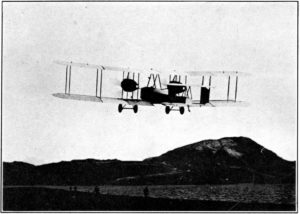

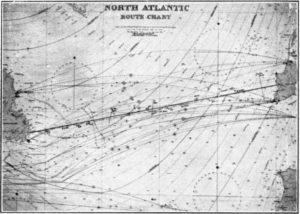

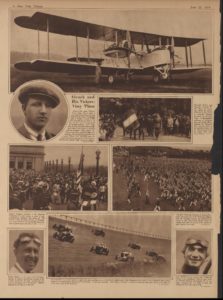

World War I was disruptive, and while it was a boon to aviation, it caused the postponement of an aerial competition. In 1913 the Daily Mail offered a prize of £10,000 to “the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours.” The contest was back on after the Armistice was signed. There were at least a couple serious attempts in May 1919, but the prize wasn’t won until the next month. Between June 14 and June 15, 1919 two British citizens, John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown, successfully made the first non-stop transatlantic flight by flying from Newfoundland to Ireland in about sixteen hours.

Wikipedia describes the crossing:

It was not an easy flight. The overloaded aircraft had difficulty taking off the rough field and only barely missed the tops of the trees. At 17:20 the wind-driven electrical generator failed, depriving them of radio contact, their intercom and heating. An exhaust pipe burst shortly afterwards, causing a frightening noise which made conversation impossible without the failed intercom.

At 5.00 p.m., they had to fly through thick fog. This was serious because it prevented Brown from being able to navigate using his sextant. Blind flying in fog or cloud should only be undertaken with gyroscopic instruments, which they did not have. Alcock twice lost control of the aircraft and nearly hit the sea after a spiral dive. He also had to deal with a broken trim control that made the plane become very nose-heavy as fuel was consumed.

At 12:15 a.m., Brown got a glimpse of the stars and could use his sextant, and found that they were on course.Their electric heating suits had failed, making them very cold in the open cockpit.

Then at 3:00am they flew into a large snowstorm. They were drenched by rain, their instruments iced up, and the plane was in danger of icing and becoming unflyable.The carburettors also iced up; it has been said that Brown had to climb out onto the wings to clear the engines, although he made no mention of that.

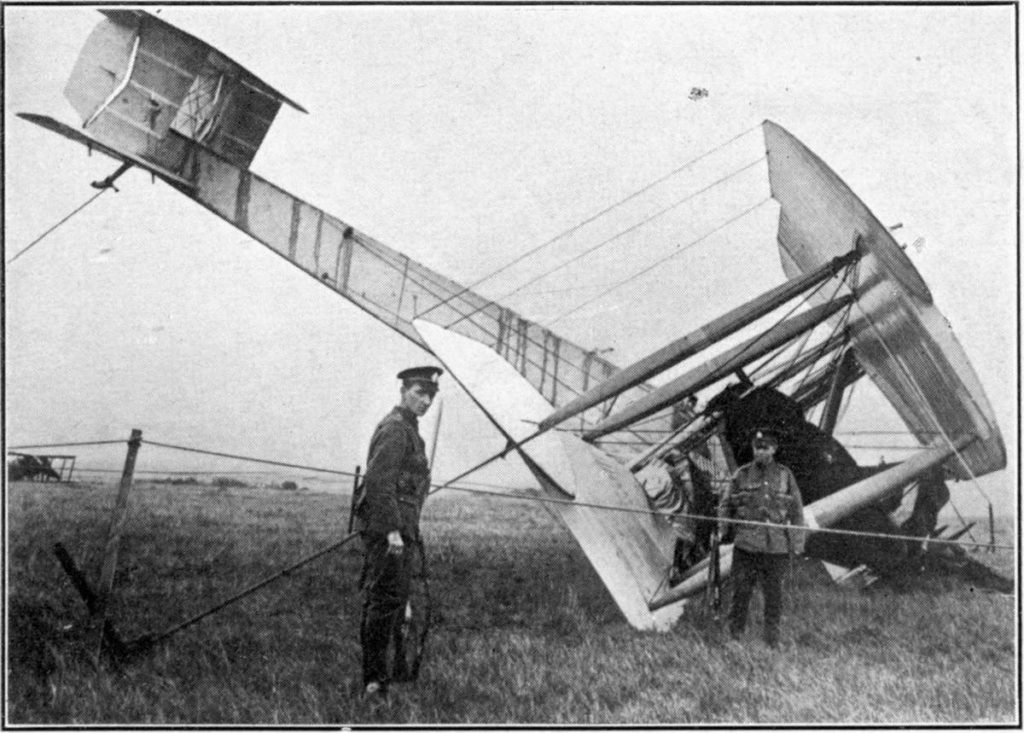

They made landfall in County Galway, crash-landing at 8:40 a.m. on 15 June 1919, not far from their intended landing place, after less than sixteen hours’ flying time. The aircraft was damaged upon arrival because of an attempt to land on what appeared from the air to be a suitable green field, but which turned out to be Derrygilmlagh Bog, near Clifden in County Galway in Ireland …

The aviators were not hurt in the crash. However, John Alcock was killed on December 18, 1919 when the new Vickers amphibious aircraft he was piloting crashed in a fog. He was headed to Paris for an aeronautical exhibition. In his 1920 book Flying the Atlantic in Sixteen Hours (at Project Gutenberg) Sir Arthur Whitten Brown described the prize-winning flight, discussed the navigation of aircraft, and analyzed the possibilities of commercial transatlantic aviation. After the transatlantic flight and initial celebratory activities the aviators needed a good night sleep. Sir Whitten Brown described a phenomenon that is certainly still a part of air travel. Nowadays people call it jet lag:

The wayside gatherings seemed especially unreal—almost as if they had been scenes on the film. By some extraordinary method of news transmission the report of our arrival had spread all over the district, and in many districts between Clifden and Galway curious crowds had gathered. Near Galway we were stopped by another automobile, in which was Major Mays of the Royal Aëro Club, whose duty it was to examine the seals on the Vickers-Vimy, thus making sure that we had not landed in Ireland in a machine other than that in which we left Newfoundland. A reception had been prepared at Galway; but our hosts, realizing how tired we must be, considerately made it a short and informal affair. Afterwards we slept—for the first time in over forty hours.

Alcock and I awoke to find ourselves in a wonderland of seeming unreality—the product of violent change from utter isolation during the long flight to unexpected contact with crowds of people interested in us.

To begin with, getting up in the morning, after a satisfactory sleep of nine hours, was strange. In our eastward flight of two thousand miles we had overtaken time, in less than the period between one sunset and another, to the extent of three and a half hours. Our physical systems having accustomed themselves to habits regulated by the clocks of Newfoundland, we were reluctant to rise at 7 A. M.; for subconsciousness suggested that it was but 3:30 A. M.

This difficulty of adjustment to the sudden change in time lasted for several days. Probably it will be experienced by all passengers traveling on the rapid trans-ocean air services of the future—those who complete a westward journey becoming early risers without effort, those who land after an eastward flight becoming unconsciously lazy in the mornings, until the jolting effect of the dislocation wears off, and habit has accustomed itself to the new conditions.