the officer in charge, and got a rough reception. First he doubted my pass; next he wanted to take away my musket, but I protested that I had saved it from the enemy; and at length he allowed me to pass carrying the gun I had so honestly won. I went down Pennsylvania Avenue much stared at as I limped along. Reaching my hotel, I took a bath and turned into a good bed, thinking of my brother and the thousands of other soldiers who were out in the rain and many of whom would perhaps have no bed to turn into for three years; for there were a few three years regiments even then.

The next day, to my great joy, my brother’s regiment marched in and over to Georgetown heights; and, after visiting them there, I sent my gun home by Adams Ex. and took the train for Boston. Said my father, when I got home, “Well, I think you have got enough of war now.” “No, sir,” I said, and in less than thirty days I had enlisted; and three years from the date of the first battle of Bull Run I was skirmishing about six miles from Richmond—three years—and yet I hadn’t quite got to Richmond.

That Bull-Run musket is the only war weapon left in the family, and I hope you will keep it in memory of the good work I was willing to do with it, even before I was a soldier.

According to the report on the historical society’s meeting Andrew J. Clement served as First Sergeant, Company M, First Massachusetts Cavalry. Margaret Leech mentions Sergeant Clement in her Reveille in Washington: 1860-1865.

According to documentation at Wikipediathe Library of Congress, two years after the Massachusetts Historical meeting and fifty years after the first battle, it wasn’t war, it was peace at the Bull Run battlefield:

July 21, 1911 at Henry Farm, Confederate veteran and Virginia governor William Mann wearin’ the gray (jacket)

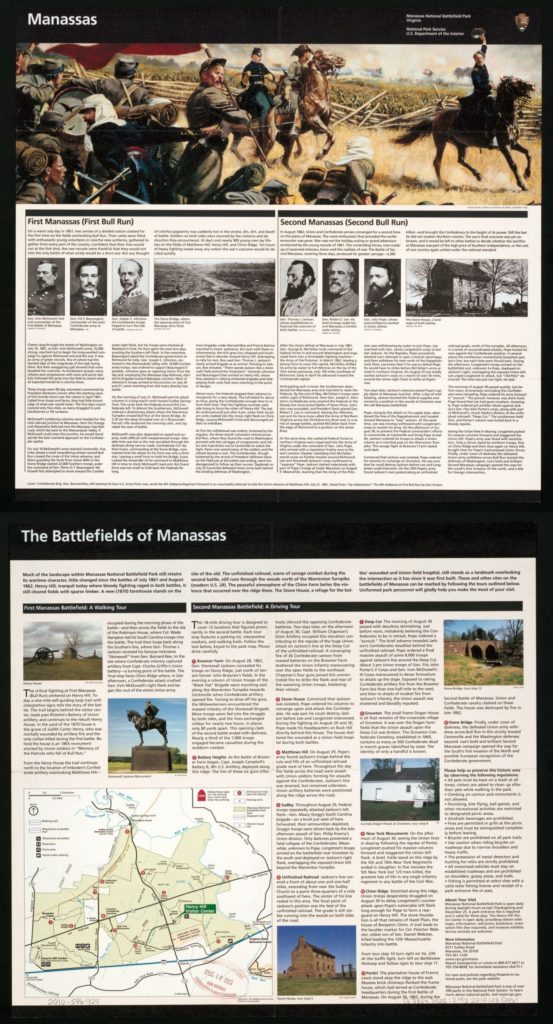

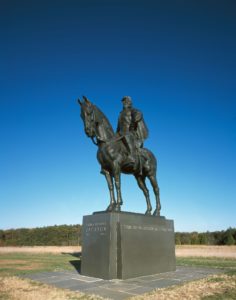

I don’t think there’s too much farming going on at the Bull Run battlefield these days. Since 1940 the site has been a national park. This post has mostly been about the first battle, but on August 30-September 1 this year the Manassas National Military Park is commemorating the 157th anniversary of Second Manassas. Besides the location and Confederate victory, Stonewall Jackson was common to both battles. His “steadfastness influenced the outcome of both battles.” (see brochure)

I first used the letter from George Halsey during the halcyon days of the American Civil War Sesquicentennial. Brigade commander Orlando B. Willcox would eventually receive the Medal of Honor for his conduct at First Bull Run. I found the letter at the Seneca Falls (NY) public library in one of several big loose leaf binders filled with newspaper clippings from the Civil War years.

You can find all the Harper’s Weekly from 1869 at the Internet Archive

The New York State Military Museum provides the rosters for the state Civil War units. And a whole lot more

The images of First Manassas (except for the top one) are from Harper’s Weekly August 3 and August 10, 1861. They are online at Son of the South.

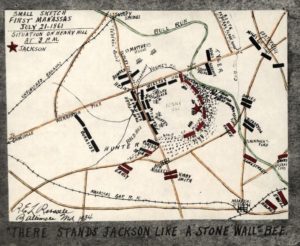

Hal Jespersen’s maps are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license: July 18th; July 21stmorning; July 21st early afternoon

From the Library of Congress: First Manassas at 2 PM, originally published in the August 10, 1861 issue of Harper’s Weekly; Robert E. L. Russell’s sketch of First Manassas at 3 PM; remains of Judith Henry’s house – the Organization of American Historians agrees; Carol M. Highsmith’s photo of Judith Henry’s gravesite – you can see more about it at Find A Grave; also from Carol M. Highsmith: cannon at the national park, Stonewall statue erected in 1938; Manassas National Battlefield Park brochure; Richmond celebration; Bartow monument (c1872), but according to Wikipedia, the white obelisk monument dedicated in September 1861 was stolen in 1862 (a smaller marker from 1936 still should be there); from the peace jubilee: registration, ex-Confederate W.C. Round, President Taft, ex-Confederate and Virginia governor William Mann center stage – the governor served in the 12th Virginia Infantry, which apparently didn’t take part in First Manassas, group shot of the vets; George N. Barnard’s photo near Sudley church from March 1862.

- [1]McPherson, James M. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989. Print. pages 335-336.↩