In its July 3, 1869 issue Harper’s Weekly presented a couple iconic images from the American independence movement during the 1770’s.

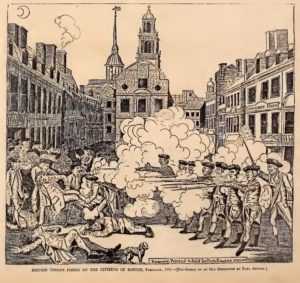

The incident Paul Revere depicted did not happen in 1775. The Boston Massacre “was a confrontation on March 5, 1770 in which British soldiers shot and killed several people while being harassed by a mob in Boston.” Although it got the date wrong, Harper’s Weekly refrained from calling the incident a massacre. The engraving seems to imply that a British commander gave the order to fire, but there was no evidence of that. Unlike Harper’s, Wikipedia doesn’t mention British soldiers killing a number of colonists before March 5th, but on February 22, 1770 a customs house employee did kill an eleven year old boy. Tensions increased between then and March 5th.

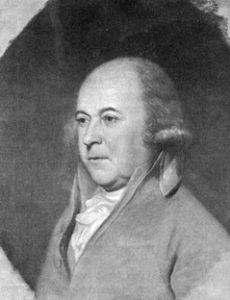

Later in the year eight British soldiers were tried in Boston for the murder of the citizens back in March. John Adams and Josiah Quincy II defended them. The jury only found two of the eight guilty – of manslaughter. They received greatly reduced sentences. The others were acquitted.

Wikipedia quoted John Adams on his role in the trial:

The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently. As the Evidence was, the Verdict of the Jury was exactly right. This however is no Reason why the Town should not call the Action of that Night a Massacre, nor is it any Argument in favour of the Governor or Minister, who caused them to be sent here. But it is the strongest Proofs of the Danger of Standing Armies.

— John Adams, on the third anniversary of the massacre

And indeed John Adams was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted (by twelve of thirteen colonies) 243 years ago today.

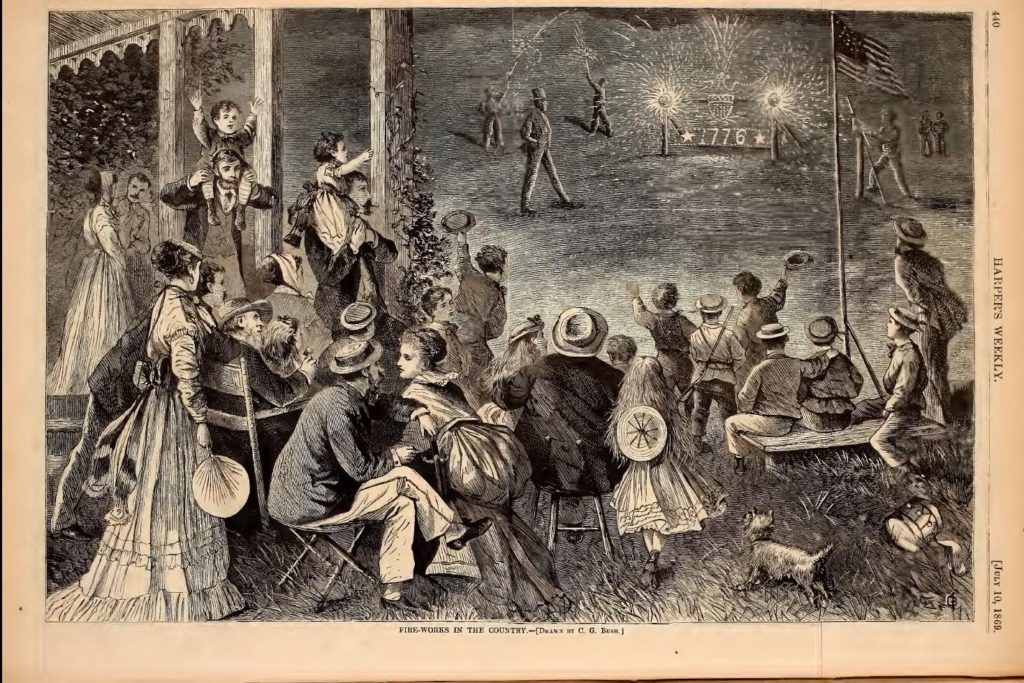

According to front pages from The New-York Times, that city didn’t officially celebrate Independence 150 years ago today. It was like Decoration Day. July 4, 1868 also fell on a Sunday. The paper’s July 5th edition noted that New York had filled up during the past 48 hours with visitors from the “neighboring country,” and it listed all the scheduled events for July 5th. In its July 6th issue the Times reported that the metropolis celebrated “with much less of the sound and fury” as was usual. There were few deaths. People seemed more reserved when they considered the sacrifices of the nation’s founders.

The images of Independence Hall and The Pennsylvania Gazette and the portrait of John Adams come from Signers of the Declaration, a National Park Service publication from 1973. You can find it at Project Gutenberg. The John Adams biography began:

Few men contributed more to U.S. Independence than John Adams, the “Atlas of American Independence” in the eyes of fellow signer Richard Stockton. A giant among the Founding Fathers, Adams was one of the coterie of leaders who generated the American Revolution, for which his prolific writings provided many of the politico-philosophical foundations. Not only did he help draft the Declaration, but he also steered it through the Continental Congress.

Fact checking for the history of the Declaration of Independence might have been pretty challenging. The National Parks Service publication explained the timing of some of the Declaration events:

On July 2, 1776 the Continental Congress voted for independence. For the remainder of July 2 and continuing until the 4th, Congress weighed and debated the content of the Declaration of Independence, which the drafting committee had submitted on June 28. Its author was young Thomas Jefferson, who had been in Congress about a year.

