150 years ago a newspaper doubted the truth of what it called a “verdict of Science” regarding earth’s next-door neighbor. From Harper’s Weekly May 22, 1869:

THE MOON’S INFLUENCE

WHATEVER be the influence exercised upon the earth by the varying positions of the planets, it is unquestionable that a very important effect is produced upon our orb by the changes in the position of our satellite the moon. That tiny orb, a mere speck compared with the larger planets, nevertheless by its nearness exerts an influence upon earth far greater than that produced by all the planets collectively. In old times it was never doubted that the moon greatly affected the superficial condition of our planet – not only as regards the weather, but also by more subtle forms of action. The words “lunatic” and “moon-struck” still exist to show this old belief – indicating the real or supposed effect of the moon’s action upon the cerebral or nervous organs of man. And in many of the old, indeed still prevalent, weather-proverbs, the belief in the influence of the moon upon the atmospheric conditions of our planet is abundantly shown. In recent times, Science has strongly combated [sic] this old belief; and some years ago it was authoritatively declared, as the verdict of Science, that the moon had no effect upon the weather at all. Now, even judging á priori, yet upon purely scientific grounds, this verdict of the savans might have safely been pronounced a mistake. Since the moon powerfully affects the ocean, the vast expanse of water which covers the larger part of the earth’s surface, producing the striking phenomenon of the tides – can it be doubted that lunar action does not equally, nay to a much greater extent, affect the still more mobile ocean of air (the atmosphere) which covers the whole surface of our planet? And if the moon produces tides and currents in the atmosphere, must it not to an important degree affect the weather, which is so largely dependent upon the currents, movements, and disturbances in the atmosphere?

In truth, although the recent dictum of Science ignoring the old belief, and denying that the moon has any influence on the weather, has not yet been formally revoked, it is easy to see that savans begin to falter in their doctrine. And well they may. A whole host of facts are arrayed against them. Professor Pidmieri [Luigi Palmieri], who has so closely studied the varying phenomena of Vesuvius, declares that there is a perceptible relation between the phases of the moon and the developments of volcanic action. Any one, too, who has lived in the south, or even sailed on the Mediterranean, may have noticed how carefully sleepers in the open air guard their head and face against the rays of the moon; he may even have seen instances of the injurious consequences (in the form of ophthalmia and other ills) which attend the neglect of such precautions. In India it is well known that meat exposed to the moon-rays immediately putrefies. Some of these facts indicate a lunar action more subtle than Science can as yet account for. But the moon’s influence on the weather is perfectly intelligible – on this ground, if no other, that it produces and tides and currents in the atmosphere just as it does in the less mobile ocean.

The subtlety might have to do with finding the right tool to measure. It seems like a big part of Science is its instruments and how powerful/sensitive they are. In 1609 Galileo Galilei adopted and adapted a Dutch telescope. “While not being the only one to observe the Moon through a telescope, Galileo was the first to deduce the cause of the uneven waning as light occlusion from lunar mountains and craters. In his study, he also made topographical charts, estimating the heights of the mountains. The Moon was not what was long thought to have been a translucent and perfect sphere, as Aristotle claimed …”

Telescopes have become more and more powerful. In Through the Telescope (1906) James Baikie presented quite detailed images of the moon, and he also gave Galileo his due:

… The man to whom the human race owes a debt of gratitude in connection with any great invention is not necessarily he who, perhaps by mere accident, may stumble on the principle of it, but he who takes up the raw material of the invention and shows the full powers and possibilities which are latent in it. In the present case there is one such man to whom, beyond all question, we owe the telescope as a practical astronomical instrument, and that man is Galileo Galilei. He himself admits that it was only after hearing, in 1609, that a Dutchman had succeeded in making such an instrument, that he set himself to investigate the matter, and produced telescopes ranging from one magnifying but three diameters up to the one with a power of thirty-three with which he made his famous discoveries; but this fact cannot deprive the great Italian of the credit which is undoubtedly his due. Others may have anticipated him in theory, or even to a small extent in practice, but Galileo first gave to the world the telescope as an instrument of real value in research.

The telescope with which he made his great discoveries was constructed on a principle which, except in the case of binoculars, is now discarded. It consisted of a double convex lens converging the rays of light from a distant object, and of a double concave lens, intercepting the convergent rays before they reach a focus, and rendering them parallel again … . His largest instrument, as already mentioned, had a power of only thirty-three diameters, and the field of view was very small. A more powerful one can now be obtained for a few shillings, or constructed, one might almost say, for a few pence; yet, as Proctor has observed: ‘If we regard the absolute importance of the discoveries effected by different telescopes, few, perhaps, will rank higher than the little tube now lying in the Tribune of Galileo at Florence.’

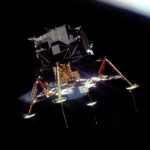

In his 1883 The Moon Reverend C.M. Westlake used evidence from the telescope to imagine traveling to and spending some time on the moon:

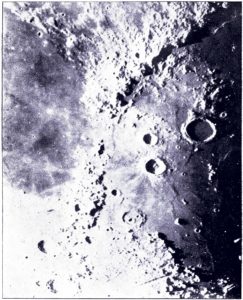

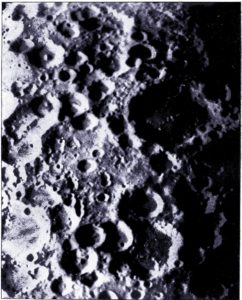

… It is quite probable as the moon looks to-day so will it appear to observers thousands of years hence. An ideal view of the moon-world and its phenomena may be pleasing and profitable. We pass no planets or stars in our journey to the moon; for it is the nearest of the larger heavenly bodies. In imagination we traverse the 240,000 miles of space and stand at sunrise upon one of the mountain tops of the moon. Over head is a cloudless sky, of inky blackness; the background of countless brilliant stars, and of the earth, which is in appearance equal to many moons, and, when passing between the sun and the moon, is like a dark sphere in a circle of glittering gold and rubies. From the dark horizon, the sun suddenly darts his dazzling beams upon the tops of the mountains; yet for a time leaving the flanks and valleys still wrapped in total night. In the absence of air and vapor there is no gradual transition of night into day; no penciling streaks, no gilding and glowing, which make earth’s sunrise so beautiful; yet there is increase of illumination as more and more of the sun’s disk becomes visible above the horizon. The light, with a motion twenty-eight times slower than upon the earth, creeps down the mountain side, across the plain, and into the fearful blackness of the yawning crater.

Look where we may, we see vast regions of the wildest volcanic desolation, in which the ground is honey-combed with countless round pits or craters, some of them of immense depth and upward of four miles in diameter. On our right are steep gorges and precipitous chasms of appalling depth and blackness, and on our left cliffs, crags, and peaks tower far above us. We gaze upon the debris of long since expired volcanoes, but look in vain for a single vestige of past or present organic life. “No heaths or mosses soften the sharp edges and hard surfaces, no tints of cryptogamous or lichenous vegetation give a complexion of life to the hard fire-worn countenance of the scene. The whole landscape, as far as the eye can reach, is a realization of a fearful dream of desolation and lifelessness ; not a dream of death, for that implies evidence of pre-existing life, but a vision of a world upon which the light of life has never dawned.” In the midst of this dreary, desolate grandeur we look in vain for oceans, lakes, or seas; we listen in vain for the hum of industry or the sounds of wind or water, where there is no life to break the stillness, no breeze to murmur, “no brook to plash, no ocean to boom and foam.” Let this desolate, craggy, motionless world be filled with the activities of our own; and, in the absence of air, which is the medium of communication with the organs of hearing, it would still be a realm of dead silence. In vain would lips quiver and tongues essay to speak. The rattle of drums, the crash of musketry, the thunder of a thousand cannons would produce no sound in that airless world. At the close of the moon’s long day we see, in glorious perfection, the red protuberances, crimson flame billows, corona and zodiacal light of the sun; as during the day we may have seen its spots and faculae. During the lunar night periods of twenty-four hours each can be marked off by the successive reappearances of certain surface features of our globe. The positions of the constellations can be used for a similar purpose. Occasionally comets are seen in all their glory. The planets appear regularly every night; but meteors are never seen. Yet meteoric particles, sometimes singly and sometimes in showers, frequently smite the face of the moon. They meet with no resisting atmosphere, to melt them by its heat or break the velocity of their descent. These particles, under their initial velocity and the moon’s attraction, crush into its surface with a force greater than that of a cannon ball striking a target. Kepler, though forced to abandon the theory after measuring the dimensions of some of the moon’s craters, at first thought that they were artificial excavations in which the inhabitants sheltered themselves during the long and scorching days. They would be no less necessary as a protection from this bombardment of meteoric particles than from the frightful extremes of heat and cold.