Congress altered the final draft considerably. Most of the changes consisted of refinements in phraseology. Two major passages, however, were deleted. The first, a censure of the people of Great Britain, seemed harsh and needless to most of the Delegates. The second, an impassioned condemnation of the slave trade, offended Southern planters as well as New England shippers, many of whom were as culpable as the British in the trade.

On July 4 all the Colonies except New York voted to adopt the Declaration. Congress ordered it printed and distributed to colonial officials, military units, and the press. John Hancock and Charles Thomson, President and Secretary of Congress respectively, were the only signers of this broadside copy. On July 8, outside the Pennsylvania State House, the document was first read to the public.

“Four days after obtaining New York’s approval of the Declaration on July 15, Congress ordered it engrossed on parchment for signature. At this time, indicative of unanimity, the title was changed from “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress Assembled” to “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America.”

Contrary to a widespread misconception, the 56 signers did not sign as a group and did not do so on July 4, 1776. The official event occurred on August 2, 1776, when 50 men probably took part. Later that year, five more apparently signed separately and one added his name in a subsequent year. Not until January 18, 1777, in the wake of Washington’s victories at Trenton and Princeton, did Congress, which had sought to protect the signers from British retaliation for as long as possible, authorize printing of the Declaration with all their names listed. At this time, Thomas McKean had not yet penned his name.

The publication’s forward was written by Richard M. Nixon, the United States president in 1973 :

“As we approach the two hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, each of us is stirred by the memory of those who framed the future of our country.”

“In the coming years we will have many opportunities to refresh our understanding of what America means, but none can mean more than personal visits to the sites where freedom was forged and our founding fathers actually made the decisions which have stood the severest tests of time.”

“I remember my reactions, for example, when I visited Independence Hall in Philadelphia in 1972 to sign the new revenue sharing legislation. Walking into the building where that small group of patriots gathered some two centuries ago, I thought back to what it must have been like when the giants of our American heritage solemnly committed themselves and their children to liberty. The dilemmas they faced, the uncertainties they felt, the ideals they cherished—all seemed more alive to me than ever before, and I came away with an even stronger appreciation for their courage and their vision.”

“As people from all over the world visit the places described in this valuable book, they, too, will feel the excitement of history and relive in their minds the beginnings of a great Nation.”

“I commend this book to your attention and encourage all people, Americans and foreigners alike, to make a special effort to visit our historic sites during these Bicentennial years.”

“The White House

Washington, D.C.

(signature)

Richard Nixon”

I’m pretty sure President Nixon faced uncertainties and dilemmas in 1973; he wouldn’t be president in the Bicentennial year.

The NPS book included the engraving of March 5, 1770 that Harper’s Weekly used in 1869: “The Revolutionaries utilized this exaggerated version of the Boston Massacre (1770) by Paul Revere to nourish resentment of British troops.

All the Harper’s Weekly material from 1869 can be found at the Internet Archive. From the Library of Congress – the engraving, “A sensationalized portrayal of the skirmish, later to become known as the “Boston Massacre,” between British soldiers and citizens of Boston on March 5, 1770.” According to Wikipedia, “This famous depiction of the event was engraved by Paul Revere (copied from an engraving by Henry Pelham), colored by Christian Remick, and printed by Benjamin Edes”; Boston Commons monument

I added more information from Robert Middlekauff’s book on July 8, 2019.

July 9, 2019: I learned about the medial S at onlinewritingjobs; in A World on Fire Amanda Foreman writes about and pictures Charles Francis Adams and his sons Charles Jr. and Henry. “Though [Charles Sr.] was dutiful, honest, and hardworking, his family legacy cast a shadow over his entire life. ‘Charles Francis Adams naturally looked on all British [statesmen] as enemies,’ wrote Henry Adams.”[1]

July 5, 2019: Any possible blue-gray connection? Well, not only was John Adams’ son John Quincy Adams the sixth United States president, he “became an important antislavery voice in the Congress” from 1831 until his death in 1848. John Q.’s son Charles Francis Adams Sr. served as United states minister to Britain from 1861-1868 and ran as the vice-presidential candidate on the Free Soil ticket in 1848. His son Charles Francis Adams Jr. served in a couple Massachusetts cavalry regiments from December 1861 until the end of the Civil War. His brother Henry was Charles Sr.’s personal secretary in London.

Front pages from The New-York Times during the first week in July were silent about Independence Day (although Jack Dempsey did win the World Heavyweight championship on the 4th by defeating Jess Willard in three rounds in Toledo, Ohio.) New Yorkers were gazing up in the sky again. And the British really were coming. The R34 was a dirigible and “became the first aircraft to make an east to west transatlantic flight in July 1919 and, with the return flight made the first two-way crossing.” One American, representing the U.S. Navy, was aboard.

__________________________________________

____________________________

Back to the massacre. According to Robert Middlekauff, what happened on March 5, 1770 “does not seem to have been the result of a plot or plan on either side, but rather the consequence of deep hatreds and bad luck. The hatreds brought out roving bands of civilians and soldiers, all apparently in search of one another.” When British Captain Preston decided he had to rescue Private White, who was guarding the customshouse, he marched with six privates and a corporal to the confrontation. The crowd filled in behind the British detachment and surrounded it. Mr. Middlekauff wrote that Captain Preston made two understandable mistakes: “He did not immediately order the guard to march back up the street with White; instead he shifted its alignment from a column of twos to a single line, a rough semi-circle, facing out from the customshouse. And he ordered his men to load their muskets.”[2]

- [1]Foreman, Amanda A World on Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War. New York: Random House, 2010. Print. photos between pages 178 and 179.↩

- [2]Middlekauff, Robert The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution 1763-1789. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982. Print. pages 203-205.↩